November 8, 2015 - Vallejo Symphony

advertisement

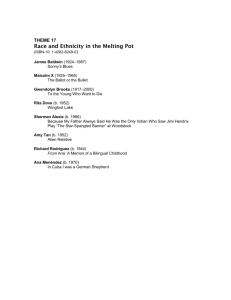

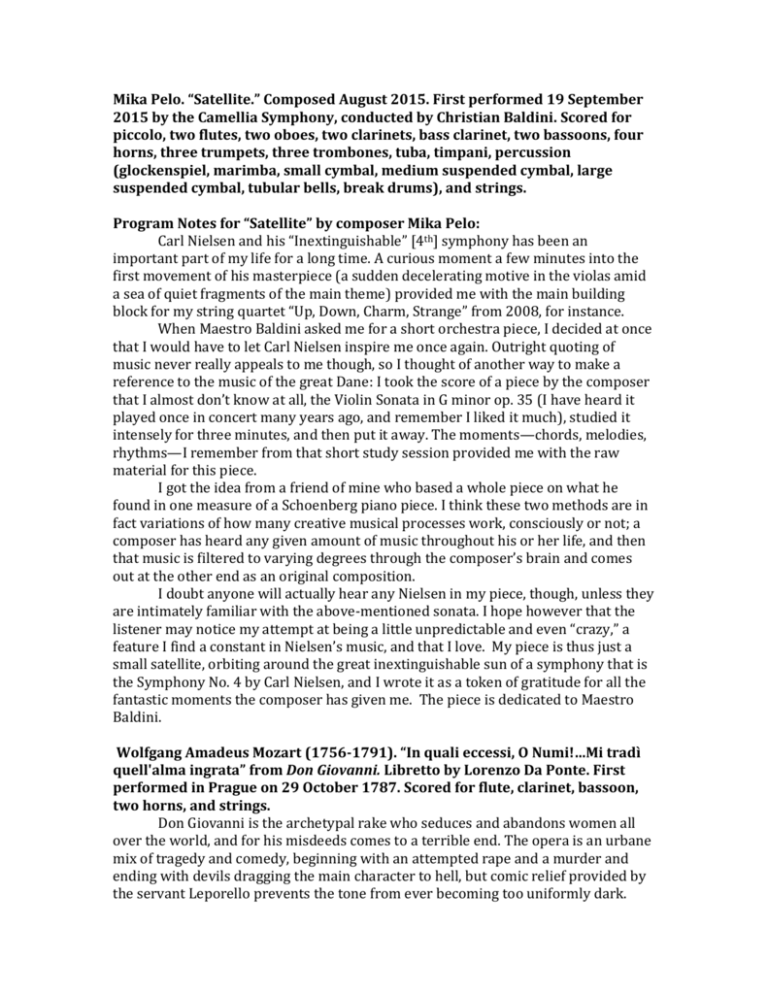

Mika Pelo. “Satellite.” Composed August 2015. First performed 19 September 2015 by the Camellia Symphony, conducted by Christian Baldini. Scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (glockenspiel, marimba, small cymbal, medium suspended cymbal, large suspended cymbal, tubular bells, break drums), and strings. Program Notes for “Satellite” by composer Mika Pelo: Carl Nielsen and his “Inextinguishable” [4th] symphony has been an important part of my life for a long time. A curious moment a few minutes into the first movement of his masterpiece (a sudden decelerating motive in the violas amid a sea of quiet fragments of the main theme) provided me with the main building block for my string quartet “Up, Down, Charm, Strange” from 2008, for instance. When Maestro Baldini asked me for a short orchestra piece, I decided at once that I would have to let Carl Nielsen inspire me once again. Outright quoting of music never really appeals to me though, so I thought of another way to make a reference to the music of the great Dane: I took the score of a piece by the composer that I almost don’t know at all, the Violin Sonata in G minor op. 35 (I have heard it played once in concert many years ago, and remember I liked it much), studied it intensely for three minutes, and then put it away. The moments—chords, melodies, rhythms—I remember from that short study session provided me with the raw material for this piece. I got the idea from a friend of mine who based a whole piece on what he found in one measure of a Schoenberg piano piece. I think these two methods are in fact variations of how many creative musical processes work, consciously or not; a composer has heard any given amount of music throughout his or her life, and then that music is filtered to varying degrees through the composer’s brain and comes out at the other end as an original composition. I doubt anyone will actually hear any Nielsen in my piece, though, unless they are intimately familiar with the above-mentioned sonata. I hope however that the listener may notice my attempt at being a little unpredictable and even “crazy,” a feature I find a constant in Nielsen’s music, and that I love. My piece is thus just a small satellite, orbiting around the great inextinguishable sun of a symphony that is the Symphony No. 4 by Carl Nielsen, and I wrote it as a token of gratitude for all the fantastic moments the composer has given me. The piece is dedicated to Maestro Baldini. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791). “In quali eccessi, O Numi!…Mi tradì quell'alma ingrata” from Don Giovanni. Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. First performed in Prague on 29 October 1787. Scored for flute, clarinet, bassoon, two horns, and strings. Don Giovanni is the archetypal rake who seduces and abandons women all over the world, and for his misdeeds comes to a terrible end. The opera is an urbane mix of tragedy and comedy, beginning with an attempted rape and a murder and ending with devils dragging the main character to hell, but comic relief provided by the servant Leporello prevents the tone from ever becoming too uniformly dark. Poor Donna (Lady) Eliva! Don Giovanni loved her and left her, but she loves him still. This aria expresses her ambivalence—clear-eyed, she sees his crimes for what they are and hopes for divine vengeance, yet she pities him for the terrible retribution she sees in his future. Donna Elvira is introduced in Act II of Don Giovanni, and she has scenes with several characters: slinging accusations with Don Giovanni himself, being treated to a reading of the Don’s little black book by his servant Leporello, and saving the innocent Zerlina from the predator’s clutches. When she sings this solo aria, she is alone, and the aria is not at all necessary for the plot, although it fits thematically with what has happened before and what is to come. The reason the aria seems detached from the rest of the action is simple: Mozart composed it for Viennese soprano Caterina Cavalieri (1760-1801), one of the preeminent sopranos of her day, when she complained that she didn’t have enough to sing in the Donna Elvira role. (Cavalieri appears as a character in the fictionalized 1984 film about Mozart, Amadeus.) The aria consists of two parts: an “accompanied recitative,” a slow, melodic beginning that almost has the cadence of speech, and in which no lines are repeated; and the aria itself, a song in which lines and verses are repeated, each time with more complex ornamentation—a way of showing off the soprano’s skill and talent as it expresses the character’s emotional state. ________________________. “E Susanna non vien…Dove sono” from Le Nozze di Figaro. Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. First performed in Vienna on 1 May 1786. Scored for two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, and strings. The Marriage of Figaro is based on a pre-revolutionary play by the French writer Beaumarchais (1732-1799) called La folle journée, où le Mariage de Figaro (The Crazy Day, or The Marriage of Figaro), first performed in 1784. Banned in several European countries, the play commented cynically on the privileges of the upper classes and their relations with the people who serve them—a kind of 18th-century “Upstairs Downstairs” with irony, cross-dressing, and improbable intrigues. The Count Almaviva, who, in Beaumarchais’ earlier play The Barber of Seville, hired the clever barber Figaro to help him woo and wed Rosina, has now become a serial womanizer, abandoning, Rosina the Countess to her bitter thoughts, while he tries to seduce her servant Susanna, soon to be Figaro’s bride. (The Barber of Seville was made into an opera thirty years later by Gioachino Rossini.) Susanna, Figaro, and the Countess join forces to teach the Count a lesson. At the start of Act III, the Countess sets her plan in motion: she dispatches Susanna with a note to the Count and instructs her to pretend that she is willing to respond to his advances if he will meet her in the garden that night. Of course, when the Count arrives in the garden that night he finds his wife disguised as Susanna and vice versa. Seeing Figaro with Susanna, he thinks he sees Figaro trying to seduce the Countess, and then finds that the woman he himself has been trying to seduce is his own wife.) As the Countess waits for Susanna’s return, she sings this aria in which she thinks back on how the count has wronged her and regrets the passing of the days when they were happily in love. Again, this aria is preceded by an accompanied recitative. The aria itself is one of the most moving and evocative melodies in the repertoire. Ideally sung by a lyric soprano, the long, soft melodic lines should spin out like silk. (Mozart also cleverly inserts a few orchestral reminders of the “wedding music” of the overture.) The last few lines have a triumphal mood, as the Countess deplores her husband’s “ungrateful heart” and looks forward to her hoped-for victory. Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901). “Tu che le vanità” from Don Carlo. Libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille de Locle. First performed as Don Carlos in Paris on 11 March 1867. Scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings. Based on a play of the same name by German Romantic writer Friedrich Schiller, Don Carlo(s) exists in several different versions. It was first performed in Paris (in French), then in Bologna (in Italian), and later in Modena and Milan, all in different versions. It exists in four acts and also in five. The play was based on historical events, or at least uses these events for its backdrop. In 1568, in the forest of Fountainebleau, Don Carlos, the son and heir of Philip II of Spain, meets the woman to whom he is betrothed in an arranged marriage: Elisabeth de Valois. Meeting for the first time, they find that they are soul mates. Suddenly, Elisabeth is informed that she will be married to Don Carlos’s father Philip instead, as part of the peace treaty ending the Italian War of 1551-59. From there, the plot becomes more and more complex, with a scheming character named Eboli framing Carlos because he doesn’t return her affection, hoping to have him executed at an auto-da-fé by the Spanish Inquisition. In Act V, Elisabeth prays before the tomb of King Charles V as she waits to see Carlos one last time to say good-bye. After this aria, while the two say their farewells, King Philip and the Grand Inquisitor enter and capture the pair. Suddenly a shadowy monk (apparently the ghost of the dead king, Charles V, which also appeared earlier in the opera) comes out of the tomb and takes Carlos away with him, as everyone reacts in horror. Like the other arias we are hearing tonight, this aria follows Elisabeth’s thoughts and feelings as she has them. Some lines are repeated at the beginning and the end, set off by complex and varied orchestration. This is the best-known aria from Don Carlo, a riveting complaint from a broken heart with a beautiful, subtle orchestra accompaniment. Robert Schumann (1810-1856). Symphony No. 1 in B-flat Major Op. 38 “Spring.” Composed January–February 1841. First performed in Leipzig on 31 March 1841 with Felix Mendelssohn conducting. Scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, triangle, and strings. As a teenager, Robert Schumann had wanted to pursue a career in music, an aspiration approved of by his father, who also encouraged him to read widely in Romantic literature. But when Robert was 16, his father died, and he was forced by the terms of his inheritance to study law. “My whole life,” he wrote to his mother when he was 20, “has been a struggle between Poetry and Prose, or call it Music and Law.” A man of strong feelings, Schumann was preoccupied with symbolic dualities, to the point where he created two alter egos with opposing temperaments— Florestan, the active aspect of his personality, and Eusebius, the passive dreamer. Schumann suffered from serious periodic depressions when he was unable to compose or even function—complicated by auditory and visual hallucinations; premonitions of death; delusions of persecution; and a fear of heights, poisons, drugs, and metal objects, even those as apparently innocuous as keys—alternating with periods of feverish inspiration and productive composition at an almost superhuman speed. The Symphony No. 1 was sketched out in four days’ time and orchestrated in another month. With all his quirks, Schumann was a magnificent innovator, and above all, a Romantic who believed that form followed function, rather than the other way around—that the intention or inspiration of a work should dictate its form, even if that meant that every work had a unique form. (“As if each work of art had not its own meaning and consequently its own form!” he once wrote.) Instead of composing pieces with traditional titles that described their forms (caprice, rondo and variations, sonata, etc.), he often named his pieces for the emotions or visions that had inspired them: “Papillions,” (Butterflies), “Kreisleriana,” “Fantasy,” and so on. He specialized in shorter compositions—he only composed four symphonies— that produce an emotional impression or a picture. His symphonies are written in the classic Sonata-Allegro form (a slow Introduction; an exposition, introducing the themes; a development section; a recapitulation, or a restatement of the themes; and an optional Coda, or “tail,” to finish off the work), but they still present unique emotional responses to the form. An excellent writer, Schumann thought deeply about music and had strong opinions about what he heard, expressing them without hesitation in the journal he founded 1834, Die Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (The New Review for Music). He “discovered” Chopin and Brahms, tirelessly vaunting the talents of young composers to the world. Unfortunately, being an unassuming man, he did not spend much energy promoting his own work. After Robert’s death, his widow Clara and their young friend Brahms worked tirelessly to popularize his music. In 1840, just after his marriage to Clara, he experienced a huge creative outpouring, during which he composed 138 lieder (songs for piano and voice). The following year he composed two symphonies, the First and the Fourth (later revised). The Symphony No. 1 does not attempt to represent spring, with its characteristic sounds, in the way that Vivaldi’s Four Seasons does, for instance— rather, it expresses the emotional states evoked by springtime: starting with the longing for spring from the depths of an icy Northern European winter (longing, as opposed to fulfillment, being a quintessential Romantic theme), and ending with the full-on celebration of spring’s energetic arrival. The first movement, with the tempo marking Andante un poco maestoso– Allegro vivace, was originally called “Spring’s Awakening” by Schumann. Its majestic exposition begins with a fanfare corresponding to the rhythm of the closing lines of a poem by Schumann’s friend Aldoph Böttger: “O wende, wende deinen Lauf—/ Im Thale blüht der Frühling auf!” (“Oh turn, oh turn and change your course—/ Now in the valley spring blooms forth!”). After the horns and trumpets play alone, the rest of the orchestra joins them, cheerfully announcing springtime. But spring hasn’t really arrived yet—a rising scale in the strings introduces troubled, wintry music. Like the changeable weather in early spring, the music here sweeps through several radical emotional changes in just a few lines. Chords precede more tranquil music that quickens until we are in the Allegro vivace section, where one theme is based on the opening fanfare and a secondary—more subdued—theme is played by the woodwinds. The development section proceeds in the same style—each echo of the cheerful theme is cut off by a melancholy reminder of winter, and so our emotions are buffeted about as if by spring’s unruly winds. In the double coda, the music quickens into double-time before slowing for a tranquil melody by the winds (with sweet a flute solo) before a triumphal ending. The Larghetto second movement was originally called “Evening” by Schumann. Its beautiful, haunting melody, punctuated by stately trills and gentle broken chords, is handed around the orchestra from section to section, but with an unbroken melodic line. A quick rhythm of staccato notes provides a needed interruption of the serene melody, and syncopated entrances prevent the sweetness from becoming cloying. At the end, the trombones enter for the first time since the opening movement, playing very softly the theme of the Molto vivace (very lively) Scherzo (originally entitled “Merry Playmates”), which begins immediately afterwards. The Scherzo’s dance-like main theme is heavily accented, while the two trios offer completely different sounds and emotions. The first is a simple country dance, while the second, with its varying tempos and emotional capriciousness, does not prepare us for the emphatic scale that leads without pause to the finale. The relatively brief Allegro animato e grazioso (animated and graceful) movement was originally entitled “The Height of Spring,” but Schumann said in a letter to a friend that it should also be considered a farewell to spring. (Again, this is a familiar Romantic conceit—as we are in spring, we already anticipate its ending.) But there is little or nothing melancholic about this irrepressible movement. The mischievous, mincing theme in the strings plays a game of hide and seek with a contrasting minor-key theme in the woodwinds that eventually itself turns cheerful. During the recapitulation, when we have nearly reached the end, the horns that began the piece conspire with the oboe to try to turn the mood darker. But the flute intervenes with a trill and an irreverent little solo that returns us to the mischievous opening theme. The coda is pure joy. © 2015 Mary Eichbauer