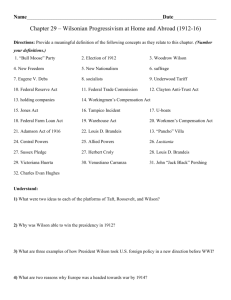

Woodrow Wilson

advertisement

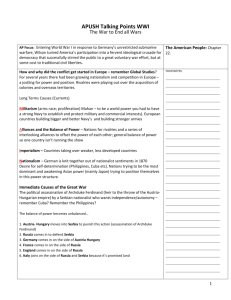

WOODROW WILSON – MORAL DIPLOMACY Woodrow Wilson and his secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan, came into office with little experience in foreign relations but with a determination to base their policy on moral principles rather than the selfish materialism that they believed had animated their predecessors' programs. Convinced that democracy was gaining strength throughout the world, they were eager to encourage the process. In 1916, the Democratic-controlled Congress promised the residents of the Philippine Islands independence; the next year, Puerto Rico achieved territorial status, and its residents became U.S. citizens. Working closely with Secretary of State Bryan, Wilson signed twenty-two bilateral treaties which agreed to cooling-off periods and outside fact-finding commissions as alternatives to war. In a statement issued soon after taking office, Wilson declared that the United States hoped "to cultivate the friendship and deserve the confidence" of the Latin American states, but he also emphasized that he believed "just government" must rest "upon the consent of the governed." Latin Americans were delighted by the prospect of being free to conduct their own affairs without American interference, but Wilson's insistence that their governments must be democratic undermined the promise of self-determination. In 1915, Wilson responded to chronic revolution in Haiti by sending in American marines to restore order, and he did the same in the Dominican Republic in 1916. The military occupations that followed failed to create the democratic states that were their main objective. In 1916, Wilson practiced an old-fashioned form of imperialism by buying the Virgin Islands from their colonial master, Denmark, for $25 million. Aggressive Moral Diplomacy Mexico posed a special problem for Wilsonian diplomacy. Having been in revolution since 1899, Mexico, in 1913, came under the rule of the counterrevolutionary General Victoriano Huerta, who clamped a bloody authoritarian rule on the country. Most European nations welcomed the order and friendly climate for foreign investments that Huerta offered, but Wilson refused to recognize "a government of butchers" that obviously did not reflect the wishes of the Mexican people. His stance encouraged anti-Huerta forces in northern Mexico led by Venustiano Carranza. In April of 1914, Mexican officials in Tampico arrested a few American sailors who blundered into a prohibited area, and Wilson used the incident to justify ordering the U.S. Navy to occupy the port city of Veracruz. The move greatly weakened Huerta's control, and he abandoned power to Carranza, whom Wilson immediately recognized as the de facto president of Mexico. One of Carranza's rivals, Pancho Villa, moved to provoke a war between the Carranza government and the United States by crossing the border into New Mexico on March 9, 1916, and killing several Americans. Wilson, without securing permission from Carranza, sent an expedition of 7,000 U.S. soldiers commanded by General John "Black Jack" Pershing into Mexico in pursuit of Villa. The expedition failed to capture Villa but provoked a confrontation between the Americans and Carranza's forces in which men on both sides were killed and several Americans were captured. Alarmed by the danger of war, Wilson reaffirmed his commitment to Mexican self-determination and agreed to discuss methods of securing the border area with the Mexican government. Early in 1917, when it began to appear that the United States could not avoid being dragged into the European war, Wilson withdrew all U.S. forces from Mexico. The decision coincided with the publication of an intercepted message from Arthur Zimmermann in the German foreign office to the German minister in Mexico, instructing him to propose an alliance with Mexico against the United States if Germany and the United States went to war. Following an American defeat, Mexico would regain New Mexico, Texas, Arizona, and California, which had been ceded to the United States after the Mexican War in 1848. Wilson's release of the "Zimmermann Telegram" solidified U.S. public opinion against Germany, though Mexico was never tempted to accept the German proposal. Neutrality in World War I With the outbreak of fighting in the "Great War" in Europe in August 1914, President Wilson appealed to Americans to remain strictly neutral. He believed that the underlying cause of the war, which would leave 14 million Europeans dead by 1917, was the militant nationalism of the major European powers, as well as the ethnic hatreds that existed in much of Central and Eastern Europe. The conflict lined up the Central Powers—Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey, and Bulgaria—on one side, against the Allied Powers—initially Great Britain, France, Russia, and Serbia, and later Italy, Japan, Portugal, certain Latin American nations, China, and Greece—on the other. It started with the assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary by a young Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo in June 1914. This incident triggered an explosion of demands and counterdemands. Within months, a complex set of entangling and secret treaties and alliances engulfed much of the world—due to the imperial holdings of Germany, France, and England—in war. With nearly one in every seven Americans having been born in the countries at war, Wilson believed the United States must remain neutral. Because the American economy was in a recession when the war began, however, and the British and French were eager to buy American products, the administration interpreted neutral duties in ways that tended to favor the Allies. When Germany retaliated by using submarines to blockade the British Isles, Wilson refused to ban U.S. travel on British or American passenger ships or to cut off arms sales to the warring nations, as the Germans demanded. End of Neutrality In May 1915, a German submarine—called a "U-boat," which was a relatively fragile vessels that depended on surprise attacks from below the surface for its success—torpedoed the British liner Lusitania off the coast of Ireland, killing nearly 1,200 people, including 128 Americans. Wilson urged patience but demanded that Germany either halt or drastically curtail submarine warfare. Convinced that the President's policy would lead to an unnecessary war, Secretary Bryan resigned in June 1915. For a time, German concessions preserved peace, but Britain refused to abandon its blockade of Europe, and early in 1917, Germany resumed its submarine warfare. The Germans calculated that the move would force the United States into the war but not before they could mount a massive attack on Allied forces while destroying the British navy. After several American ships were sunk and the public release of the Zimmermann telegram outraged Americans, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. The Senate voted 82 to 6 to declare war on April 4, 1917; the House concurred on April 6 by a vote of 373 to 50. Jeannette Rankin of Montana, the first woman to serve in the House of Representatives, was among those who voted against the war. Wilson's war message condemned German U-boat attacks as "warfare against mankind" but emphasized that the main goal of the war should be to end militarism and make the world "safe for Democracy," not merely to defend American ships. He promised that the United States would fight to ensure democracy, self-government, the rights and liberties of small nations, and an international peace organization that would end war forever.