It can be argued that an increase in human capital among the poor

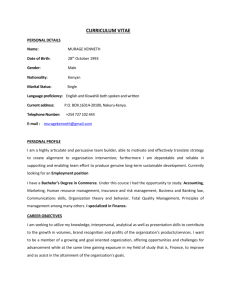

advertisement

1 Indhold 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1.1 Introduction to host organisation ........................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Problem formulation ................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Empirical background .................................................................................................................................. 8 1.5 Theoretical background ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.5.1 The Solow model .................................................................................................................................. 9 1.5.2 Verspagen’s theory on catching up or falling behind ......................................................................... 11 2.1 Analysis ...................................................................................................................................................... 13 2.1.1 Solow .................................................................................................................................................. 13 2.1.1.1 Sub conclusion ............................................................................................................................. 16 2.1.2 Verspagen ........................................................................................................................................... 16 2.1.2.1 Sub conclusion ............................................................................................................................. 19 2.2 Discussion of the relationship between equality and economic growth .................................................. 19 2.3 Critical discussion of NGO’s work .............................................................................................................. 21 2.4 Are the findings universal? ........................................................................................................................ 22 2.5 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................. 23 2.6 Bibliografi................................................................................................................................................... 24 2 Figures Figure 1 The dynamics of Verspagen's theory................................................................................................. 12 Figure 2 Education expenditure (% of GNI) ..................................................................................................... 13 Figure 3 Kenya's growth in GDP (%) ........................................................ Ошибка! Закладка не определена. Figure 4 GDP per capita growth (annual %) ............................................ Ошибка! Закладка не определена. Figure 5 GDP per capita growth (annual %), moving average for a 3 year period .......................................... 17 Figure 6 The dynamics in Kenya ...................................................................................................................... 17 3 1.1 Introduction The world today is of many considered unequal. In fact, some people are suggesting that the world is becoming still more unequal1. Figures show that in 2011 the richest 20 per cent of the world population had over 70 per cent of the total world income (UNICEF, 2011). This is a problem because it means that a big share of the world population is still living in deep poverty without getting their basic needs met. They are living below the dollar-a-day poverty line set by the UN. This paper’s focus is on how economic development, measured by economic growth and economic equality, can be improved through an increase in human capital. The basic assumption of the paper can be formulated on Lucas’ (1993) argument: “The main engine of growth is the accumulation of human capital of knowledge and the main source of differences in living standards among nations is differences in human capital”. In measuring human capital the main focus will be put on education since this is the focus of the host organisation for the writer’s internship. This is relevant because education can be seen as one of the keys for countries to develop economically and escape poverty, and because knowledge empowers people and gives basic tools to improve living conditions and thereby a hope for a better future. Also, it has been shown that uneducated girls face a greater risk of getting HIV/AIDS, child trafficking and sexual exploitation (Ahn & Silvers, 2005). The specific basis will be in Kenya where education is put high on the official agenda. In January 2003 Kenya’s Free Primary Education Policy was implemented which means that every child in Kenya can now go to primary school for free (Ahn & Silvers, 2005). However, there are still costs connected with going to school like transport and the obligatory school uniform that the children are supposed to bring themselves. Despite of this it is still a fact that the 2003 policy has made a great impact on many children and their futures, and that in the 2012 Kenya even children living in slums or orphanages has the possibility of going to school. Thereby they get an opportunity to escape the social inheritance that they would otherwise have been trapped in. Because of this, even though the paper has a main focus on human capital’s importance regarding economic development, it can be argued that it also makes up a positive externality in terms of a row of both political and social factors, and that it thereby has a positive effect on all aspects of society. However, it is acknowledged that even though an increase in human capital has many positive effects on a society it does not necessarily lead to a more equal society. An increase in human capital can, though, constitute one of the tools to achieve this, which should be seen as the ultimate long run goal. Therefore, the paper will focus on growth in the analysis. After this, there will be a discussion on the connection between economic growth and economic equality. 1 It is, however, important to underline the fact that it is nearly impossible to measure if this is correct because of several factors which is why some argue that the world is becoming more unequal while others argue the opposite. This because there are several factors that are hard to measure in informal economies. These are among others the consumption level of the citizens, an exact way to measure to be able to compare values across borders (where PPP is now being used), and an appropriate basis of comparing countries (The Economist, 2004) 4 1.1.1 Introduction to host organisation Sauti Ya Wanawake2 is a non-governmental organisation started in 2001 by Action Aid that focuses on helping women and minority groups in having their basic rights fulfilled. It started out with the purpose of creating a safe space for women to discuss the issues that they were facing in smaller forums where the women could stand together and fight for their rights. In 2012 SYW was made into an organisation itself without being a direct part of Action Aid anymore. However, Action Aid still contributes financially to several of the projects SYW are conducting. SYW has since developed towards having a main focus is to empower women through education. That means that many of its activities are forums where women, men and youth are educated in different topics such as basic human rights, gender based violence, civic education concerning especially the new constitution from 2010 and what has changed relevant for the target group, and women leadership leading up to the coming election in March 2013. SYW currently have three donors, where Action Aid is the main donor, followed by Pact and International Rescue Centre, both funded by US Aid. This means that in its work SYW is also, through educating people, helping in the process of increasing human capital in Kenya. 1.2 Problem formulation Even though Kenya is the biggest economy of East Africa it still faces problems concerning establishing a sustainable economic development that will benefit all layers of the Kenyan society. Among others there is still a high level of corruption which puts Kenya in the bottom of Transparency International’s Corruption Index, a low ranking in the HDI index, high unemployment among especially the youth, tribalism which causes cleavages in society, a high dependency on foreign aid, and social inequality with most of the population still live below the official UN poverty line. However, because of its size, relative stabile situation, and increasing growth rates it is a country of great potential and therefore also a country that is very relevant to look at for a development student. Within the last decade Kenya has focused considerably on education and what benefits this can bring for the country both economically, politically and socially. In this concern many NGO’s have followed, SYW being one of them. This leads to the following problem formulation: How do increases in human capital influence economic development in Kenya, measured by economic growth and economic equality? Human capital is defined as the knowledge and experience that the labour force in a given country has. It can be positively affected through education and training, and the level of it is decided by the individual person trough a consideration of the costs connected with increasing its educational level and the benefits received when the higher educational level is attained (Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi). Also, human capital can include a country’s investments in R&D. However, the main emphasis in this paper will be put on the aspect of education. In case specific cases or observations are needed SYW will provide the empirical knowledge for this. 2 Translates to ”women’s voice”. In the following abridged to SYW 5 As the problem formulation indicates the paper will focus on the economic aspect of the increase in the general educational level. The reason of the delimitation is that it is found necessary to be able to analyse the topic in depth. Another limit in the analysis is time, even though it is acknowledged that all of a country’s history matters for its further development. Here the primary focus will be on the period after the colonisation in 1963 where Kenya reached its independence and up to the 21st century. 1.3 Methodology This part will set out and explain the scientific approach, research design and survey method that is being used in this paper. This is of great importance for the outcome since if one of these were changed this would change as well. This paper uses critical realism as its scientific approach. This approach has the ontological perception that reality exists independently of the observing subjects’ conscience. Epistemologically, the approach believes that the reality that is seen in the world can be understood indirectly only, and that what agents see as the true reality are only apparent phenomena. Agents must through a critical and rational analysis get as close to the truth as possible. However, because of the uncertainty that will naturally happen due to the fact that things are seen objectively it is important to underline that agents, even though it is the ideal, cannot reach a definite, objective truth (Langergaard et al., 2006). The research design used in this paper is a single unit analysis where it will argue for the importance of human capital in order to assist economic growth, and how a specific local organisation is helping this development through its work. The reason why the single unit design is found useful to conduct this specific analysis is that it is a flexible research method concerning duration and size. The consequence of using this research design is that it is an analysis that is specifically made for Kenya and therefore the results cannot be directly applied to other countries. This because the method cannot be used to find results that can be generalised statistically because of the small statistical population. Instead, it provides an explanation of the case of Kenya (de Vaus, 2007). About case studies Robert K. Yin writes: A major rationale for using (case studies) is when your investigation must cover both a particular phenomenon and the context within which the phenomenon is occurring either because (a) the context is hypothesized to contain important explanatory information about the phenomenon or (b) the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident (de Vaus, 2007, p. 235). Human capital and the changes that are seen in this factor is the phenomenon in this paper while Kenya is the context. It is therefore relevant to investigate how these two are affecting each other and if there can be found a dualistic relationship between them. The context could involve more countries than Kenya, e.g. other African countries or developing countries in general, which would make up for a multiple case design. However, no country has experienced the exact same events historically. Especially the former colonies have responded differently to their independence in the 1960’s and therefore also developed differently afterwards, both politically, socially and economically. Also, there have been differences in e.g. the amount of financial assistance the developing countries have received. Therefore, not even comparing Kenya to 6 Uganda and Tanzania would be suitable because the case of Kenya is rather unique, and that is why the single case design is found better in this particular analysis (de Vaus, 2007). The survey method of the paper is the document study. Thus the paper will take a retrospective approach since past events are found important in order to be able to explain the current situation. In practice historical events will form the basic foundation for the understanding of how the Kenyan economy is being influenced by changes in human capital. Thus the tendencies analysed will be specifically related to Kenya (Duedahl & Jakobsen, 2010). When the document study is being used it is very important that the data being used are at an academic level suitable for a paper at master’s level. Conclusions should be based on empirics that are objective and valid. To test the empirics used in this paper, all sources will be validated from the following four criteria: Credibility, representativity, meaning, and authenticity (Duedahl & Jakobsen, 2010). Firstly, to avoid ulterior motives, selectivity and subjectivity from the writer and thereby assuring that the sources are objective the empirics’ credibility must be evaluated. In this paper this is avoid by only using material that are found from credible sources. Because of this all sources is found to live up to this criterion. Secondly it is important that the parts of the empirics that are being used represent the whole meaning. This again to avoid subjectivity and it is especially important if many different sources are being used. Also, this has been taken into consideration through the writing process as well as more than one source is often used to support the arguments. The third criterion, meaning, deals with whether the meaning of the empirics are easy accessible when reading the texts. Since all sources used are either written in Danish or English this criterion is met. Lastly, it is important that the empirics are authentic, meaning that they are used in their original form and not for instance manipulated in any way. To avoid this all empirics used in this paper are used in its original form. In case web pages have been used the day it was retrieved will be mentioned in the bibliography since it can be edited from time to time. Also, books will be stated with their number of edition (Duedahl & Jakobsen, 2010). Since the four criteria have been met, the empirics that have been used are found valid to draw an objective conclusion. 7 1.4 Empirical background Kenya is a former British colony and reached its independence in 1963 with Jomo Kenyatta as the founding president. The characteristics of the period of his rule are domestic peacefulness with military interventions in both Uganda and Somalia. The conflict with Uganda was the main reason for the end of the East African common market in 1977, only ten years after its establishment. The end of the 1970’s is characterised by economic crisis with a decreasing GDP, increasing unemployment and a feeling of powerlessness among the citizens. This was fought with high amounts of aid and loans from mainly the World Bank. Also, an increase in coffee prices helped Kenya getting out of its economic crisis. When Kenyatta died in 1978 Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi was elected president which lasted for 24 years. Even though Kenya had already been a de facto one state party state through the period from 1969 to 1982, Kanu, Kenya African National Union, felt the need to make itself the single legal party in Kenya. In 2002 Mwai Kibaki and NARC, the National Rainbow Coalition, was elected president which ended the almost 40 years of rule by Kanu, after a decade of both internal and external fighting for political liberalisation. Despite many years of trying to improve the general situation in Kenya, the county still faces serious challenges concerning corruption, social inequality and a vulnerable economy among others. Furthermore, Kenya consists of 42 tribes which during times have led to ethnically based violence among the different tribes. In 2007 Kenyatta was re-elected in an election that made many Kenyans question if was a case of vote rigging. This led to post election violence where as many as 1,500 people were killed because of dissatisfaction with the result of the election. In 2010 the Kenyan government passed a new constitution that eliminates the power of the prime minister after the next election in March 2013. Also, it gave more rights to women and vulnerable groups in society (Central Intelligence Agency, 2012). From an economically point of view Kenya’s history from its independence is characterised by two periods. The first period from 1963 to 1980 is characterised by high positive growth rates, however volatile, of an average of 5 and 8 per cent respectively in the two decades. The second period from the 1980 on the other hand is characterised by more stagnant or even negative growth rates with an average growth rate of 4 and 2 per cent in the two decades. The last decade from 2000 the growth rates has been just below 4 per cent on average (Legovini, 2002). The reason for the economic success in the early years was a successful distribution of productive land to small farmers along with heavy promotion of cultivation, which caused the rural income to increase. While Kenya, as most of the world, was hit economically by the oil crises of the 1970’s a boom in coffee prices in the middle of the 1970’s helped improving the situation. In the 1980’s Kenya carried out a number of reforms as a result of the effects of the second oil crisis which had great effects on both the public deficit and the inflation rates. This was well seen among donors, and the inflow of aid more than doubled during the 1980’s from 6 per cent of GNI to 13 per cent. However, this did not lead the positive economic situation to continue. The external debt increased dramatically, assisted by a devaluation of the Kenyan Shilling in 1993, inflation increased to its pre 1970’s level and the external externally towards both donors and potential investors fell (Central Intelligence Agency, 2012; BBC News Africa, 2012; leksikon.org, 2012). 8 1.5 Theoretical background The paper will take its basis in two theories, the Solow model and Verspagen’s theory on catching up or falling behind. 1.5.1 The Solow model The purpose of this part is to show the Solow model. First the simple model will be explained and then it will be extended to also include human capital. Thus the Solow model with technology is left out because it is not found relevant in this context. The theory is based on Jones (2002) who will be the source unless other references are mentioned in the text. The Solow model focuses on what it calls steady state which denotes the points where the economy is in equilibrium. Therefore it focuses on the long term effects. The assumptions that make the foundation for the model is that there is a constant return to scale, meaning that if K and L are increased with the same factor, Y will increase equivalently. There is perfect competition and only one homogeneous good. Moreover, it is assumed that the agents saving rates are constant, denoted by s, and that they use a constant amount of their time on accumulating knowledge. The simple model explains how input, capital and labour, becomes output. It focuses on the two equations for input. The first equation is a product function while the second is a capital accumulation function. The product function is a Cobb-Douglas function: (1.1) 𝑌 = 𝐹(𝐾, 𝐿) = 𝐾 α 𝐿1−𝛼 . where Y denotes output, K is capital, L is labour and α is a number between 0 and 1. To find the output per worker equation (1.1) is rewritten to the following: 𝑦 = 𝑘𝛼. (1.2) Equation (1.2) shows that capital per worker has decreasing returns to scale, meaning that every time capital is added the output will increase relatively less. This leads to the capital accumulation function: (1.3) 𝐾̇ = 𝑠𝑌 − 𝑑𝐾. where sY denotes the total number of gross investments while dK is the write-off on K as a consequence of it being used in the production. The dot symbols time which makes 𝐾̇ denote the change in the stock of caital for a period. This means that the change in the capital stock equals the total gross investments minus the write-off of K that happens since K has undergone a production process. To examine the development in output per person the capital accumulation can be rewritten as to show capital per person. Thus equation (1.2) will show the output the single worker can produce at a given amount of capital. Here it is assumed that the growth in the rate of labour is constant and that the rate of increase in population is given by 𝑛1 . The following shows equation (1.3) rewritten to show capital per person: (1.4) 𝑘̇ = 𝑠𝑦 − (𝑛 + 𝑑)𝑘. From (1.4) it can be seen that k is growing in time with investments per worker, sy, while k is reduced when there is an increase in the write-off per worker, dk, and an increase in the population, n. Equation (1.2) and 9 (1.4) will be used to examine how output per labour is developing in the long run which leads to the question about how economic growth is created. To this a so-called steady state is used. Steady state is defined by the point where the economy has reached its equilibrium. Concerning capital per worker this point is defined from the fact that 𝑘̇ = 0. Equation (1.2) and (1.4) make the definition usable to solve the level of steady state of capital per worker and output per worker. Put together the equations look the following: 𝑘̇ = 𝑠𝑘 𝛼 − (𝑛 + 𝑑)𝑘 The equation is put equal zero and rewritten to the following: (1.5) 𝑠 1/(1−𝛼) (1.6) 𝑘∗ = ( ) 𝑛+𝑑 . Equation (1.6) is put in the product function (1.1) to find the steady state level for output per worker, y*: 𝑠 𝛼/(1−𝛼) 𝑦∗ = ( ) 𝑛+𝑑 (1.7) To be able to better explain economic growth Solow after his first model chose to expand his theoretical approach to also include technology and human capital respectively. Since this paper focuses on human capital and its positive effects on growth, the focus will be on the Solow model including human capital rather than technology. Again the starting point is a Cobb-Douglas production function, where workers, L, are replaced with skilled labour, H: (1.8) 𝑌 = 𝐾 ∝ (𝐴𝐻)1−∝ , 𝜓𝑢 where 𝐻 = 𝑒 𝐿 and u denotes education so that if 𝑢 = 0 then 𝐻 = 𝐿. 𝜓 is a positiv constant that explains the effects of education on Y. Thereby, an increase in this factor will lead to an increase in the skilled labour’s efficiency. Thus the workers accumulate human capital by spending time on education rather than on working. Since capital is still seen as an important factor the following equation is listed: (1.9) 𝑘̃̇ = 𝑠𝑘 𝑦̃ − (𝑛 + 𝑔 + 𝑑)𝑘̃ where s is now denoted as sk to show that it is investments in physical capital and not human capital. The steady state levels of 𝑘̃ and 𝑦̃ is given by putting 𝑘̃̇ = 0: 𝑘̃ 𝑠𝑘 = 𝑦̃ 𝑛+𝑔+𝑑 (2.0) This is put into the product functions: 𝛼 𝑠𝑘 )1−𝛼 𝑛+𝑔+𝑑 If this is rewritten to output per worker equation (2.1) becomes: 𝑦 ∗ (𝑡) = ( 𝑦 ∗ (𝑡) = ( ∝ 𝑠𝑘 )1−∝ ℎ𝐴(𝑡). 𝑛+𝑔+𝑑 (2.1) (2.2) 10 From equation (2.2) y can be interpreted as productivity. That means that in the steady state level the output per worker grows with the level of technology as well as the level of human capital, since education increases the productivity. It can also be seen that education only has a long term effect on y denoted by 𝑦 ∗ (𝑡), and not growth in the short run. This due to the fact that that an increase in growth on short term only will happen until the effects of education are exhausted. Thus, the way to create long term growth is by constantly investing in education and thereby improve the general level of education and increase the level of human capital. Another interesting point that can be used from the model is that the longer a country is from its steady state level, the greater the potential to increase investments so that the capital per worker will increase. 1.5.2 Verspagen’s theory on catching up or falling behind To analyse whether Kenya has been able to catch up to the United States Verspagen (1991) is used. Verspagen criticises the prevalent neo classical argument that because of technology spill overs developing countries automatically catch up because of leapfrogging (Brezis, Krugman, & Tsiddon, 1993). Therefore they find that in the long run international growth rates will converge. The theory try to explain this phenomenon by claiming that there is something as a falling behind effect, and that the only way for a country to catch up is by increasing the level of human capital so it will improve its ability to assimilate foreign technology in its local production. Verspagen’s model includes two countries, North and South, which represents technologically developed and developing countries respectively. The technology gap between the two is: 𝐾𝑛 (2.3) 𝐾𝑠 where G denotes the technology gap, K denotes a country’s knowledge stock and n and s represents North and South respectively. By this can be deducted that if the knowledge stock converges in a scale 1:1, the technology level will become 0. The knowledge stock for the two countries is defined as: 𝐺 = 𝑙𝑛 𝐾̇𝑛 = 𝛽𝑛 𝐾𝑛 (2.4) 𝐾̇𝑠 = 𝛽𝑛 + 𝑆 (2.5) 𝐾𝑠 where β illustrates the exogenous growth in the knowledge stock as a cause of R&D. The dots above the Kvariables is a notation of time while S denotes the growth in the knowledge stock that happens because of a knowledge spill over from North with the assumption that North always will be the technological leader. One of Verspagen’s assumptions when he say that there is a risk for developing countries in falling behind is that some of these countries are not capable of utilising a knowledge spill over because of a low level of human capital. Therefore, there is a difference between the potential and the actual spill over. The common denominator in this is the country’s learning capability, which depends on an inner capability and the technological distance to the leading country. The distance because it is easier for a low productive country to adopt capital that is slightly more sophisticated than highly sophisticated capital. Thus, equation (3) can be specified as: 11 𝑆 = 𝑎𝐺𝑒 −𝐺/𝛿 (2.6) where the potential spill over rate (𝑎𝐺, 0 < 𝑎 ≤ 1) is proportional with the size of the techonology gap. The learning capability (𝑒 −𝐺/𝛿 , 𝛿 > 0) is a function of the country’s inner learning capability, δ, and the technological distance. To analyse the dynamic effects of the technology gap the equations above can be used. Equation (2)-(4) is implemented in equation (1) and 𝛽𝑛 − 𝛽𝑠 is noted as b to get the following equation: ̇𝑑 𝐾𝑛 𝐾̇𝑛 𝐾̇𝑠 = − = 𝑏 − 𝑎𝐺𝑒 −𝐺/𝛿 𝑑𝑡 𝐾𝑠 𝐾𝑛 𝐾𝑠 This is the mathematical foundation for the basic model illustrated in the following model: 𝐺= 𝑙𝑛 (2.7) On the y-axis G denotes the technology gap between the two countries, while 𝐺̇ on the x-axis denotes the growth rate in technology gap B is the difference in North and South’s technology growth factors, and s denotes the spill over effect. The equation for 𝐺̇ is as follows: 𝐺̇ = 𝑏 − 𝑠 B illustrates the difference in North and South’s technology growth factors, and s denotes the spill over effect. From this can be deduced that when the s curve is above B South will experience a catching up effect to North because 𝐺̇ is negative. On the opposite, if the s curve is below B South will fall behind economically. The two important points of the model is that the bigger the technology gap between South and North is, the harder it is for South to be able to catch up. This because the technology gap increases as long as the s curve is below B, illustrated by the arrows pointing right in the figure. Secondly, as soon as a point above B is reached 𝐺̇ is positive which means that the technology gap will decrease automatically. 12 2.1 Analysis In this part human capital’s influence on economic growth in Kenya will be analysed. Within the years since its independence Kenya’s resource of human capital has improved, and especially within the last decade it has been made one of the top priorities of the Kenyan government. This development has been mostly successful, and the World Economic Forum, despite the fact that Kenya has received a relatively low ranking in total, has stated the following about human capital in Kenya: Kenya’s innovative capacity is ranked an impressive 50th, with high company spending on R&D and good scientific research institutions that collaborate well with the business sector in research activities. Supporting this innovative potential is an educational system that – although educating a relatively small proportion of the population compared with most other countries – gets relatively good marks for quality (37th) as well as for onthe job-training (62nd). The high ranking in innovation capacity and quality in the educational system indicates that Kenya has a possible competitive advantage in education. In the following the two theories presented in the theoretical part will be used to analyse Kenya’s development. To be able to conduct the analysis there is a need for an economical and technological leader. The obvious choice would be the United States since it is the current global economic leader. The World Economic Forum’s Competitiveness Report (2012) shows that the United States is stated as being in stage 3 of development, which is the final stage where the countries are innovation driven. On the opposite Kenya is place in stage 1, being factor driven (World Economic Forum, 2012). 2.1.1 Solow In the following there will be an analysis based on Solow’s growth model with human capital. Besides depending on population growth and the investment levels Solow argues that human capital is a great contributor to growth. He argues with his model that constant increases in the educational level of a population will increase economic growth in the long run. Moreover, he argues that the further away from its steady state level a country is the greater the potential is. Therefore, Kenya’s investments in education will be compared to GDP levels. From the following figure Kenya and the United States’s expenditures on education from 1970 to 2011 is showed. 13 The figure shows that while the United States has lowered its expenditures on education as a share of GNI, Kenya has increased this. The United States went from spending 7.5 per cent of GNI on education in 1970 to a flat rate of 4.8 per cent from 1995 to 2011. In the same period Kenya went from spending 3.8 per cent of GNI on education to 5.9 per cent in 2011. It can be seen from the figure that with the introduction of the free enrolment in primary education the expenditures went up and then decreased again in 2007. According to Solow the development in Kenya’s investments in human capital through education has developed in a positive way during the period from 1970. This since the percentage of GNI spent on education has increased. According to Solow this increases economic growth in the long run. Looking at Kenya’s economic growth since 1963 the high growth rates from 1966 and 1971 indicates that Kenya has not yet reached its steady state level. Moreover, Kenya has experienced growth rates of 7-9 per cent in 1977, 1986 and 2007. That put together with the fact that Kenya is still a developing country advocates that Kenya is still far from reaching its steady state level. This, according to Solow, increases the potential and effects on the economy of increasing the educational level in Kenya. If this is the case the work 14 on educating people conducted by SYW is helping Kenya in its economic development. The fact that Kenya is spending more of GNI in relative terms than the United States, which also is closer to its steady state level, gives Kenya a good case regarding its catching up potential, which will be elaborated in the following analysis of Verspagen’s theory. However, all theories should always be supplemented by a critical and realistic view towards the use of them. An example is that the model is based on the relationship between capital, labour and output. However, in a developing country the demography and economic circumstances will often lead to a situation where there is an uneven relationship between capital and labour. In Kenya it can be argued that there is too little capital because of a low level of investments compared to the labour force which wring the relationship between the two. This is a problem when looking at e.g. equation (1.2) and on how much output the single worker can produce at a given amount of capital, since this ideal situation might not occur because of the lack of capital because of low investments in this. Also, a problem specific for a country in a situation like Kenya is that the Solow model with human capital deals with skilled labour but does not distinct between skilled employed and unemployed labour and does not deal with unemployment. The unemployment rate in Kenya is 40 per cent, and among youth it is 64 per cent (Sauder School of Business, 2011). Because the formal sector in Kenya is too small to host all the newly urbanised youth, this evidently ends up in unemployment. This is a problem since Kenya is in the situation of much skilled labour but a high unemployment rate (Ahn & Silvers, 2005; Central Intelligence Agency, 2012). One of the main problems when using universal economic models is that they are based on a row of assumptions that is not necessarily consistent with the real world. For instance neoclassical models like Solow’s are often too simplified to explain situations in the developing world because of market imperfections due to especially corruption. Moreover, more factors that affect a country’s growth prospects are not dealt with in the model. These are for instance deadly diseases such as malaria and AIDS which most likely are affecting growth levels too. In 2010 33.3 million people where living with HIV worldwide, most of them living in countries with low growth levels, especially sub-Saharan Africa (UNAIDS, 2010). UNAIDS (2010) argues that HIV/AIDS can affect economic growth negatively and can cause a bigger equality gap. In the Solow model it will be hard to conclude on a direct effect because AIDS, all other things being equal, will decrease saving rates since the households affected will have to work less and spend more on e.g. hospital bills, while a decrease in the population rate that follows with epidemics will have a positive effect. Moreover the incentive to invest in education and other human capital perspectives will decrease as the productivity will be likely to fall too (Ekhagen, 2009). However, the result are not so ambiguous in the model, as other studies like Bonnel (2000) what states that HIV/AIDS are destroying both growth and human capital and directly increases poverty. His study for the period 1990-1997 shows that HIV/AIDS reduced growth in Africa by 0.7 percentage points per year while malaria made up 0.3 percentage points (Bonnel, 2000). With the low growth rates already experienced in Kenya, this makes it hard to attain higher growth rates no matter how high the increases in human capital are. In addition to this Gyimah-Brempong (2002) finds that “A unit increase in corruption reduces the growth rates of GDP and per capita income by between 0.75 and 0.9 percentage points and between 0.39 and 0.41 percentage points per year respectively” (GyimahBrempong, 2002) . 15 2.1.1.1 Sub conclusion Looking at the specific situation in Kenya it can be seen that Kenya has increased its levels of education expenditures while the United States has lowered these. This means that Kenya now spend a larger share of GNI on education than the United States. At the same time Kenya gets a relatively good mark for the quality of its educational system. Moreover, growth rates indicate that Kenya is still far from its steady state level. However, despite the increase in the general expenditure level in the educational sector the average growth level in the period can be considered lower than expected in the light of the increased investments in human capital. The main reason why the growth rates in Kenya has not been higher despite the increased expenditure level in education is found to be the high level of unemployment. When the skilled labour is not actually on the labour market they do not bring the benefits that Solow predicts, because it is an infringement on the assumptions that the model it built on. Also, common diseases like HIV/AIDS and malaria affect the model and human capital’s effect on economic growth negatively. Therefore, although human capital is considered to have a positive effect on economic growth in Kenya, these mentioned factors decrease this effect. 2.1.2 Verspagen To conduct the analysis it needs to be proven that Kenya has a lower technological level and less investment in innovation than the United States. The World Economic Forum ranks the United States as number 14 over countries where the latest technologies are available, while Kenya is ranked as number 74. The number here is subjective, however, it is not the exact ranking that is the point of comparison but rather the fact that the United States is ranked well above Kenya. To determine who has the lowest amount of investments in innovation, the number of patens taken is being used. Here the United States is ranked as number 12 while Kenya is ranked as number 95 (World Economic Forum, 2012). This validates that the United States can be used as North in the analysis while Kenya can be used as South. Per capita growth rates are being used for the sake of comparison. 16 To see the trend more clearly it is useful to calculate a moving average for the period instead of looking at the year-to-year growth rates. This can be done since when looking at growth rates it is the long run trend that is important rather than coincidences for one year. Therefore, another figure is being used to conduct the analysis. 3 From the figure can be seen that in the period from 1963 to 1980 the development has been rather volatile with years of a falling behind effect followed by years of a catching up effect. In the years from 1968 to 1973 there has been a big catching up effect which was due to two years of impressive growth rates of 18 and 12 per cent in the years 1971 and 1972 respectively. From 1980 until 2003 Kenya has experienced a clear falling behind tendency with growth rates below the United States through during the entire period. From 2003, the year the Kenyan government introduced free primary education, and until 2012 Kenya has been catching up to the United States. This could indicate that Kenya has improved in using spill-over effects from the technologically leading countries. From the Figure 2 it can be seen that the expenditures relative to GNI in Kenya has increased compared to the United States, which may have had a positive influence on the knowledge stock in Kenya. Going back to the numbers on new technologies available and patents taken, these indicate that there is a large technology gap between Kenya and the United States which makes it hard for Kenya to catch up. This due to the fact that Kenya, if in point A at the beginning, will be moving further right without changing to a higher s curve. This situation is marked in the following figure by the arrows and the number 1. 3 The reason why a 3 year moving average has been used is that it flattens the curve and thereby enables a clearer trend, without removing too many years at the end of the period. 17 That Kenya has not been able to jump to a higher s-curve is due to the fact that it has not had the technological level to make use of spill overs from the more technologically advanced countries. That can be some of the reason why Kenya during its history has mostly been falling behind economically. Recent growth rates, however, indicates that the falling behind tendency is over and replaced by a situation where Kenya is catching up. This situation is marked by the arrows pointing up and the number 2 in the figure. If this is the case Kenya is likely to have been able to jump to higher s-curves because an increase in the educational level has enabled the country to make use of spill over effects. In this case, because Kenya is one of the largest receivers of foreign aid, some of this might be due to the fact that the aid agencies and international NGO’s brings with them more advanced technologies in their work. SYW, being an NGO supported by foreign aid agencies, thereby is likely to not just help raising the educational level but also bring in more advanced technologies introduced by the aid agencies. Also Verspagen’s model can, however, be criticised. It does not deal with e.g. the whole investment perspective and the practical implementation of its recommendations. It is rather black and white – make larger investments in education to catch up – but does not deal much with the fact that developing countries only have little economic resources. In many cases there are not financial means for long term investments like education. Instead, there is a focus on investments that show results on the short term. Moreover, factors like high inflation, high levels of corruption and high unemployment rates are all situations that are familiar characteristics to most developing countries, and also factors that discourage increasing investments in education. This both for the single individual and on state level. It is important that both actors can see that there is a potential for positive returns in the future. Otherwise spending time and money on education can seem discouraging. Despite the earlier mentioned high unemployment rate among the youth it can be argued that seen in the perspective of social sciences education is still a good investment since it affects other topics positively. The citizens will become more aware of the fact that they, through their right to vote, have the possibility of changing the society to the better. They will be able to question to whatever bad decisions the government are making and demand that the public spending will benefit them and their wishes. Thereby it strengthens civil society, makes the people less vulnerable and promotes vertical and citizen-led accountability towards the government, helping fight corruption (Action Aid, 2010). Also, it can be argued that the educational level affects all four indicators used to measure HDI, life expectancy, adult literacy rate, school enrolment and GDP. The literacy rate and school enrolment are obvious since these are directly linked with education. Life expectance can be affected both through the increased knowledge about deadly diseases, but also 18 through education on topics like hygiene and the importance of washing hands regularly and what kind of care babies need. GDP is also affected which was explained in the theoretical part. 2.1.2.1 Sub conclusion A moving average has been made to compare Kenya’s growth rates with the United States’. This shows that for most of the period from 1963 to 2003 Kenya has been falling behind economically to the United States. However, from 2003 this tendency has changed so that Kenya started developing a catching up effect instead. Why this is happened is hard to give an unambiguous answer to, but in this period the Kenyan government has made large improvements in the educational sector, which can make up some of the explanation. If this is the case Kenya has improved its learning capability which has made it more likely to benefit from spill overs from the world’s economic leaders. This provides a potential for Kenya to increase its growth rates and their distance to the United States even further in the future. The way this can be done is by continuing to improve human capital in Kenya till it reaches a level where the economy automatically benefits from spill over effects. However, also in this model unemployment is an obstacle as well as a small economic liberty of action in government spending. Moreover, in both models corruption is likely have a negative effect on the effectiveness of the models. 2.2 Discussion of the relationship between equality and economic growth Now back to the discussion from the introduction about the ideal: equality. In developed countries it is mostly the correlation between equality and growth that is discussed; if greater equality leads to lower growth rates. In developing countries the opposite correlation is more relevant; will higher growth rates lead to greater equality and including the question if economic growth itself promotes equality. However, these questions are hard to answer unambiguously and there are many different opinions about the subject. Belonging to the school saying that equality is positively related with growth are Alesina and Rodrick (1992) saying that: “In a democracy, the more unequal the distribution of wealth, the lower is the growth rate of the economy”. At the same time Persson and Tabellini (1991) makes a research to prove that inequality leads to slower growth. Research conducted by economist Gary Fields shows that economic growth will typically reduce poverty. However, if this will lead to greater equality or not depends on if the rich part of the societies is gaining more that the poor is. Simon Kuznets, with his u-shaped curve, argues instead that with economic progress equality will first decrease and then increase, this along with the movement of jobs from the agricultural sector towards the industrial sector (Kuznets, 1955). Meanwhile, Tilly (2004) finds that growth only will promote equality as long as policies and the institutional set up is able to help this development. A question is if the elite is really willing to go in front in a fight for greater equality. Kenya’s politicians are among the highest paid in the world even though Kenya also hosts some of the poorest people of the world. After a doubtful election in 2007 where Kibaki was re-elected privatizations has continued instead of using the government institutions’ revenue to create greater welfare. 19 Kristin Forbes (2000) is of the belief that inequality leads to growth, saying that: “On short and medium term an increase income inequality can boost economic growth”. To this Hongyi and Heng-fu (2002) says: “If public consumption enters the utility function income inequality may theoretically lead to higher economic growth”. However, these discussions are mainly made about developed countries and how the two factors are correlated there. In research focusing on developing countries the opposite correlation are most often used; if growth leads to either equality or inequality. Richard Adams Jr. (2004) finds economic growth an important tool to help increase equality among a country’s citizens. Roemer and Gugerty (1997) has conducted an empirical research finding that when there is economic growth, the poorest part of the population’s income increases with the same rate, thereby lessening inequality. This result is similar to Dollar and Kraay’s (2001) research from 2001 that shows that economic growth leads to increased equality since the poorest’s income rises at the same level as average incomes. Belonging to the opposite school is Forsyth (2000), stating that: “There is plenty of evidence that current patterns of growth and globalization are widening income disparities and thus acting as a brake on poverty reduction.”. To this Kassiola (1990) finds that because of competitive advantages rich will benefit more from increased growth rates. To complicate matters even more there are also a school for the people that believes that there is no direct correlation between equality and growth. One of the researchers saying that this is the case is Shin (1980), while Barro (2000) saying that there are some factors that could indicate that in developing countries inequality benefits growth while the opposite could assert in developed countries. However, he says that this does not explain global inequality. Ravallion (2001) ends his research saying that the matter needs a deep microeconomic empirical analysis for somebody to be able to say anything about the correlation, while Panizza (2002) says that if the methods used to find a correlation between the two factors in earlier studies are changed just a little bit, the results will change a lot. These very different results that many prominent scholars have found witness that it is a complex matter to explain the correlation. However, looking at the gini index measuring inequality in Kenya it can be seen that this has fallen from 57.5 in 1992 to 42.1 in 1994. After this it increased slightly to 42.5 in 1997 and to 47.7 in 2005 (World Databank, 2012). A total fall in the period from 1992 to 2005, however, with an inequality increase in the latest of the eight years. Moreover, the positive development seemingly has mostly improved the rural areas, and Nairobi still has 60 per cent of its citizens living in slums (Oxfam GB, 2009). It can be argued that an increase in human capital among the poor and marginalised will lead to greater social equality since empowering people make them more aware of their rights and enable them to have an opinion on different topics. Also, in a gender perspective, when women are aware of their rights and things like domestic violence is not accepted, people are more likely to object towards it. Therefore, seeing equality in a more social way, human capital is likely to increase equality. Thereby, without being able to give a clear conclusion if human capital, including the work of SYW, is helping increasing the economic equality in Kenya it can be argued that it is plausible that it is leading to greater social equality. 20 2.3 Critical discussion of NGO’s work It has been widely discussed if NGO’s are doing any difference in developmental work in Africa, and some even suggest that they harm development. One of the most prominent persons in front of the group against NGO’s work in Africa is Amutabi. In his work The NGO factor in Africa: The case of arrested development in Kenya, he argues that NGO’s are a colonial tool to exploit the countries and keep them underdeveloped. This stems from the fact that these are sponsored by Western aid agencies which is why he questions their neutrality. In his book he includes a case study made on the Rockefeller Foundation which he uses to illustrate his opinion of a paradox where NGO’s in Kenya are on the one hand acting as agents of development and on the other as agents of external dominance. The exploitation he finds is taking place is that NGO’s are linking local Kenyan communities to global economic and social movements in order for them to be exploited. Amutabi finds in his research of Kenyan NGO’s that only a few show actual results of genuine development, where he uses financing of higher education as one of the best ways of achieving this (Amubuti, 2006). Empirical observations at SYW show cases where Amutabi’s arguments can be both argued for and against. A good thing about SYW’s work is that it works directly with the poor when arranging forums of education on different topics. Then it is out dealing with the problems where they are, in the rural areas for instance, where a large proportion of the adult participants are illiterate and have to sign participants lists by giving their fingerprints. The women and youth are being taught in issues that affect them directly like their rights, how these have changed since the new constitution was established in 2010, gender based violence and women leadership as regards to the coming election in March 2013. The participants get a chance at the end of the forums to come up with questions that affects their daily lives. For instance a woman is getting a divorce from her husband and he is not willing to give her anything. This woman wants to know her rights and is taught what they are and how to move on (Samba, 2007; Action Aid, 2010). Moreover, where some NGO’s chose only to focus on groups with a great potential, there is a need too for NGO’s that focus on some of the more vulnerable groups that there might not be so much potential in but who, however, deserves to know basic things like her rights and how to vote to best get her interests met (Samba, 2007; SOS Children's Villages, 2012). In this way SYW makes a difference for some people that are not targeted by other developmental institutions. However, there are also problems that tally with Amutabi’s arguments on NGO’s leading back to the colonial power structure. It is a problem when a forum is arranged that too many people show up. If for instance 100 people has been invited there are sometimes showing up to 170 people up because the rumours have spread. The problem about this is that it reduces the quality of the education since it often means that the rooms booked to facilitate the arrangement are too small, that there is not enough water or that the rooms get too hot (Sauti Ya Wanawake, 2012c). Also, personal empirical observations have showed that a common problem is that some of the participants are only there because of the reimbursement they get to cover their transport. That means that they are mostly participating for the sake of the small amount of money they get and not for the benefit of the educational perspective. This is a problem because it means that the people who are actually there to learn get their learning experience degraded. Also, it can be argued that when this is the case a dependency pattern is created where the Western donors though local NGO’s are paying money to the local living in poverty. This is a problem similar to what Amutabi deals with but also a problem that is hard for both the aid agencies and the NGO’s to avoid and which is not the intention of their work (Samba, 2007; Action Aid, 2010). 21 Also, accountability and evaluation are important in order to see the results Amutabi is asking for. It can be hard to see the direct effects of the work SYW is doing since it is small steps that can only be evaluated subjectively with the people involved (Samba, 2007). While this is without a doubt really important it needs to be counterbalanced how this should be done since the work with aid agencies includes a lot of paper work already. It is seen as important that restrictions are being met but also that it does not end up in bureaucracy, where more time is being spent on filling in forms and photocopying everything for various agents, than what is actually being spent on dealing with and educating the women. This being said it can be fairly argued that even though Amitabi has some relevant points and are also right in some of them, the work of Kenyan NGO’s, hereunder SYW, should not be undervalued. It is valued in the small rural societies that they make up a priority for some even though they are not youth with a bright mind. The fact that the forums are well-visited, even though some people might mostly be in it for the money, and that there is an active debate between the participants asking questions and the facilitators answering and sharing their knowledge show that SYW makes a difference in the civil society (Sauti Ya Wanawake, 2012b). Moreover, it open up people’s minds to topics they have not considered before, like the fact that women can actually be leaders. In some of the evaluation interviews that have been done on women leadership the women said that before the forum they attended, they had not considered that women could be leaders (Sauti Ya Wanawake, 2012a). This is knowledge that they can pass on to their children, neighbours etc. and SYW’s messages can thereby reach an even bigger target group. 2.4 Are the findings universal? It cannot be recommended to make the results of this paper universal to all developing countries because of differences in the level of domestic security and conflicts, economic differences where some countries can be called growth miracles and others the opposite, great differences in levels of mortal diseases like malaria and AIDS, as well as large differences in the level of foreign aid the countries receive. Also, since growth rates are affected by many different factors that can vary among countries, these being for instance levels of corruption, political situation, level of received aid, security issues, mortality rates and inflation, it is recommended that an analysis like this in not directly used on other countries. Instead it should be adjusted to the specific time and space to get valid results. 22 2.5 Conclusion The issue that was dealt with in this paper is what influence improvements in human capital have on economic development, which is here measured by economic growth and economic equality. This issue was addressed through critical realism and in a belief that universal models can be used to find results in a specific time and space, her Kenya since its independence. The theories used were Solow’s growth model with human capital and Verspagen’s theory on catching up or falling behind. The Solow analysis showed that since Kenya has been investing in human capital compared to the United States simultaneously with being in a situation where it is far from its steady state level, there is a large potential for experiencing higher growth rates than it does. However, there are some obstacles that impede this development. These are mainly found to be a high unemployment rate among mainly the young people, as well as a wrenched relationship between the two production factors in the model, capital and labour. Moreover, many scholars argue that HIV/AIDS and malaria can affect the model in a negative way. The Verspagen analysis showed that from 1963 to 2003 Kenya has mainly been falling behind to the United States economically, but that this changed to a tendency of catching up from 2003 to 2010. However, it cannot be said unambiguously if was affected by the increase in the investments in the educational sector as well as the implementation of the Kenya’s Free Primary Education Policy in 2003. Also in this model unemployment is an obstacle for growth since it hinders Kenya from profiting from the increase in the country’s learning capability. With this it can be concluded that it is difficult to give an exact answer to the first part of the problem formulation, if increases in human capital has a positive influence on economic growth. This is due to the fact that growth is influenced by so many different factors in society, some of them being corruption, governance, internal and external conflicts, deadly diseases, inflation and unemployment. It can be seen from the figures presented in the paper that the economic growth since 2003 is higher than the ones of the United States. Meanwhile the two theories suggest that human capital increases growth. However, if the relatively higher growth rates in Kenya are due to increases in human capital or due to positive changes in one or more of the other factors cannot be seen directly from the analysis. For this an econometric analysis of values for the different parameters are needed. In the discussion on if human capital through increasing growth can have a positive influence on equality in Kenya no unambiguous answer were found. This due to the fact that there are prominent scholars both saying that there are a correlation between the two parameters and the opposite. Looking at the Gini index for Kenya it can be seen that over the period from 1992 to 2005 this has fallen which means that overall Kenya has become more equal though many people still live in slum areas. Also, the question should be looked at socially because it can be argued that increases in human capital empowers people and benefits all parameters of HDI. Therefore, the paper will end with a recommendation to the national, regional and international actors to keep investing in improving human capital. This, however, should be assisted by an effort to improve the other factors mentioned that affects GPD. Though the work of NGO’s, hereunder Sauti Ya Wanawake, and aid agencies can and should be seen in a critical view but at the same time is should be acknowledged that they are all working for the same agenda; to improve the conditions in the country they are working in. 23 2.6 Bibliografi Action Aid. (2010). People's action for just and democratic governance: Using evidence to establish accountability. Action Aid Denmark. Adams Jr., R. H. (2003). Economic growth, inequality and poverty: Findings from a new data set. The World Bank. Adams Jr., R. H. (Issue 12. Vol. 32 2004). Economic Growth, Inequality and Poverty: Estimating the Growth Elasticity of Poverty. World Development, p. 1989–2014. Ahn, A., & Silvers, J. (22. July 2005). Kenya: Free primary education brings over 1 million into school. Retrieved 5. November 2012 from http://reliefweb.int/report/kenya/kenya-free-primaryeducation-brings-over-1-million-school Alesina, A., & Rodrick, D. (1992). Distribution, political conflict, and economic growth: A simple theory and some empirical evidence. I A. e. Cukierman, Political Economy Growth & Business (s. 23-47). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Amubuti, M. N. (2006). The NGO factor in Africa: The case of arrested development in Africa. Routledge. Antoft et al. (2007). Håndværk og horisonter, tradition og nytænkning i kvalitativ metode. In A. e. al., Det kvalitative casestudium: introduktion til en forskningsstrategi (pp. 29-58). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. Barro, R. J. (Vol. 5 2000). Inequality and growth in a panel of countries. Journal of Economic Growth, p. 532. BBC News Africa. (2012). Retrieved 15. October 2012 from Kenya profile: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-13681341 Bonnel, R. (2000). HIV/AIDS: Does it Increase or Decrease Growth in Africa? . The World Bank. Brezis, E., Krugman, P., & Tsiddon, D. (No. 5. Vol. 83 1993). Leapfrogging in international competition: A theory of cycles in national technological leadership. The American Economic Review, p. 1211-1219. Central Intelligence Agency. (2012). Retrieved 15. October 2012 from The World Factbook: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ke.html de Vaus, D. (2007). Research design in social research. pp. 219-254: Sage publications. Dollar, D., & Kraay, A. (2001). Trade, growth and poverty. World Bank Publications. Duedahl, P., & Jakobsen, M. (2010). Introduktion til dokument analyse. Syddansk Universitetsforlag. Ekhagen, J. (2009). HIV/AIDS in economic growth models. Uppsala University. Forbes, K. J. (No. 4. Vol. 90 2000). A reassessment of the relationship between inequality and growth. The American Economic Review, p. 869-887. 24 Forsyth, J. (2000). Letter to the editor. The Economist. Glennie, J. (28. November 2011). Global inequality: tackling the elite 1% problem. Retrieved 5. November 2012 from The Guardian: http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/povertymatters/2011/nov/28/global-inequality-tackling-elite-national Global Humanitarian Assistance. (2011). GHA report 2011. Global Humanitarian Assistance. Gyimah-Brempong, K. (Issue 3. Vol. 3 2002). Corruption, economic growth, and income inequality in Africa. Economics of Governance, p. 183-209. Gyldendals åbne encyklopædi. (u.d.). Human capital. Retrieved 5. November 2012 from http://www.denstoredanske.dk/Samfund,_jura_og_politik/%C3%98konomi/Offentlig_og_kommun al_%C3%B8konomi,_forbruger%C3%B8konomi/human_capital Hongyi, L., & Heng-fu, Z. (Issue 3. Vol. 2 2002). Income Inequality is not Harmful for Growth: Theory and Evidence. Review of Development Economics, p. 318-334. Jones, C. I. (2002). Introduction to economic Growth. W.W. Norton & company. Kassiola, J. J. (1990). The death of industrial civilization: The limits to economic growth and the repoliticization of advanced industrial society. SUNY Press. Kuznets, p. (No. 1. Vol. 45 1955). Economic growth and income inequality. The American Economic Review. Langergaard et al. (2006). Viden, videnskab og virkelighed. Samfundslitteratur. Legovini, A. (2002). Kenya: Macro economic evolution since independence. UNDP. leksikon.org. (2012). Retrieved 15. October 2012 from Kenya: http://www.leksikon.org/art.php?n=3081 Lucas Jr., R. E. (No. 2. Vol. 61 1993). Making a miracle. Econometrica, p. 251-272. Oxfam GB. (2009). Urban poverty and vulnerability in Kenya. Panizza, U. (Vol. 7 2002). Income inequality and economic growth: Evidence from American data. Journal of Economic Growth, p. 25-41. Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (1991). Growth, distribution and politics. IMF Working Paper No. 91/78 . Ravallion, M. (Issue 11. Vol. 29 2001). Growth, inequality and poverty: Looking beyond averages. World Development, p. 1803–1815. Roemer, M., & Gugerty, M. K. (1997). Does economic growth reduce poverty? Harvard Institute for International Development. Samba, E. (2007). The role of reflection in women’s social change work. ActionAid International Kenya. 25 Samoff, J., & Carrol, B. (2003). From manpower planning to the knowledge era: World Bank policies on higher education in Africa. Prepared for the UNESCO Forum on Higher Education, Research and Knowledge. Sauder School of Business. (2011). Social entrepreneurship 101: Africa. Retrieved 12. November 2012 from http://www.africa.sauder.ubc.ca/library/2PageDescription.pdf Sauti Ya Wanawake. (2012a). Interview with Anne Gakie. Sauti Ya Wanawake. Sauti Ya Wanawake. (2012b). Interview with Susan Adhianbo. Sauti Ya Wanawake. Sauti Ya Wanawake. (2012c). Report of Likoni social auditors discussion forum. Sauti Ya Wanawake. Shin, D. C. (1980). Does rapid economic growth improve human lot? Some empirical evidence. D. Reidel Publishing Co. SOS Children's Villages. (2012). What we do. Retrieved 27. November 2012 from http://www.soschildrensvillages.org/What-we-do/Pages/default.aspx The Economist. (11. Marts 2004). More or less equal? Is economic inequality around the world getting better or worse? The Economist. Tilly, C. (2004). Why inequality is bad for the economy: Geese, golden eggs, and traps. Wealth Inequality Reader. UNAIDS. (2010). Report on the global AIDS epedemic. UNAIDS. UNICEF. (2011). Global inequality: Beyond the bottom billion. UNICEF. Verspagen, B. (No. 2. Vol. 2 1991). A new empirical approach to catching up or falling behind. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, p. 359-380. World Databank. (2012). World Databank. The World Bank. World Economic Forum. (2012). The global competitiveness report 2012-12013. Geneva: The World Economic Forum. 26