Program Guide for “Logical Fallacies” class (#5 of 6) Sunday 2-10-13

advertisement

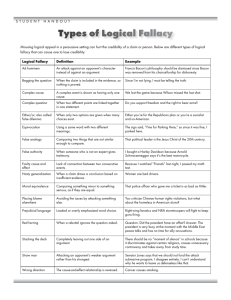

Program Guide for “Logical Fallacies” class (#5 of 6) Sunday 2-10-13 Agenda/timing (11:45 am – 1 pm): ------------------------------------------------------11:45-12:20 pm ------------------05 min. Introduction (people intro, religiously unbiased atmosphere, non-judgmental comments, chance for all to speak) 10 min. Review: What is the principle of charity (why it is important)? More on last week about “odds,” and two examples of logical fallacies in posters. 20 min. Presentation of four new logical fallacies 12:20-1:00 pm -----------------15 min. Small group discussion: come up with an example of each (regarding any subject; religion, politics, etc.) 25 min. Small group reports Bernie’s examples of what fellow atheists may say as logical fallacies (self-criticism). (Are these good examples? Feel free to disagree and discuss.) No true Scotsman: Making what could be called an appeal to purity as a way to dismiss relevant criticisms or flaws of an argument. This fallacy is often employed as a measure of last resort when a point has been lost. Seeing that a criticism is valid, yet not wanting to admit it, new criteria are invoked to dissociate oneself or one’s argument. Example from Antony Flew (an atheistic philosopher who later embraced theism in his old age): Imagine Alan McDonald, a Scotsman, sitting down with his Glasgow Morning Herald and seeing an article about how the "Brighton Sex Maniac Strikes Again". Alan is shocked and declares that "No Scotsman would do such a thing". The next day he sits down to read his Glasgow Morning Herald again; and, this time, finds an article about an Aberdeen man whose brutal actions make the Brighton sex maniac seem almost gentlemanly. This fact shows that Alan was wrong in his opinion but is he going to admit this? Not likely. This time he says, "No true Scotsman would do such a thing". Bernie’s example: How an atheist might use this fallacy: “Atheists are not militant nor violent. Stalin didn’t kill in the name of atheism, so his atheistic viewpoint is irrelevant to what he did.” Note: Stalin led a terror campaign against believers, and many other persecution programs and anti-religious propaganda. And he was an atheist. But no “true atheist” would do those things, right? Genetic: Judging something good or bad on the basis of where it comes from, or from whom it comes. To appeal to prejudices surrounding something’s origin is another red herring fallacy. This fallacy has the same function as an ad hominem, but applies instead to perceptions surrounding something’s source or context. Bernie’s example: How an atheist might use this fallacy: “Ken Ham (the creator of “The Creation Museum”) says macroevolution is false, but microevolution is true. Only Christians talk about macroevolution, so macroevolution is some made-up term by them, and is false. There’s no such thing as micro or macro evolution; there’s just evolution.” Real scientists do speak of macroevolution. (Sometimes creationists say true things ;-) Microevolution can refer to changes within a species in the gene pool; and macro evolution speaks of changes across species. It is like in the field of business, having micro and macro economics (micro economics might be sales at a particular McDonalds while macro economics might involve worldwide sales of all McDonalds). Black-or-white: Where two alternative states are presented as the only possibilities, when in fact more possibilities exist. Also known as the false dilemma, this insidious tactic has the appearance of forming a logical argument, but under closer scrutiny it becomes evident that there are more possibilities than the either/or choice that is presented. Bernie’s example: How an atheist might use this fallacy: “Either you believe in God, or you’re an atheist.” 1 Note: Some people are hard-core agnostics. They strongly believe that those who either believe in God, or disbelieve in God, are wrong; because they say it can’t be proven either way. Begging the question: A circular argument in which the conclusion is included in the premise. This logically incoherent argument often arises in situations where people have an assumption that is very ingrained, and therefore taken in their minds as a given. Circular reasoning is bad mostly because it’s not very good … (get it? ;-) A Christian claimed that atheists are using this fallacy when they say: “There is no God because we find no evidence of God in nature.” They say that evidence may turn-up. If you see a painting, but no painter, should you deduce there was no painter? Note: There’s more to do, than just the case of no evidence for God. There’s also a scientific case against God, if one is a young earth creationist or old earth creationist (most evangelical Christians). Also, Roman Catholic theology still states that all humans biologically descended from one human couple from which we inherited original sin; this has been disproven in science. Class Details INTRO QUESTIONS: 1. What is “the principle of charity,” and why is it important? 2. Illustration of “chances that we were born.” Discussion of cartoon 1 and cartoon 2. McMenamins Tavern & Pool 1716 NW 23rd Ave, Portland, OR (503) 227-0929 2 Google Map link: http://tinyurl.com/bxcrozf No True Scotsman No true Scotsman is an informal fallacy, an ad hoc attempt to retain an unreasoned assertion. When faced with a counterexample to a universal claim, rather than denying the counterexample or rejecting the original universal claim, this fallacy modifies the subject of the assertion to exclude the specific case or others like it by rhetoric, without reference to any specific objective rule. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_true_Scotsman Genetic Fallacy “Difficult as it may be, it is vitally important to separate argument sources and styles from argument content. In argument the medium is not the message.” Exposition: The Genetic Fallacy is the most general fallacy of irrelevancy involving the origins or history of an idea. It is fallacious to either endorse or condemn an idea based on its past—rather than on its present—merits or demerits, unless its past in some way affects its present value. For instance, the origin of evidence can be quite relevant to its evaluation, especially in historical investigations. The origin of testimony—whether first hand, hearsay, or rumor— carries weight in evaluating it. In contrast, the value of many scientific ideas can be objectively evaluated by established techniques, so that the origin or history of the idea is irrelevant to its value. For example, the chemist Kekulé claimed to have discovered the ring structure of the benzene molecule during a dream of a snake biting its own tail. While this fact is psychologically interesting, it is neither evidence for nor against the hypothesis that benzene has a ring structure, which had to be tested for correctness. So, the Genetic Fallacy is committed whenever an idea is evaluated based upon irrelevant history. To offer Kekulé's dream as evidence either for or against the benzene ring hypothesis would be to commit the Genetic Fallacy. Source: http://www.fallacyfiles.org/genefall.html Black-or-white fallacy Exposition: The problem with this fallacy is not formal, but is found in its disjunctive—"either-or"—premiss: an argument of this type is fallacious when its disjunctive premiss is fallaciously supported. Exposure: The Black-or-White Fallacy, like Begging the Question, is a validating form of argument. For example, some instances have the validating form: Simple Constructive Dilemma: Either p or q. If p then r. If q then r. Therefore, r. For this reason, this fallacy is sometimes called "false" or "bogus" dilemma. However, these names are misleading, since not all instances have the form of a dilemma; some instead take the following, also validating form: Disjunctive Syllogism: Either p or q. Not-p. Therefore, q. 3 Usually, the truth-value of premisses is not a question for logic, but for other sciences, or common sense. So, while an argument with a false premiss is unsound, it is usually not considered fallacious. However, when a disjunctive premiss is false for specifically logical reasons, or when the support for it is based upon a fallacy, then the argument commits the Black-or-White Fallacy. One such logical error is confusing contrary with contradictory propositions: of two contradictory propositions, exactly one will be true; but of two contrary propositions, at most one will be true, but both may be false. For example: Contradictories: It's hot today. It's not hot today. Contraries: It's hot today. It's cold today. A disjunction whose disjuncts are contradictories is an instance of the Law of Excluded Middle, so it is logically true. For instance, "either it's hot today or it's not hot today." In contrast, a disjunction whose disjuncts are contraries is logically contingent. For example, "either it's hot today or it's cold today." If an arguer confuses the latter with the former in the premiss of an argument, they commit the Black-or-White Fallacy. Analysis of the Example: Fatalism is not the alternative to superstition; it is an alternative. Superstition involves acting in ways that are ineffective, whereas fatalism involves failing to act even in situations in which our efforts can be effective. Fortunately, there are other alternatives, such as recognizing that there are some things we can control and other things we cannot, and only acting in the first case. Source: http://www.fallacyfiles.org/eitheror.html Begging the question Alias: -- Circular Argument -- Circulus in Probando -- Petitio Principii -- Vicious Circle Etymology: The phrase "begging the question", or "petitio principii" in Latin, refers to the "question" in a formal debate—that is, the issue being debated. In such a debate, one side may ask the other side to concede certain points in order to speed up the proceedings. To "beg" the question is to ask that the very point at issue be conceded, which is of course illegitimate. Misrule of Thumb: Begging the question is a fallacious form of argument. Therefore, to beg the question is to argue fallaciously. Form: Any form of argument in which the conclusion occurs as one of the premises, or a chain of arguments in which the final conclusion is a premise of one of the earlier arguments in the chain. More generally, an argument begs the question when it assumes any controversial point not conceded by the other side. Example: To cast abortion as a solely private moral question,…is to lose touch with common sense: How human beings treat one another is practically the definition of a public moral matter. Of course, there are many private aspects of human relations, but the question whether one human being should be allowed fatally to harm another is not one of them. Abortion is an inescapably public matter. 4 Analysis Exposition: Unlike most informal fallacies, Begging the Question is a validating form of argument. Moreover, if the premises of an instance of Begging the Question happen to be true, then the argument is sound. What is wrong, then, with Begging the Question? First of all, not all circular reasoning is fallacious. Suppose, for instance, that we argue that a number of propositions, p1, p2,…, pn are equivalent by arguing as follows (where "p => q" means that p implies q): p1 => p2 => … => pn => p1 Then we have clearly argued in a circle, but this is a standard form of argument in mathematics to show that a set of propositions are all equivalent to each other. So, when is it fallacious to argue in a circle? For an argument to have any epistemological or dialectical force, it must start from premises already known or believed by its audience, and proceed to a conclusion not known or believed. This, of course, rules out the worst cases of Begging the Question, when the conclusion is the very same proposition as the premise, since one cannot both believe and not believe the same thing. A viciously circular argument is one with a conclusion based ultimately upon that conclusion itself, and such arguments can never advance our knowledge. Q&A: Q: In Patrick J. Hurley's A Concise Introduction to Logic, (10th ed.) a True/False exercise is posed: "Arguments that commit the fallacy of begging the question are normally valid." Now there certainly are a few things wrong with this question, not the least of which is that Hurley breaks "begging the question" down into three sub-categories, though most sources I've come in contact with cite only "circular reasoning" as the primary example of "begging the question." But he states, "The first, and most common, way of committing this fallacy [of begging the question] is by leaving a possibly false key premise out of the argument while creating the illusion that nothing more is needed to establish the conclusion." He then gives an example, "Murder is morally wrong. This being the case, it follows that abortion is morally wrong." Here it seems to me that the example is an invalid argument. A key premise is missing, and thus the conclusion does not necessarily follow from the given premise. One might argue that the missing premise is implied, but if one accepts that then it seems the fallacy isn't an issue so much as the strength of the implied premise. After all, a valid argument is one in which if the premises are true, then it is impossible for the conclusion to be false. If there is only one premise and a second premise linking the first to the conclusion is missing, then it would be possible to have true premise(s) and a false conclusion, making the argument invalid. On this basis I answered "False" to the above question.―John Pocock A: I don't have the tenth edition of Hurley's text; the latest edition I own is the fifth, from 1994. In that edition, as well as earlier ones that I also have, he actually defines "begging the question" as a type of valid argument (p. 153). I think that this is a mistake, but it means that the question you answered "false" would be true by definition. Of course, this raises―not "begs"―the question whether the abortion argument is in fact an example of begging the question; if it's invalid, then it can't be an instance of begging the question. I think that it's a mistake to define "begging the question" as a type of valid argument because it's unnecessary, since all circular arguments are valid. As I mention in the Exposition above, begging the question is a validating form of argument. This sounds counter-intuitive, especially if you over-estimate the importance of validity. Validity is a virtue of arguments, but a good argument also needs to be sound. Moreover, as explained above, even soundness is not enough: a good argument must actually advance our knowledge or the debate we are in. Begging the question gets us nowhere, as we just end up going around in circles. Why is a circular argument necessarily valid? This surprising fact is a consequence of the definition of "valid": a valid argument is one in which the truth of the premises necessitates the truth of the conclusion. If the conclusion of an argument is one of its premises, then clearly the truth of its premises necessitates the truth of that conclusion. In the fifth edition, Hurley gives the same example and apparently considers "all abortions are murders" to be a suppressed premise of the argument. So, Hurley takes the complete argument to be: 5 -- Murder is morally wrong. -- All abortions are murders. (Suppressed) -- Therefore, abortion is morally wrong. This is certainly a valid argument. Moreover, it doesn't appear to be circular, since the conclusion is not one of the premises. Why, then, does it beg the question? It begs the question because the word "murder" is not a morally-neutral word, such as "killing". All murders are killings, but not all killings are murders. A person who kills someone in self-defense, a soldier who kills in battle, or a policeman who kills in the line of duty, is not a murderer. So, the first, unsuppressed premise is really unnecessary, as the argument is valid without it: All abortions are murders. Therefore, abortion is morally wrong. Or, to spell out what "murder" means: All abortions are wrongful killings. Therefore, abortion is morally wrong. Which is clearly circular and, therefore, valid. In the original argument, the moral wrongness of abortion has been smuggled into the premise via the morally loaded word "murder". This is how real-life questions are often begged, that is, by using loaded language to conceal the fact that an argument is circular. Exposure: The phrase "begs the question" has come to be used to mean "raises the question" or "suggests the question", as in "that begs the question" followed by the question supposedly begged. The following headlines are examples: Warm Weather Begs the Question: To Water or Not to Water Yard Plants Latest Internet Fracas Begs the Question: Who's Driving the Internet Bus? Hot Holiday Begs Big Question: Can the Party Continue? This is a confusing usage which is apparently based upon a literal misreading of the phrase "begs the question". It should be avoided, and must be distinguished from its use to refer to the fallacy. Reader Response: In your Etymological Fallacy "Exposition" section, you point out that "the meanings of words change over time." I state, with zero evidence beyond personal experience, that today most people use the phrase "begs the question" to mean "raises the question". I have found very few people who were aware of its "Petitio Principii" definition. When terms like "Circular Argument" are currently far more clear to the general population than "begs the question", why do you suggest that "begs the question" should cling to its older definition as opposed to being dropped for its current common usage? As I mentioned, I have no hard numerical evidence to back up my claim, but I believe the postulate would prove true if studied. I'm sure there would be variance between a Harvard Campus study vs. a ghetto study, but I believe the median American value would support it.―Dan Rotelli I think that you're right about the common use of the phrase "begs the question", and the newspaper headlines above are evidence that it usually has the meaning "raises the question" among editors and journalists. You also make a good point about the alternative name "circular argument", or "circular reasoning", for this fallacy. These are far better names than the traditional one, since they give an idea of the logical nature of the mistake, as well as being more memorable. "Begging the question" has always been a puzzling phrase: Why "beg"? What question? Moreover, "begging the question" is a poor translation of the Latin phrase "petitio principii"; a more accurate translation might be something like "requesting first principles". However, these are good arguments for dropping the phrase "begs the question" altogether, rather than using it to mean "raises the question". It's still a puzzling phrase when used in the common newspaper sense: why "beg" the question? Why should newspaper editors use "begs" instead of the available alternatives of "raises", "suggests", or "invites" the question? 6 At best, what started out as a misuse of logical jargon to impress the reader has turned into an idiom because neither the writer nor reader knew what the phrase meant. Perhaps saving the logical sense of "begs the question" for common use is a lost cause. However, it may not be a hopeless cause to get people to stop using the phrase at all. Analysis of the Example: This argument begs the question because it assumes that abortion involves one human being fatally harming another. However, those who argue that abortion is a private matter reject this very premise. In contrast, they believe that only one human being is involved in abortion—the woman—and it is, therefore, her private decision. 7 List of all fallacies, from: http://yourlogicalfallacyis.com/poster Strawman: Misrepresenting someone’s argument to make it easier to attack. By exaggerating, misrepresenting, or just completely fabricating someone's argument, it's much easier to present your own position as being reasonable, but this kind of dishonesty serves to undermine rational debate. False Cause: Presuming that a real or perceived relationship between things means that one is the cause of the other. Many people confuse correlation (things happening together or in sequence) for causation (that one thing actually causes the other to happen). Sometimes correlation is coincidental, or it may be attributable to a common cause. Appeal to emotion: Manipulating an emotional response in place of a valid or compelling argument. Appeals to emotion include appeals to fear, envy, hatred, pity, guilt, and more. Though a valid, and reasoned, argument may sometimes have an emotional aspect, one must be careful that emotion doesn’t obscure or replace reason. The fallacy fallacy: Presuming that because a claim has been poorly argued, or a fallacy has been made, that it is necessarily wrong. It is entirely possibly to make a claim that is false yet argue with logical coherency for that claim, just as is possible to make a claim that is true and justify it with various fallacies and poor arguments. Slippery slope: Asserting that if we allow A to happen, then Z will consequently happen too, therefore A should not happen. The problem with this reasoning is that it avoids engaging with the issue at hand, and instead shifts attention to baseless extreme hypotheticals. The merits of the original argument are then tainted by unsubstantiated conjecture. Ad hominem (Latin: “to the person”): Attacking your opponent’s character or personal traits in an attempt to undermine their argument. Ad hominem attacks can take the form of overtly attacking somebody, or casting doubt on their character. The result of an ad hominem attack can be to undermine someone without actually engaging with the substance of their argument. Tu quoque (Latin: ”You too”): Avoiding having to engage with criticism by turning it back on the accuser - answering criticism with criticism. Literally translating as ‘you too’ this fallacy is commonly employed as an effective red herring because it takes the heat off the accused having to defend themselves and shifts the focus back onto the accuser themselves. Personal incredulity: Saying that because one finds something difficult to understand, it’s therefore not true. Subjects such as biological evolution via the process of natural selection require a good amount of understanding before one is able to properly grasp them; this fallacy is usually used in place of that understanding. 8 Special pleading: Moving the goalposts or making up exceptions when a claim is shown to be false. Humans are funny creatures and have a foolish aversion to being wrong. Rather than appreciate the benefits of being able to change one’s mind through better understanding, many will invent ways to cling to old beliefs. Loaded question: Asking a question that has an assumption built into it so that it can’t be answered without appearing guilty. Loaded question fallacies are particularly effective at derailing rational debates because of their inflammatory nature - the recipient of the loaded question is compelled to defend themselves and may appear flustered or on the back foot. Burden of proof: Saying that the burden of proof lies not with the person making the claim, but with someone else to disprove. The burden of proof lies with someone who is making a claim, and is not upon anyone else to disprove. The inability, or disinclination, to disprove a claim does not make it valid (however we must always go by the best available evidence). Ambiguity: Using double meanings or ambiguities of language to mislead or misrepresent the truth. Politicians are often guilty of using ambiguity to mislead and will later point to how they were technically not outright lying if they come under scrutiny. It’s a particularly tricky and premeditated fallacy to commit. The gambler’s fallacy: Believing that ‘runs’ occur to statistically independent phenomena such as roulette wheel spins. This commonly believed fallacy can be said to have helped create a city in the desert of Nevada USA. Though the overall odds of a ‘big run’ happening may be low, each spin of the wheel is itself entirely independent from the last. Bandwagon: Appealing to popularity, or the fact that many people do something, as an attempted form of validation. The flaw in this argument is that the popularity of an idea has absolutely no bearing on its validity. If it did, then the Earth would have made itself flat for most of history to accommodate this popular belief. Appeal to authority: Saying that because an authority thinks something, it must therefore be true. It’s important to note that this fallacy should not be used to dismiss the claims of experts, or scientific consensus. Appeals to authority are not valid arguments, but nor is it reasonable to disregard the claims of experts who have a demonstrated depth of knowledge unless one has a similar level of understanding. Composition/division: Assuming that what’s true about one part of something has to be applied to all, or other, parts of it. Often when something is true for the part it does also apply to the whole, but because this isn’t always the case it can’t be presumed to be true. We must show evidence for why a consistency will exist. No true Scotsman: Making what could be called an appeal to purity as a way to dismiss relevant criticisms or flaws of an argument. This fallacy is often employed as a measure of last resort when a point has been lost. Seeing that a criticism is valid, yet not wanting to admit it, new criteria are invoked to dissociate oneself or one’s argument. 9 Genetic: Judging something good or bad on the basis of where it comes from, or from whom it comes. To appeal to prejudices surrounding something’s origin is another red herring fallacy. This fallacy has the same function as an ad hominem, but applies instead to perceptions surrounding something’s source or context. Black-or-white: Where two alternative states are presented as the only possibilities, when in fact more possibilities exist. Also known as the false dilemma, this insidious tactic has the appearance of forming a logical argument, but under closer scrutiny it becomes evident that there are more possibilities than the either/or choice that is presented. Begging the question: A circular argument in which the conclusion is included in the premise. This logically incoherent argument often arises in situations where people have an assumption that is very ingrained, and therefore taken in their minds as a given. Circular reasoning is bad mostly because it’s not very good … (get it? ;-) Appeal to nature: Making the argument that because something is ‘natural’ it is therefore valid, justified, inevitable, good, or ideal. Many ‘natural’ things are also considered ‘good’, and this can bias our thinking; but naturalness itself doesn’t make something good or bad. For instance murder could be seen as very natural, but that doesn’t mean it’s justifiable. Anecdotal: Using personal experience or an isolated example instead of a valid argument, especially to dismiss statistics. It’s often much easier for people to believe someone’s testimony as opposed to understanding variation across a continuum. Scientific and statistical measures are almost always more accurate than individual perceptions and experiences. The Texas sharpshooter: Cherry-picking data clusters to suit an argument, or finding a pattern to fit a presumption. This ‘false cause’ fallacy is coined after a marksman shooting at barns and then painting a bulls eye target around the spot where the most bullet holes appear. Clusters naturally appear by chance, and don’t necessarily indicate causation Middle ground: Saying that a compromise, or middle point, between two extremes must be the truth. Much of the time the truth does indeed lie between two extreme points, but this can bias our thinking: sometimes a thing is simply untrue and a compromise of it is also untrue. Half way between truth and a lie, is still a lie. 10