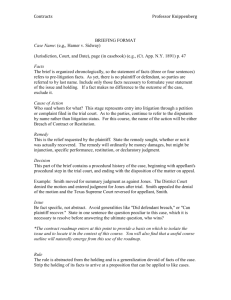

AIPLA Case Summary Q4 2010 - American Intellectual Property Law

advertisement