Science fact sheet

advertisement

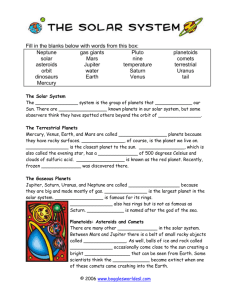

SCIENCE The Universe The Sun The Sun is an immense sphere of plasma; intensely hot, electrically charged gas, mostly hydrogen and helium. With a diameter of 1,391,000 kilometres, it dwarfs other members of our solar system. More than one million earths could fit into it. As it formed from the gas and grit of the solar nebulae, the sun sucked in virtually all matter for billions of miles, ending up with more than 98.8% of the solar system’s mass. Nuclear fusion in its core powers the sun. The enormous heat and pressure generated within the sun’s centre, fusing hydrogen into helium and releasing electromagnetic energy, can take hundreds of thousands of years to move from the core, where the temperature reaches 15 million degrees Celcius, to the sun’s visible surface which is 5600 degrees Celcius. Magnetic fields twisting in its body pull streamers of gas far into space (solar flares). The flare ejects clouds of electrons, ions, and atoms through the corona of the sun into space. These clouds typically reach Earth a day or two after the event. The Sun dominates the solar system not only through its gravitational influence, which extends up to 200,000 astronomical units away, but also through its solar wind of charged particles, which reach beyond 100 astronomical units (far past Pluto). An astronomical unit (AU) is 149,597, 871 kilometres, or roughly the same distance between Earth and the Sun. The Planets The planets where shaped by the nearby sun and ended up rocky, small and dense, with at least one, Earth, orbiting at just the right distance to hold on to watery oceans and host the chemical of life. The planets can be divided up into two groups of four. Closest to the sun are the four inner planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. The inner planets are compact and rocky with just three moons between them. They are called terrestrial planets because they are more or less earth-like. All of them have secondary atmospheres (produced after their formation) and at least three of them planets may once have had oceans; Venus, whose seas may have been boiled off by the greenhouse effect; Mars, whose once liquid oceans might now be frozen under its surface and Earth, the Blue Planet, orbiting at just the right distance from the sun to maintain liquid water on its surface. Far from the sun, beyond the asteroid belt, orbit the four gas giants - Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. These four outer planets are huge and vaporous, possessing rings and more than 160 natural satellites between them. Mercury Mercury is just 4878 kms in diameter, making it the smallest of the planets. Due to Mercury’s off-centre orbit of the sun, bringing it as close as 46 million kms to the sun at its closest point and as far as 69.82 million kms from the sun at its furthest point, the planet see great extremes in temperature, going from highs of 427 degrees celcius to lows of -173 degrees celcius. Mercury has no natural satellites. Venus In size, Venus is a near match to Earth, at 12,103 kms in diameter, only 653 kms smaller than earth. Its mass is only slightly less than that of Earth and its density and surface gravity are also close to our own planet. However, Venus is, in fact, a smoggy furnace beneath a crushing acidic atmosphere with an average surface temperature of 462 degrees Celcius, making it the hottest planet in the solar system. It has no natural satellites. Venus is the brightest object in the sky from Earth other than the sun and moon and is often referred to as the Morning or Evening star. Earth Earth is the largest of the four terrestrial planets, at 12,756 kms in diameter. Earth is not completely spherical but slightly wider at the centre because of its rotation. Earth is denser than other rocky planets and has a higher surface gravity. It is the only planet with liquid water on its surface. Its surface is varied and dynamic, consisting of crustal plates slowly shifting under a stable, shallow, moist atmosphere. Protecting Earth from radiation is the magnetosphere, a magnetic field thousands of miles long. Earth’s only moon circles the planet at a distance of 384,400 kms away. Mars Known as the red planet, Mars is the fourth planet from the sun and the outermost of the rocky planets, orbiting at an average distance of 227.9 million kms from the sun. It is roughly half the size of Earth and is now a dry, barren planet with a surface marked by large canyon systems and huge extinct volcanos, its most famous being Olympus Mons, the largest volcano in the solar system. Vast dust storms whip around the planet and clouds and falling snow have been seen by spacecraft sent to explore its surface. Like Earth, Mars has seasons and ice caps and evidence suggests that liquid water flowed across the Martian surface billions of years ago. Mars has two moons, Phobos and Deimos, both very small moons with the largest, Phobos, being only 27 kms long and 22 kms wide. Jupiter Within the solar system, Jupiter is second only to the Sun is size and mass. The gas giant, at 142,984 kms in diameter, and could hold 1300 Earths. It is almost two and a half times the combined mass of the other 7 planets put together. Jupiter takes almost 12 years to circle the Sun but rotates once every 9.9 hours, so fast that it is more egg shaped than sphere. Composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, like the sun, it has no real surface but a deep and windy atmosphere over a liquid hydrogen ocean. Jupiter is not just a planet, but a planet-moon system with 63 natural satellites, one of which, Ganymede, is the largest moon in the solar system. Jupiter’s atmosphere is affected by colossal, oval shaped storms whipped up by the planets internal heat and very fast rotation. The largest of these storms is the Great Red Spot which is about twice the size of Earth and has been raging for more than 350 years. Saturn Saturn, seen as one of the most beautiful planets with its rings, made from billions of ice particles sculpted into multiple bands by the gravity of some of Saturn’s moons. It has 61 natural satellites, the largest of which is Titan, the only satellite in the solar system to possess a thick atmosphere and, apparently, liquid lakes (of methane and ethane) on its surface, possible havens for life. Saturn is 1.4 billion kms from the sun and is the second largest planet in the solar system after Jupiter. It consists almost entirely of the lightest elements, hydrogen and helium and as a result is the least dense planet in the solar system. Uranus One of the two ice giants, Uranus is the third largest planet in the Solar System and lies twice as far from the sun as Saturn (2.9 billion kms). Neptune is pale blue in colour, which comes from the methane in its atmosphere. It is featureless with a sparse ring system and 27 moons. As a result of what is thought to have been a collision with a planet-sized body not long after it formed, Uranus’s spin axis is tipped over by 98%, giving it the appearance of moving along on its orbital path on its side, with its moon encircling it from top to bottom. Its spin is retrograde – meaning it rotates in the opposite direction to that of most other planets. Neptune The second of the two ice giants, Neptune is the coldest planet in the Solar System. Neptune is 4.5 billion kms from the Sun and takes 163.7 Earth years to orbit the Sun, so has only completed one circuit since its discovery in 1846. Neptune has a core of rock and metal, surrounded by a liquid layer of water, ammonia and methane. Above this is a hydrogen dominated atmosphere affect by huge wind speeds of up to 2000 kms per hour – the highest wind speed found on any planet. It has 13 moons, the largest of which is Triton. SCIENCE Inventions An A – Z of some inventions that changed the world Abacus, AD190 Use of the abacus, with its beads in a rack, was first documented in China in about AD190, but the word dates to much earlier calculating devices. ‘Abacus’ derives from the Hebrew ibeq, meaning to ‘wipe the dust’ or from the Greek abax, meaning ‘board covered with dust’, which describes the first devices used by the Babylonians. The Chinese version was the fastest way to do sums and in the right hands, can still outpace electronic calculators. Archimedes Screw, c.700BC Purportedly devised by the Greek physicist Archimedes in the 3rd century BC to expel bilge water from creaking ships, the screw that bears his name in fact predates Archimedes by about 400 years. Recent digs have established that earlier screws, which are capable of shifting water uphill, were used in the Hanging Gardens of Babylon in the 7th century BC. So effective is the device, it is still used today in several sewage plants and irrigation ditches. Aspirin, 1899 Little tablets of acetylsalicylic acid have probably cured more minor ills than any other medicine. Hippocrates was the first to realise the healing power of the substance – his related ancient Greek treatment was a tea made from willow bark, and was effective against fevers and gout. Much later, in turn-of-the-century Germany, chemist Felix Hoffman perfected the remedy on his arthritic father, marketing it under the trade name Aspirin. Barcode, 1973 Barcodes were conceived as a kind of visual Morse code by a Philadelphia student in 1952, but retailers were slow to take up the technology, which could be unreliable. That changed in the early 1970s when the same student, Norman Woodland, then employed by IBM, devised the Universal Product Code. Since then, black stripes have appeared on almost everything we buy. Battery, 1800 For the battery we must thank the frog. In the 1780s, the Italian physicist Luigi Galvani discovered that a dead frog's leg would twitch when he touched it with two pieces of metal. Galvani had created a crude circuit and the phenomenon was taken up by his friend, the aristocratic Professor Alessandro Volta, whose voltaic cells stacked in a Voltaic pile amazed Napoleon. The pile was also the first battery, whose successors power more than a third of the gadgets on this list. Biro, 1938 Had the Hungarian journalist Laszlo José Biró kept the patent for the world's first ballpoint pen, his estate (he died in 1985) would be worth billions. As it happened, Biró sold the patent to one Baron Bich of France in 1950. Biró's breakthrough had been to devise a ball-bearing nib capable of delivering to paper the smudge-resistant ink. Today around 14 million Bic "Biros" are sold every day, perhaps making the pen the world's most successful gadget. Camera, 1826 British William Talbot, inventor of one of the earliest cameras (Joseph Nicéphore Niépce had produced the earliest surviving photograph on a pewter plate in 1826), was inspired by his inability to draw. He described one of his sketches as "melancholy to behold", wishing for a way to fix on paper the fleeting photographic images that had been observed for centuries using camera obscura. His early developing techniques in the late 1830s set the standard for decades – he invented the negative/positive process – and photography began to take off, helped in large part, in 1888, by George Eastman's Kodak, the first camera to take film. CD, 1965 For the US inventor James Russell, the crackly sound of vinyl ruined music, so he patented a disc that could be read with a laser. Philips and Sony picked up the trail in the early 1970s, when they perfected the Compact Audio Disc or CAD, later shortened to CD. The first discs appeared in the early 1980s and could play 74 minutes, on the insistence of Sony chief Akio Morita, who stipulated one disc could carry Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. Clockwork radio, 1991 With the wind-up radio, not only did deprived areas of the developing world get access to public information, but we were gifted a true legend of invention. British Trevor Bayliss, a former professional swimmer, stuntman and pool salesman, devised the contraption after being horrified by reports from Africa that important information wasn't getting through to people outside the cities. Compass, 1190 Forced to rely on natural cues such as cliffs or spits of land, as well as crude maps and the heavens, early mariners would get hopelessly lost. Desperate for something more reliable, sailors in China and Europe independently discovered in the 12th century lodestone a magnetic mineral that aligned with the North Pole. By 1190, Italian navigators were using lodestone to magnetise needles floating in bowls of water. The device set humanity on the course to chart the globe. Digital camera, 1975 There could be no digital camera without the charge-coupled device (CCD), the "digital film" that captures images electronically. Developed in 1969, the widget allowed the Kodak engineer Steven Sasson to build the first digital camera, which resembled a toaster. The first, horribly blurry snap (of a female lab assistant) he took boasted just 0.01 megapixels and took almost a minute to record and display, but in those 60 seconds, Sasson had transformed photography – today digital cameras have all but killed off film and made photographers of us all. Dynamite, 1867 Few inventions, save perhaps the atomic bomb, can claim to have shaken the world in quite the same way as nitroglycerine. And few inventions can have claimed so many lives. The first to succumb to the explosive force of Dynamite was the inventor's brother; Alfred Nobel's youngest sibling perished when an early experiment to stabilise nitroglycerine by adding a chalky material called kieselguhr, went horribly wrong. In 1896, Nobel used his Dynamite fortune to endow the Nobel Prizes. Fibre optic cable, 1966 In an experiment requiring nothing more complicated than two buckets, a tap and some water, the Irish scientist John Tyndall in 1870 observed that a flow of water could channel sunlight. Fibre optics – tubes of glass or plastic capable of transmitting signals much more efficiently than traditional metal wire – operate under the same principles and were perfected by Charles Kao and George Hockham in 1966. Today, thousands of miles of cables link all corners of the globe. Flushing toilet, 1597 Sir John Harrington, author, courtier and godson to Queen Elizabeth I, is the true inventor of the flush toilet. The miscredited Thomas Crapper, whose name helped build the urban myth that has surrounded him for centuries was beaten to the invention by Harrington who installed lavatories for the Queen at Richmond in the late 16th century. Fridge, 1834 The greatest kitchen convenience was the death of the greengrocer, allowing harried professionals to keep perishables "fresh" for days at a time. But few people (greengrocers aside) would bemoan their invention. Jacob Perkins was the first to describe how pipes filled with volatile chemicals whose molecules evaporated very easily could keep food cool, like wind chilling your skin after a dip in the sea. But he neglected to publish his invention and its evolution was slow – fridges would not be commonplace for another 100 years. Internal combustion engine, 1859 It may have fallen firmly out of favour in today's green-aware world, but the importance of the internal combustion engine is impossible to overstate. Without it, we could not drive, fly, travel by train, build factories, motor across oceans, trim our lawns ... the list is endless. Credit for the first working internal combustion engine goes to the Belgian inventor Étienne Lenoir, who converted a steam engine in 1859. It boasted just one horsepower and was woefully inefficient, but spawned the billions of engines that have been built since. iPod, 2001 Can it really be just six years since the now ubiquitous slab of sleek white plastic and polished steel burst on to the gadget scene and helped to revolutionise the music industry? Conceived by Apple's British design luminary, Jonathan Ive, the iPod, the largest of which can store more than 30,000 songs, has sold an astonishing 110m units in 14 incarnations (that's an average 2,000 iPods an hour). Laser, 1960 Laser stands for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. It was Albert Einstein who laid the foundations for its development, when in 1917 he said atoms could be stimulated to emit photons in a single direction. The phenomenon was first observed in the 1950s and the physicist Theodore Maiman built the first working laser in 1960. His device was based around a ruby crystal that emitted light "brighter than the centre of the sun". Lead pencil, 1564 Any schoolboy worth his salt knows pencils do not in fact contain potentially poisonous lead. And they never did; the pencil arrived with the discovery in 1564 in Borrowdale, Cumbria, of a pure deposit of graphite, then thought to be a type of lead. A year later, the German naturalist Conrad Gesner described a wooden writing tool that contained the substance. Nicolas Conté perfected the pencil more than a century later by mixing graphite with clay and gluing it between two strips of wood. Light bulb, 1848 So new-fangled was the light bulb in the 19th century, it came with a warning: "This room is equipped with Edison Electric Light. Do not attempt to light with match. Simply turn key on wall by the door. The use of electricity for lighting is in no way detrimental to health, nor does it affect the soundness of sleep." Joseph Swan in fact developed a bulb before Edison, but the pair later joined forces and share credit for creating the gadget we perhaps take for granted more than any other. Microchip, 1958 It is impossible to sum up how much these tiny slivers of silicon and metal have transformed our lives. They feature in everything from toys to tanks and motorbikes to microwaves but when, in 1952, the British engineer Geoffrey Dummer proposed using a block of silicon, whose layers would provide the components of electronic systems, nobody took him seriously and he never built a working prototype. Six years later, US engineer Jack Kilby took the baton and built the world's first monolithic integrated circuit, or microchip. Microscope, 1590 When the British polymath Robert Hooke published his 1665 masterpiece, Micrographia, people were blown away by its depictions of the miniature world. Samuel Pepys called it "the most ingenious book that I ever read in my life". Until then, few people knew that fleas had hairy legs or that plants comprised cells (Hooke coined the term "cell"). Zacharias Janssen, a Dutch spectacle maker, had invented the first microscope in 1590, although it was then regarded as a novelty rather than a revolution in science. Mobile phone, 1947 There are more than two billion mobile phones in the world, and the EU is home to more "cells", as the American's call them, than people. It is difficult to quantify the economic and social impact of the device – of all the gadgets in the average person's arsenal, it is surely the one we would be worst off without. Those who disagree can blame Bell Laboratories for their invention; the firm introduced the first service in Missouri in 1947. Widespread coverage in Britain did not begin until the late1980s. PC, 1977 The computers IBM were producing for businesses as early as the late 1950s cost about $100,000 (almost £500,000 today), so the idea of one in every home remained a dream. But that changed in the 1970s when a group of chipwielding geeks based in California began tinkering in garages. One of the brightest techies operating in what is now dubbed Silicon Valley was Steve Jobs, whose Apple II, launched in 1977, was the first consumer PC to resemble the machines that went on to transform our lives. Pneumatic tyre, 1845 Back when cars relied on real horse-power and bicycles weighed a ton, travellers were forced to endure bone-jarring rides over the bumps and potholes of the nation's primitive roads. Cue Robert Thomson, a civil engineer who realised the potential of air to soften the way. In 1845, he patented the use of pneumatic leather tyres on bikes. In 1888, a Scottish vet called John Dunlop devised the more durable rubber inner-tube model that helped inflate the age of the automobile. Printing press, 1454 For the large part of modern civilisation, the written word reigned supreme as the only means of communication. The Chinese were the world's first printers – they practised block printing as early as 500 AD – but a German goldsmith called Johannes Gutenberg was the first to construct a press that comprised moveable metal type, which, when laid over ink, could print repeatedly on to paper. In 1454 he used the revolutionary system to print 300 bibles, of which 48 copies survive, each worth millions of pounds. Radio, 1895 We were nearly denied radio by an uncharacteristic lack of foresight shown by one Heinrich Hertz who, while demonstrating electromagnetic waves in 1888, told his students, "I don't see any useful purpose for this mysterious, invisible electromagnetic energy." Fortunately, Alexander Popov, a Russian, and the Italian-Irish inventor Guglielmo Marconi, saw the potential in the technology and separately sent and received the first radio waves. Marconi sent the first transatlantic radio message (three dots for the letter "S") in 1901. SMS, 1992 Linguist purists H8 txtspk. The Short Message Service (SMS) has developed the thumbs of a generation of communicators who have devised their own shorthand, textspeak, to stay in touch. The British engineer Neil Papworth sent the first (unabbreviated) text 15 years ago. It read: "MERRY CHRISTMAS". Their popularity exploded in the late 1990s and now in the UK alone we send millions every day (a record 214 million on New Year's Eve). Telephone, 1876 Frenchman Charles Bourseul first proposed transmitting speech electronically in 1854, but he was ahead of his time and it took another six years before Johann Reis used a cork, knitting needle, sausage skin and a piece of platinum to transmit sound, if not intelligible speech (that took another 16 years). Elisha Gray and Alexander Graham Bell raced to make the first working phone in the 1870s, Bell winning in a photo-finish. Today there are 1.3 billion phone lines in use around the world. Television, 1925 Television has helped connect people around the world, entertained billions, and kept generations of children occupied on lazy Sunday mornings. Not that CP Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian, was impressed. He said in 1920: "Television? The word is half Greek and half Latin. No good will come of it." Scotsman John Logie Baird first demonstrated TV to the public in 1925. The internet, 1969 The simplest way to illustrate the inestimable impact of the internet is to chart the growth in the number of people connected to it: from just four in 1969 to 50,000 in 1988; a million by 1991 and 500 million by 2001. And today - 1.2 billion, or 19 per cent of the world's population. Conceived by the US Department of Defense in the 1960s, the internet, together with the World Wide Web, invented in 1989 by Brit techie, Tim Berners-Lee, has shrunk the world like no other invention. Thermometer, 1592 It is difficult to place the thermometer in the history of modern invention; it is one of those devices that would inevitably appear – the product of no single mind. Galileo Galilei is most commonly credited, but his clumsy air thermometer, in which a column of air trapped in water expanded when warmed, was the culmination of more than 100 years of improvement. The classic mercury-in-glass thermometer, still in use today, was conceived by Daniel Fahrenheit in the 1720s. Wheel, 3500BC The wheel surely deserves a place near the top of any "greatest inventions" list; a post-industrial world without it is inconceivable. Its invention was perhaps inevitable, but it came later than it might have done; several civilisations, including the Incas and the Aztecs did pretty well without wheels. The earliest evidence of a wheel – a pictograph from Sumeria (modern day Iraq) – dates from 3500BC; the device rolled West soon after that. Zip, 1913 Credit for the device's invention goes to Gideon Sundback. In 1913, the Swedish engineer made the first modern zip to fasten high boots. Look at your clothes and, chances are, the zip that keeps your valuables in place started life in a factory in the Qiaotou, China. Qiaotou's zip plants manufacture an astonishing 80 per cent of the world's zips, churning out 124,000 miles of zip each year (enough to stretch five times round the globe or half way to the moon). SCIENCE The Elements A chemical element is a pure chemical substance consisting of one type of atom distinguished by its atomic number, which is the number of protons in its nucleus. Elements are divided into metals, metalloids, and non-metals. The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. He developed his table to illustrate periodic trends in the properties of the then-known elements. Mendeleev also predicted some properties of then-unknown elements that would be expected to fill gaps in this table. Most of his predictions were proved correct when the elements in question were subsequently discovered. Below are some of the most common elements with their chemical symbol and atomic number. Element Atomic Number Chemical Symbol Hydrogen 1 H Helium 2 He Carbon 6 C Nitrogen 7 N Oxygen 8 O Neon 10 Ne Sodium 11 Na Magnesium 12 Mg Aulminium 13 Al Silicon 14 Si Sulphur 16 S Chlorine 17 Cl Potassium 19 K Calcium 20 Ca Chromium 24 Cr Iron 26 Fe Copper 29 Cu Silver 47 Ag Tin 50 Sn Platinum 78 Pt Gold 79 Au Mercury 80 Hg Lead 82 Pb SCIENCE MEDICAL ADVANCES AND DISCOVERIES Below are some of the most important medical advances and discoveries that changed our world Vaccination The discovery of vaccination has helped to greatly reduce some of the world’s deadliest epidemics and diseases, from cholera, influenza and measles, to the bubonic plague. Edward Jenner, an English country doctor, performed the first vaccination against smallpox in 1796 after discovering that inoculation with cowpox provides immunity. Jenner formulated his theory after noticing that patients who work with cattle and had come into contact with cowpox never came down with smallpox when an epidemic ravaged the countryside in 1788. Thanks to vaccination, we no longer have to deal with some of the world’s deadliest and most infectious diseases, which have plagued humankind for millennia. Germ Theory Germ theory (discovered by French chemist Louis Pasteur) allowed our scientists to find the major causes behind disease, and created a whole new understanding of why cleanliness was important, as opposed to the old practice of surrounding oneself with bad smells to ward off bad influences. At that time, the origin of diseases such as cholera, anthrax and rabies was a mystery. The discovery of germ theory helped bring the knowledge of the importance of sanitation, and is one of the biggest factors in extending human life by prevention of disease. Penicillin Germ theory might have been the discovery of bacteria, but the discovery of penicillin was the moment that the medical profession finally had a way to fight back against infections that would have once cost people their lives. Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, then Howard Florey and Boris Chain isolate and purify the compound, producing the first antibiotic. Fleming's discovery comes completely by accident when he notices that mould has killed a bacteria sample in a petri dish that is languishing in his lab's sink. Fleming isolates a sample of the mould and identifies it as Penicillium notatum. With controlled experimentation, Florey and Chain later find the compound cures mice with bacterial infections. Penicillin became the starting point for a whole string of antibiotics. This new way of treatment meant that amputations were significantly reduced, gum infections could be treated, and infections of the blood were no longer fatal. Anesthetics Anesthetics are easily one of the most important medical advances in surgical operations. Between 1842 and 1846 several scientists discovered that certain chemicals can be used as anesthetics, making it possible to perform surgery without pain. The earliest experiments with anesthetic agents — nitrous oxide (laughing gas) and sulfuric ether — were performed mainly by dentists. By preventing pain during surgery, surgeons were given the ability to work in completely new ways with the human body, with a lower chance from complications such as shock, allowing them to perform more complex and intricate surgical procedures. X-Ray In 1895, Wilhelm Roentgen accidentally discovered X-rays as he conducts experiments with the radiation from cathode rays (electrons). He notices that the rays are able to penetrate opaque black paper wrapped around a cathode ray tube, causing a nearby table to glow with florescence. His discovery revolutionizes physics and medicine, earning him the first-ever Nobel Prize for physics in 1901. Blood Circulatory system William Harvey discovered that blood circulates through the body and names the heart as the organ responsible for pumping the blood. His groundbreaking work, published in 1628, lays the groundwork for modern physiology. Harvey was not able to identify the capillary system connecting arteries and veins; which were later described by Marcello Malpighi. Blood Groups Austrian biologist Karl Landsteiner and his group discovered four blood groups and developed a system of classification. Knowledge of the different blood types is crucial in performing safe blood transfusions, now a commonplace medical procedure. DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid) The initial discovery of DNA was made by the Swiss physician Friedrich Miescher. It was first called a “nuclein” because it resides in the nucleus of a cell. The first correct image of DNA was produced by James D. Watson and Francis Crick based on image diffraction by Rosalind Franklin. DNA is a person’s individual blue print and is seen as the building block of life. Insulin Frederick Banting and his colleagues discovered the hormone insulin in the 1920′s, which helps balance blood sugar levels in diabetes patients and allows them to live normal lives. Before insulin, diabetes meant a slow and certain death. Vitamins Frederick Hopkins and a few other scientists discover (in the early 1900′s) that some diseases are caused by deficiencies of certain nutrients, later called vitamins. Through feeding experiments with laboratory animals, Hopkins concluded that these “accessory food factors” are essential to health. The Human Retrovirus (HIV) Competing scientists Robert Gallo and Luc Montagnier separately discovered a new retrovirus later dubbed HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), and identify it as the causative agent of AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). This discovery helped in the progress towards developing drugs to help combat or slow the progress of the disease.