Introduction to the PICU and Airway Management

advertisement

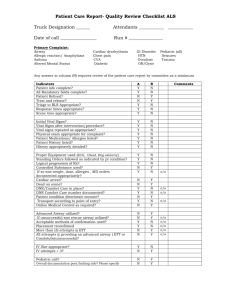

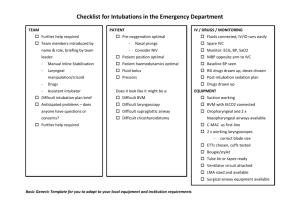

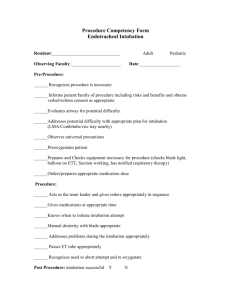

UTHSCSA Pediatric Resident Curriculum for the PICU Introduction to the PICU and Airway Management The Purpose of Intensive Care Units exist to monitor patients for acute deterioration Units are staffed by personnel trained to react to deterioration with advanced skills Success in management favors the prepared mind Keys to Success Perform the same approach on every patient each day Collect information (exam, notes, labs) construct a coherent picture, develop an assessment and formulate a plan Present in a consistent manner Predict what problems may develop Airway Management The ability to recognize impending respiratory failure and stabilize an airway is one of the cornerstones of ICU management Knowledge of the pediatric airway and proficiency in its stabilization and intubation is essential Laryngeal Cartilages Laryngeal Anatomy (Infant) Laryngeal Anatomy Sensory innervation occurs from the internal branch of the superior and recurrent laryngeal nerve, motor innervation is from the recurrent laryngeal nerve Blood supply is provided by the superior and inferior thyroid arteries Four Differences between the Adult and Pediatric Airway • Infant tongue is proportionally large • The infants larynx is higher (rostral) in the neck (C3-4) than an adults (C4-5) • The infants epiglottis is omega shaped () and angled away from the trachea • The narrowest part of the larynx is the cricoid cartilage below the vocal cords Larynx Configuration Adult (cylinder) Pediatric (funnel) Airway Diameter and Resistance Obstructed Inspiration/Expiration Stridor Wheezing Work of Breathing Product of Compliance and Resistance Nasal passages account for 25% of airflow resistance in infants, 60% in adults Most resistance in infants occurs in the small airways – small diameter – lack of supporting structures Work of Breathing WOB per kilogram body weigh is similar in adults and children. Higher respiratory rates are due to greater O2 consumption – (4-6 ml/kg/min) infants, (2-3 ml/kg/min) adults Infant have diaphragm and intercostal muscles with fewer Type 1 (slow-twitch) fibers so they are more prone to fatigue Airway Management The Goal of Airway management is to anticipate and recognize respiratory problems and to support or replace those that are compromised or lost Pediatric Advance Life Support Manual Important to Remember An individual must be able to support three specific functions: – Protect their airway – Adequately ventilate – Adequately oxygenate A failure to perform any ONE function will result in respiratory failure. Airway Control There are many simple, non-invasive techniques to support respiration prior to undertaking endotracheal intubation – Application of oxygen – Suctioning – Positioning of the airway – Application of positive pressure – Assistance of ventilation with a BVM Application of Oxygen Nasal canula (23-25%) Simple face mask (35-60%) Non-rebreather mask (80-100%) – High flow (10-12 l/min) – Reservoir of oxygen – Tight-fitting to face – Valves to prevent entrainment of room air Suctioning The inability of infants to generate a strong cough together with their small airways makes removal of tracheal secretions important to assure patency Infants are obligate nasal breathers and become unruly when their nose is obstructed. Many an infant was saved from intubation by a bulb suction! POSITIONING Use of the chin lift and jaw thrust can help restore flow through an obstructed upper airway by separating the tongue from posterior pharyngeal structures. The goal is to line up three divergent axes: oral, pharyngeal and tracheal. Aligning the Axes (Initial) Aligning the Axis (Occiput Roll) Aligning the Axis (Extension) Oropharyngeal Airways Facilitates relief of upper airway obstruction due to a large tongue Allows oropharyngeal suctioning Prevents compression of a child’s endotracheal tube due to biting. Oropharyngeal Tube Selection Bag-Valve-Mask Masks should fit easily over the nose and mouth with no pressure on the eyes The base of the mask rests on the chin Valves allow unidirectional flow of oxygen to the patient and prevent entrainment of exhaled waste gas into the system Bag-Valve-Mask There are two types of bags, anesthesia and self-inflating Anesthesia bags require a perfectly closed system to operate and allow finer control of inspiratory and expiratory pressures. Without oxygen flow, the bag will not inflate. Anesthesia Bag Self-Inflating Bag Allows rapid ventilation of a patient in an emergency because it does not need an oxygen source to operate Requires the use of a reservoir to deliver 100% oxygen, otherwise it entrains some room air with the oxygen Requires a PEEP valve to deliver specific end-expiratory pressures. Self-Inflating Bag Preparation for Endotracheal Intubation Use history and physical exam to predict a difficult airway Exam clues to the difficult airway – Mouth opening test – Loose teeth – Mandible space (genu to thyroid cartilage) – Presence of congenital abnormalities Preparation for Endotracheal Intubation Gather all necessities – Needed personnel – Appropriate endotracheal tubes – Appropriate laryngoscope blades – Airway adjuncts ( stylets, oral airways etc.) – Suctioning equipment – BVM attached to oxygen at proper flow – Medications Miller Vs Macintosh Miller (straight) blades are used to lift the epiglottis & expose the vocal cords – usually used in infants and small children Macintosh (curved) blades are placed into the vallecula lifting the base of the tongue which in turn lifts the epiglottis. – Used primarily in older children and adults Miller and Macintosh Placement Procedure for intubation Successful intubation involves a series of 6 separate maneuvers. – proper sedation (when required) – proper positioning (align the axis) – establishing a patent airway (BVM) – sweeping the tongue – visualization of the airway/cords – placement of the endotracheal tube Anatomic Landmarks Intubation faux pas “Shoulder rolls” in children 2 or older Laryngoscopes held in the right hand Using the teeth as a fulcrum (tooth fairy) Passing the endotracheal tube down the barrel of the laryngoscope Neck extension when spinal cord injury is suspected Early release of cricoid pressure Post-intubation considerations Bilateral breath sounds before tube secured and chest x-ray ordered NGT in place for gastric decompression Tube migration into right mainstem or esophagus Suctioning the tube following placement Ventilator settings provided Special Situations Trauma patient in a C-collar Downs, Pierre-Robin and why can’t I see the vocal cords Pulmonary Edema Laryngospasm Full Stomach