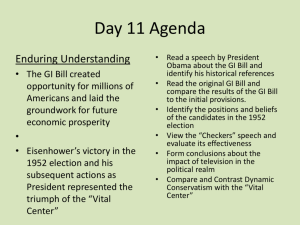

Candidate information

advertisement

Living Room Candidate Introduction: "The idea that you can merchandise candidates for high office like breakfast cereal is the ultimate indignity to the democratic process." -Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson, 1956 "Television is no gimmick, and nobody will ever be elected to major office again without presenting themselves well on it." -Television producer and Nixon campaign consultant Roger Ailes, 1968 In a media-saturated environment in which news, opinions, and entertainment surround us all day on our television sets, computers, and cell phones, the television commercial remains the one area where presidential candidates have complete control over their images. Television commercials use all the tools of fiction filmmaking, including script, visuals, editing, and performance, to distill a candidate's major campaign themes into a few powerful images. Ads elicit emotional reactions, inspiring support for a candidate or raising doubts about his opponent. While commercials reflect the styles and techniques of the times in which they were made, the fundamental strategies and messages have tended to remain the same over the years. The Living Room Candidate contains more than 300 commercials, from every presidential election since 1952, when Madison Avenue advertising executive Rosser Reeves convinced Dwight Eisenhower that short ads played during such popular TV programs as I Love Lucy would reach more voters than any other form of advertising. This innovation had a permanent effect on the way presidential campaigns are run. 1952: President Harry S. Truman entered 1952 with his popularity plummeting. The Korean War was dragging into its third year, Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist crusade was stirring public fears of an encroaching "Red Menace," and the disclosure of widespread corruption among federal employees rocked the administration. After losing the New Hampshire primary to Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver, who had chaired a nationally televised investigation of organized crime in 1951, President Truman announced on March 29, 1952, that he would not seek re-election. Truman threw his support behind Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson, who repeatedly declined to run but was eventually drafted as the Democratic nominee on the strength of his eloquent keynote speech at the convention. Stevenson proved to be no match for the Republican nominee, war hero Dwight D. Eisenhower, who played a key role in planning the Allied victory in World War II. A poll in March 1952 found Eisenhower the most admired living American, and in November he won a landslide victory on the basis of his pledge to clean up "the mess in Washington" and end the Korean War. Eisenhower: Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower for President Richard Nixon for vice president "It’s Time for a Change" In 1952, there was no precedent in presidential elections for the use of television "spot" advertising—short commercials that generally run between twenty seconds and a minute. Governor Thomas Dewey, declaring spots "undignified," rejected their use in his 1948 presidential campaign. In 1952, most campaign strategists preferred thirty-minute blocks of television time for the broadcast of campaign speeches. What distinguished Eisenhower’s campaign from Stevenson’s was that it relied more on spot ads than on speeches. The campaign pioneered their use with a series of ads titled "Eisenhower Answers America." The idea for the spots came from Madison Avenue advertising executive Rosser Reeves, who had created the M&M "melts in your mouth, not in your hands" campaign. Reeves convinced Eisenhower that spot ads placed immediately before or after such popular TV programs as I Love Lucy would reach more viewers, and at a much lower cost, than half-hour speeches. In each of the simple, twenty-second spots, Eisenhower responded to a question from an "ordinary citizen." The questioners—tourists enlisted near Radio City Music Hall—were photographed looking up, as though gazing at a hero. Eisenhower’s folksy responses, which he read from large cue cards, were used to create forty commercials, all filmed in one day in a Manhattan studio. The spots were designed to establish Eisenhower as a plain-speaking man in touch with the people. They repeatedly focused on three issues cited by polls as the voters’ main concerns: the Korean War, corruption in government, and the high cost of living. Stevenson: Democrat Adlai Stevenson for president John Sparkman for vice president "You Never Had It So Good" Speaking about the role of television advertising in election campaigns, Adlai Stevenson said, "I think the American people will be shocked by such contempt for their intelligence. This isn’t Ivory Soap versus Palmolive." Stevenson aide George Ball bitterly predicted that "presidential campaigns will eventually have professional actors as candidates." Stevenson based his television strategy on a series of eighteen half-hour speeches that aired on Tuesday and Thursday nights at 10:30. The goal was to take advantage of Stevenson’s oratorical skills and build his national recognition by developing a regular audience for the broadcasts. But the lateness of the time slot cut down on the number of potential viewers, and the actual audience consisted largely of people already predisposed to vote for Stevenson. Stevenson’s spot ads were little more than illustrated radio spots. The crude visuals generally consisted of a single shot, such as the simple cartoon drawing that illustrates the Ike and Bob ad, which implied that an Eisenhower presidency would be under the control of conservative Republican Robert Taft. Rather than defend the Truman administration, the ads attempted to distance Stevenson from it. Several of them reminded voters of how bad things were during the Depression, presided over by the last Republican president, Herbert Hoover. Stevenson never warmed up to the medium during the campaign. He refused to appear in his own spots, and his speeches, which were aired live, frequently ran too long; the broadcast would fade out while he was still talking. In his election-eve special, when his son tells him, "I like watching television better than being on it," Stevenson replies, "I guess that goes for all of us, doesn’t it?"