Goodness Knows the Wickeds' Lives Are Lonely

advertisement

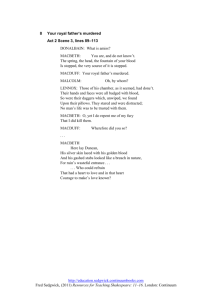

Goodness Knows the Wickeds’ Lives Are Lonely… Feraco Search for Human Potential 6 December 2011 Genuine Witch Chants* Macbeth’s fourth act begins with the material that earned it a long ban from its target audience – some “genuine” witch chants as the Weïrd Sisters mix up the potion for their charm. The “Double, double” sequence is probably Macbeth’s most widelyrecognized, but for mostly shallow reasons (apparently, it’s fun to sing rhymes while dancing around a cauldron). By this point, you’ve seen Shakespeare slide extra meaning in around Macbeth’s edges to recognize that the “Fair is foul” doubling motif appears again in the chants. Unsettling Imagery There’s also some very specific, unsettling imagery here: most of what’s being tossed in the pot is either swollen with venom, representative of sin (pieces of blasphemers, things claimed under cover of darkness or eclipse, etc.), or dismembered parts of babies (the owlet’s wing and the finger of a child who was born in a ditch and subsequently strangled – how is unclear). I point out the specificity of what seems like babble because, as you can clearly see, the witches are mixing things that pertain to Macbeth himself Everything from shattered newborns to darkness and poison (the guard’s drinks, trust as venom, etc.) reflects him somehow. Knowledge – Understanding = ? But the Sisters can’t finish before Macbeth arrives. When he asks them what they’re doing, they reply – in perfect unison – that their deed has no name. (Here, the thing to notice is not merely that Macbeth himself has committed foul, nameless deeds, but that the three respond to him in unison; we’ll study this in far greater detail later.) And what follows, of course, must happen: Macbeth has not learned the lesson Banquo’s fatal mistake should have taught him, which is that one should be careful when demanding – wishing for – something. He demands knowledge that is not rightfully his, seeking to gain advantage over a future that’s much larger and more complicated than he can understand. What he gets is knowledge, but it’s paired with some truly fatal, bloody misconceptions: Siddhartha taught us that wisdom only comes from experience and understanding, not from blindly following or trusting in the words of others, and that lesson’s rarely more applicable than it is here. The Armed Head With the addition of a filicidal sow’s blood (shades of Lady Macbeth’s “baby-dashing” line here) and the sweat and grease that fell from hanged murderer’s foreheads, an “Armed Head” rises from the cauldron. “Armed” should not be taken literally here, at least not in its primary sense: Shakespeare is describing a head clad in a helmet or armor. It tells Macbeth exactly what he expects to hear: that he must beware Macduff, the Thane of Fife. One should notice that the king, far from his throne, is powerless during the encounter: he is told to keep silent, as the apparition can sense his thoughts, and it ignores his request for more knowledge (as the first Sister bluntly tells him, the Head “will not be commanded”). The Blood-Covered Child And unfortunately for Macbeth, this powerlessness isn’t a sufficient warning to be on guard against arrogance (i.e., an unwarranted belief in one’s power or superiority). He hasn’t struck us as a particularly proud person before – Lady Macbeth’s interactions with him seem to have guaranteed that – but his hubris (selfdestructive arrogance) gets the better of him here. No sooner does the Head finish its spiel than a child, covered with blood (a chilling image), rises in its place. When it tells him to be “bloody, bold, and resolute,” it’s not just repeating SFHP advice. It’s telling Macbeth that he can act decisively, for “none of woman born” (no one born “naturally”) can hurt him. Macbeth, of course, takes this to mean that he can safely disregard the Head’s warnings – for isn’t Macduff, like all men, “of woman born”? (Actually…) Just to be safe, however, Macbeth decides to have him killed anyway; at that point, he believes, he’ll be so secure that he’ll be able to “sleep through thunder.” Hubris and Trust Shakespeare does something interesting with his security examination here. It’s trust in others that destroys Duncan and, to a lesser extent, Banquo. But their downfalls also stem from something else. The man who’s most vulnerable to a threat is the one who believes he can’t possibly be harmed by it. Duncan foolishly believes that he’s safe, that, with the revolt crushed and his guards at the ready, no one can hurt him. (After all, isn’t he king?) Banquo fails to consider that Macbeth could want to kill him, even though he’s already killed thanks to the prophecy – and it’s not like Macbeth wasn’t listening when Banquo heard his own prophecy. But he, too, believes he’s untouchable, at least by his best friend. So Duncan lets his guards drink at the home of the replacement from his corrupted advisor, and Banquo rides by torchlight with the figure Macbeth would most want destroyed. Anything for… Both actions reek of hubris – the choices of men who foolishly believe that bad things aren’t going to happen to them, even though Shakespeare has shown us plenty of reasons for both men to have their guards up. It’s that very same mistake – nothing bad can happen to me! – that Macbeth makes here. By hearing that “none of woman born can harm him,” he makes a leap (particularly later in the play) to “I can’t be harmed.” This simply isn’t true. On some level, he must know this; otherwise, there’s literally no reason to kill Macduff. But Macbeth’s so desperate for comfort – the real reason he’s sought out the witches, for there’s obviously security in certainty – that he’ll happily make that leap. Anything for the possibility of sleeping again, of feeling human again. The Child, the Crown, and the Tree Then – just as he’s started to virtually cackle with glee over the nearness of his victory – a child wearing a crown rises from the cauldron. It is perhaps the single most powerful image one could show Macbeth, so he pays attention. The child holds a tree for some reason…an important reason, as it so happens: it tells him that he cannot be beaten until Birnam Wood (a forest) marches against him at Dunsinane (the location of Duncan’s/Macbeth’s castle). Somewhat justifiably, Macbeth is a bit perplexed by the prophecy (walking trees??), even as it cements his newfound feelings of certainty: if the only one who can defeat me is someone who isn’t “of woman born,” and they can only beat me after a bunch of trees start walking toward my castle, aren’t you just telling me I can’t lose? Seek to Learn No More Yet Macbeth, flush with triumph, must know more still. There’s one point the three apparitions didn’t mention: what will happen with Banquo’s line. The witches warn him, unambiguously: Seek to learn no more. And Macbeth, equally unambiguously, replies: I will be satisfied. That’s a demand, not a statement of satisfaction. He threatens to curse the witches, which is not only incredibly foolhardy – these are the people you plan to antagonize? – but also uncomfortably reminiscent of Banquo’s words to them as he finishes his demands “[I] neither beg nor fear your favours nor your hate” – he should have The cauldron immediately sinks, and as the air fills with trumpeters heralding something, the Sisters say (in unison): Show his eyes, and grieve his heart; come like shadows, so depart. When the ____ Come Marching In Eight kings appear, with the eighth holding a mirror. They’re clearly not related to Macbeth, who flies into a rage, screaming at each of the kings who walks past him, then at the witches, before the eighth king reaches him and shows him an even more terrible sight in the depths of its mirror: a seemingly endless line that follows the eight in front of him, with some of the new ones wearing crowns signifying the unification of two kingdoms. All the while, the bloodied ghost of Banquo smiles at Macbeth from the back of the line of eight kings, pointing at them silently: They’re mine. Satisfied? And as Macbeth gapes, disbelievingly, at the apparitions, his worst nightmare given almost fleshy form, one witch asks him why he looks surprised. Didn’t he always know this was so? Didn’t he always know this would be his fate? Have the Sisters ever lied? Have they ever been wrong? The Sisters dance, laughingly, telling Macbeth that he can now say they gave him what he came for. Then they disappear, never to return. A Wounded Animal Lennox arrives to tell him of Macduff’s departure (previously mentioned in Act III, Scene VI), and in his new state of disequilibrium, Macbeth lapses into a truly sick soliloquy: he resolves to arrange an invasion for Macduff’s castle in Fife and have everyone inside it murdered, including his wife and children. Macbeth, like any wounded animal, is now more dangerous than he would otherwise be, simultaneously convinced that he can’t lose and terrified that his defeat is inevitable. The only course of action for him, then, is to eliminate every threat he faces, one by one. While Lady Macbeth is busy wrestling with her guilt, Macbeth has resolved to murder his opponents until there’s no one left to kill; they’ve essentially swapped moral compasses, and their needles are spinning too wildly to save either one of them. Picking Off the Weakest Ones The terrible thing, however, is that Macbeth keeps killing people a) by proxy, b) attacking victims when they’re at their most vulnerable (he’s always had an eye for an opponent’s soft spot, just as Lady Macbeth does: Macdonwald’s unzipping starts and ends at his softest points), and c) picking people who don’t know he’s coming for them. Fleance survived either by chance or by fate, but no one else is that lucky. The people he kills aren’t even the ones who truly threaten him (Malcolm, Macduff, perhaps Fleance). They’re people related to those threats, and their deaths – if we’re being realistic – only serve to harden their opposition to Macbeth. Never an Accident Notice, however, that these “misdirected” killings aren’t accidental. Macbeth knows full well that Macduff isn’t in his castle. The only thing he can accomplish is the slaughter of Macduff’s family – notably, a group of people that poses no threat to him, has never been predicted to pose a threat to him, and does not stand in the way of his ambitions. One could argue that Macbeth has only killed at this point because he “must”: Duncan’s death represented the fulfillment of prophecy, whereas Banquo’s killing was an attempt to thwart it. These latest murders would be voluntary, unprovoked, unnecessary. Macbeth sends his murderers anyway. Th’ Primrose Way And in one of those “dramatic irony” sequences that Shakespeare revels in – the audience knows what’s coming, but the characters don’t – we’re introduced to Lady Macduff as she’s bemoaning her husband’s decision to leave for England. Macbeth listened to his wife; Macduff overruled his. By departing, he’s left his castle – and his family – defenseless. The Porter’s line about admitting those whose choices lead them to Hell takes on terrible significance here. Wrens and an Emptied Nest Lady Macduff isn’t stupid: she knows why Macduff has gone. But she also recognizes that Macduff’s made enemies, powerful ones, and she rightly fears for her safety. In a tragic parallel to Lady Macbeth’s words, she questions what kind of man her husband is – not due to his capacity (or lack thereof) for murder, but for “wanting the natural touch” (lacking the natural instincts that should drive every parent). Where are his priorities? she wonders. “The poor wren, the most diminutive of birds, will fight, her young ones in her nest, against the owl.” All is the fear and nothing is the love. In our time of need, our man has left us alone. For Your Consideration Both Lady Macbeth and Lady Macduff demand that their husbands make decisions that not only take them and their needs into consideration, but prioritize them – that the needs of family outweigh all other demands. Macbeth, for better or worse, comes to see his primary responsibilities as a) his own needs and b) his wife’s needs. Macduff doesn’t, and he will pay a terrible price. Left for Dead Ross tells Lady Macduff to be patient – that the times they live in are dangerous indeed, but their unpredictability has caused her husband to choose his current course. Macduff is doing what he does for the greater good; nothing would make him happier than simply staying at home by their side, with the people he’s most personally devoted to, but others need him to do more. Macduff’s wife will have none of it; she tells her son that his father’s forsaken them, and that his father is therefore dead. Funny Games Shakespeare then lets the son and mother engage in an odd, witty repartee, and it’s a truly sick scene: we know they’re about to be cut down like animals in their own home, and they’re sitting there joking with each other. We can’t laugh at anything they’re saying because we’re bracing for the inevitable, as unable to control the events we’re watching as Macbeth is to control what the prophecies spelled out. We’re suddenly aware of how the characters, on so many different levels, feel: helpless and out of control, with our dread of what we know amplifying our fears. Stabbing Sons And as the son makes his last joke – that if the “liars and swearers” are to be killed by the honest men, they’re idiots, for there are far more liars than honest men – a messenger arrives, frantically urges her to run far away with her children, and flees. Before she can react, the murderers arrive, and – in one of the most jarring moments Shakespeare’s ever put on stage – stab her son to death in front of her. The boy pleads with his last breath for his mother to flee – a reversal of Banquo’s death (where the parent tries to spare the child), and a futile attempt, as the murderers chase his mother offstage and cut her down there. One Fell Swoop The earlier killings in Macbeth either happened offstage or under deep cover of darkness. With the death of Macduff’s family, Shakespeare’s shoving the ugliness of murder directly in the audience’s faces. This isn’t entertainment: it’s butchery, loud and messy and close. Don’t underestimate how horrible this crime is. It’s not just the murder of an innocent family. Macbeth, of all people, should understand what he’s doing to Macduff: he’s annihilating his entire line. The term “one fell swoop” comes from Macduff’s reaction to the news that Macbeth’s attacked his castle (“fell” means foul, vile, wicked, tainted, or evil): with one stroke, Macbeth has killed “all [his] pretty ones,” the very people he should have protected, the people who made his life meaningful. He may still be alive, but Macbeth, in his cowardice, has gone behind his back and robbed him of all that once made him whole. Vacuum I’ve mentioned the role isolation plays in the play, and how terrible people feel – and how terribly they act and decide – when they’re alone. Yes, it’s true that we only get a sense of who Macbeth “really” is when he’s in soliloquy mode. But how lonely is that existence? To have absolutely nobody who truly understands you? Nobody who you truly understand? Nature abhors a vacuum, and involuntary isolation is a roaring vacuum for the soul Human beings will often go to desperate lengths to fill that vacuum. The Unholy Trinity I asked you to notice that Shakespeare unifies the witches, giving them the very power Macbeth lacks: the power of numbers, the support of multiplicity. Entire schools of religious thought center themselves around polytheism – a god for every cause. Even the monotheistic Christianity attests to the power of the Holy Trinity. Societies, families, relationships – all stem from the fundamental belief in power and improvement via company. So while a single witch can be a memorable character in a play – we’ve seen soothsayers and oracles sharing prophecies since the Greek plays hit the stage – we remember Shakespeare’s bizarre, disfigured Unholy Trinity because their impact on us does uneasy things to our psyches. Beyond All Limits For it’s not simply that the witches seem to know the future, but that they seem somehow more than human – not better, yet still more powerful, transcending our limitations. In their numbers, their synchronicity of purpose and word, this nameless pack of cackling hags seems representative of something so powerful as to be alien to us, impossible to understand. They are recognizable – women? – and yet not. It’s almost as though our minds, being baffled by their true nature, perceives them in a way that kind of makes sense – like trying to capture a concept like Fate or God with a three-or-fourletter word – but ultimately fails to represent them. We can’t fully understand them, and when we try – especially when we try to make them serve us – the attempt leaves us feeling powerless, grasping onto anything we can to feel some control. The Butcher Contrast this with Macbeth, who’s either killing off his friends or fighting with his wife, the holder of a barren scepter and an empty line, under threat from the sons of both his victims – in other words, impossibly, irreversibly alone. It is the power of numbers that threatens him, the lone, solitary figure screaming impotently as the specter of Banquo’s endless line marches before him, dooming him and his family with every silent, solemn step. It is the power of numbers that threatens him, as Malcolm’s and Siward’s soldiers begin overwhelming his defenses in Act V. And it is the power of numbers that threatens him, in the form of the dangers he provokes through his crimes. There are too many threats to combat, and while he knows they’re out there, he doesn’t really see them – just as the numberless, now-invisible stars above him quietly and dispassionately spin his fate. Salvation, Invasion So Macbeth, true to form, reacts desperately when facing the possibility of lost control. He kills Macduff’s entire family in one fell swoop. He’s sowing the seeds of his own destruction, but he’s taking a whole bunch of people with him. And in the meantime, Scotland is falling apart: a nation that began the play fending off a foreign invasion now finds itself praying for one in order to find some degree of salvation. The Cipher That’s predicated, however, on the alternative to Macbeth being an improvement on the current ruler. It’s not until the final scene of Act Four, however, that we realize we’ve been baited into the same “trust mistake” yet again. We automatically believed that Duncan was a good king, ignoring the fact that the play begins with him beating back a revolution. Now we assume that his oldest son, Malcolm, is a better option than Macbeth, because…why, exactly? Because he didn’t kill his way to the throne, which would have involved murdering his father? We know virtually nothing about him, save that he’s Duncan’s son. We haven’t seen him do anything that marks him as worthy of the throne. We’ve barely seen him more than Fleance, who’s being intentionally sidelined; the only thing we can really remember him doing is running away after Duncan’s been murdered. He’s a cipher. A Hollywood Ending, Part I Yet when we hear that Macduff’s gone out to meet him, we expect the scene to play out in a familiar way. Macduff will meet the noble prince and his new ally, Siward; together, they’ll lead an army against Macbeth, conquering and taking back what’s rightfully theirs. The wise and gentle Malcolm will be placed on the throne, as he should have been following his father’s death. Donalbain will come home. Peace and harmony will be restored to the land. It’s all very simple, really. On Guard, En Garde Except that’s not what we get at all. Instead, Macduff meets a young man who’s very frightened and deeply suspicious of others, almost to a paranoid degree. He subjects Macduff to not one but two tests, both involving naked deception. In the first, he tries to bait Macduff into “selling him out” – betraying him to Macbeth, to whom Macduff is supposedly secretly loyal. He, too, questions why Macduff would leave his family so alone, and would do so in such an abrupt fashion. And even as he’s back-pedaling from that – Oh, don’t mind what I say, I’m just suspicious of others after my father’s death – he quickly pivots to a disturbing self-portrayal, excoriating himself for his sinfulness and venality. Corruption If I were to be king, he continues, Scotland would burn: “Black Macbeth will seem as pure as snow” by comparison. If there’s an appetite or weakness in the book, Malcolm lays claim to it. Avarice? Check. Unbridled sexual appetite? Check. A lust for power? Check. A willingness to murder rivals? Check. Plotting to take the nobles’ lands after murdering them? Check. A complete and utter lack of any redeeming virtues? Malcolm swears that nothing about him can be redeemed. He is without respect for justice, devotion, patience, or courage. Escalation As he goes down the list, Macduff desperately tries to tell him that he’s being too hard on himself, or that the sin he describes is understandable (or less dire than he believes). But with each protestation, Malcolm worsens his self-criticism. There’s a clear pattern of escalation on his part, and he goes on and on until finally Macduff throws up his hands, weeping for his helpless nation – now doomed to suffer under a tyrant’s rule, whether or not Macbeth occupies the throne – and verbally tears into Malcolm with a fury we’ve never seen him display before. Your father was a good, gentle king; your mother was a devout, caring woman. That they could have produced something as wicked as you just proves that God has forsaken my country, and thus I must forsake it too. Reversal And as Macduff turns from him, angry and despairing, Malcolm suddenly “breaks character” and shows his true face. It was all a test! He just wanted to test Macduff’s loyalty to Scotland. If he had stayed steadfastly loyal to Malcolm in the face of all those terrible confessions, it would have been evidence that Macduff could be tempted to do terrible things. Someone who mourns for their country, on the other hand, must be loyal to it. It’s a complete reversal of character, and it’s incredibly jarring when experienced live. Deceptive Shapeshifting Things Following Malcolm’s monologue – during which he professes to be all of the things we’d want a king to be – Macduff points out that “such welcome and unwelcome things at once [are] hard to reconcile.” And if they’re difficult for Macduff to process, how are we supposed to feel? This is our first real exposure to Malcolm, and it tastes sour: this is the new king? This is the vessel into which the Scottish people should place their hopes? This deceptive, shapeshifting thing? The Pressure and the Damage Done When Ross shows up to deliver the news of Macbeth’s attack on Fife, Macduff can join forces with Malcolm without any qualms: uncertainty’s easy to banish in the face of searing rage. Malcolm even compliments him on how “manly” his expressed desire for vengeance sounds. (There’s the masculinity issue again…) And to his credit, Malcolm doesn’t do or say anything negative for the rest of the play. But the damage, as Susan Snyder points out, has already been done: Malcolm’s left such a negative first impression that it proves impossible to shake entirely. Mysterious Sisters Act Four ends with seemingly all of the pieces arranged as they should be: Malcolm and Macduff have united in order to gain revenge, Macbeth is actively seeking to cement his power, and a clash seems imminent. Fleance is off wandering around somewhere, and we still don’t understand why the Sisters do what they do – do they have a choice? Are they mouthpieces of fate? Hecate’s presence indicates a plan, but the plan’s motivations are too murky to make out. Nothing Sacred, Nothing Pure No matter. The audience has spent four acts waiting for the inevitable clash between good and evil, and now it looks like we’ll get it. We want Macbeth to pay for what he’s done. We want Macduff, Malcolm, or Fleance to seek some sort of retribution for the people that they’ve lost. But Shakespeare’s damaged his “good” characters – Malcolm’s “fake” sinfulness, Macduff’s “abandonment” of his family – and worsened his “bad” ones. Can there be any winners here? Fair is foul…