Lora Nesifort Hamlet's Madness Within the story of “Hamlet” by

advertisement

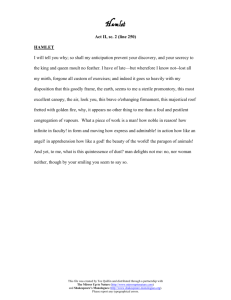

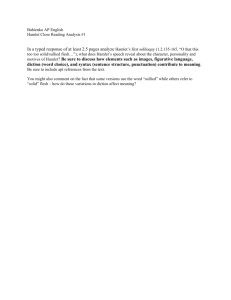

Lora Nesifort Hamlet’s Madness Within the story of “Hamlet” by Shakespeare, we see the main character go through a variety of emotions and temperaments. Because of these rollercoaster’s of emotions, many have come to the conclusion that Hamlet has in fact gone mad. Although many have agreed to his madness, the argument lines within the cause of it. Many theories have been claimed and even more have been attempted to be proven. One of the theories that have I have concurred with is the notion that Hamlet’s madness was provoked by his family and surrounding, as well as his grief. (a paragraph explaining a theory that explains a cause I disagree with will be here) The grief of losing a loved one is in fact one of the hardest things in life to go through and experience firsthand. In order to get through this period one must go through the five stages of grief. Within Hamlet’s grieving period we see that he goes through two of the five stages of grief which are anger and depression. Throughout the book we see many instances where Hamlet is angry and full of uncontrollable emotions that show the severity of his madness. An example of his anger would be in Act II, scene 2 when Hamlet, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are having a conversation and Hamlet compares Denmark to a prison and calling it the worst prison there is (ActII, Scene2 234-236). His demeanor and whole attitude portrays his anger towards Denmark and generally towards his life. He also shows a great deal of depression and also displays this stage of grief. In Act I, scene 2, we begin to see his depression in the words of one of his famous soliloquys. He says “Oh, that this too, too sullied flesh would melt, thaw, and resolve itself into a dew, or that the everlasting had not fixed his canon ‘gainst his self slaughter! (Act I, Scene2 129132). Being that thoughts of suicide is in fact a sign of depression, this is a good example that shows how he was depressed so much so that he was suicidal. Another example of his suicidal thoughts would be in one of his other speeches, “To be, or not to be? This is the questionwhether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take arms against a sea of troubles, and by opposing, end them? (Act III, Scene1 57-64). Once again he shows that the idea of taking his own life isn’t far from his thoughts and you can see that he is in conflict with himself on whether or not he should act with this perception. Arthur Kirsch, the author of an article called “Hamlet’s Grief” shows how Hamlet’s madness is associated with his grief. He points out a very noticeable event that occurs in Act I Scene 2, lines 68-86 when Gertrude and Hamlet first appear in a scene together and Gertrude asks Hamlet why he’s still wearing black clothing mourning his father’s death. Kirsch begins to show how Hamlet’s response “is speaking of the early stages of grief, of its shock, of its inner and still hidden sense of loss, and trying to describe what is not fully describable-the literally inexpressible wound whose immediate consequence is the dislocation, if not transvaluation, of our customary perceptions and feelings and attachments to life.”(Kirsch19). Kirsch also points out how the people who surrounded him helped inflict more grief on him by ignoring him and not being sympathetic to his grief. He said “What a person who is grieving needs, of course, is not the consolation of words, even words which are true, but sympathy- and this Hamlet does not receive, not from the court, not from his uncle, and more important, not from his own mother, to whom his grief over his father's death is alien and unwelcome.”(Kirsch 20). We see how unsympathetic King Claudius acts towards Hamlet in Act I Scene 2 lines 87-117 when he basically tells Hamlet that he is taking the death of his father way out of proportion and that it is emasculate and selfish for him to continue to act in this manner, telling him that he is being irrational since everyone that lives must die. Citation 1. Kirsch, Arthur. “Hamlet’s Grief.” ELH 48.1 (1981): 17-36. JSTOR. Web. 4 March. 2011.