overarching themes - NYU School of Law

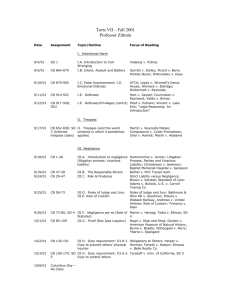

advertisement