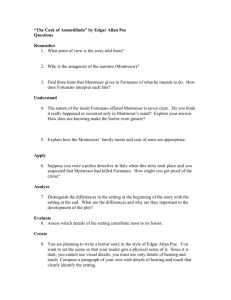

Tatum Keeley Tatum Ms. Tatum English III 15 November 2012 The

advertisement

Tatum 1 Keeley Tatum Ms. Tatum English III 15 November 2012 The Inevitable Fall of Pride Pride in oneself is certainly important; however, too much pride in oneself can be a problem. How far should one go to protect their pride? Montresor and Fortunato, two of Edgar Allen Poe’s characters, take their sense of pride to extremities beyond reason. Their actions beg the question: How far is too far? Poe takes his audience into a dark chasm of murderous sacrifice and moral self-sacrifice to illuminate the dangerous trap where followers of vain pride can become imprisoned. In his short story “The Cask of Amontillado,” Poe demonstrates the dangers of pride through the characterization of Fortunato and Montresor. From the very beginning of the story, Poe creates Fortunato to be extremely foolish through his behavior and his appearance. The first time Fortunato is even mentioned to the audience, he is described as wearing a “tight- fitting parti-striped dress” and having his head “surmounted by the conical cap and bells” (169). Immediately, Fortunato is visualized as foolish because he is literally dressed like a clown. Not only is his outfit ridiculous, but he is also revealed to be quite intoxicated. Fortunato’s eyes were “two filmy orbs that distilled the rheum of intoxication” (170). Montresor says, “He accosted me with excessive warmth, for he had been drinking much” (169). When Montresor tells him he found some Amontillado, Fortunato foolishly and drunkenly repeats himself three times. He says “Amontillado!” over and over again which verifies for the reader that he is indeed intoxicated and behaving rather foolishly (169). The last bit of evidence that suggests Poe’s Tatum 2 intention in establishing Fortunato as a foolish character is revealed in how easy it is for Montresor to manipulate him into coming with him to his wine vaults. Fortunato mindlessly follows him without any questions. Montresor simply feeds his ego and then plays off Fortunato’s own insecurities by mentioning how “some fools will have it that [Luchesi’s] taste is a match for [his] own” (169). Fotunato takes offense to this comment and quickly insists that he and Montresor go to his vaults to settle the matter once and for all. His behavior and appearance both support the interpretation that the reader should consider Fortunato foolish. Since Fortunato is established as foolish, the reader can infer that his blatant pride should also be deemed foolish. Fortunato consistently speaks very arrogantly to Montresor. For instance, when Montresor makes the statement that Luchesi’s taste for wine is comparable to Fortunato’s, he retorts that Luchesi “cannot tell Amontillado from Sherry” (169). Later he goes as far as to call Luchesi an “ignoramus” (172). Furthermore, Montresor sadistically asks Fortunato if he would like to turn around three different times in the story on account of his vaults being “insufferably damp” (169); however, Fortunato’s pride prevents him from heeding Montresor’s advice and he refuses each time. Even when Montresor has chained Fortunato up with shackles, Fortunato holds on to his pride (172). He doesn’t even beg for mercy as he realizes that his death is surely inevitable. In fact, he laughs and attempts to manipulate Montresor to free him by saying, …a very good joke indeed—an excellent jest. We will have many a rich laugh about it at the palazzo…over our wine…He! he! he!—he! he! he!—yes, the Amontillado. But is it not getting late? Will they be awaiting us at the palazzo, the lady Fortunato and the rest? Let us be gone. (173) Tatum 3 This manipulation, of course, is to no avail. Fortunato does not make another single attempt to convince his captor to free him. He simply refuses to answer and the last sound Montresor and the reader hear from him is “only a jingling of [his] bells” (173). He dies foolishly with his pride in tact. Due to his foolish pride, Fortunate suffers a gruesome death that could have been completely avoided. If he had not been so foolish and not let his pride consume him, Fortunato might have realized his forthcoming doom and prevented his own death. Instead, Montresor effortlessly chains him up. He describes the process as being only “the work of a few seconds” (172). As Montresor begins his task of erecting the tier that will create Fortunato’s tomb, the reader is left to dwell on the slow an agonizing death Fortunato will surely suffer. After all, Fortuanto’s “intoxication…had in a great measure worn off” (172). He was left to think about his stupidity and his prideful actions in a completely sober state of mind. How would he die? Would he die from the damp elements; from starvation; from dehydration; or maybe from absolute terror? It is impossible for the reader to say, which is maybe Poe’s point in creating such a terrifying scene. The reader can infer that one cannot imagine the position they put themselves in when they allow pride to control their actions. Fortunato is not the only character revealed to be prideful through; Poe reveals Montresor to be just as prideful. Montresor’s pride leads to dangerous consequences as well. Although Montresor is certainly not depicted as foolish, he is just as controlled by pride as his prisoner. Montresor, because of his pride, allows himself to be transformed into something evil and twisted. He “felt satisfied” about what he had done to Fortunato (173). His pride in his name is what drives Montresor crazy. This idea is subtly revealed to the reader when Montresor tells Fortunato his family’s motto. Montresor’s motto is “Nemo Tatum 4 me inpune lacessit” which translates to “No one dare attack me with impunity” (171). This is reminiscent of the beginning of the story when Montresor “vow[s] revenge” and to punish Fortunato with impunity (168). Obviously, the implication is that Fortunato has insulted his family’s name. The end of the story reveals Montresor to be just as bad off as Fortunato because he has been reduced to a psychopath. He feels absolutely no sympathy for Fortunato, which demonstrates his absolute transformation into an evil and twisted shell of a human being. His final words to the reader solidify this transformation when he mentions how “his heart grew sick—on account of the dampness of the catacombs” (173). His heart does not sympathize in any way with the poor soul that he has left to suffer and die in a damp tomb; his heart merely “grew sick” because he was cold in the vault. Edgar Allen Poe’s tale is a dark reminder of the terrible and dangerous consequences that can arise from incontrollable pride. Through his characters Montresor and Fortunato, the reader can see these consequences come to life and subsequently die in a dark pit of despair. Pride in oneself has the power to foolishly blind or frighteningly demoralize a person. Furthermore, the reader is left not knowing or understanding why Montresor is torturing Fortunato in the first place. What did this man even do? The fact that Fortunato’s fault was never revealed in the story brings forth a lingering question for the reader: Was all of this worth it? It is safe to assume that Poe believes pride is never worth the inevitable consequences it brings. Tatum 5 Works Cited Poe, Edgar Allen. “The Cask of Amontillado.” A Little Literature: Reading, Writing, Argument. Eds. Sylvan Barnet, William Burto, and William E. Cain. New York: Pearson, 2007. 168-173. Print.