Warren, E. (2005). Young Children's Ability to Generalise the Pattern

advertisement

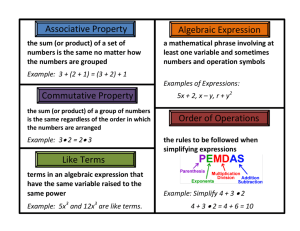

Year 6 and 7 Algebra and Patterns Challenges Solutions / Strategies Justification and Origin Transitioning from concrete patterning to viewing patterns as functions (Warren, 2005). Origin: Often attributed to reasons such as students having never developed the conceptual understanding of the target mathematics concept/skill. http://www.coedu.usf.edu/main/departments/sped/mathvids/in dex.html Conceptual understandings of a target mathematics concept/skill is demonstrated by “the ability to recognize functional relationships between known and unknown, independent and dependent variables, and to discern between and interpret different representations of the algebraic concepts. It is exemplified by competency in reading, writing, and manipulating both number symbols and algebraic symbols used in formulas, expressions, equations, and inequalities.” http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.cqu.edu.au/ehost/detail ?sid=8d7c9040-f325-4cf0-a054ba8446eedede%40sessionmgr112&vid=2&hid=122&bdata=J nNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=ehh&AN=6186365 3&anchor=AN0061863653-4 Identifying and articulating the missing steps in an incomplete pattern. For example the LM may provide students with steps 1, 2 and 5. Students are often unable to identify steps 3 and 4 (Choi, Huh, LaRue, 2010). In this instance, gestures and manipulation of materials add to the conversations, elements that are missing from written responses. http://emis.kaist.ac.kr/proceedings/PME29/PME29RRPape rs/PME29Vol4Warren.pdf Origin: LMs focus too heavily on growing patterns that are consecutive rather than using patterns that require students to find missing steps. Is it possible to put in prediction and guessing into this??? As in they have to predict the 3rd step and could even work out the 4th step from a guess and check strategy. The use of concrete materials appeared to assist many children ascertain the missing steps in the pattern. A number, when completing the accompanying pen and paper worksheet, recreated the pictorial pattern with the tiles and then used the https://eee.uci.edu/wiki/index.php?title=Patterns_and_Alge braic_Thinking&redirect=no tiles to create the 5th and 10th step. They then drew a picture of their solution on the worksheet. Many children exhibited an ability to express the generalisations orally, but such descriptions often lacked precision. http://emis.kaist.ac.kr/proceedings/PME29/PME29RRPapers/PM E29Vol4Warren.pdf Fluency in the language of algebra demonstrated by confident use of its vocabulary and meanings as well as flexible operation upon its grammar rules (i.e. mathematical properties and conventions) are also indicative of conceptual understanding in algebra. http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.cqu.edu.au/ehost/detail?si d=8d7c9040-f325-4cf0-a054ba8446eedede%40sessionmgr112&vid=2&hid=122&bdata= JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=ehh&AN=6186 3653&anchor=AN0061863653-4 Converting a visual pattern to a table of values so as to identify relationships from within the table (Choi, Huh, LaRue, 2010). Origin: Concrete to abstract Why is it important to be able to go from concrete to abstract? Links to the curriculum? Links to real life situations??? Patterns where the relationship between the pattern and position were explicit. These types of patterns appeared to assist children to verbally describe the relationship between the pattern and the position, for example, it is twice the step number, it is the same as the step number, it is one more than the step number. http://emis.kaist.ac.kr/proceedings/PME29/PME29RRPaper s/PME29Vol4Warren.pdf Explicit questioning to link the position to the pattern- These questions were of the form – What does the pattern look like? How many rows? How many in each row? For the 3rd step, how many on the bottom, how many on the top? The questions explicitly related the position to the pattern’s visual components. Generalising from the pattern in small position numbers, to large position numbers- It was found that to articulate the relationship between position number and the visual pattern in general terms, children needed to discuss the relationship for increasingly larger positions. http://emis.kaist.ac.kr/proceedings/PME29/PME29RRPaper s/PME29Vol4Warren.pdf Students creating their own patterns (Choi, Huh, LaRue, 2010). Understanding of the equals sign and how it is representative of quantitative sameness (Vance, 1998). using concrete materials to create patterns, specific questioning to make explicit the relationship between the pattern and its position, and specific questioning that assist children to reach generalization with regard to unknown positions. http://emis.kaist.ac.kr/proceedings/PME29/PME29RRPape rs/PME29Vol4Warren.pdf To reinforce the concept that a number can be represented by many different expressions, learners are asked to name a given number in several different ways using two or more numbers and one or more operations. For example, 9 can be named as 4 + 3 + 2 or 2 x 5 - 1. In a related activity, equations are to be completed so that an expression has at least one operation on each side of the equals sign. For example, given 7 + 5 as one side of an equation, a student might write 7 + 5 = 2 X 6 or 7 + 5 = 10 + 5 – 3 (Vance, 1998). http://www.learner.org/courses/learningmath/algebr a/pdfs/AlgPerspective.pdf Origin: Students too often complete LM provided pattern rather than creating their own (Choi, Huh, LaRue, 2010). Individual Mastery is important Origin: This misconception is reinforced early on when they are shown the vertical computational format for 3 + 2; the bar under the lower number is a signal to find an answer. It is also true that pressing 3 + 2 = on a calculator results in the standard form of the number. Therefore, children need experiences in which they see and write other types of number sentences, such as 5 = 3 + 2 and 3 + 2 = 4 + 1 (Vance, 1998). Practical example is using a scale or see saw and showing that the equal sign is an expression of two sides??? Variances in the standard number sentence of a + b = c (Choi, Huh & LaRue, 2010). Bracket usage as a static signal telling students which operation to perform first in an algebraic equation (Gallardo, 1995). Origin: Students who are used to seeing number sentences in the form a + b = c do not see 9 = 3 + 6 as a "proper number sentence" (Choi, Huh & LaRue, 2010). Origin: Students tend to solve such expressions based on how the items are listed, in a left-to-right fashion (in the case of English speaking students), consistent with their cultural tradition of reading and writing. Therefore, the rules underlying the order of operations can actually contradict students’ natural ways of thinking. http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.cqu.edu.au/eds/detail?vid=6& hid=120&sid=56658b62-ac31-4c51-97e32878f9a574e3%40sessionmgr104&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpd mUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#db=ehh&AN=73959391 (CHECK) INCLUDE ICT References Choi, S. Huh, L., & LaRue, C. (2010). Patterns and Algebraic Thinking. Retrieved April 2, 2012, from https://eee.uci.edu/wiki/index.php?title=Patterns_and_Algebraic_Thinking&redirect=no Vance, J. H. (1995). Number operations from an algebraic perspective. Teaching Children Mathematics, 4(5), 282. Warren, E. (2005). Young Children's Ability to Generalise the Pattern Rule for Growing Patterns. Paper presented at the 29th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED496965.pdf Gallardo, A. (1995). Negative Numbers in the Teaching of Arithmetic. Repercussions in Elementary Algebra. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the North American Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED389549.pdf Tessa’s Notes: Maybe have examples of each challenge?