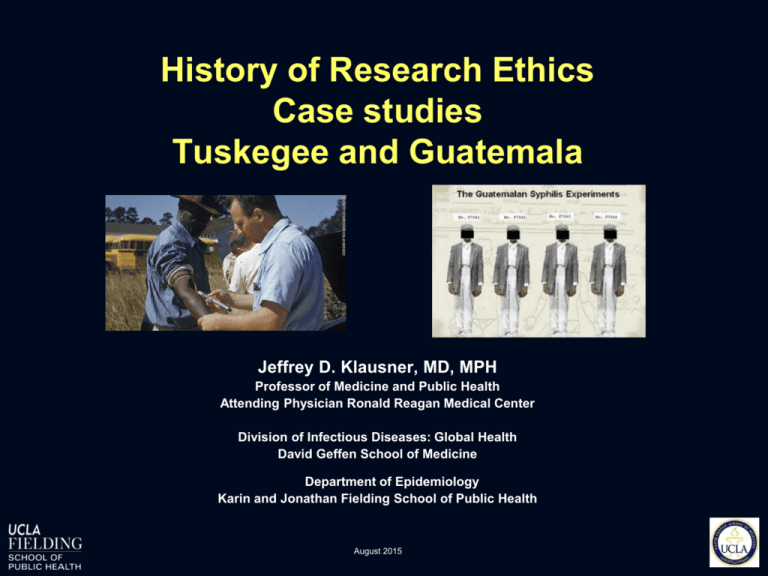

History of Research Ethics: Case Studies

advertisement

History of Research Ethics Case studies Tuskegee and Guatemala Jeffrey D. Klausner, MD, MPH Professor of Medicine and Public Health Attending Physician Ronald Reagan Medical Center Division of Infectious Diseases: Global Health David Geffen School of Medicine Department of Epidemiology Karin and Jonathan Fielding School of Public Health August 2015 Disclosures Dr. Klausner is a faculty member of the University of California Los Angeles Dr. Klausner is a guest researcher with the US CDC Mycotics Diseases Branch Dr. Klausner is a member of the WHO STI advisory group Dr. Klausner is a board member of YTH.org In the past 12 months, Dr. Klausner has received: Research grant funding, supplies or unrestricted gifts from the NIH, CDC, Hologic Inc., Orasure Inc., Cepheid, Healthvana Inc. JDKlausner@mednet.ucla.edu Outline • • • • Quick review of ethical principles Tuskegee syphilis experiment Guatemala syphilis experiment Small group discussion and report back Research Ethical Principles • Respect for Persons • Beneficience • Justice http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/belmont.html [1979] Application of Research Ethical Principles Principle Practice Respect for Persons Informed consent Beneficience Risks and benefits Justice Selection of subjects Tuskegee Study 1932-1972 • Macon County, Alabama, pop. 11,846 • To study the natural progression of untreated syphilis in rural AfricanAmerican men • US Public Health Services began the study in 1932 • Investigators enrolled in the study a total of 600 men: • 399 who had previously contracted syphilis • 201 without syphilis Tuskegee Study 1932-1972 • Research team included Tuskegee Institute, US Public Health Service doctors, Dr. Eugene Dibble and Nurse Eunice Rivers • Men were given free medical care, meals and free burial insurance • Study members were told they were being treated for "bad blood", a local term for various illnesses that included syphilis, anemia and fatigue Tuskegee Study 1932-1972 • In 1947, penicillin proven to be effective treatment for syphilis • Study participants never specifically told they had syphilis, nor were they ever treated for it • Researchers prevented men from being treated elsewhere • Post-World War II research requirements changed but not the Tuskegee Study Tuskegee Study 1932-1972 • In 1966, Peter Buxton, a venerealdisease investigator in San Francisco, raised concerns about the study • The CDC reconfirmed the study’s value along with: • National Medical Association • American Medical Association • In 1972, Washington Star broke the story, followed by NY Times • Investigation ensued and study terminated Tuskegee Study 1932-1972 • USG paid $9M to survivors and families • National Research Act 1974 • Belmont Report (1979) included guidelines for ethics in medical research President Clinton Apology May 16th, 1997 • • “…today America does remember the hundreds of men used in research without their knowledge and consent. Men who were poor and African American, without resources and with few alternatives, they believed they had found hope when they were offered free medical care by the United States Public Health Service. They were betrayed.” The United States government did something that was wrong—deeply, profoundly, morally wrong. It was an outrage to our commitment to integrity and equality for all our citizens... clearly racist. Real Time with Bill Maher March 6, 2007 Video American J Public Health, 1991 The Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis in the Negro male is the longest non-therapeutic experiment on human beings in medical history. The strategies used to recruit and retain participants were quite similar to those being advocated for HIV/AIDS prevention programs today. Almost 60 years after the study began, there remains a trail of distrust and suspicion that hampers HIV education efforts in Black communities. The AIDS epidemic has exposed the Tuskegee study as a historical marker for the legitimate discontent of Blacks with the public health system. The belief that AIDS is a form of genocide is rooted in a social context in which Black Americans, faced with persistent inequality, believe in conspiracy theories about Whites against Blacks. These theories range from the belief that the government promotes drug abuse in Black communities to the belief that HIV is a manmade weapon of racial warfare. An open and honest discussion of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study can facilitate the process of rebuilding trust between the Black community and public health authorities. This dialogue can contribute to the development of HIV education programs that are scientifically sound, culturally sensitive, and ethnically acceptable. Thomas SB, Quinn SC. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, 1932 to 1972: implications for HIV education and AIDS risk education programs in the black community. Am J Public Health. 1991 Nov;81(11):1498-505. Community Impact of Tuskegee Study • What is the community impact? • Distrust, conspiracy, fear • ? Lack of participation in research and preventive health care Brandon DT J Natl Med Assoc. Jul 2005; 97(7): 951–956. RV Katz et al. American Journal of Public Health June 2008; 98 (6): 1137–1142 Guatemala 1946-1948 • US Public Health Service conducted syphilis experiments in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948. • Doctors infected soldiers, prisoners, and mental patients with syphilis without the informed consent of the subjects, and then treated them with antibiotics. • In October 2010, the U.S. formally apologized to Guatemala for conducting these experiments Special thanks to Prof. Jonathan Zenilman, Johns Hopkins University What Was Known? What were the Questions? By the end of World War II, the efficacy of Penicillin for Syphilis and Gonorrhea was being determined There was tremendous interest in preventive treatment of contacts STDs had tremendous impact on military deployability Standard medical texts of the day (eg Stokes, 1944) did not address preventive treatment Slide courtesy of J. Zenilman Syphilis rates per 1000, US, 1940 Slide courtesy of J. Zenilman Slide courtesy of J. Zenilman The Guatemala Study Questions Can a preventive treatment regimen be evaluated in a model where humans are infected under controlled conditions? Comparison groups—Orvus-Mapharsen (arsenical); Penicillin (at various doses), Controls Studies done in syphilis, gonorrhea, chancroid Sources of infected material—ground up solutions of syphilis organisms from rabbits; or transfer of human material (TP, GC, HD) Grant approved by the Syphilis Study Section, USPHS, February 1946 Slide courtesy of J. Zenilman Initial Approach--Develop the Model “Natural” infection Commercial Sex Workers Recruited Experimentally infected with T. pallidum Intercourse with Prison inmates or soldiers Evaluated immediately post coital and serially FINDING- Infection rate low—not useful for prevention experiments Slide courtesy of J. Zenilman Direct Infection Model--Syphilis Subject Population-Asylum, Prisoners Infection experiments: Evaluate pedigree T pallidum strains Swab transfer Pledgets Direct Inoculation Differences in dose, organism pedigree, swab placement time, “adjuvants” Followed by clinical exam, multiple RPR tests, subset lumbar punctures Slide courtesy of J. Zenilman Slide courtesy of J. Zenilman 7 months earlier… NY Times April 27, 1947 Slide courtesy of J. Zenilman Guatemala Discovery Timeline 2003—Dr Susan Reverby discovers Cutler records at University of Pittsburgh May 2010—Reverby notifies the former director of the CDC—Dr David Sencer Summer 2010—US recovers Cutler documents and starts formal review October 2010—Formal apology to Guatemala November 2010—President Obama directs the Presidential Commission on Bioethical Issues to investigate August 2011—Public Hearing December 2011—Full report Slide courtesy of J. Zenilman Susan M. Reverby, a Wellesley College Professor Guatemala Apology October 2010 Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton and Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius apologized to the government of Guatemala and the survivors and descendants of those infected. They called the experiments “clearly unethical.” “Although these events occurred more than 64 years ago, we are outraged that such reprehensible research could have occurred under the guise of public health,” the secretaries said in a statement. “We deeply regret that it happened, and we apologize to all the individuals who were affected by such abhorrent research practices.” Slide courtesy of J. Zenilman www.bioethics.gov Discussion • Were those syphilis studies unethical? Why? • In what situation could such studies be ethical, if ever? • What ethical principles were violated? What procedures exist to uphold those principles? • Tuskegee—Respect for Persons • Guatemala—Beneficience • How did the US respond to the study findings? • How do those experiences and common history relate to HIV/AIDS? Discussion • Agree or disagree and why? “The Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis in the Negro male is the longest nontherapeutic experiment on human beings in medical history. The strategies used to recruit and retain participants were quite similar to those being advocated for HIV/AIDS prevention programs today. Almost 60 years after the study began, there remains a trail of distrust and suspicion that hampers HIV education efforts in Black communities. The AIDS epidemic has exposed the Tuskegee study as a historical marker for the legitimate discontent of Blacks with the public health system. The belief that AIDS is a form of genocide is rooted in a social context in which Black Americans, faced with persistent inequality, believe in conspiracy theories about Whites against Blacks. These theories range from the belief that the government promotes drug abuse in Black communities to the belief that HIV is a manmade weapon of racial warfare. An open and honest discussion of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study can facilitate the process of rebuilding trust between the Black community and public health authorities. This dialogue can contribute to the development of HIV education programs that are scientifically sound, culturally sensitive, and ethnically acceptable.” S B Thomas and S C Quinn. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, 1932 to 1972: implications for HIV education and AIDS risk education programs in the black community. American Journal of Public Health November 1991: Vol. 81, No. 11, pp. 1498-1505.