morality

advertisement

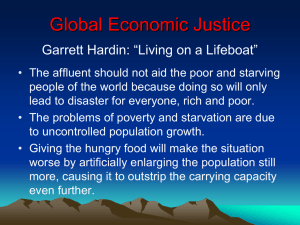

Louis P.Pojman Ethics: discovering right and wrong 1 Ethical theories ethical theory the locus of value deontological the (kind) of act teleological the outcome i.e. consequences virtue the character Pojman p 11-12 2 Normative subjects Subject Normative Disjuncts Sanctions Ethics Right and wrong, as defined by conscience or reason Conscience – praise and blame, reputation Religion Right and wrong (sin), generally as defined by religious authority Conscience – eternal reward and punishment, due to a supernatural agent or force Law Legal and illegal, as defined by a judicial body Punishments determined by the legislative body Etiquette Proper and improper, as defined by the culture Social disapprobation and approbation Pojman p 6 3 Traits of Moral Principles 1. Prescriptivity 2. Universalizability 3. Overridingness 4. Publicity 5. Practicability Pojman p 7 4 What and how do we evaluate Domain 1.Action (the act) 2.Consequences Evaluative Terms Right, wrong, obligatory, optional Good, bad, indifferent 3.Character Virtuous, vicious, neutral 4.Motive Good will, evil will, neutral Pojman p 9 5 Types of action Right (permissible) Wrong (not permissible) Obligatory Optional Neutral Supererogatory Pojman p 10 6 The Purposes of Morality 1. 2. 3. 4. To keep society from falling apart. To ameliorate human suffering. To promote human flourishing. To resolve conflicts of interest in just ways. 5. To assign responsibility for actions. Pojman p 18 7 Ethical Relativism 1. The Diversity Thesis: there are no universal moral standards held by all societies 2. The Dependency Thesis: to act in a certain way is relative to the society 3. The Conclusion: there are no absolute or objective moral standards Pojman p 28 8 Ethical Subjectivism »Solipsism »Atomism »Escapism Pojman p 33 9 Ethical Conventionalism • Conservative • Totalitarian • Intolerant Pojman p 41 10 The doctrine of natural law 1. Morality is a function of human nature. 2. Reason can discover valid moral principles by looking at the nature of humanity and society. Pojman p 45 11 The key ideas of the natural law tradition 1. Human beings have an essential rational nature 2. Reason can discover the laws for human flourishing 3. The natural laws are universal and unchangeable Pojman p 47 12 The doctrine of double effect an act is morally permissible: 1. 2. 3. 4. The Nature-of-the-Act Condition The Means-End Condition The Right-Intention Condition The Proportionality Condition Pojman p 48 13 Moral absolutism and objectivism moral absolutism moral principles are nonoverridable moral norms are without exceptions Kant, act utilitarianism moral objectivism moral principles are universally valid no moral duty has absolute priority Ross Pojman p 45 14 Prima facie principles valid rules of action that one should generally adhere to but that, in cases of moral conflict, may be overridable by another moral principle. Pojman p 51 15 Minimal principles of the core morality 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Do not kill innocent people. Do not cause unnecessary pain or suffering. Do not steal or cheat. Keep your promises and honor your contracts. Do not deprive another person of his or her freedom. Do justice, treating equals equally and unequals unequally. 7. Reciprocate: Show gratitude for services rendered. 8. Tell the truth, or, at least, do not lie. 9. Help other people, at least when the cost to oneself is minimal. 10. Obey just laws. Pojman p 52 16 Justification of Moderate Objectivism 1. Human nature is relatively similar, having a common set of needs and interests. 2. Moral principles are functions of human needs and interests, instituted by reason. 3. Some moral principles will meet human needs and promote human interests better than others. 4. These principles can be said to be objectively valid principles. 5. Therefore an objectively valid set of moral principles is applicable to all humanity. Pojman p 53-54 17 The attraction of ethical relativism 1. The option that absolutism and relativism are the only alternatives. 2. Objectiviam is confused with realism. 3. The move from descriptive cultural relativism to normative ethical relativism. 4. Drive to moral nihilism and relativism because of the decline of religion in Western society. 5. As metaethics so ought also ethics be morally neutral (amoral). Pojman p 56-58 18 Egoism The doctrine that it is morally right always to seek one's own self-interest without regard for others. Pojman p 71 19 Four types of egoism 1.Psychological egoism We have no choice butto be selfish. 2.Personal egoism The state of being selfish by choice 3.Individual ethical egoism Everyone ought to serve my best interest 4.Universal ethical egoism Everyone ought always to do those acts that will best serve own best self-interest Pojman p 65 20 Ethical egoism 1. The Economist Argument individual selfinterest in a competitive marketplace produces a state of optimal goodness for society at large 2. The Argument for the Virtue of Selfishness altruism is suicidal 3. The Hobbesian Argument because we are predominantly psychological egoists it is morally permissible to act entirely out of self-interest Pojman p 72-74 21 A critique of ethical egoism 1. The Inconsistent Outcomes Argument morality is not a guide to action 2. The Publicity Argument egoist must act alone, atomistically or solipsistically in moral isolation 3. The Paradox of Egoism in order to reach the goal of egoism on emust give up egoism and become (to some extent) an altruist 4. Counterintuitive Consequences helping others at one's own expense is morally wrong Pojman p 76-78 22 Altruism The theory that we can and should sometimes act in favor of others' interests. Pojman p 66 23 Four types of altuism 1.Psychological altruism We have no choice butto be unselfish. 2.Personal altruism The state of being unselfish by choice for reciprocal cooperation 3.Individual ethical altruism I ought to serve everyone’s best interest 4.Universal ethical altruism Everyone ought always to sacrifice own happiness for the good of others From Pojman chp 4 Noormägi 24 Reciprocal Altruism No duty to serve those who manipulate us, but willing to share with those willing to cooperate. Pojman p 80 25 Axiology -10..........................0.........................+10 negative neutral positive evil/disvalue (value neutral) highest value Pojman p 85 26 Value (to be of worth) intrinsic worthy in itself (because of its nature) instrumental creation of choosers (because of its consequences) Pojman p 86-87 27 Plato's question Do we desire the Good because it is good, or is the Good good because we desire it? Pojman p 85 28 Schema of the Moral Process ACTIONS Failure: weakness of will leads to guilt DECISIONS Failure: perverse will leads to guilt JUDGMENTS Weighing Failure: error in application PRINCIPLES VALUES Normative question: What ought I do? Objects of desire or objects existing independently of desires FORMS OF LIFE Hierarchies of beliefs, values, and practices; cultures or ways of life RATIONAL JUSTIFICATION . Of ethical theories 1. Impartiality 2. Freedom 3. Knowledge Pojman p 95 29 The Relation of Value to Morality Values are rooted in cultural constructs (in whole forms of life) and are the foundation for moral principles upon which moral reasoning is based. Pojman p 96 30 Views of happiness Absolutists Subjectivists Combinational (Objectivism) A single ideal for human nature - harmony of the soul - is to live according to reason Happiness is in the eyes of the beholder if I feel happy, I am happy There is a plurality of life plans open to each person - the person is the autonomous chooser of a plan, but there are primary goods and unless these goods are present, the life plan is not an authentic manifestation of an individual's own selfhood Pojman p 96-97 31 Plan-of-life 1. an integrated whole 2. freely chosen by the person 3. possible to realize Pojman p 97 32 The happy life Action Participation in our own destiny, not being entirely passive Freedom To make choices, not being determined Character To be someone, have identity Relationships To love and be loved Pojman p 99 33 Standard of happy life exclude being severely retarded, a slave, a drug addict include being a deeply fulfilled, autonomous, healthy person Pojman p 100 34 Happiness is a life in which exist free action (including meaningful work), loving relations, and moral character, and in which the individual is not plagued by guilt and anxiety but is blessed with peace and satisfaction. Pojman p 100 35 Traditional morality advise who criticism Let your conscience be your guide common sense conscience is a function of upbringing Do whatever is most loving St. Augustine no help in a conflict of interests Do unto others as you would have them do unto you the Golden Rule we are different Pojman p 105-106 36 Utilitarianism “The Greatest happiness for the greatest number” Pojman p 107 37 Punishment how why purpose retribution justice defensive proportional threat preventive Pojman p 109 38 Hedonic calculus make quantitative measurements and apply the principle impartially Pojman p 110 39 Criteria of pleasure and pain »intensity »duration »certainty »nearness »fruitfulness »purity »extent Pojman p 110 40 Moral experts Those who have had wide experience of the lower and higher pleasures almost all give a decided preference to the higher type. Pojman p 111 41 Act-Utilitarianism An act is right if and only if it results in as much good as any available alternative. Pojman p 112 42 Rule-Utilitarianism An act is right if and only if it is required by a rule that is itself a member of a set of rules whose acceptance would lead to greater utility for society than any available alternative. Pojman p 113 43 Negative responsibility we are responsible not only for the consequences of our actions (doing), but also for the consequences of our non-actions (allowing) Pojman p 114 44 3 kinds of consequences consequence good, bad, indifferent actual absolutely expected objectively intended subjectively Pojman p 117 45 The strengths and weaknesses of utilitarianism strengths: • an absolute system with a single priciple with a potential answer for every situation; • morality has the substance: promoting human flourishing. weaknesses: • there are two superlatives in one principle either the greatest pleasure or to the greatest number; • the problem of knowing the comparative future consequences of actions. Pojman p 115-117 46 External objections to utilitarianism 1. no rest 2. absurd implications 3. violates integrity 4. neglects justice 5. contradicts notion of publicity Pojman p 118-120 47 Man and morality Is morality made for man, or is man made for morality? Pojman p 124 48 Deontological systems actdeontologism normdeontologism intuitionism decisionism (illumination)(existentsialism) normnormintuitionism rationalism Pojman p 131-133 49 Weaknesses of act-deontologism 1. There is no way for any arguments with an intuitionist. 2. Rules are necessary also to moral reasoning. 3. Because different situations share common features, it is inconsistent to prescribe different moral actions. Pojman p 131-132 50 Prima facie principles conditional self-evident a plural set not absolute duties actual the intuition decides in context Pojman p 1133/145 51 Prima facie duties » » » » » » » Promise-keeping Fidelity Gratitude for favors Beneficence Justice Self-improvement Non-maleficence Pojman p 133-134 52 Intuition is internal perception that both discovers the correct moral principles and applies them correctly Pojman p 133 53 Influences on Kant’s ethical thinking • pietism: the good will as the sole intrinsic good in life • Rousseau: human dignity as the primacy of freedom and autonomy • rationalism versus empiricism innate ideas versus tabula rasa Pojman p 135-136 54 Kant on morality Morality is ground on our rational will reason is sufficient for establishing the moral law as transcendent and universally binding on all rational creatures. Pojman p 137 55 Empiricism moral principles feelings and desires human nature All knowledge and justified belief is based in experience. Pojman p 136 56 The categorical imperative Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it would become a universal law”. Pojman p 139 57 The Golden Rule Do unto others as you would have them do unto you Pojman p 106 58 The Principle of Ends So act as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of any other, in every case as an end and never as merely a means”. Pojman p 146 59 The Principle of Autonomy Every rational being is able to regard oneself as a maker of universal law. Pojman p 149 60 Kant and religion the unconditional worth and equal dignity of humanity, and natural purposes in nature and human nature guarantees the ultimate justification of morality but that presupposes the ideas of • God, who enforces the moral law and rewards moral persons in proportion • immortality, since "ought" implies "can“ there must be an afterlife in which we make progress. Pojman p 150-151 61 Mixed deontological ethics the principle of beneficence • One ought not to inflict evil or harm. • One ought to prevent evil or harm. • One ought to remove evil. • One ought to do or promote good. the principle of justice • Treat every person with equal respect Pojman p 152-153 62 Critique of Deontic ethical systems 1. they lack a motivational component and morality is reactive. 2. they are founded on a theological-legal model that is no longer appropriate. 3. they ignore the spiritual dimension of life and morality is just calculation. 4. they overemphasize the principle of autonomy and neglect the communal context of morality. Pojman p 159-162 63 The virtues are excellences of character, trained behavioral dispositions that result in habitual acts Pojman p 163 64 Virtue ethics Realizing the ideal type Imitating the ideal individual Pojman p 163 65 Virtues by Aristotle intellectual (may be taught directly) moral (must be lived to be learned) Pojman p 163 66 Happiness by Aristotle Moral virtues (education) and proper social institutions (health, wealth, good fortune) Pojman p 164 67 the Golden Mean virtues are a mean between excess and deficiency at the right time, toward the right objects, for the right reason, in the right manner Pojman p 164 68 Types of Relationships between Virtue Ethics and Deontic ethics 1. Pure Aretaic Ethics 2. The Standard Deontic View 3. Complementarity Ethics Pojman p 166-167 69 The Paradox of Morality Why should I be moral? 1. For the harmony of your soul. 2. God will reward or punish people. The Ultimate Question: Is the commitment to live by moral principles a decision grounded on reason or is it an arbitrary choice? Pojman p 183-184 70 Morality and Self-Interest When reason to be moral is based on self-interest, then the rational person will be an egoist and promote morality for everyone else but will violate it whenever he or she can safely do so. Pojman p 184 71 The Prisoner's Dilemma 1. Both cooperate - both benefit 2. Both cheat - both loose 3. You cooperate and I cheat - I benefit 4. I cooperate and you cheat - you benefit Pojman p 186 72 The Entropy Principle Because of limitations in resources, intelligence, knowledge, rationality and sympathy, the social fabric tends to become chaos. Morality is antientropic: it counters the set of limitations, expands our sympathies, and contributes to the betterment of the human predicament Pojman p 231 73 The benefits of the moral life • friendship • mutual love • inner peace • moral self-esteem • freedom from moral guilt A human life without the benefits of morality is not fulfilled life. The more just the political order, the more likely self-interest and morality will converge. Pojman p 188-189 74 Religion and Ethics 1. Does morality depend on religion? a. morality depends on divine will b. reasons for action are independent 2. Is religious ethics essentially different from secular ethics? a. religion is irrelevant (Kant) or inimical to morality (secularists) b. religion enrich morality Pojman p 193 75 The Divine Command Theory 1. Morality originates with God. 2. Moral rightness means “willed by God”. 3. Therefore no further reasons for action are necessary. Pojman p 194 76 Criticism of religious morality 1. If good means "what God commands," then it is merely the tautology: "God commands us to do what God commands us to do." 2. Religious morality is arbitrary: if there are no constraints on what God can command, then anything can become a moral duty. Pojman p 196 77 Humanistic Autonomy is higher-order reflective control over one’s life: rational beings can discover objective moral principles which enable human beings to flourish independently of God or revelation by using reason and experience alone. Pojman p 198 78 Religion enrich morality 1. If God exists, then good will win out over evil. 2. If God exists, then cosmic justice reigns in the universe. 3. If theism is true, then moral reasons always override nonmoral reasons. 4. If theism is true, then God loves and cares for us – his love inspires us. 5. If God created us in his image, then all persons are of equal worth. Pojman p 202-204 79 Religion and motive 1. God is holy 2. God rewards 3. God loves us 80 Weaknesses of religious morality 1. Religion may be used as a powerful weapon for harming others. 2. The arguments for God's existence are not obviously compelling. Pojman p 204-205 81 Civil religion • scientism • capitalism • nationalism W. Beach 82 Is Fact refer to what is signified by empirically verifiable statements (some object or state of affairs exists) Ought Value refer to what is signified by an evaluative sentence (we are evaluating or apprising something) Pojman p 208-209 83 The Naturalistic Fallacy 1. Fact 2. Therefore, value. Pojman p 212 84 Moore’s intuitionism 1. The Humean Thesis (Ought statements cannot be derived from is statements) 2. The Platonic Thesis (Basic value terms refer to nonnatural properties) 3. The Cognitive Thesis (Moral statements are true or false; they are objective claims about reality, which can be known) 4. The Intuition Thesis (Moral truths are discovered by the intuition; they are self-evident upon reflection) Pojman p 216 85 Logical Positivists the meaning of a sentence is found in its method of verification Pojman p 216 86 Noncognitivism moral statements are without cognitive content – emotivism, prescirptivism. Pojman p 218 87 Emotivism 1. Moral language is expressive of emotions or feelings, without cognitive content. 2. Moral language is imperative, not descriptive. 3. Moral language aims at persuading – influencing another person’s actions. Pojman p 218 88 Prescriptivism • moral judgments (1) are prescriptive judgments that (2) exhibit logical relations and (3) are universalizable • involve principles that allow a rational procedure in cases of conflict. Pojman p 220 89 The Logic of Moral Reasoning A valid moral argument must contain at least one ought (imperatival) premise in order to reach a moral conclusion. Pojman p 222-223 90 Criticism of Prescriptivism 1. is too broad 2. permits the trivial 3. misses the point of morality 4. no constraints on altering one's principles Pojman p 227-230 91 Fact-Value Positions Problems of Meaning Problems of justification Cognitivism [Ethical claims have truth-value and it is possible to know what it is] A. Naturalism Ethical terms are defined in factual terms; they refer to natural properties. Ethical judgments are disguised assertions of some kind of fact and thus can be justified empirically. 1. Subjective Their truth originates in individual or social decision. 2. Objective Their truth is independent of individual or social decision. B. Nonnaturalism Ethical terms cannot be defined in factual terms; they refer to nonnatural properties. Ethical conclusions cannot be derived from empirically confirmed propositions. 1. Intuitionism Intuition alone provides confirmation. 2. Religious revelation Some form of divine revelation provides confirmation. Noncognitivism [Ethical claims do not have truth-value.] A. Emotivism Ethical terms do not ascribe properties, and their meaning is not factual but, rather, emotive. Ethical judgments are not factually, rationally, or intuitively justifiable. B. Prescriptivism Ethical terms do not ascribe properties, and their meaning is not factual but, rather, signifies universal prescriptions. Ethical judgments are not factually, intuitively, or rationally justifiable, but are existentially justified. Pojman p 228 92 Neonaturalism values can sometimes be derived from facts – certain facts entail values. Pojman p 227 93 Moral objectivism moral judgments are not truths about the world, but judgments about how we ought to make the world Pojman p 235 94 Cognitivism versus Noncognitivism Cognitivism Noncognitivism Realism Naturalism Nonnaturalism (intuitionism) Supernaturalism Error TheoryMoral Skepticism Antirealism Emotivism Prescriptivism Projectivism Cognitivism: Moral principles (or judgments have truth values (they are propositions that are true or false) Error theory: Realism is the correct analysis of moral principles, but we are in error about them. There are no moral truths. This is a form of moral nihilism. Noncognitivism: Moral principles (or judgments) do not have truth values (they are pro attitudes or con attitudes, not essentially proportional). Realism: Moral facts or properties exist, hence moral principles (or judgments) are proportional and true – part of the fabric of the universe. Examples of realism are naturalism, nonnaturalism, and supernaturalism. Moral Skepticism: There may or may not be moral truths, but even if they exist, we cannot know them. Antirealism: Moral principles (or judgments) do not have truth values. There are no moral facts. Examples of antirealism are emotivism, prescriptivism, and projectivism (the view that, in making moral judgments, we project our attitudes or emotions onto the world). Pojman p 240 95 Direction of fit A proposition is true word to world A moral prescriptipon is universally valid world to word Pojman p 251 96 Moral properties are functional: to fulfil the purpose of morality – to promote human flourishing and ameliorate suffering Pojman p 244 97 Moral realism thought experiments as well as anthropological and sociological data confirm our moral theory which principles are objective guidelines for our action Pojman p 252 98 A moral minimalism calling us to adhere to a core of necessary rules in order for society to function morality is social control and defensive Pojman p 255 99 Virtue ethics The duty to grow as a moral person to take on moral responsibility, to increase competence in making moral choices to develop moral capacities to experience happiness. Pojman p 257 100 The moral hero experiences a sense of aesthetic ecstasy at accomplishing moral deeds that are out of the realm of possibility for the average moral person. Pojman p 258 101 Suggestions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Identify the problem you want to analyze. As clearly as possible, state the problem and what you intend to show. Set force your arguments in logical order, and support your premises with reasons. It helps to illustrate your points with examples or to point out counterexamples to opposing points of view. Consider alternative points of view as well as objections to your own position. Try to meet these charges and show why your position is more plausible. Apply the principle of charity to your opponent’s reasoning. That is, give his or her case the strongest interpretation possible, for unless you can meet the strongest objections to your own position, you cannot be confident that your position is the best. End your paper with a summary and a conclusion. That is, succinctly review your arguments and state what you think you’ve demonstrated. In the conclusion it is always helpful to show the implications of your conclusion for other issues. Answer the question “Why does it matter?” Be prepared to write at least two drafts before you have a working copy. Make sure that your arguments are well constructed and that your paper as a whole is coherent. Regarding style: write clearly, and in an active voice. Avoid ambiguous expressions, double negatives, and jargon. Put other people’s ideas in your own words as much as possible, and give credit in the text and in bibliographical notes whenever you have used someone else’s idea or quoted someone. Include a bibliography at the end of your paper. In it list all the sources you used in writing your paper. Put the paper aside for a day, then read it afresh. Chances are you will find things to change. When you have a serious problem, do not hesitate to contact your teacher. Pojman p 269-270 102