van manen ch. 9

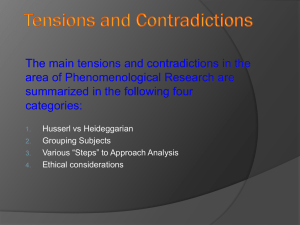

advertisement

van Manen (2014) Chapter 9; The Vocative EDCP 585 Vocative as Speaking from Somewhere to Someone • The experiential writing of the text should aim to create a sense of resonance in the reader. Resonance means that the reader recognizes the plausibility of an experience even if he or she has never personally experienced this particular moment or this kind of event. • When we speak we tend to stop listening to the object about which we speak. And now this object has lost its addressive and enigmatic power. Something can only speak to us if it is listened to, if we can be addressed by it. • The vocative aspects of phenomenology involve an aesthetic imperative a poetizing form of writing. Factual vs. Fictional: “truth value” • “The important point for phenomenological inquiry is that it does not matter whether the story is factual or fictional. Any factual empirical account of an experience immediately transfigures into the status of a fictional account when it is examined by phenomenological reflection of the reduction. Or, better, it does not help to make the distinction between factual empirical accounts and fictional or imagined empirical accounts. The only requirement is that the experiential account is plausible in its truth-value.” Phenomenology and the Empirical • …phenomenology … does not make empirical claims. [It] does not generalize from an empirical sample to a certain population, nor draw factual conclusions about certain states of affairs, happenings, or factual events. • …the data for phenomenological reflection are fictionalized or fictitious. Even so-called empirical data are treated as fiction since they are not used for empirical generalization or for making factual claims about certain phenomena or events. …phenomenological research does not aim for and does not permit empirical generalizations. • …fictionalizing a factual, empirical, or an already fictional account in order to arrive at a more plausible description of a possible human experience. Possible Resources for Phenomenology • “Fictional” examples may be drawn from literature and the arts: • mythology, poetry, biography, paintings, cinematography, and other arts and other sources: YouTube, discussion forums, readers’ comments, etc. • empirical material drawn from life: • Other’s anecdotes, circulating stories, written fragments, your/others’ memories; aphorisms, common metaphors, riddles, and sayings; • Empirical material drawn from imagination: • Sartre’s “The Look” (from Friesen 2014); Merleau Ponty and eye-contact The Anecdote: is to reflect, to think. • Anecdotes form part of the grammar of everyday storytelling. • Anecdotes recreate experiences, but …in a form that is: • focused, • condensed, • intensified, • oriented, and narrative • Sharing/writing/revising anecdotes is concrete reflecting prepares the space for phenomenological reflection. An anecdote… 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. is a very short and simple story. usually describes a single incident. begins close to the central moment of the experience. includes important concrete details. often contains several quotes (what was said, done, and so on). closes quickly after the climax or when the incident has passed. often has an effective or "punchy" last line: it creates punctum. [“often tells something noteworthy about life, about the promises and practices, frustrations and failures, events and accidents, disappointments and successes of our everyday living.”] Barthes, Camera Lucida Punctum • Photographs act on the body as much as on the mind • punctum …establishes a direct relationship with the object or person within it; • is a small, overlooked detail (accident) • the lacerating emphasis of the 'that-has-been‘ • I could have been in that pose, looked like that, done that; that reminds me of so-and-so, or of when I.... • An individual response of significant emotion: love, hate, but not “like” • NOT the obvious symbolic meaning (studium), but takes us beyond the photo itself Andre Kertész (1894 1985) Anecdotes and your “Phenomenon” 1. Determine sources for experiential narrative material …that are "examples" of the meaning …of the phenomenon that you [wish to] study 2. interpret what the significant theme(s) are that seem to emerge from the narrative as you read it against the backdrop of your research questionthe "lived experience phenomenon“ of your study . 3. Edit (rewrite) a promising narrative into a vivid anecdote by deleting extraneous or redundant material and retaining theme-relevant material. (Careful: do not overwrite, change, or distort the text.) Refining Anecdotes 4. Check or consult with the source (such as interviewee or author) of the narrative to determine iconic validity (but don't confuse iconic validity with empirical or factual validity). Ask: Does this anecdote show what an aspect of your experience is/was like? 5. Next, strengthen and refine (edit) the anecdote further into the direction of the phenomenon and its theme(s). 6. Ask yourself and other readers: "Does this anecdote show what an aspect of meaning of this experience is or was like?" 7. Don't forget that good writing is almost always honing the text through rewriting. • Remain constantly oriented to the lived experience of the phenomenon. • Edit the factual content but do not change the phenomenological content. • Enhance the eidetic or phenomenological theme by strengthening it. • Aim for the text to acquire strongly embedded meaning. • When a text is written in the present tense, it can make an anecdote more vocative. • Use of personal pronouns tends to pull the reader in. • Extraneous material should be omitted. • Search for words that are "just right" in exchange for awkward words. • Avoid generalizing statements and theoretical terminology. • Do not rewrite or edit more than absolutely necessary. “Exemplarity in Singularity” • They can do this because the exemplary anecdote, like literary fiction, always orients to the singular. • Phenomenology reflects on examples in order to discover what is exemplary and singular about a phenomenon or event. Examples in phenomenological inquiry serve to examine and express the aspects of meaning of a phenomenoni examples in phenomenology • have evidential significance: the example is the example of something experientially • knowable or understandable that is not directly sayable-a singularity. Poetic Intensification (Compression); Mantic • I may … feel that I have been captured by a certain feeling or emotion that is somehow evoked, not by the semantic meaning of the words I am hearing, but by their mantic or expressive effects. This mantic (“prophetic”) meaning of words may present itself when listening to a song whose lyrics are heard not for their content but for their mantic effect. In such case, the words of the singer have become a sound that fuses with the other instruments of the musical piece. Heidegger: Dwelling Poetically • he shows how for Hölderlin, poetry provides us with a measure of what it means to dwell on the earth. Of course, the term measure for the poet does not refer to some number or measure in a calculative sense. In Heidegger's words, "the nature of measure is no more a quantum than is the nature of number. True we can reckon with numbers-but not with the nature of number" (Heidegger, 2001, p. 224). • “The essence of technology is by no means technological” • “The sciences do not think” • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1gK1S8mJ5bM Pathic Knowledge • pathic refers to the general mood, sensibility; felt sense of being in the world • Heidegger: Befindlichkeit ("the way one finds oneself“) to refer to the sense that we have of ourselves in situations; the implicit felt understanding of ourselves in situations • E. Gendlin: "It is sensed or felt, rather than thought--and it may not even be sensed or felt directly with attention.” The limits of positive, explicit knowledge 476. Children do not learn that books exist, that armchairs exist[. T]hey learn to fetch books, sit in armchairs, etc… 478. Does a child believe that milk exists? Or does it know that milk exists? Does a cat know that a mouse exists? 479. Are we to say that the knowledge that there are physical objects comes very early or very late?... 480. …Admittedly it’s true that ‘knowing something’ doesn’t [necessarily] involve thinking about it.” (On Certainty) Pathic knowledge/understanding • It is much easier for us to teach concepts and informational knowledge than …to bring about pathic understandings. • But phenomenology can be: “sensitive to the thoughtfulness required in contingent, ethical, and relational situations.” • But [it] …is through pathic significations and images, accessible through phenomenological texts that speak to us and make a demand on us, • In this way, “the more noncognitive dimensions of our professional practice may also be communicated, internalized, and reflected upon. “Even our gestures, the way we smile, the tone of our voice, the tilt of our head, and the way we look the other in the eye are expressive of the ways we know our world and comport ourselves in this world. On the one hand, our actions are sedimented into habituations, routines, kinesthetic memories. We do things in response to the rituals of the situation in which we find ourselves. On the other hand, our actions are sensitive to the contingencies, novelties, and expectancies of our world.” “In praise of tiredness” [It] is the tired person, rather than the person who [is] fresh and wide-awake who is the most sensitive to flows and atmospheres. Of course, there are many forms of tiredness, such as tense or nervous exhaustion which can make one weak, and can prevent sleep. But our concern here is with a more benevolent form of tiredness, one that slackens the whole body without leaving any knots or points of tension whatever. In this kind of tiredness, the body comes to its own, the breath flows steadily and independently. [...] This kind of tiredness not only increases emotional alertness, it also boosts one’s capability for empathic embodied communication. (Schmitz, as quoted in: Soentgen 1998, p. 75) Kockelmans: Introduction to Linschoten • Often an appeal to poetry and literature is almost unavoidable in that poetic language with its use of symbolism is able to refer beyond the realm of what can be said “clearly and distinctly.” In other words ... in human reality there are certain phenomena which reach so deeply into a man's life and the world in which he lives that poetic language is the only adequate way through which to point to and to make present a meaning which we are unable to express clearly in any other way. ( 1987, p. ix) Linschoten: • Falling asleep means that the world falls asleep and wraps itself in stilling silence; • Sleep is a meditation of the body that surrenders and relaxes its hold on the world; • boredom does not precede sleep but is the inability to sleep; • insomnia is the sign of an insecurity or uncertainty that makes it impossible to "leave" the world. Merleau-Ponty’s preface • Phenomenology allows itself to be practiced and recognized as a manner or as a style, or that it exists as a movement, prior to having reached a full philosophical consciousness. • Phenomenology involves describing, and not explaining or analyzing. • To return to the things themselves is to return to this world prior to knowledge, this world of which knowledge always speaks… • Perhaps the best formulation of the reduction is the one offered by Husserl's assistant Eugen Fink when he spoke of a "wonder" before the world. Reflection does not withdraw from the world toward the unity of consciousness as the foundation of the world; rather, it steps back in order to see transcendences spring forth and it loosens the intentional threads that connect us to the world in order to make them appear; it alone is conscious of the world because it reveals the world as strange and paradoxical. Phenomenology's most important accomplishment is… to have joined an extreme subjectivism with an extreme objectivism through its concept of the world or of rationality. Rationality fits precisely to the experiences in which it is revealed. There is rationality – that is, perspectives intersect, perceptions confirm each other, and a sense appears. But this sense must not be separated, transformed into an absolute Spirit, or transformed into a world in the realist sense. The phenomenological world is not pure being, but rather the sense that shines forth at the intersection of my experiences and at the intersection of my experiences with those of others through a sort of gearing into each other.