The Exclusionary Rule - Your Missouri Lawyers

advertisement

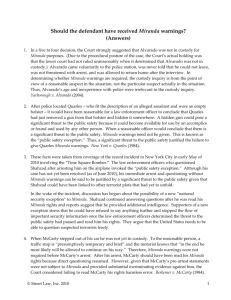

The Fifth Amendment and Other Considerations Landmark Cases Be sure to go to the Miranda v. Arizona case at http://landmarkcases.org. The materials contain a primer on Miranda, which I relied heavily on to prepare this presentation. The Exclusionary Rule • In Weeks v. United States, (1914), the Court unanimously held that the warrantless seizure of items from a private residence constitutes a violation of the Fourth Amendment. It also prevented local officers from securing evidence by means prohibited under the federal exclusionary rule and giving it to their federal colleagues. Weeks applied only to federal courts and federal law enforcement officials. • It was not until the case of Mapp v. Ohio, (1961), that the exclusionary rule was deemed to apply to state courts as well. • Applies to 5th Amendment violations also i.e. Miranda. Fruit of the poisonous tree A companion to the exclusionary rule is the "fruit of the poisonous tree" doctrine. Under this doctrine, a court may exclude from trial not only evidence that itself was seized in violation of the Constitution but also any other evidence that is derived from an illegal search. For example, suppose a defendant is arrested for kidnapping and later confesses to the crime. If a court subsequently declares that the arrest was unconstitutional, the confession will also be deemed tainted and ruled inadmissible at any prosecution of the defendant on the kidnapping charge. (Findlaw) The Exclusionary Rule may be the single best evidence of why the United States Constitution’s underlying purpose is limited government and why the U.S. government is truly created “by the people and for the people.” For sure, the rights of the individual are supreme over public safety when the rule is applied. --Millie Aulbur Some exceptions have arisen • Inevitable discovery. • The search or arrest warrant was not found to be valid based on probable cause, but was executed by government agents in good faith (called the good-faith exception). The Fifth Amendment No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation. Miranda v. Arizona (1966) • 50th Anniversary An accused person has the these rights when he is in police custody: • He has the right to remain silent, • Anything he says can and will be used against him in a court of law, • He has the right to the presence of an attorney, and • If he cannot afford an attorney one will be appointed for him prior to any questioning if he so desires. The Sixth Amendment In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense. Fifth Amendment Rationale for the Exclusionary Rule • To avoid the risk that statements were forced in violation of the defendant's Fifth Amendment rights; • To encourage officers to comply with the Miranda rules, thereby lessening the future likelihood of compelled selfincrimination; and • To discourage any police practices that tended to compel confessions from suspects. “Custody” controversy “Two discrete inquiries are essential to the determination: first, what were the circumstances surrounding the interrogation; and second, given those circumstances, would a reasonable person have felt he or she was at liberty to terminate the interrogation and leave. Once the scene is set and the players’ lines and actions are reconstructed, the court must apply an objective test to resolve the ultimate inquiry: was there a formal arrest or restraint on freedom of movement of the degree associated with formal arrest.” Thompson v. Keohane (1995) Custody controversy • Custody requires a significant deprivation of liberty. • A person is in custody only if they are subjected to either formal arrest or its “functional equivalent.” • Formal arrest—occurs when a person is explicitly told they are being placed under arrest or is booked at the stationhouse. • Functional equivalent—occurs when a suspect's freedom of action is significantly curtailed to a degree associated with a formal arrest. • Consider a reasonable person under the same conditions of the suspect: • Would a reasonable person under the same circumstances believe they were free to leave? (In other words: what would an average or typical member of the community think under the same circumstances?) • The Court is not trying to figure out what this particular suspect thought. Thompson v. Keohane (1995) • In September 1986, the body of a dead woman was discovered by two hunters in Fairbanks, Alaska. The woman had been stabbed 29 times. To gain assistance identifying the body, the police issued a press release with a description of the woman. Carl Thompson called the police station and identified the body as Dixie Thompson, his former wife. The police asked Thompson to come into the station under the pretense of identifying personal items found with the body, but it was the intention of the police to question Thompson about the murder.[ • Thompson came to the police station and was questioned for two hours. Two plainclothes officers performed the interrogation in an interview room. Thompson was not read his Miranda rights and throughout the interrogation he was told that he was free to leave.[6] The police told Thompson that they knew he killed his former wife and eventually Thompson confessed to the murder. Thompson was allowed to leave the police station, but then was arrested shortly thereafter. Dickerson v. United States (2000) “However, as time went on, the Supreme Court recognized that the Fifth Amendment was an independent source of protection for statements made by criminal defendants in the course of police interrogation. ‘In Miranda, we noted that the advent of modern custodial police interrogation brought with it an increased concern about confessions obtained by coercion." Custodial police interrogation by its very nature "isolates and pressures the individual”’ so that he might eventually be worn down and confess to crimes he did not commit in order to end the ordeal. In Miranda, the Court had adopted the now-famous four warnings to protect against this particular evil.” Dickerson v. United States (2000) Dissenting, Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, blasted the Court's ruling, writing that the majority opinion gave needless protection to "foolish (but not compelled) confessions." Yarborough v. Alvarado (2004) Alvarado is a 17 year old high school student. A police detective contacted his mother who agreed to bring him to the police station for questioning about a recent crime. When Alvarado arrived with his parents, the detective denied the parents’ request to remain with their son during the interview. While the parents waited in the lobby, Alvarado was questioned by police. He was not advised of his Miranda rights. During the two hour session, the detective twice asked Alvarado if he wanted to take a break. Alvarado admitted to his role in a murder and robbery that police were investigating. At the end of the interview Alvarado went home. His confession was offered as evidence against him at trial. Yarborough v. Alvarado (2004) In a five to four decision, the Court strongly suggested that Alvarado was not in custody for Miranda purposes. Alvarado came voluntarily to the police station, was never told that he could not leave, was not threatened with arrest, and was allowed to return home after the interview. In determining whether Miranda warnings are required, the custody inquiry is from the point of view of a reasonable suspect in the situation, not the particular suspect actually in the situation. Thus, Alvarado’s age and inexperience with police were irrelevant in the custody inquiry. Public safety exception to Miranda • The Public Safety Exception to Miranda • The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that Miranda warnings are unnecessary prior to questioning that is “reasonably prompted by a concern for the public safety” • Consider whether a reasonable officer in the same position would conclude that there is a significant threat to the public safety • Example: interrogation that occurs as police try to locate a bomb they believe is set to go off New York v. Quarles (1984) After receiving the description of an alleged assailant, a police officer entered a supermarket, and spotted Quarles, a man fitting the description. The officer ordered Quarles to stop. Quarles complied and was then frisked by the officer. Upon detecting an empty shoulder holster, the officer asked Quarles where his gun was. Quarles responded. The officer then formally arrested Quarles and read him his Miranda rights. Both the gun and Quarles initial response were offered as evidence against him at trial. New York v. Quarles (1984) After police located Quarles – who fit the description of an alleged assailant and wore an empty holster – it would have been reasonable for a law enforcement officer to conclude that Quarles had just removed a gun from that holster and hidden it somewhere. A hidden gun could pose a significant threat to the public safety because it could become available for use by an accomplice or found and used by any other person. When a reasonable officer would conclude that there is a significant threat to the public safety, Miranda warnings need not be given. This is known as the “public safety exception.” Thus, a significant threat to the public safety justified the failure to give Quarles Miranda warnings. (5-4 decision) Parting thought The Exclusionary Rule may be the single best evidence of why the United States Constitution’s underlying purpose is limited government and why the U.S. government is truly created “by the people and for the people.” For sure, the rights of the individual are supreme over public safety when the rule is applied. --Millie Aulbur