Therapy of human rabies

advertisement

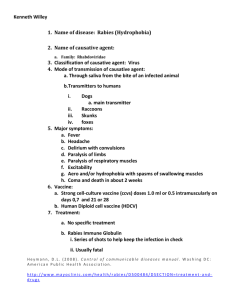

Therapy of human rabies: lessons from experimental studies in a mouse model Alan C. Jackson, MD Courtney A. Scott, BSc James Owen, BSc Simon C. Weli, PhD John P. Rossiter, MB, PhD Departments of Medicine (Neurology) Microbiology and Immunology Centre for Neuroscience Studies Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada Medical complications of rabies multisystem organ failure respiratory failure, hyperventilation, aspiration pneumonia cardiac failure, arrhythmias gastrointestinal hemorrhage hyperthermia or hypothermia endocrine – SIADH, DI Recovery from rabies 6-yr-old male from Ohio. Hattwick et al. Ann Intern Med (1972) 45-yr-old female from Argentina. Porras et al. Ann Intern Med (1976) 32-yr-old male lab worker from New York. Tillotson et al. MMWR (1977) 9-yr-old male from Mexico. Alvarez et al. Pediatr Infect Dis (1994) 6-yr-old female from India. Madhusudana et al. Int J Infect Dis (2002) Clinical Infectious Diseases 36:60-63, 2003 Specific therapies rabies vaccine human rabies immune globulin (or mabs) ribavirin interferon- ketamine role of combination therapy? Jackson et al.: Clinical Infectious Diseases 36:60-63, 2003 N Engl J Med 352:2508-14, 2005 Survival Case healthy 15-year-old in Wisconsin bitten by bat – probable bat rabies virus (no virus isolated, no antigen or RNA identified) antibodies on presentation (RFFIT 1:102) midazolam infusion to produce burst suppression pattern on EEG with supplemental phenobarbital IV ketamine infusion 2 mg/kg/hr antiviral therapy with ribavirin (IV) and amantadine N Engl J Med 352:2508-14, 2005 Survival Case Did specific therapy play important role in recovery? therapeutic coma?? ketamine? antiviral therapy? Attenuated bat rabies virus strain? Early antibody response Lack of detection of viral antigen and RNA, suggests that effective viral clearance was in progress Ketamine dissociative anesthetic agent ketamine (1-2 mM) inhibits in vitro replication of rabies virus by inhibiting genome transcription with stereotaxic inoculation of fixed rabies virus into neostriatum of rats, ketamine 60 mg/kg IP q12h reduced infection in multiple brain regions (hippocampus, cerebral cortex, and thalamus) Lockhart et al. – Antiviral Chem Chemother 1991 and 1992 Antimicro Agents Chemother 1991 Journal of Virology 80:10270, 2006 Toluidine blue-stained plastic sections cerebral cortex – 48 hrs Mock-infected CVS-infected J Virol 80:10270, 2006 Trypan blue exclusion cerebral cortex – 72 hrs Mock-infected CVS-infected J Virol 80:10270, 2006 Trypan Blue Staining Cerebral Cortex Hippocampus Cerebral Cortex 100 100 80 80 % of viable cells % of viable cells Hippocam pus 60 40 60 40 20 20 0 0 1 2 1 3 2 3 Days Days Mock-infected CVS J Virol 80:10270, 2006 Effects of 125 μM ketamine on viability of cortical neurons in CVS infection J Virol 80:10270, 2006 Cumulative mortality ketamine 60 mg IP q12h or vehicle intracerebral log rank test p= 0.50 footpad log rank test p= 0.53 J Virol 80:10270, 2006 Therapy with Ketamine Ketamine did not: • • • • • reduce mortality attenuate the clinical neurologic illness or prolong survival reduce viral spread or the number of infected neurons reduce the amount of infectious virus reduce neuronal apoptosis after intracerebral inoculation Lancet Neurology 3:744, 2004 multiple sclerosis spinal cord injury Parkinson’s disease Huntington’s disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis viral diseases of CNS – reovirus, SIV, Sindbis v. Journal of Virology 81:6248, 2007 log rank test p=0.003 J Virol 81:6248, 2007 Summary Therapy with minocycline (50 mg/kg/d) was associated with more severe neurologic disease and higher mortality than with vehicle in rabies virus – infected mice. The number of rabies virus-infected neurons was similar with vehicle and minocycline. Neuronal apoptosis was more marked in infected mice that received vehicle than minocycline (minocycline was anti-apoptotic). There were smaller numbers of CD3 positive cells in the brainstem of mice that received minocycline than vehicle, indicating an anti-inflammatory effect of the drug. J Virol 81:6248, 2007 Conclusions Therapy of rabies with minocycline in an experimental mouse model did not provide neuroprotection and aggravated the neurological disease. Caution should be taken before using minocycline for empirical therapy of rabies or other viral encephalitis in humans before more experimental data become available. Therapeutic approach similar to the Willoughby protocol has been unsuccessful in at least 8 cases: • United States – 3 (TX, IN, CA) • Canada (Alberta) • Germany – 2 • India • Thailand Conclusions: Ketamine Lack of efficacy of ketamine in about 8 human cases since the Milwaukee case Lack of efficacy of ketamine in primary neuronal cultures and in vivo in mice at 120mg/kg/d More experimental evidence is needed that supports the use of ketamine in rabies virus infection before recommending its use for the therapy of human rabies. Therapeutic coma useful for therapy of status epilepticus efficacy in other neurologic disorders is unproven no experimental evidence of efficacy in rabies or any other infectious disease potential serious adverse effects lack of effective neuroprotective agents even in common acute neurologic disorders (e.g., stroke), despite numerous clinical trials no scientific rationale for use in rabies does not work risks outweigh benefits should not be used for human rabies Willoughby protocol • • • • • Multiple failures of the protocol in developed and developing countries. It is now highly questionable that therapy using this protocol was directly responsible for the favorable outcome. This protocol should not be repeated indefinitely. Experimental work should be performed in cell culture and in animal models to identify promising therapeutic agents. New approaches should be taken for future rabies patients. Acknowledgments Queen’s University Violet E. Powell Fund