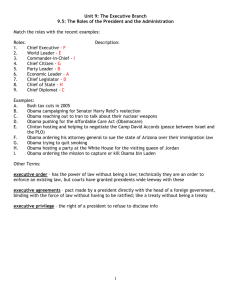

Michigan-Pappas-Allen-Neg-Kentucky-Round1

advertisement