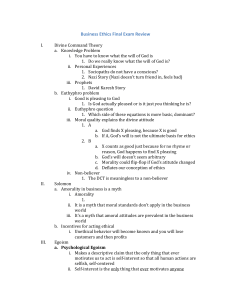

Conscience-Egoism-Kant

advertisement

PROFESSIONAL ETHICS IN SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING CDT409 Conscience, Egoism, Kant Gordana Dodig-Crnkovic Department of Computer Science and Engineering Mälardalen University 2007 1 Conscience Egoism (Psychological and Ethical) Immanuel Kant’s Deontological* Ethics * ‘deon’ = duty 2 Conscience Based on: Lawrence M. Hinman, Ph.D. Director, The Values Institute University of San Diego 3 The Seven Essential Virtues defining “Moral IQ” Empathy Conscience Self-Control Respect Tolerance Fairness Kindness Wisdom* Courage* Temperance* Justice* Integrity Responsibility Honesty 4 *Aristotles cardinal virtues The Origins of Conscience Etymology: cum + scire = to know with As science (scire) means knowledge, conscience etymologically means self-knowledge . . . But the English word implies a moral standard of action in the mind as well as a awareness of our own actions. 5 Conscience The awareness of a moral or ethical aspect to one's conduct together with the urge to prefer right over wrong. A source of moral or ethical judgment or pronouncement. Conformity to one's own sense of right conduct. The part of the superego in psychoanalysis that judges the ethical nature of one's actions and thoughts. Present in most cultures 6 The Biological Origins of Conscience Conscience biological mechanism is probably genetically determined, while its content is learnt, like language, as part of a culture. For instance, one person may feel a moral duty to go to war, another feels a moral duty to avoid war under any circumstances. Studies of brain damage show that damage to the anterior prefrontal cortex of the brain results in the reduction or elimination of inhibitions, with a radical change in behavior patterns. When the damage occurs to adults, they may still be able to perform moral reasoning; but when it occurs to children, they may never develop that ability. 7 Function of Conscience Conscience is a mechanism which judges our own actions, as being right or wrong, good or bad, and punishes us with its condemnation (disapprobation), or rewards us with its approval (approbation), according as these are, or are not, conformed to the moral standard. Conscience implies both a knowledge of our duty and an ability to perform it. 8 Characteristics of Conscience Conscience is the steering-gear and a corrective mechanism that forces us to act in accordance with our ethical norms Both negative (remorse, guilt, regret) and positive (good, clear conscience) Usually only a guide to one’s own behavior - not oriented toward judging others 9 Medieval Background Conscience is the power of reason and discernment applied to moral issues Develop an informed and sensitive conscience by living in a Christian community (defining the norm) 10 The Central Question If conscience represents the urge to conform to moral principals, what happens in case of conflicting principles? How to reconcile – Loyalty to the friend – Loyalty to society in case when there is a conflict between the two? 11 Deadlock in Conscience The case of Huck and Jim In The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Huck is faced with the dilemma of turning in his friend Jim, a runaway slave. – Huck would despise himself if he turned Jim in – Huck feels he is going against his conscience by not turning Jim into the authorities Mark Twain, THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN (Tom Sawyer'sComrade) http://users.telerama.com/~joseph/finn/finntitl.html (e-book) Mark Twain (1835-1910) (born Samuel L Clemens) 12 Unity of Virtues? Responsibly in a Professional Role Aristotle defended a strong “unity of virtue" thesis - the unity of the four cardinal virtues (wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice). Today most ethicists would agree in sharply rejecting the unity of virtue. 13 Unity of Virtues? Responsibly in a Professional Role Character is invariably riddled with "moral gaps“. Character traits are situation-sensitive, moral virtues are enormously varied (and sometimes in conflict), and both situations and personalities vary enormously. (Owen Flanagan in the Varieties of Moral Personality) 14 Unity of Virtues? Responsibly in a Professional Role Moral gaps arise not only from having some virtues (for example generosity) and lacking others (truthfulness), but in manifesting the same virtues in some contexts, roles, or dimensions of roles, but not others. 15 Unity of Virtues? Responsibly in a Professional Role Clearly a person's character is relevant to their acting responsibly in a professional role. The most important of these are humaneness, self-control, general responsibility, and honesty (both trustworthiness and truthfulness). Professionals generally are placed in positions of trust, serving an important need of client or society. The specific importance of trust is broad-based and in varying degrees open-ended. 16 Conscience in Professional Life Issues about private conscience in professional life are notoriously complex. How far should we allow private conscience to guide professional conduct when it departs from the moral consensus expressed in the relevant code of ethics? 17 Conscience in Professional Life We all agree, for example, that college professors should have great freedom to express their views. Academic freedom is central to what college professors are supposed to be. But what about an atheist philosopher who grades down a student for defending religion in an essay? The professor is wrong, of course. The question is what should we, his colleagues, do about it? Here, I think, a code of ethics is essential in setting and enforcing standards-even though codes are always vague and incomplete. 18 Conscience in Professional Life What does it require by way of setting aside personal values in order to meet professional responsibilities, to avoid greed, sexual dominance, paternalism, or conflicts of interest, and otherwise to meet minimum standards for practice of the profession? 19 The Freudian Critique of Conscience Sigmund Freud (1932) The Anatomy of the Mental Personality – ID (instinctive part, driven by pleasure and pain, fully unconscious ) – EGO (mostly conscious, deals with external reality ) – SUPER-EGO (partly conscious, is the conscience or the internal moral judge. ) 20 The Freudian Critique of Conscience Freud’s saw conscience as the voice of the superego – Initially, the internalized voice of parental restrictions – Later, the internalization of societal prohibitions – Almost exclusively negative, saying “no” to the id. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) 21 Egoism 22 Two Types of Egoism Two types of egoism: – Psychological egoism • Asserts that as a matter of fact we do always act selfishly - descriptive – Ethical egoism • Maintains that we should always act selfishly 23 Analyzing the Psychological Egoist’s Claim The psychological egoist claims that people always act selfishly or in their own self-interest. One of the earlier advocates of this view was Thomas Hobbes, who saw life as “…nasty, brutish, and short.” Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) 24 Psychological Egoism: A Common and Widespread Belief Folk psychology – There is a widespread belief that people are just out for themselves Social Darwinism: everyone is just trying to survive. Social sciences – Economics: rational agent theory Foreign policy – Belief that other nations will always act solely in terms of self-interest 25 Psychological Egoism What exactly does the psychological egoist maintain? Two possible interpretations: – #1: We act selfishly, or – #2: We act in our self-interest 26 What Does it Mean to be Selfish? If we are selfish, do we only do things that are in our genuine self-interest? – What about the chain smoker? Is this person acting out of genuine self-interest? – In fact, the smoker may be acting selfishly (doing what he wants without regard to others) but not self-interestedly (doing what will ultimately benefit him). 27 What Does it Mean to be Selfish? If we are selfish, do we only do things we believe are in our self-interest? – What about those who believe that sometimes they act altruistically? – Does anyone truly believe Mother Theresa was completely selfish? Think of the actions of parents. Don’t parents sometimes act for the sake of their children, even when it is against their narrow self-interest to do so? Mother Theresa (1910-1997) 28 Re-conceptualizing Psychological Egoism, 1 The standard view of human motivation embedded in discussions of psychological egoism sees egoism and altruism as opposite poles of a single scale: Human Motivation Egoism Altruism The premise is that an increase in egoism automatically results in a decrease in altruism, and vice versa. 29 Re-conceptualizing Psychological Egoism, 2 Instead of seeing this one a single scale, we can see egoism and altruism as two independent axes: Conceptualizing the issue in this way allows some actions to be done both for the sake of others and for one’s own sake, and avoids falling into a false dichotomy between altruism and egoism. However, an additional distinction remains to be draw. High Altruism Low Egoism High Egoism Low Altruism 30 Re-conceptualizing Psychological Egoism, 3 In addition to having two independent axes, we must distinguish between the intentions of actions and their consequences. Thus we get two graphs: Not intended to benefit self Intentions Consequences Strongly intended to help others High beneficial To others Strongly intended to benefit self Strongly intended to harm others Highly harmful to self Highly beneficial to self Highly harmful to others 31 Re-conceptualizing Psychological Egoism, 4 This double grid suggests that any given action can be ranked according to both: – Intentions – Consequences And that, for each of these two issues, each act can be ranked along two independent axes, concern/consequences for self and concern/consequences for other. 32 Ethical Egoism 33 Be My Valentine? “Love, we are repeatedly taught, consists of self-sacrifice. Love based on self-interest, we are admonished, is cheap and sordid. True love, we are told, is altruistic. But is it? “Genuine love is the exact opposite. It is the most selfish experience possible, in the true sense of the term: it benefits your life in a way that involves no sacrifice of others to yourself nor of yourself to others.” Gary Hull Valentine’s Day, 1998 Ayn Rand Institute 34 Ethical Egoism Selfishness is praised as a virtue – Ayn Rand, The Virtue of Selfishness May appeal to psychological egoism as a foundation Often very compelling for high school students Ayn Rand (1905-1982). (born Alice Rosenbaum) 35 Versions of Ethical Egoism Personal Ethical Egoism – “I am going to act only in my own interest, and everyone else can do whatever they want.” Individual Ethical Egoism – “Everyone should act in my own interest.” Universal Ethical Egoism – “Each individual should act in his or her own self interest.” 36 Altruism Unselfish concern for the welfare of others; selflessness, charity, generosity. Zoology. Instinctive cooperative behavior that is detrimental (harmful) to the individual but contributes to the survival of the species. 37 Arguments for Ethical Egoism Altruism is demeaning. Acting selfishly creates a better world. It doesn’t result in such a different world after all. demean = degrade oneself 38 Argument for Ethical Egoism: Altruism is Demeaning Friedrich Nietzsche argued that altruism was demeaning because it meant that an individual was saying that some other person was more important than that individual. Nietzsche saw this as denigrating oneself, putting oneself down by valuing oneself less than the other. Comment. Concern for the welfare of others does not mean no concern for ones own self! Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) 39 What is great in man is that he is a bridge "Man is a rope stretched between the animal and the Superman -- a rope over an abyss...What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal: what is lovable in man is that he is a transition..." Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra 40 Argument for Ethical Egoism: Acting Selfishly Creates a Better World Ethical egoists sometimes maintain that if each person took care of himself/herself, the overall effect would be to make the world a better place for everyone. – Epistemological: Each person is best suited to know his or her own best interests. – Moral: Helping others makes them dependent, which ultimately harms them. Comment. It is rational for people to solve together their common problems. Building e.g. state institutions, that exist everywhere in the world means putting energy in a common societal project that is not in the first place meant to satisfy my own personal needs. 41 Argument for Ethical Egoism: Ethical egoism doesn’t result in a different world. This argument presupposes the people in fact already act selfishly (i.e, psychological egoism) and are just pretending to be altruistic. If psychological egoism is true, then we should admit its truth and get rid of our hypocrisy. Comment. It may not make a big difference in a world of independent, strong and healthy adults, but in a world with children and people at risk or in need, they would be put in further jeopardy. 42 Criticism of Ethical Egoism Cannot be consistently universalized. (But can work in sports!). Presupposes a world of indifferent strangers. Difficult to imagine love or even friendship between ethical egoists. Seems to be morally insensitive. 43 Universalizing Ethical Egoism Can the ethical egoist consistently will that everyone else follow the tenets of ethical egoism? – It seems to be in one’s self-interest to be selfish oneself and yet get everyone else to act altruistically (especially if they act for your benefit). This leads to individual ethical egoism. Some philosophers such as Jesse Kalin have argued that in sports we consistently universalize ethical egoism: we intend to win, but we want our opponents to try as hard as they can! 44 Ethical Egoism: A philosophy for a world of strangers Some philosophers have argued that ethical egoism is, at best, appropriate to living in a world of strangers that you do not care about. 45 Egoism, Altruism, and the Ideal World Aristotle Ideally, we seek a society in which self-interest and regard for others converge—the green zone. Egoism at the expense of others and altruism at the expense of self-interest both create worlds in which goodness and self-regard are mutually exclusive—the yellow zone. No one want the red zone, which is against both self-interest and regard for others. Tocqueville’s “Self-interest rightly understood” High Altruism Kant Self-sacrificing altruism Low Egoism Not beneficial either to self or others Drug addiction Alcoholism, etc. Self-interest and regard for others converge High Egoism Self-interest at the expense of others Low Altruism Hobbes’s State of Nature, Nietzsche? 46 Sinking Titanic: Egoism vs. Altruism (Even Risks in Technical Systems) 47 Immanuel Kant The Ethics of Duty (Deontological* Ethics) * ‘deon’ = duty 48 Living by Rules Most of us live by rules much of the time. Some of these are what Kant called Categorical Imperatives. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) 49 Categorical Imperatives Always act in such a way that the maxim of your action can be willed as a universal law of humanity. --Immanuel Kant 50 The Ethics of Respect (1) One of Kant’s most lasting contributions to moral philosophy was his emphasis on the notion of respect (Achtung). 51 The Ethics of Respect (2) Respect has become a fundamental moral concept in contemporary West – There are rituals of respect in almost all cultures. Two central questions: – What is respect? – Who or what is the proper object of respect? 52 Kant on Respect “Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end.” 53 Kant on Respecting Persons Kant brought the notion of respect (Achtung) to the center of moral philosophy for the first time. To respect people is to treat them as ends in themselves. He sees people as autonomous, i.e., as giving the moral law to themselves. The opposite of respecting people is treating them as mere means to an end. 54 Using People as Mere Means The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments – More than four hundred African American men infected with syphilis went untreated for four decades in a project the government called the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male. – Continued until 1972 55 Treating People as Ends in Themselves What are the characteristics of treating people as ends in themselves? Not denying them relevant information Allowing them freedom of choice 56 Additional Cases Plant Closing Firing Long-Time Employees Medical Experimentation on Prisoners Medical Donations by Prisoners Medical Consent Forms 57 What Is the Proper Object of Respect? For Kant, the proper object of respect is the will. Hence, respecting a person involves issues related to the will-knowledge and freedom. Other possible objects of respect: – Feelings and emotions – The dead – Animals – The natural world 58 Self-Respect Is lack of proper self-respect a moral failing? The Deferential* Wife – See article by Tom Hill, “Servility and Self-Respect” *Deferential = Respectful, considerate 59 Self-Respect Aristotle and Self-Love – What is the difference between self-respect and selflove? Clearly, there is at least a difference in the affective element. 60 Self-respect, Self-regard, Self-love Self-respect: Due respect for oneself, one's character, and one's conduct. Synonyms or near-synonyms of self-esteem include: – – – – – self-love (which can express overtones of self-promotion) self-worth self-regard self-esteem self-confidence (a sometimes disparaging term which can (more than self-esteem) suggest excessive self-regard 61 The Kantian Heritage What Kant Helped Us to See Clearly The Admirable Side of Acting from Duty – The person of duty remains committed, not matter how difficult things become. The Evenhandedness of Morality – Kantian morality does not play favorites. Respecting Other People – The notion of treating people as ends in themselves is central to much of modern ethics. 62 The Kantian Heritage Critique of Kant´s Deontology The Neglect of Moral Integration – The person of duty can have deep and conflicting inclinations and this does not decrease moral worth— indeed, it seems to increase it in Kant’s eyes. The Role of Emotions – For Kant, the emotions are always suspect because they are changeable. 63 The Kantian Heritage Critique of Kant´s Deontology The Place of Consequences in the Moral Life – In order to protect the moral life from the changing of moral luck, Kant held a very strong position that refused to attach moral blame to individuals who were acting with good will, even though some indirect bad consequences could be foreseen. The Kantian Heritage Conclusion Overall, after two hundred years, Kant remains an absolutely central figure in contemporary moral philosophy, one from whom we can learn much even when we disagree with him 64