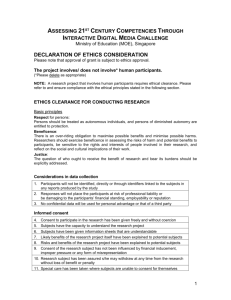

Ethics & Law - Michigan Association of School Psychologists

advertisement

Ethics & Law MASP Fall Conference, 2014 Cheryl L. Somers, Ph.D. See last page for references Unless otherwise noted, most information was taken from Jacob, S., Decker, D. M., & Hartshorne, T. (2010). Ethics & law for school psychologists (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. I. Definition of Terms Ethics = “a combination of broad ethical principles and rules the guide the conduct of a practitioner in his or her professional interactions with others.” Law = “a body of rules of conduct prescribed by the state that has binding legal force.” Both APA and NASP ethics require that we know and respect the law. II. Questions to Ask Oneself: Do I understand my legal obligations correctly? What actions does the law specifically require or prohibit (must do, can’t do)? What actions does the law permit (can do)? Even if an action is legal, is it ethical? Do I understand my ethical obligations correctly? III. Ethics A. Review of APA Ethics Code First version 1953 Most recent (10th) version 2002 General Principles Principle A: Beneficence and Nonmaleficence— responsible caring—work to benefit others—do no harm B: Fidelity and Responsibility—establish trust and uphold standards C: Integrity—promote accuracy and honesty in science, teaching, and practice of psychology D: Justice—promote fairness and justice E. Respect for People’s Rights and Dignity—rights to privacy, confidentiality, and self-determination APA Standard 1: Resolving Ethical Issues Misuse of work Conflicts between ethics and law Conflicts between ethics and org. demands Information resolutions of violations 1st Reporting ethical violations Cooperating with ethics committees Improper complaints Unfair discrimination against complainants APA Standard 2: Competence Boundaries of competence Providing services in emergencies Maintaining competence Bases for scientific and professional judgments Delegation of work to others Personal problems and conflicts APA Standard 3: Human Relations Unfair discrimination Sexual harassment Other harassment Avoiding harm Multiple relationships Conflict of interest Third-party requests for services Exploitative relationships Cooperation with other professionals Informed consent Psychological services delivered to or through orgs Interruption of psychological services APA Standard 4: Privacy and Confidentiality Maintaining confidentiality Discussing the limits of confidentiality Recording Minimizing intrusions on privacy Disclosures Consultations Use of confidential info for didactic or other purposes APA Standard 5: Advertising and Other Public Statements Avoidance of false or deceptive statements Statements by others Descriptions of presentations/trainings Media presentations Testimonials In-person solicitation APA Fees Standard 6: Record Keeping and Documentation of work and maintenance of records Maintenance, dissemination, and disposal of records Withholding records for nonpayment Fees and financial arrangements Barter with clients/patients Accuracy in reports to payers and funders Referrals and fees APA Standard 7: Education and Training Design of training programs Descriptions of training programs Accuracy in teaching Student disclosure of personal information Mandatory individual or group therapy Assessing student and supervisee performance Sexual relationships with students and supervisees APA Standard 8: Research and Publication Institutional approval Informed consent to research Informed consent for recording and photos Client, student, subordinate research participants Dispensing with informed consent for research Offering inducements for research participation Deception in research Debriefing Human care and use of animals in research Reporting research results Plagiarism Publication credit Duplicate publication of data Sharing research data for verification Reviewers APA Standard 9: Assessment Bases for assessments Use of assessments Informed consent in assessments Release of test data Test construction Interpreting assessment results Assessment by unqualified persons Obsolete and outdated test results Test scoring and interpretation services Explaining assessment results Maintaining test security APA Standard 10: Therapy Informed consent to therapy Therapy involving couples or families Group therapy Providing therapy to those served by others Sexual intimacies with current therapy clients Sexuality intimacies with the relatives or sig. others of current therapy clients Therapy with former sexual partners Sexual intimacies with former therapy clients Interruption of therapy Terminating therapy B. NASP Principles for Professional Ethics Most recent version 2010 Essentially contains all of APA ethics code More direct reference to school role (vs “therapy” or “research” in APA code) and school contexts and situations. Will cover here what is different. Common terms used: Client (whoever the SP establishes professional relationship with) Child (0-18) (“Student” more vague) Informed consent and assent Parent (includes many) Advocacy (does not include insubordination) School-based vs private practice NASP Four Principles for Professional Ethics General Principles 1) Respecting dignity and rights of all persons 2) Professional competence and responsibility 3) Honesty and integrity in professional relationships 4) Responsibility to schools, families, communities, the profession, and society [APA has 5 broad principles, but the two really include the same things when you break the two codes down—NASP has more school context specific examples] NASP General Principle #1: Respecting dignity and rights of all persons Autonomy and self-determination (consent and assent) Privacy and confidentiality Fairness and Justice NASP General Principle #2: Professional competence and responsibility Competence Accepting responsibility for actions Responsible assessment and intervention practices Responsible school-based record keeping Responsible use of materials NASP General Principle #3: Honesty and integrity in professional relationships Accurate presentation of professional qualifications Forthright explanation of professional services, roles, and priorities Respecting other professionals Multiple relationships and conflicts of interest NASP General Principle #4: Responsibility to schools, families, communities, the profession, and society Promoting healthy school, family, and community environments Respect for law and the relationship of law and ethics Maintaining public trust by self-monitoring and peer monitoring Contributing to the profession by mentoring, teaching, and supervision Contributing to the school psychology knowledge base IV. Law Refresher Three basic sources of public school law: 1) Constitution 2) Statutes and regulations 3) Case law U.S. Constitution No fundamental right to an education Educational rights carved out of amendments 10th—powers of the states 14th—a) equal protection clause Brown v BOE (1954); PARC v Commonwealth of PA (1972); Mills v BOE Distr. Of Columbia (1972) b) procedural due process clause Goss v Lopez (1975) 1st—freedom of speech, etc. Tinker v. DesMoines Indep School District (1969) 4th—search and seizure Merriken v. Cressman (1973) Statutes and Regulations—select examples: Federal Education Legislation ESEA 1965—>FERPA/Buckley 1974, PPRA 1975 (Protection of Pupil Rights Act), NCLB 2001 EHA 1975—>IDEA 1990, 1997, IDEIA 2004 Federal Antidiscrimination Legislation Rehab Act 1973 ADA 1990 CRA 1871 (Civil Rights Act) V. Lawsuits Against Schools Under Position of the courts has generally been to stay out of it. Under state law…. federal law…. IDEA position—attoney fees covered by school if family wins Civil Rights Act position—teachers generally not held personally liable if acting in good faith Paul D. Coverdell Teacher Protection Act—limits on liability when teachers acting in good faith Common Legal Challenges 1) Privacy—not explicitly mentioned in Constitution Case Law decisions have balanced interest of schools (duty to educate) and maintain order and safety with personal freedoms and rights. Students don’t get full rights of general adult citizens. Merriken v Cressman (1973)—right to family privacy/consent New Jersey v TLO (1985)—search and seizure Sterling v Borough of Minersville (2000)—right to student privacy re: sexual orientation. No “genuine, legitimate, and compelling government interest” in disclosing. Statutory Law—FERPA and PPRA 2) Informed consent for SP-client relationship Importance of this is deeply rooted What is a “SP-client” relationship What is not a SP-client relationship Informed consent=knowing, competent, voluntary (clear understanding, legally competent, and willful) Consent of minors Parents hold the rights to choose if child receives tx Courts have ruled that minors are not competent to decide if they need tx. Minors can access psych or medical tx w/o parent consent in emergency situations, and for health-related conditions (STD/Is, substance abuse). Research shows more capability esp in 15-17 year olds, and involving them enables “buy in”. Don’t ask for assent if refusal will not be granted. Can see them 1-2 sessions w/o parent consent. 3) Confidentiality Primarily a matter of ethics, but could be held civilly liable. 3 issues: SPs define parameters at the outset, only disclose to others on “need to know” basis, and consider sensitive info as belonging to the student/family an not the school—student and parent control who knows what. Direct Services to the Student (e.g., individual counseling) Minor generally has no legal right to confidentiality irrespective of the parent Best practices to be clear up front about parameters and why you might have to disclose to protect the student. No clear guidance on what constitutes reasons for breaking confidentiality with a minor. But don’t promise it if it could be broken. Disclose when student requests it, when student or others are in danger, if required by court of law. When feasible, get student assent before disclosure Enlist partnership with student in problem solving through the disclosure process. Duty to Protect in school-based practice—reasonably foreseeable risk of harm vs clear and imminent danger. Must have good reason, or risk malpractice suit. Collaboration and Confidentiality (e.g., with parents— what to share with teachers/admin) Establish clear agreement with “client” re: confidentiality parameters. Information shared is discussed only for professional purposes--on a “need to know” basis. Not supposed to share more than needed with teachers if not relevant to teacher ability to work with the child effectively. Confidentiality and Teacher Consultation The guarantees of “client confidentiality” apply here. All shared must be kept confidential unless one of three reasons to break confidentiality. Pressures from admin to give info. Confidentiality=ethical notion Privilege=legal notion 4) Privileged Communication Must set parameters at the outset (e.g., People v Vincent Moreno, 2005) When info gathered and shared as part of MET, communications are not privileged (JN v Bellingham school district, 1994) Consult an attorney when unsure b/c if disclose when shouldn’t, could get sued. Subpoenas and court orders Subpoena used by attorneys and individuals to gather info (usually issued by clerk); court order a command by judge to produce documents, appear in court and answer questions. Don’t give up info for subpoena unless client permits For court order, have to comply or be held in contempt of court. 5) Record keeping in the schools Pre-1970, many abuses of school records identified, e.g., releasing info to police, creditors, employers, etc., w/o permission, parents had limited access or procedures for challenging contents of records, wide variety of people accessed records, procedures for regulating access rarely existed. Thus, FERPA in 1974—requires schools to have written policies sent annually to parents re: access to and confidentiality of education records. Education Records=contents maintained by school, including MET evaluation/spec ed documents such as test protocols. Does not include a)directory information, b) medical or related evals NOT used as part of instructional program, and c) “sole possession records” (aka “memory aids”), unless they were shared w/ others and then they are no longer privileged. Right to inspect and review records schools must comply with parent request for access to records within 45 days of the request. If they really can’t come, you have to make copies, including of test protocols. Best to build good rapport and go over all details in the first MET. Right to confidentiality of records School can disclose w/o consent to teachers who have “legitimate educational interests” Right to request amendment of records If inaccurate, is misleading, or violates privacy or other rights of student. Parent access to test protocols Parents have a right to review records. Ideal if rapport built and they are satisfied with your review with them. If not and it goes further, stay calm. FERPA does not require notice to parents before destruction of materials no longer needed (e.g., protocols), but IDEA—Part B does require that parents must be informed before it is done. Don’t destroy things that parents could want to see. Parents have legal right to inspect raw test protocols— conflicts w/ ethics code re test security. If parents can’t get to school for a reasonable time period, have to make copies of protocols even. Some courts have ruled this not copyright violation, but there is not good consensus yet and testing companies are fighting. 6) Least Restrictive Environment Medical needs that can be easily trained for nonmedical staff to implement Holland (1992) and Sacramento Schools v Rachel H (1994) established four-part test for determining compliance with LRE requirement: 1) The educational benefits available in a general education classroom, supplemented with appropriate aids and services, as compared with the educational benefits of a special education classroom, 2) The nonacademic benefits of interaction with children who are not disabled, 3) The effect of the child’s presence on the teacher and other children in the classroom, and 4) The cost of educating the child in the general education classroom. The education of the other children must be significantly impaired to justify exclusion; same for cost—must be significantly more exnsive to justify exclusion Also can’t exclude b/c modifications needed, but Daniel RR v Texas BOE (1989) established a 5th factor that can be considered in determining LRE: 5) whether the child can benefit from the general education curriculum without substantial and burdensome curricular modifications —don’t have to “modify the curriculum beyond recognition.” NOTE: Interesting recent input that I received----that our circuit court(6th circuit court in Cincinnati is our jurisdiction in Michigan) has a different case as our precedent. The case is Ronkers from the mid1980s. Ronkers has essentially a two-prong decision making guideline, primarily factoring in the academic and social benefit to the child himself and not factoring in his/her impact on gender education students/teachers/ setting. But Susan Jacob only includes the California case in her book, so wasn’t sure which gets consulted in Michigan cases, or if it’s both. So, I checked with an attorney who cited the legal concept of Persuasive Authority. Persuasive authority means sources of law that the court consults in deciding a case. It may guide the judge in making the decision in the instant case. But it is not a binding precedent on the court under common law legal systems such as English law. Persuasive precedent may come from a number of sources such as lower courts, horizontal courts, foreign courts, statements made in dicta, treatises or law reviews. Appellate courts may look to rulings in other jurisdictions as persuasive authority, but persuasive authority means that the reasoning advanced in support of the holding is analytically compelling. [State v. Southers, 1988 Ohio App. LEXIS 4648 (Ohio Ct. App., Pickaway County Nov. 23, 1988)]. So, at this point, I am inferring that the California case (Rachel H), as a more recent case and more multi-faceted, is likely consulted in other jurisdictions, such as ours. Scope of required related services—Tatro (1984) spina bifida and catheterization case; Charlene F case (1999) ventilatordependent student and full time nursing care. Both cases favored parents. 7) Appropriate Education/FAPE BOE of Hendrick Hudson Center School District v Rowley (1982) has shaped subsequent cases by establishing two prong FAPE test: 1) Were IDEA procedures followed in developing the IEP? 2) Is the program reasonably designed to benefit the child? Can consider cost if 2 equivalent options available Schools generally have the say in choice if reasonably calculate to have greater than minimum benefit. No guarantee to parents of maximum benefit 8) Implementing RTI Both NCLB/ESEA and IDEA push for EBIs. Courts have supported this in several cases However, must document an RTI plan, progress monitor, and adjust instruction. A 2009 case did award parents compensatory damages b/c of poor RTI and perceived need for special education benefit a year prior. Also cannot require RTI be implemented before evaluating. Best way to handle “premature” evaluation requests? Overall, the implementation of pre-eval interventions/RTI/MTSS is not likely to be seen as unreasonable delay of IDEA “child find” requirements if academic growth is documented and special ed eval conducted when seems necessary. 9) Student self-referrals for counseling Can provide 1-2 emergency sessions w/o parents Must get it after that unless state law/district policy permits “mature minors” to receive it w/o parent consent. For health conditions like substance use, STD/STIs, pregnancy prevention, teens may be able to receive community-based help w/o parent permission (by federal and state laws). SP can refer. FERPA permits parents to see your notes, though, so consider whether notes are necessary. 10) Threats to self Take it very seriously and report to parents and principal after a risk assessment, especially when in doubt and even if risk is confirmed to be low (Poland, 1989) Courts have generally not held schools liable unless grossly negligent/reckless/careless (e.g., Armijo v Wagon Mound Public schools, 1998). 11) Threats to others Schools should take multidisciplinary approach to threat assessment (mental health, school admin, law enforcement, etc.) Schools generally not held liable if took seriously, warned parents, and when propensity to violence unknown in child. 12) When students disclose criminal acts What is our legal duty? 13) Pregnancy, birth control, and STD/Is Alan Guttmacher Institute www.guttmacher.org State laws re: parental consent and for which services: http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/index.html Jacob text: have to know state and local policies STD/Is---All states allow teens to access STD testing and tx. Pregnancy--Arnold v BOE of Escambia, 1990-- no requirement for a school to notify parents of the pregnancy of a minor student under federal or state law SPs should refer to local clinic or sensitive physician. Schools may only have to tell to “safeguard the student’s health and well-being” (how defined?) Encourage student to tell. Access to abortion—34 states require parent consent or notice, but all provide for “judicial bypass”. What Michigan permits 14) Assessment and conducting special education evaluations Clash between organizational demands (e.g., what admin wants) and your ethics 15) Miscellaneous When our peers misbehave? V. Decision-Making Models Why needed? Eight-step problem-solving model (adapted from Koocher & Keither-Spiegel, 2008): 1) Describe the parameters of the situation 2) Define the potential ethical-legal issues involved 3) Consult ethical and legal guidelines and district policies that might apply to the resolution of each issue. Consider the broad ethical principles as well as specific mandates involved. 4) Evaluate the rights, responsibilities, and welfare of all affected parties (e.g., student, teachers, classmates, other schools staff parents, siblings 5) Generate a list of alternative decisions possible for each issue. 6) Enumerate the consequences of making each decision. Evaluate the short-term, ongoing, and long-term consequences of each possible decision, considering the possible psychological, social, and economic costs to affected parties. Consultation with colleagues may be helpful. 7) Consider any evidence that the various consequences or benefits resulting from each decision will actually occur (i.e., a risk-benefit analysis). 8) Make the decision. Consistent with codes of ethics (APA, NASP), the school psychologist accepts responsibility for the decision made and monitors the consequences of the course of action chosen. 2004 APA panel of PhDs and JDs advised psychologists to: 1) Consult with a colleague or ethics expert and consider calling your state board or state psychology association for additional assistance. 2) Document the steps you took and those you considered but didn't take, and your reasoning behind those decisions. 3) Aspire to the general principles in the Ethics Code and consider whether and how the five principles help inform the decisionmaking process. 4) When the law and the Ethics Code conflict, review Standard 1.02, which allows psychologists to follow the law after first making known their commitment to the Ethics Code. 5) If a conflict of interest, such as having a relationship with someone closely associated with a client, can reasonably be expected to jeopardize your objectivity, carefully consider your options, most notably refraining from the relationship. 6) Any time you decide to terminate counseling, follow Standard 10.10: Offer the client a referral to another mental health professional, Kinscherff recommended. http://www.apa.org/monitor/oct04/bind.aspx NASP’s model: What to do when you have to confront an ethical dilemma: http://www.nasponline.org/standards/EPPC_Procedures.pdf Visual flow chart of procedures to follow: http://www.nasponline.org/standards/complaintprocess.pdf VII. Types of ethical complaints: Dailor (2007): >90% of survey respondents had witnessed SPs engage in at least one of nine types of unethical behavior in the prior year. Top Four in clinical settings…. Confidentiality Blurred, dual, or conflictual relationships Payment sources, plans, settings, and methods Academic settings, teaching dilemmas, and concerns about training http://www.kspope.com/ethics/ethics2.php VIII. Common Situations with Implications for Ethical and Legal Knowledge and Decision-Making: Cognitive Errors and Boundary Crossing Decisions: Error #1: What happens outside the psychotherapy session has nothing to do with the therapy. Error #2: Crossing a boundary with a therapy client has the same meaning as doing the same thing with someone who is not a client. Error #3: Our understanding of a boundary crossing is also the client's understanding of the boundary crossing. Error #4: A boundary crossing that is therapeutic for one client will also be therapeutic for another client. Error #5: A boundary crossing is a static, isolated event. Error #6: If we ourselves don't see any self-interest, problems, conflicts of interest, unintended consequences, major risks, or potential downsides to crossing a particular boundary, then there aren't any. Error #7 Self-disclosure is, per se, always therapeutic because it shows authenticity, transparency, and trust. http://kspope.com/ethics/boundary.php IX. Peer Monitoring APA and NASP both state that members must monitor the behavior of their professional colleagues in order to ensure ethical conduct. Start with informal attempts to resolve. Be direct, thorough, and honest with the colleague. Document your efforts, his/her response, and your rationale for what you did and did not do. If effective, consider it a professional success. If ineffective, follow next steps in the decisionmaking models Apply all of this to intern supervision as well. Universities need you to share all concerns with us. X. Self-Monitoring Refresh yourself on ethics and law regularly. Talk with colleagues about challenging issues as they arise, at any stage in your career—we all need to continually learn and seeking consultation is a critical part of it. Make good and ethical decisions as outlined in this presentation and beyond! References Except where noted otherwise, most material was taken from: Jacob, S., Decker, D. M., & Hartshorne, T. (2010). Ethics & law for school psychologists (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. And the APA and NASP ethics codes, which are also included in appendices in Jacob et al. Contact me if you have any questions: c.somers@wayne.edu