sylls15.h1 - Geneseo Wiki

advertisement

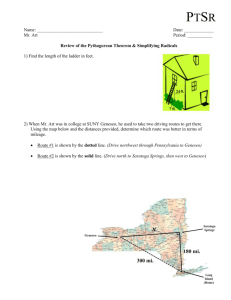

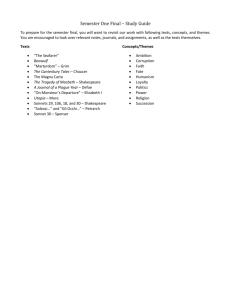

WESTERN HUMANITIES I Humanities 220 Profs. Christopher Anderson and Graham N Drake Spring 2015 TR 8.10-9.50AM Welles 138 Prof. Anderson’s Office Hours: Welles 203; office hours: TR 12-1PM (or by appointment); email: andersonc@geneseo.edu; MWFSSu: (978) 500-5017 Prof. Drake’s Office Hours: Welles 217A, ext. 5266; office hours: M 7-8PM; TR 10.15-10.45AM; W 8.45-9.15PM; virtual office hour on phone and occasionally in the office (see below): 9.30-10.30AM; email: drake@geneseo.edu and GrahamD960@aol.com; evening messages: office number; weekends: West Hartford, Connecticut (860) 2319488 OBJECTIVES It would be catastrophic to become a nation of technically competent people who have lost the ability to think critically, to examine themselves, and to respect the humanity and diversity of others….It is therefore very urgent right now to support curricular efforts aimed at producing citizens who can take charge of their own reasoning, who can see the different and foreign not as a threat to be resisted, but as an invitation to explore and understand, expanding their own minds and their capacity for citizenship. Martha Nussbaum In Western Humanities I we are learning something about ourselves that is both familiar and foreign. Our course follows the story of Western thought through certain influential texts. We will consider these works of history, philosophy, and literature in historical context; in the ways they influenced each other; in the way they shaped how we think today; in the perennial questions they raise; and in the models and metaphors they provide to help our own critical thinking, even if we're thinking something the writers of these early texts never imagined. We will see these questions, conflicts, images, and ideas as living human concerns, whether they challenge us or we challenge them. INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOMES Students in Western Humanities I will read and comprehend major texts of the Western intellectual tradition in cultural and historical context; evaluate and analyze philosophical arguments; describe specifically major historical periods; explain the structure of literary narratives and their relationships to intellectual and cultural traditions; write essays analyzing major texts or comparing two or more texts in organized, clear prose stylistically and grammatically appropriate to conventions of standard written English; discuss ideas and respond to questions about the texts, and compare and trace ideas through the tradition; formulate questions for discussion on the assigned material and the ideas they present; lead formal discussions in class and participate in small-group discussions and activities. TEXTS (in order of reading) Thucydides. The Peloponnesian War. (Penguin) Euripides. Medea. (Penguin) Plato. The Republic. (Hackett) The Bible. (Recommended translation: Revised Standard Version; (highly recommended; other translations acceptable if you already own one of them); other translations acceptable if you already own one of them) Virgil. The Aeneid. (Bantam) Augustine. Confessions. (Penguin) Boethius. The Consolation of Philosophy. (Oxford) myCourses readings on Islam. Dante. The Inferno. (Penguin) Christine de Pizan. Selected Writings. (Norton) Shakespeare. Hamlet. (Folger Edition/Washington Square Press) Additional readings from Perry. Western Civilization: A Brief History, Volume I. (Tenth Edition) (Wadsworth) You may purchase these texts at the College Bookstore. If ordering any books online, be sure to check the ISBN number and precise edition of each book. REQUIREMENTS First essay (5 pp.)—15% of grade Midterm Exam—20% of grade Second Essay (6-7 pp.)—20% of grade Final Exam—25% of grade Class participation—including general preparedness, large group discussion, small group discussions and in-class tasks, and a particular active learning component (leading one discussion question with a partner), and daily written answers to study questions—20% of grade. We will discuss the nature and format of these requirements as we proceed. AN A B C OF INFORMATION a's A semester grade of A is kind of like the Holy Grail: it is hard to achieve, but a few hardy members of the Round Table do find it. Such a grade means not merely goodness but excellence in every aspect of this course, especially in the quality of your writing (logic, development, use of evidence, persuasiveness, insight, audience appropriateness, organization, style, clarity, conciseness, diction, grammar, punctuation and spelling) and the enthusiasm of your class participation (brilliance, eloquence, judgment, graciousness, wit, evidence that you have been reading on schedule and possibly being trilingual). all i ever needed to know i learned in kindergarten In an age dominated by the discourse of the Fox News Channel, there’s a danger that America is becoming a desert for courtesy. We don't treat each other as worthy of dignity when we discuss ideas and controversial topics; we don't listen. Perhaps that’s why we all need to listen to Robert Fulghum. The forgotten lessons of early childhood are the keys to grownup civil discussion. For this class, Fulghum would probably say, “Show up on time, listen politely while others speak, wait your turn, take an active interest, take your nap later, clean up after yourself, leave with a smile.” Happy, well-ordered civilizations start with these tips. Note: we don’t mind at all if you bring your breakfast or tall skinny double-caff capp to class. If food or coffee doesn’t distract you but can keep you focused, then bring it along. (Note: we cannot be bribed with food, but it usually puts us in a happy mood.) A SPECIAL PLEA: We have to admit that we find it incredibly distracting when people leave during the middle of a discussion or lecture for a restroom break or other reason. Please do whatever you can to take care of personal needs before or after class (and in this class, during the five-minute midclass break). If you have a real emergency, that’s fine, but otherwise, we all need you here, so do stick around. attendance Notice how much class participation counts for under REQUIREMENTS. Obviously, class attendance makes participation possible at all. Being here helps you get into the rhythm of the course, gives you the most accurate, up to-date information, and gives you a chance to think, talk, react and consider. So “getting the notes” from someone doesn’t quite match the experience of really attending class. If you are absent (or late) when we make important class announcements (readings, schedule changes, details about papers), you are responsible for getting the information. We expect attendance as the default minimal commitment to this course. We don’t see a real reason for casual absences, and Prof Drake notes that he is notoriously unsympathetic to them. (Your future employer will be more than notoriously unsympathetic to casual absences: she will fire you.) On the other hand, we will always accept understandable excuses for absences—an illness or death of a relative or friend, or recognized religious observances (don't make up your own religion for the occasion). We prefer that you document such absences with a note from a doctor, parent, minister, etc. Note: under College guidelines, faculty are permitted to set an attendance policy for individual courses. In this class, you may take one unexcused absence. Each additional unexcused absence will mean a penalty of 25 points on class participation (for example, from 80% down to 55%. Another scenario: three unexcused absences subtracted from a class participation grade of 70% = -5%). Anyone not using the single unexcused absence will receive a bonus of 25 points on class participation. cell phones In order to reduce sudden distractions, please turn your mobile phone off during class (including vibrate mode). However, we will leave our phones on for security reasons (in case New York State’s emergency alert system needs to contact us). If it's just one of Prof Drake’s zany relatives, he’ll roll his eyes and refrain from picking up…. class participation means just that, participating, not just good attendance. Can you imagine saying that you participated in a triathlon just because you showed up and got the T-shirt? Of course not. Same thing for class. Much of your education comes from arguing and discussing and seeing if you can offer opinions that are more than marshmallow fluff. In a word, participation equals learning; and your participation teaches your fellow classmates. For suggestions on how to participate, see a's. Also, see speaking. Remember, you are the life of this party. You will receive a midterm grade for class participation to get a sense of where you stand. Keep in mind two class participation matters: 1. You and a partner (assigned during first class) must contribute one official discussion question during the semester. Rather than a simple content question (“What does Boethius talk about in Book 2 of the Consolation of Philosophy?”), this should be a legitimate discussion question that at least makes people think or even rustles up controversy (“Do Boethius' arguments about free will and the providence of God hold water?” “If most people nowadays don't think suicides and homosexuals automatically go to hell, then why read Dante?”) Formulate a simple question, too, without lots of confusing introductory material. You both should be able to keep the momentum going with your question; do not merely ask it and then stand back on the sidelines. Even more important, keep your discussion rooted in the text as much as you can. While it is often useful, even brilliant, to draw analogies between your author’s ideas and contemporary issues, fifteen discussion questions in a row asking, “Do you think this situation in X’s work is still true for today’s society?” (see peeves) get pretty monotonous. You and your partner may designate your discussion question by signing a sheet Prof Drake will post outside his office sometime on the first day of class. Sign up no later than 6PM, Wednesday, 21 January. Please email the question to both professors simultaneously at least a week before the date you will be asking your question. We may give you some advice about the question before we forward it to the class email list. The earlier you formulate a complete question, the sooner your classmates will see it and have time to think about its discussion. This schedule will mean that you'll have to read ahead, so plan accordingly. 2. Usually near the beginning of each class, we will ask you to write for five minutes about one of the study questions; you will write this in your study question booklet. Don't worry if you miss a study question on the day of an emergency absence (see attendance). Your absence will not affect your class participation grade; but remember to document the absence with a doctor's note or the like. disability accommodations If you have obtained a disability accommodation, one of us will be happy to discuss your needs confidentially. Also, if you think you should consider such accommodations, The Office of Disability Services can help. Here is their policy statement: SUNY Geneseo will make reasonable accommodations for persons with documented physical, emotional, or cognitive disabilities. Accommodations will also be made for medical conditions related to pregnancy or parenting. Students should contact Dean Buggie-Hunt in the Office of Disability Services (tbuggieh@geneseo.edu or 585-245-5112) and their faculty to discuss needed accommodations as early as possible in the semester. This statement can also be found, along with other important information about services, etc., at http://disability.geneseo.edu . email We encourage you to be in touch with us by email. This is a good way to ask questions about procedure—or, we hope even more, to ask questions of intellectual curiosity. (This makes us smile. Do it!) In the spirit of individual empowerment, we may sometimes answer your question with a question—or suggest where you can find the answer on your own. Note our email addresses at the beginning of the syllabus. Prof Drake adds, “ Since I often use my America on Line address, I strongly suggest that you always send messages to both of my email addresses simultaneously, especially on the weekends. This other address is GrahamD960@aol.com .” esl esl stands for “English for Speakers of Other Languages” or “English as a Second Language.” If you speak a language other than English, you may have issues about grammar, vocabulary, style, and composition that people who speak only English do not share. The ESL Lab in Milne can offer advice that goes beyond the expertise of tutors in the writing learning center. You can contact the Coordinator, Irene Belyakov-Goodman, at x.5328 or visit her in Erwin 217. essays The essays you write for this class will usually concentrate on the primary texts themselves. These are meant to be analytical essays (not library research reports), requiring you to reflect in a certain way on the text at hand. Use the text for relevant support of your argument. Please also consult the geneseo online guide, especially the section entitled “Conventions on Writing Papers in the Humanities” and the writing guidelines. Since Prof Drake will be grading the two essays, please consult him if you need advice about your essay; visit his office hours, email him, or phone him; also, stop by the writing learning center. extra credit You may earn extra credit by attending selected all-college lectures and writing a 2-3 page critical review that includes analysis as well as summary. Depending on the quality of your work, each report may earn you up to 30 percentage points applied to your class participation grade. Example: your class participation grade stands at 70%. You write two critical reviews, one earning 20 points, one earning 15. Your final class participation grade then stands at 105%, which will thus have additional weight in determining your semester grade. Remember, you cannot lose points writing a review, and you will expand your world besides. final exam This cumulative, comprehensive exam takes place in two parts: A take-home essay of four pages minimum will be due on Tuesday, 5 May in class. This essay will trace and compare ideas, themes, events, and/or historical personalities from texts, videos, lectures, and discussions throughout the semester. You will have a choice of essay topics. The second part of the exam begins on Friday, 8 May from 8-11AM. It will consist of ten identifications from the readings, lectures, discussions, videos, and readings from Perry; you will choose identifications from a list of 16-17 identifications. (A sample exam appears on myCourses.) While it is unlikely you will need more than 60-90 minutes to complete this part of the exam, available time will conclude at 11AM. Prof Anderson can be found in his office for the balance of any remaining time. A comprehensive exam should be eminently realizable if you are studying, reading, digesting, and thinking as we go along. Use the study questions as well as your own notes to prepare for this exam. Please bring one blue book with you. We will discuss the format of this exam and the midterm exam; Prof Anderson will grade both exams. geneseo online guide Read this helpful writing advice on the Geneseo website. The direct address is http://writingguide.geneseo.edu/. Study these guidelines and put them into practice to help you construct a good paper. In particular, see the page entitled “Conventions of Writing Papers in the Humanities” and Prof Drake’s own writing guidelines (listed under “Writing in a Discipline”). g.r.e.a.t. day G.R.E.A.T. Day (Geneseo Recognizing Excellence, Achievement, and Talent) takes place on 21 April 2015. This day combines the former HUPS (Humanities Undergraduate Paper Symposium), the Undergraduate Research Symposium in the sciences and social sciences, and other creative and scholarly activities. No classes will meet on this day, but high-quality papers from our own class may be eligible for a G.R.E.A.T Day session. In these student-run sessions, students whose papers have been accepted will read them aloud and engage in discussion with other session members and audience members. This experience is just like a regular academic conference where your professors deliver papers or chair sessions. Only the best papers are selected for G.R.E.A.T Day, so it's quite an honor. If Prof Drake writes “G.R.E.A.T Day— see me” on your paper, it means he’d like to have you apply to read it at G.R.E.A.T Day next year. Even if your paper is not accepted, nomination alone indicates that you've written a pretty terrific essay, and you should still include this on a résumé or a graduate school application. home (Prof Anderson) On Tuesdays and Thursdays, he is in Geneseo. On the other days of the week he is at his home in Brighton, NY, on the southeast border of Rochester. home (Prof Drake) This section should be called my multilocational personal life. During the middle of the week, he is in the Geneseo area. On other days (generally Thursday night through Monday morning) you can find him at home in West Hartford, Connecticut. Check the proper phone numbers at the beginning of this syllabus, and feel free about telephoning him wherever he is. His snailmail address is 56 Ironwood Road, West Hartford, CT 06117. hovering If you are hovering between two possible semester grades—say, between an A- and a B+—then I will assess your work on the whole to figure out which of the two grades to award. It is important for me to assess not only your numerical average but also how you've improved—and especially how you've contributed with your class participation. i still don't understand plato So let's talk. Come see us during our office hours, schedule an extra appointment, see us after class, phone us, email us. If you do not think you are “getting” a text or a concept, we can discuss it to see if we can come to a way to see things more clearly; we can also steer you towards books that give background information beyond the material you can find in Perry. laptops Laptops have become part of the regular culture of Geneseo. They are terrific for taking and organizing notes, following along on a website in class, making a PowerPoint presentation, or looking up information that might be part of a specific class activity. Yet part of using laptops effectively means using them with courtesy; there is such a thing as "laptop etiquette." It is impolite to disengage yourself from class by surfing the web, instantmessaging, or looking at materials inappropriate for public places. These activities may distract your classmates and make it more difficult for them to attend to what they are trying to understand, learn, and contribute to. Improper use of your laptop is also self-defeating; you’re somewhere else; you miss being engaged in the present moment; you’re missing from the rest of us. So, if you want to surf, do it later. The Web is always available to you, but the time we spend here in class is more fleeting, and it will not come again. late papers Papers are due on scheduled dates at the beginning of class unless otherwise noted. Generally, we grade late papers down—2/3 of a letter grade for every day or portion of a day that the paper is late (e.g., from Adown to B). In rare circumstances, we will accept late papers or give extensions, but your reason has to be good— death and religion are two categories we can think of off the top of our heads. midterm exam The midterm takes place on 12 March between 7.30AM and 9.45AM. The midterm will cover all readings, classroom lectures and discussions, and video presentations from the beginning of the semester through 10 March. You will have a choice of questions out of which you will construct three mini-essays of three paragraphs each. Prof Anderson will grade this exam as well as the final exam. mycourses On our myCourses page, we will post handouts for class. Please print out the handouts or download them to a laptop that you will be using for the semester. At any given time, we will ask you to refer to these handouts in class. office hours Note our office hours above. If those times are not very good, we can try to schedule an appointment. Notes from Prof Anderson: “Since I am only in Geneseo on Tuesday and Thursday, those are the best days to schedule an appointment with me if you are unable to make my office hours. If you need to contact me on another day of the week, you may talk to me on the telephone if you like. (See telephoning). Please check the proper phone number at the beginning of this syllabus.” Notes from Prof Drake: “Since I am not in Geneseo until the evening on Monday, and sometimes not at all on Fridays, I encourage you to talk to me on the telephone if you like. (See telephoning). On Fridays that I am here, my on-campus schedule varies, but I will usually be in the office from 10-11AM. On Fridays that I am not here, I will be available at the Connecticut phone number at the same time. (Check your email for the current week’s details.) If I plan to be somewhere else, I will let you know. I do not mind at all if you call me when I am off campus—in fact, I encourage you to do so.” peeves Prof Drake’s, that is, not necessarily in order of importance, include: not using staples; confusing its and it's (read your writing guidelines thoroughly); the extremely common and utterly baffling misspelling of “definitely” as “definately” (we should require Latin from kindergarten to grad school so that people will know that “definitely” derives from the verb “finio, finire, fini, finitum,” “to finish”); writing “based off of” when the more logical term is “based on”; sitting silent as a frozen mushroom—ever tried to strike up a conversation with one?—and not jumping to answer a general discussion question (show you know lots more than a frozen mushroom, and see speaking); making us see the class as a refrigerator car full of frozen mushrooms; concluding essays with “In conclusion...”; using the phrase “today's society” (an entryway into anachronistic vagaries); trying to define something by using Webster's or any other dictionary, as if the dictionary were the last word on defining rich, complex concepts that you are smart enough to explicate on your own; using those giant-format blue books; forgetting to bring blue books to an exam; walking in late (see all i ever needed to know i learned in kindergarten; but walk in late rather than not walking in at all); having Jake Gyllenhaal up to your dorm lounge for Cheez Whiz and Doritos without inviting Prof Drake. perry reading One important component of this class is the study of history. We will be reading Thucydides in some detail, and we will talk about historical backgrounds of each text that we read. Your reading in Perry is crucial for understanding this context as clearly as possible. On each day that the Perry reading is due, we will have a short quiz with several questions (have a piece of paper ready) just after you write your daily study question. You will receive points for each correct answer; these points will convert into extra credit percentage points (rate: four “Perry points” equal one extra credit percentage point) added to your class participation grade. The important thing to remember, though, is that reading about history will help you to make greater sense of the causes and movements of the story of Western thought and culture and will help you place your primary readings (from the Bible, Dante, etc.) into a meaningful context. plagiarism When you use someone else's words or ideas without acknowledging your debt, you commit plagiarism. So please give credit to other people's words. Furthermore, if you are writing on the same topic as a friend, do not consult about the paper beforehand; you may find yourself guilty of a type of plagiarism (seriously; Prof Drake has already seen students do this during my career). A plagiarism conviction can mean a zero on your paper. For more complete information, consult the current college catalogue under “Academic Dishonesty.” printer quality We actually do not care if your papers have a few typos or pen-and-ink corrections as long as everything is nice, dark, and legible. If you can possibly swing it, please use a letter-quality or laser printer—or even a good typewriter. reading In recent studies, most American university students report spending less than half the minimum recommended amount of time studying for classes. The recommended rule of thumb is a minimum of 2-3 hours for each semester hour of classes on one’s schedule. For example, a person taking fifteen semester hours should plan on 30-45 hours per week of reading, re-reading, note-taking, studying, review, and research—depending on the difficulty of the course and your own learning style. You may need to devote even more time when papers are due or exams are coming up. As part of your study plan, please keep up with reading assignments. Class discussion (not to mention your class participation grade) depends on such diligence. This is also the only way to succeed on Perry quizzes. You are responsible for reading and having a basic familiarity with the material regardless of whether we discuss all of it in class. Keep this in mind as you prepare for quizzes and for the midterm. For texts that we do not actually discuss in class, we may assign test questions that a first-time reader of those texts can reasonably answer. You may find this kind of reading takes more time than what you are used to (especially philosophical texts). Some suggestions: don't wait until the night before class to finish reading. Start a week before if you can; make good use of the weekend; parcel out your reading evenly over a period of days to make it more manageable. Become familiar with your books, and try to estimate the level of difficulty of the reading; twenty pages of Plato are not the same thing as twenty pages of Euripides. Try to find places mentioned in the text on maps in your book or in Perry. Use the index. Look up any word you don't know in the dictionary. Draw diagrams of the text's story or argument. Look for answers to the study questions; keep a running list of questions you would ask if the author were there right in front of you; keep notes in a notebook or in the margin of your text; talk to your roommate about fortune and the one true good over month-old peanut butter crackers from the snack machine at 2AM. Consider making your goal that of the main character in Rebecca Lee's short story, “The Banks of the Vistula”: Almost miraculously I had crossed that invisible line beyond which people turn into actual readers, when they start to hear the voice of the writer as clearly as in a conversation. Can you do this in an age of televised soundbytes, of super-short magazine articles, and worm-brain attention spans? Can you take the challenge to listen to the voice of another age, another people, another way of looking at the world—one that might not even seem relevant to you? Can you move beyond your own circumstances, your own use of language, your own expectations of life, humanity, and the universe? We bet you can. No one else will do this for you; only you can do it. And we bet you can. slashed grades Like many professors, we sometimes prefer to give “in-between” grades; for example, B-/C+ means the paper was perhaps mostly of C+ quality, but contains some extra merit that we want to recognize. Obviously, we do not assign slashed semester grades; see hovering. speaking You may have the easiest time in the world chatting with friends, your aunt, the supermarket stock clerk, your boyfriend’s hamster, etc. Speaking in class can be more difficult. You know you are on the spot; an electrifying silence emanates from your classmates as they all take in hungrily what you have to say, as they process and evaluate your remarks, and as we do the same. Yes, there is a lot at stake when you speak up; but it is very important to do so. First of all, your arguments and opinions are very valuable; so do not let just a few actors command the stage, as happens in many classes. Second, the momentum of this class thrives on variety. If we were to stand up front and read you a semester’s worth of notes, without asking you to respond or question or challenge what our texts give us, we might as well just videotape a bunch of lectures and go off to Red Jacket for an endless series of mediocre pizzas. All our voices provide the dialogue (or multilogue) that keeps us all eager and alive. Third, learning to speak up is as important a skill as writing—and in a world where written communication competes fiercely with oral, you need to practice both. Both skills will aid you as a student, an employee, a citizen, a group member, and a friend. Don’t be afraid to say something stupid. If you got into Geneseo in the first place, you already have enough skills to avoid embarrassment. But it happens sometimes. If it does, pick yourself up and move on with dignity. Accept criticism as helpful guidance. You need not worry about losing face with us— we would much rather that you try to articulate thoughts out loud than remain frozen all through the class, and we will not penalize you if you say something flawed. (If you hardly ever say anything, do not expect to get much more than a D for class participation.) Be humorous and cheerful, sarcastic if you must. But avoid cultivating flippancy. Think about other people’s points of view, and respect other persons as persons, even if you have to show that their arguments are dead wrong. Think about what the texts are really saying, too. Reading your assignments on time, reviewing what you have read, and reflecting on the study questions will make it that much easier to speak in class and to get more out of the discussion. A tip for analyzing a work of literature (and really, most of our texts) in class: start by figuring out the literal details. What does the text actually say? What images, events, characters, or abstract concepts appear, and in what sequence? Do this to establish a concrete background before moving on to interpret—to explicate the meaning of a passage. In general, prefer specific, concrete evidence to vague generalities. study questions Before each class, Prof Drake will send you several questions via email. Consider these as you read your assignment. Then, at the beginning of each class, you will spend a few minutes writing a response to (one of) the question(s) for that class in your handy study question booklet. You may be called on to discuss your answer at any time during the class. Use these questions to help prepare for each exam. study question booklet Take two regular-sized blue books and staple them together to form one little notebook. You’ll use one page to answer each study question. Have your study question booklet ready for class starting on 29 January, and bring it to every class, even if we are having an exam or video. We will probably collect these booklets once or twice during the semester, and certainly at the final exam. telephoning We would like you to have access to us when we are off campus. If you have an urgent question or concern that isn’t adequate for email, please phone us at the following times Prof Anderson: up to 10PM on MTWRF. It would be best to schedule a time to phone him on these days; however, if something critical arises, you may phone him, leave a message, and he will return your call as soon as he can. Prof Drake: up to 10PM MTW; till 11PM RFSSu. On Monday through Wednesday evenings, you can leave a message for Prof Drake on his voice mail at the office; on other nights and most holidays, you'll find him in Connecticut. trivia and truth Prof Drake used to say that he was not so much concerned about whether people remembered exactly what year the Emperor Hadrian died or how many times the word “fortune” appears in the works of Christine de Pizan. We still say that, but with this qualification: a crucial part of any academic degree involves mastering basic material in the beginning courses to have a working knowledge of major issues and ideas. This knowledge will assist you in more complex upper-level courses in the future. So you will need to spend time learning names and dates—above all, the dates in the chronology boxes in Perry, centuries of major events and persons, and any dates we put on the board—as well as the major ideas in the texts we are reading. Immersing yourself in both primary and secondary material—including Perry and the introductions to your books (the latter we will not require you to read, but you will find them useful if you do) will help you to engage in a higher-order activity: using the most specific and concrete evidence that you can to support an argument or to flesh out a reading of a text. In any event, improving your critical skills and interpretive sophistication is just as important in this class. Your ultimate goal should be to read and understand arguments and ideas—and ultimately to find them useful in some way for understanding the world. turnover time Normally, we return a set of papers within 10-11 days after their due date. videos At times we will see videos on ancient civilization and the history of art. We will discuss these briefly or refer to them as we talk about our major texts. Please treat these videos as seriously as, say, Perry’s Brief History, i.e., as supplementary texts that put our readings in context and that you will need to know for exams. Use these resources actively, not passively; the more evidence you can show that you are integrating primary text with context, you will not only have the chance to improve your semester grade; you will learn multidimensionally. writing guide and writing guidelines Read this helpful writing advice on the Geneseo website. The direct address is http://writingguide.geneseo.edu/. Study these guidelines and put them into practice to help you construct a good paper. In particular, see the page entitled “Conventions on Writing Papers in the Humanities.” Since you will be writing a significant amount for this class, you should also read through Prof Drake’s set of basic writing guidelines at https://wiki.geneseo.edu:8443/display/writing/English. Please follow these, and please ask me if you have any questions about them. writing learning center The WLC is a peer-tutoring program staffed by English majors. If you're having trouble with narrowing your thesis, organizing your material, or just getting started, go see the tutors on the main floor of Milne Library. The Center is open for appointments on weekdays and on certain weekend hours; you can make an appointment at http://go.geneseo.edu/wlcform . (The WLC will also take walk-in clients if no appointments are expected.) Find out more about the tutors and how they can help you achieve better writing at http://www.geneseo.edu/english/writing_center. CLASS SCHEDULE AND READING ASSIGNMENTS Important Note: Reading assignments [in italics] are indicated on the date by which you should have them read. (Editor’s introductions are optional, but they may provide helpful background information.) We will most likely discuss these readings on that day, but occasionally we will allow for a little flexibility in the schedule. 20 January Introduction SIGN UP FOR DISCUSSION QUESTION BY 6PM ON WEDNESDAY, 21 JANUARY 22 January 27 January 29 January 3 February 5 February 10 February 12 February Introduction to ancient Greece; VIDEO ON GREEK ART; Perry,“Geography of Europe,” xvii and ff; Chapters 1 and 3 VIDEO ON GREEK ART AND CULTURE; Thucydides; Peloponnesian War, 35-49, 72-87; Thucydides; Peloponnesian War, 143-56, 212-23; 236-45; START BRINGING STUDY QUESTION BOOKLET TO CLASS Thucydides, 400-08, 414-29; Euripides; Medea (all); TOPICS FOR FIRST ESSAY HANDED OUT IN CLASS Plato; Republic, Book I (note: read all of the summaries to the books of The Republic, including books that we do not read for class) Plato; Republic, Books III, IV, and VI Plato; Republic, Books VII-VIII; Aristotle (lecture, with home appliances) FIRST ESSAY DUE ON MONDAY, 16 FEBRUARY BY 11AM AT THE ENGLISH DEPARTMENT OFFICE (WELLES 226) 17 February 19 February 24 February 26 February 3 March 5 March 10 March 12 March The Bible; Hebrew Scriptures: Genesis (all); Exodus (read all); Perry, Chapter 2 The Bible; Hebrew Scriptures: Exodus (finish discussion); Psalms; Amos The Bible; Christian Scriptures: Luke; Perry, Chapter 5 The Bible; Christian Scriptures: Acts; Romans Virgil; Aeneid, Books I and II; Perry, Chapter 4 Virgil; Aeneid, Books III, IV, and VI Virgil; Aeneid, Book 12; VIDEO ON ROMAN ART; discussion MIDTERM EXAM; you may arrive at 7.30AM if you wish; bring two blue books s 24 March 26 March 31 March 2 April p r i n g b r e a k Augustine; Confessions, Books I-IV; TOPICS FOR SECOND ESSAY HANDED OUT IN CLASS Augustine; Confessions, Books V-VIII Augustine; Confessions, Book IX; Boethius; Consolation of Philosophy, Book I; Perry, Chapter 6; (MAUNDY THURSDAY) Boethius; Introduction to Islam; Consolation of Philosophy, Books II-V; myCourses readings on Islam SECOND ESSAY DUE ON MONDAY, 6 APRIL BY 11AM IN THE ENGLISH DEPARTMENT OFFICE 7 April 9 April 14 April 16 April 21 April 23 April 28 April 30 April 5 May VIDEO ON MEDIEVAL ART; Introduction to Islam (cont’d); introduction to Dante; Inferno, Cantos 1-10; Perry, Chapter 7 Dante; Inferno, Cantos 11-20 Dante; Inferno, Cantos 21-27 Dante (cont’d.), Cantos 28-34; Christine de Pizan; Book of the City of Ladies, 116-55 G.R.E.A.T. DAY; no class today; please attend G.R.E.A.T. Day sessions Christine de Pizan; The Path of Long Study, 59-87 Shakespeare; Hamlet, Acts I and II; Perry, Chapter 8 Shakespeare; Hamlet, Acts III-V; conclusion; FINAL EXAM (PART I) TAKE-HOME ESSAY TOPICS HANDED OUT AT THE END OF CLASS VIDEO ON EARLY RENAISSANCE ART; discussion; FINAL EXAM (PART I) DUE IN CLASS FINAL EXAM (PART II) IN CLASS ON FRIDAY, 8 MAY, 8-11AM On a final note…why learn about all of this? BECAUSE acquiring this knowledge is difficult. Because you will feel triumphant when it no longer confuses you. Because you will enjoy what you can do with it. Because in learning it you may discover new perspectives on life, new ways of thinking. Because its possession will make you more alive than its alternative, which is ignorance. J. M. Banner and H.C. Cannon