Application Profiles Decisions for Your Digital Collections

advertisement

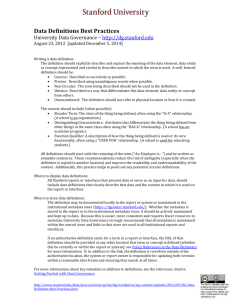

Application Profiles Decisions for Your Digital Collections Expectations “Metadata is expected to follow existing and emerging standards in order to facilitate integrated access to multiple information providers over the web. However, there are many new standards, and most of them are still under development . . . Standards landscape The plot thickens . . . . And it is rare that the requirements of a particular project or site can all be met by any one standard “straight from the box.” . . . and there are no easy answers The not-so-easy answer • Metadata application profiles • Tailor complex schemas for projectspecific usage • Collaborate with all project stakeholders tgm lcsh local w3cdtf lcnaf authorities, vocabularies metadata application profiles schemas tei mods mets mix ead marc dc local premis content standards dacs aacr2 local cco Application profiles: Basic Definition schemas which consist of data elements drawn from one or more namespaces, combined together by implementers, and optimized for a particular local application. -- Heery, R. and Patel, M. Application profiles: mixing and matching metadata schemas. Ariadne 25, Sept. 24, 2000 http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue25/appprofiles/intro.html Schema A Records Schema B Schema C Application Profile Records Example Australia Government Locator Service Manual http://www.egov.vic.gov.au/pdfs/AGLSmanual.pdf Title Date Language Type Source Availability Audience Identifier Publisher Subject Format Relation Function Mandate Creator Contributor Description Coverage Rights Basic Definition (cont.) An application profile is an assemblage of metadata elements selected from one or more metadata schemas and combined in a compound schema. -- Duval, E., et al. Metadata Principles and Practicalities D-Lib Magazine, April 2002 http://www.dlib.org/dlib/april02/weibel/04weibel.html Profile features • Selection of applicable elements, subelements and attributes • Interpretation of element usage • Element constraints – Mandatory, optional or recommended – Repeatable or non-repeatable • If repeatable, maximum no. of occurrences – Fixed or open values – Authority controlled or not Designing of Application Profiles • Select “base” metadata namespace • Select elements from other metadata name spaces • Define local metadata elements • Enforcement of applications of the elements – – – Cardinality enforcement Value Space Restriction Relationship and dependency specification • Select “base” metadata namespace • Select elements from other metadata name spaces • Define local metadata elements • Enforcement of applications of the elements – – – Cardinality enforcement Value Space Restriction Relationship and dependency specification • -- Dublin Core • --13 elements (no source, no relation) • --thesis.degree • -- some changed from “optional to “mandatory” • -- recommended default value, in addition to DC’s • -- new refinement terms DC-Lib A library application profile will be a specification that defines the following: • • • • required elements permitted Dublin Core elements permitted Dublin Core qualifiers permitted schemes and values (e.g. use of a specific controlled vocabulary or encoding scheme) • library domain elements used from another namespace • additional elements/qualifiers from other application profiles that may be used (e.g. DC-Education: Audience) • refinement of standard definitions … use terms from multiple namespaces The DC-Library Application Profile uses terms from two namespaces: • DCMI Metadata Terms [http://dublincore.org/documents/dcmi-terms/] • MODS elements used in DC-Lib application profile [http://www.loc.gov/mods] • The Usage Board has decided that any encoding scheme that has a URI defined in a non-DCMI namespace may be used. Can an AP declare new metadata terms (elements and refinements) and definitions? "If an implementor wishes to create 'new' elements that do not exist elsewhere then (under this model) they must create their own namespace schema, and take responsibility for 'declaring' and maintaining that schema." Heery and Patel (2000) Dublin Core Application Profile Guidelines [CEN, 2003] also includes instructions on "Identifying terms with appropriate precision" (Section 3) and "Declaring new elements" (Section 5.7) Creating Metadata Records • The “Library Model” – Trained catalogers, one-at-a-time metadata records • The “Submission Model” – Creators (agents) create metadata when submitting resources • The “Automated Model” – Automated tools create metadata for resources • “Combination Approaches” The Library Model • Records created “by hand,” one at a time • Shared documentation and content standards (AACR2, etc.) • Efficiencies achieved by sharing information on commonly held resources • Not easily extended past the granularity assumptions in current practice The Submission Model • Based on creator or user generated metadata • Can be wildly inconsistent – Submitters generally untrained – May be expert in one area, clueless in others • Often requires editing support for usability • Inexpensive, may not be satisfactory as an only option The Automated Model • Based largely on text analysis; doesn’t usually extend well to non-text or low-text • Requires development of appropriate evaluation and editing processes • Still largely research; few large, successful production examples, yet • Can be done in batch • Also works for technical as well as descriptive metadata Content “Storage” Models • “Storage” related to the relationships between metadata and content • These relationships affect how access to the information is accomplished, and how the metadata either helps or hinders the process (or is irrelevant to it) Common “Storage” Models • Content with metadata • Metadata only • Service only Content with metadata • Examples: – HTML pages with embedded ‘meta’ tags – Most content management systems (though they may store only technical or structural metadata – Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) • Often difficult to update Metadata only • Library catalogs – Web-based catalogs often provide some services for digital content • Electronic Resource Management Systems (ERMS) – Provide metadata records for title level only • Metadata aggregations – Using OAI-PMH for harvest and re-distribution Service only • Often supported partially or fully by metadata – Google, Yahoo (and others) • Sometimes provide both search services and distributed search software – Electronic journals (article level) • Linked using “link resolvers” or available independently from websites • Have metadata behind their services but don’t generally distribute it separately Common Retrieval Models • Library catalogs – Based on a consensus that granular metadata is useful • Web-based (“Amazoogle”) – Based primarily on full-text searching and linkor usage-based relevance ranking • Portals and federations – Service provider model Nine Questions to Guide You in Choosing a Metadata Schema • Who will be using the collection? • Who is the collection cataloger (a.k.a. metadata creator)? • How much time/money do you have? • How will your collection be accessed? • How is your collection related to other collections? Nine Questions to Guide You in Choosing a Metadata Schema • What is the scope of your collection? • Will your metadata be harvested? • Do you want your collection to work with other collections? • How much maintenance and quality control do you wish? Decisions for Your Digital Collection • 1. Considering metadata in a larger project setting • Organization-wide collaborative – – – – Library Special collections Archives Academic departments, business departments • State-wide collaborative projects – E.g., Ohio Memory • Nation-wide projects – E.g., American Memory Decisions for Your Digital Collection • Similar or related disciplines – E.g., architecture projects, art projects • Similar or related media – E.g., multimedia database, image galleries, visual resources repositories, manuscript collections, company procedure documents … Principles to be considered • Interoperability – Your data can be integrated into a larger project. – Your data structure allows others to join you. • Metadata reuse – Existing MARC or EAD records can be reused. Principles to be considered • Simplicity • High quality original data – Ensure best quality. – One-time project vs. ongoing projects – considering long life. Few revision chances in the future. 2. Knowing the difference • “Object"/"work" vs. reproduction • Textual vs. non-textual resources • Document-like vs. non-document-like objects • Collection-level vs. item-level How to describe …? • • • • • Describe what? The image itself? Or The building? The building as a building? Or A building which has a historical importance? Work vs. Image • A work is a physical entity that exists, has existed at some time in the past, or that could exist in the future. • An image is a visual representation of a work. It can exist in photomechanical, photographic and digital formats. Work vs. Image • A digital collection needs to decide what is the entity of their collection: – – – – works, images, or both? How many metadata records are needed for each entity? • Some part of the data can be reused. – E.g., one work has different images or different formats Document-like vs. nondocument-like Each object usually has the following characteristics: being in three dimensions, having multiple components carrying information about history, culture, and society, and demonstrating in detail about style, pattern, material, color, technique, etc. Textual vs. Non-textual • Text: – Would allow for full text searching or automatic extraction of keywords. – Marked by HTML or XML tags. – Tags have semantic meanings. • Non-textual, e.g., images: – Only the captions, file names can be searched, not the image itself. – Need transcribing or interpreting. – Need more detailed metadata to describe its contents. – Need knowledge to give a deeper interpretation. Determining What Metadata is Needed Who are your users? (current as well as potential) (e.g., library or registrarial staff, curators, professors, advanced researchers, students, general public, nonnative English speakers) What information do you already have (even if it’s only on index cards or in paper files)? What information is already in automated form? What metadata categories are you currently using? Are they adequate for all potential uses and users? Do they map to any standard? What is an adequate “core” record? Is your data clean and consistent enough to migrate? (You may consider re-keying in some cases.) Data Standards: Essential Steps • First Step: Select and Use Appropriate Metadata Elements – Data Structure Standards (a.k.a. metadata standards) – Elements describing the structure of metadata records: What elements should a record include? – Meant to be customized according to institutional needs – MARC, EAD, MODS, Dublin Core, CDWA, VRA Core are examples of data structure standards A Typology of Data Standards Data structure standards (metadata element sets): MARC, EAD, Dublin Core, CDWA, VRA Core, TEI Data value standards (vocabularies): LCSH, LCNAF, TGM, AAT, ULAN, TGN, ICONCLASS Data content standards (cataloging rules): AACR (RDA), ISBD, CCO, DACS Data format/technical interchange standards (metadata standards expressed in machine-readable form): MARC, MARCXML, MODS, EAD, CDWA Lite XML, Dublin Core Simple XML schema, VRA Core 4.0 XML schema, TEI XML DTD Data Standards: Essential Steps • Second Step: Select and Use Vocabularies, Thesauri, & local authority files – Data Value Standards – Data values are used to “populate” or fill metadata elements – Examples are LSCH, AAT, TGM, MeSH, ICONCLASS, etc., as well as collection-specific thesauri & controlled lists – Used as controlled vocabularies or authorities to assist with documentation and cataloging – Used as research tools – vocabularies contain rich information and contextual knowledge – Used as search assistants in database retrieval systems or with online collections Data Standards: Essential Steps • Third Step: Follow Guidelines for Documentation – Data Content Standards – Best practices for documentation (i.e. implementing data structure and data value standards) – Rules for the selection, organization, and formatting of content – AACR (Anglo American Cataloguing Rules), CCO (Cataloging Cultural Objects), DACS (Describing Archives: A Content Standard), local cataloging rules Data Standards: Essential Steps • Fourth Step: • Select the Appropriate Format for Expressing/Publishing Data – DATA FORMAT STANDARDS – How will you “publish” and share your data in electronic form? – How will service providers obtain, add value to, and disseminate your data? – Some candidates are Dublin Core XML; MARC21; MARC XML; CDWA Lite XML schema; MODS, etc. Metadata for the Web • The Web is not a “library”! • Web searching is abysmal • Some (primitive) Web metadata exists, but few implement with consistency: • TITLE html tag • DESCRIPTION meta tag • KEYWORDS meta tag • “No index, no follow” meta tag “Indexing for the Internet” • End-users tend to employ broader, more generic terms than catalogers (“folk classification”) • Indexers must try to anticipate what terms users, who typically have “information gaps,” would use to find the item in hand • Users shouldn’t be required to input the “right” term Speaking of the Web... • Are your collections “reachable” by commercial search engines? (Visible Web vs. Deep Web) • If yes, how will you “contextualize” individual collection objects? • If not, what is your strategy to lead Web users to your search page? • Contributing to union catalogs (via metadata harvesting, etc.) will provide greater exposure for your collections The Google Factor • What Google looks at – title tag – text on the Web page – referring links • What Google doesn’t look at (usually) – Keywords meta tag – Description meta tag searchenginewatch.com provides information on how commercial search engines work Good Metadata … …facilitates data mapping, rationalization & harmonization, and thus makes interoperability (federated searching, cross-collection searching) possible, and possibly understandable Practical Principles for Metadata Creation and Maintenance • Metadata creation is one of the core activities of collecting and memory institutions. • Metadata creation is an incremental process and should be a shared responsibility • Metadata rules and processes must be enforced in all appropriate units of an institution. Practical Principles for Metadata Creation and Maintenance • Adequate, carefully thought-out staffing levels including appropriate skill sets are essential for the successful implementation of a cohesive, comprehensive metadata strategy. • Institutions must build heritability of metadata into core information systems. Practical Principles for Metadata Creation and Maintenance • There is no "one-size-fits-all" metadata schema or controlled vocabulary or data content (cataloging) standard • Institutions must streamline metadata production and replace manual methods of metadata creation with "industrial" production methods wherever possible and appropriate. Practical Principles for Metadata Creation and Maintenance • Institutions should make the creation of shareable, re-purposable metadata a routine part of their work flow. • Research and documentation of rights metadata must be an integral part of an institution's metadata workflow. • A high-level understanding of the importance of metadata and buy-in from upper management are essential for the successful implementation of a metadata strategy. Metadata Principles • Metadata Principle 1: Good metadata conforms to community standards in a way that is appropriate to the materials in the collection, users of the collection, and current and potential future uses of the collection. • Metadata Principle 2: Good metadata supports interoperability. • Metadata Principle 3: Good metadata uses authority control and content standards to describe objects and collocate related objects. Metadata Principles • Metadata Principle 4: Good metadata includes a clear statement of the conditions and terms of use for the digital object • Metadata Principle 5: Good metadata supports the long-term management, curation, and preservation of objects in collections. • Metadata Principle 6: Good metadata records are objects themselves and therefore should have the qualities of good objects, including authority, authenticity, archivability, persistence, and unique identification. Metadata • “Metadata”—which in many ways can be seen as a late 20th-early 21st-century synonym for “cataloging”—is seen as an increasingly important (albeit frequently sloppy, and often confounding) aspect of the explosion of information available in electronic form, and of individuals’ and institutions’ attempts to provide online access to their collections. Metadata for enhanced access • Librarians, archivists, and museum documentation specialists can and should make metadata creation into a viable, effective tool for enhancing access to the myriad resources that are now available in electronic form. The judicious, carefully considered combination of various standards can facilitate this. Mixing and matching A recent trend in metadata creation is “schemaagnostic” metadata. Description as a collaborative process • Description (a.k.a. cataloging) should be seen as a collaborative, incremental process, rather than an activity that takes place exclusively in a single department within an institution (in libraries, this has traditionally been the technical services department). • Metadata creation in the age of digital resources can and indeed should in many cases be a collaborative effort in which a variety of metadata—technical, descriptive, administrative, rights-related, and so on) is added incrementally by trained staff in a variety of departments, including but not limited to the registrar’s office, digital imaging and digital asset management units, processing and cataloging units, and conservation and curatorial departments.* • What about “expert social tagging”? What will it take? • Technical infrastructure and tools • “Behavioral/cultural” and organizational changes • Hard work, and a more production oriented approach (more efficient workflows, decision trees, use of quotas, etc.) Some Emerging Trends in Metadata Creation “Schema-agnostic” metadata Metadata that is both shareable and re-purposable Harvestable metadata (OAI/PMH) “Non-exclusive”/”cross-cultural” metadata—i.e., it’s okay to combine standards from different metadata communities—e.g. MARC and CCO, DACS and AACR, DACS and CCO, EAD and CDWA Lite, etc. Importance of controlled vocabularies & authorities—and difficulties in “bringing along” the power of vocabularies in a shared metadata environment The need for practical, economically feasible approaches to metadata creation Metadata Librarians a.k.a. Catalogers? • Collaboration, not isolation • Metadata librarians don’t catalog • Emphasis on the collection, not the “item in hand” • Sometimes “good enough” is good enough – Collection size – Uniqueness – Online access • No more monoliths • LCSH: off with its head? Metadata Good Practices • Adherence to standards • Planning for persistence and maintenance • Documentation – Guidelines expressing community consensus – Specific practices and interpretation – Vocabulary usage – Application profiles • Without good metadata and good practices, interoperability will not work