20121218-183646

advertisement

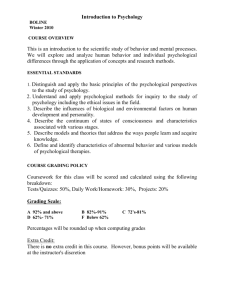

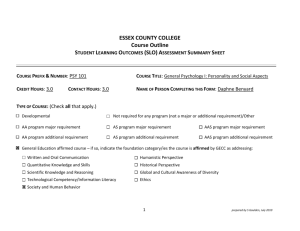

METHODOLOGICAL INSTRUCTION for the lesson Theme : Subject, objectives and methods of psychological study of the human condition. Definition of mental health. For 4-th year students of medical faculty 1. Actuality Aim Medical psychology includes the scientific study and application of psychology for the purpose of understanding, preventing, and relieving psychologically-based distress or dysfunction and to promote subjective well-being and personal development. Central to its practice are psychological assessment and psychotherapy, although clinical psychologists also engage in research, teaching, consultation, forensic testimony, and program development and administration. 2. Hours: 2 3. Teaching goal The students must know: - the subject and objectives of medical psychology; - the history of world and national medical psychology, current state of Ukrainian medical psychological service and the outlook for its development; - physiological mechanisms of consciousness, materialist understanding of psychic processes; - research methods of psychological processes and personality. and be able to: - objectively and scientifically determine the place and role of medical psychology among other clinical disciplines; - interpret conditions to create healthy psychological climate in the medical environment; - analyze psychological peculiarities of patients with various pathologies; - to determine the way of communication with patients with accentuated personality; - know methods of research in medical psychology; - evaluate the results of experimental-psychological research of particular psychological processes and patient’s personality. Assimilate practical skills - analyze psychological peculiarities of patients with various pathologies; - communication with patients; - methods of research in medical psychology; - experimental-psychological research of particular psychological processes and patient’s personality. 4. List of disciplines necessary for learning theme 1 Title of the discipline Anatomy General psychology Neuropsychology Normal physiology Content of the discipline necessary for learning medical psychology Brain construction Psychic functions of a normal person. Consciousness and self-consciousness. Psychology of personality. Functions of different brain structures. Brain functions. Physiology of high nervous activity. 5. Content of the theme Clinical psychology includes the scientific study and application of psychology for the purpose of understanding, preventing, and relieving psychologically-based distress or dysfunction and to promote subjective well-being and personal development. Central to its practice are psychological assessment and psychotherapy, although clinical psychologists also engage in research, teaching, consultation, forensic testimony, and program development and administration. The field is often considered to have begun in 1896 with the opening of the first psychological clinic at the University of Pennsylvania by Lightner Witmer. In the first half of the 20th century, clinical psychology was focused on psychological assessment, with little attention given to treatment. This changed after the 1940s when World War II resulted in the need for a large increase in the number of trained clinicians. Since that time, two main educational models have developed—the PhD (focusing on research) and the PsyD (focusing on practice). Clinical psychologists are now considered experts in providing psychotherapy, and generally train within four primary theoretical orientations—Psychodynamic, Humanistic, Cognitive Behavioral, and Systems or Family therapy. Clinical psychology can be confused with psychiatry, which generally has similar goals (e.g. the alleviation of mental distress) with a similar client group, but is unique in that psychiatrists are medical practitioners, licensed to prescribe medication as the primary treatment modality. Although modern, scientific psychology is often dated at the 1879 opening of the first psychological laboratory by Wilhelm Wundt, attempts to create methods for assessing and treating mental distress existed long before. The earliest recorded approaches were a combination of religious, magical and medical perspectives. In the early 1800s, one could have his or her head examined, literally, using phrenology, the study of personality by the shape of the skull. Other popular treatments included physiognomy—the study of the shape of the face—and mesmerism, Mesmer's treatment by the use of magnets. Spiritualism and Phineas Quimby’s "mental healing" were also popular. While the scientific community eventually came to reject all of these methods, academic psychologists also were not concerned with serious forms of mental illness. That area was already being addressed by the developing fields of psychiatry and neurology within the asylum movement. It wasn't until the end of the 19th century, around the time when Sigmund Freud was first developing his "talking cure” in Vienna, that the first scientifically clinical application of psychology began. By the second half of the 1800s, the scientific study of psychology was becoming well established in university laboratories. Although there were a few scattered voices calling for an applied psychology, the general field looked down upon this idea and insisted on "pure" science as the only respectable practice. This changed when Lightner Witmer (1867-1956), a past student of Wundt and head of the psychology department at the University of Pennsylvania, agreed to treat a young boy who had trouble with spelling. His successful treatment was soon to lead to Witmer's opening of the first psychological clinic at Penn in 1896, dedicated to helping children with learning disabilities. Ten years later in 1907, Witmer was to found the first journal of this new field, The Psychological Clinic, where he coined the term "clinical psychology," defined as "the study of individuals, by observation or experimentation, with the intention of promoting change." The field began to organize under the name "clinical psychology" in 1917 with the founding of the American Association of Clinical Psychology. This only lasted until 1919, after which the American Psychological Association (founded by G. Stanley Hall in 1892) developed a section on Clinical Psychology, which offered certification until 1927. Growth in the field was slow for the next few years when various unconnected psychological organizations came together as the American Association of Applied Psychology in 1930, which would act as the primary forum for psychologists until after World War II when the APA reorganized. In 1945 APA created what is now called Division 12, its division of clinical psychology, which remains a leading organization in the field. Psychological societies and associations in other English-speaking countries developed similar divisions, including in Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. When World War II broke out, the military once again called upon clinical psychologists for their assessment expertise. As soldiers began to return from combat, psychologists started to notice symptoms of psychological trauma labeled "shell shock" (eventually to be termed Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder that were best treated as soon as possible. Because physicians (including psychiatrists) were overextended in treating bodily injuries, psychologists were called to help treat this condition. At the same time, female psychologists (who were excluded from the war effort) formed the National Council of Women Psychologists with the purpose of helping communities deal with the stresses of war and giving young mothers advice on child rearing. WWII helped bring dramatic changes to clinical psychology, not just in America but internationally as well. Graduate education in psychology began adding psychotherapy to the science and research focus based on the 1947 scientistpractitioner model, known today as the Boulder Model, for PhD programs in clinical psychology. Clinical psychology in Britain developed much like in the U.S. after WWII, specifically within the context of the National Health Service with qualifications, standards, and salaries managed by the British Psychological Society. Clinical psychologists can offer a range of professional services, including: Provide psychological treatment (psychotherapy) Administer and interpret psychological assessment and testing Conduct psychological research Teach Development of prevention and treatment programs Consultation (especially with schools and businesses) Program administration Provide expert testimony (forensic psychology) In practice, clinical psychologists may work with individuals, couples, families, or groups in a variety of settings, including private practices, hospitals, mental health organizations, and non-profit agencies. Most clinical psychologists who engage in research and teaching do so within a college or university setting. Clinical psychologists may also choose to specialize in a particular field—common areas of specialization, include: Specific disorders (e.g. trauma, addiction, eating, sleep, sex, depression, anxiety, or phobias) Neuropsychological disorders Child and adolescent Family and relationship counseling Health Sport Forensic The field of clinical psychology in most countries is strongly regulated by a code of ethics. The Code generally sets a higher standard than that which is required by law as it is designed to guide responsible behavior, the protection of clients, and the improvement of individuals, organizations, and society. The Code is applicable to all psychologists in both research and applied fields. The Code is based on five principles: Beneficence and Nonmaleficence, Fidelity and Responsibility, Integrity, Justice, and Respect for People's Rights and Dignity. Detailed elements address how to resolve ethical issues, competence, human relations, privacy and confidentiality, advertising, record keeping, fees, training, research, publication, assessment, and therapy. An important area of expertise for many clinical psychologists is psychological assessment, and there are indications that as many as 91% of psychologists engage in this core clinical practice. Such evaluation is usually done in service to gaining insight into and forming hypotheses about psychological or behavioral problems. As such, the results of such assessments are usually used to create generalized impressions (rather than diagnoses) in service to informing treatment planning. Methods include formal testing measures, interviews, reviewing past records, clinical observation, and physical examination. A basic method of research is clinical method. It include clinical interview and observation (Pose (natural – unnatural; symmetric – asymmetric, closed – opened). Gestures: communicative and expressive. Mimicry is the co-coordinated motions of muscles persons, which represent emotions, mood, sense). After that we use experimental-psychological research, which include tests, questionnaires. Tests – the methods of purposeful, specialized, identical for all explored psychological diagnostic research, which is conducted in the severely controlled terms and at application of which it is possible to get exact quantitative and highquality description of the phenomenon which is studied. There exist literally hundreds of various assessment tools, although only a few have been shown to have both high validity (i.e., test actually measures what it claims to measure) and reliability (i.e., consistency). These measures generally fall within one of several categories, including the following: Intelligence & achievement tests. These tests are designed to measure certain specific kinds of cognitive functioning (often referred to as IQ) in comparison to a norming-group. These tests, such as the WISC-IV, attempt to measure such traits as general knowledge, verbal skill, memory, attention span, logical reasoning, and visual/spacial perception. Several tests have been shown to predict accurately certain kinds of performance, especially scholastic. Personality tests. Tests of personality aim to describe patterns of behavior, thoughts, and feelings. They generally fall within two categories: objective and projective. Objective measures, such as the MMPI, are based on restricted answers—such as yes/no, true/false, or a rating scale—which allow for computation of scores that can be compared to a normative group. Projective tests, such as the Rorschach inkblot test, allow for open-ended answers, often based on ambiguous stimuli, presumably revealing non-conscious psychological dynamics. Neuropsychological tests. Neuropsychological tests consist of specifically designed tasks used to measure psychological functions known to be linked to a particular brain structure or pathway. They are typically used to assess impairment after an injury or illness known to affect neurocognitive functioning, or when used in research, to contrast neuropsychological abilities across experimental groups. Clinical observation. Clinical psychologists are also trained to gather data by observing behavior. The clinical interview is a vital part of assessment, even when using other formalized tools, which can employ either a structured or unstructured format. Such assessment looks at certain areas, such as general appearance and behavior, mood and affect, perception, comprehension, orientation, insight, memory, and content of communication. One common example of a formal interview is the mental status examination, which is often used as a screening tool for treatment or further testing The TAT is popularly known as the picture interpretation technique because it uses a standard series of 30 provocative yet ambiguous pictures about which the subject must tell a story. In the case of adults and adolescents of average intelligence, a subject is asked to tell as dramatic a story as they can for each picture, including: what has led up to the event shown what is happening at the moment what the characters are feeling and thinking, and what the outcome of the story was. 5.2. Theoretical questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. What does medical psychology study? Methods of psychological assessment of man? Describe historical periods of the development of medical psychology. Tasks of medical psychology. What is the basic method of research on medical psychology? What tests do you know? Describe personality tests. Clinical observation. 5.3. Practical training during the tutorial 1. Clinical observation of the behavior of the patient. 2. Clinical interview and plan of psychological research. 5.4. Materials for self-control A. Questions for self-control: 1) What does medical psychology study? 2) Methods of psychological assessment of man? 3) Describe historical periods of the development of medical psychology. 4) Tasks of medical psychology. 5) What is the basic method of research on medical psychology? 6) What tests do you know? 7) Describe personality tests. 8) Clinical observation. B. Tasks for self-control 1. Typical, ordinary – II level. 2. Untypical, no ordinary – III level. C. Tests for self-control. Literature 1. R.J.Gatchel An introduction to health psychology. – New York: Random house. – 386 p. 2. Lectures. 3. Internet resource. 4. Вітенко І.С., Вітенко Т.І. Основи психології: Підручник для студентів вищих медичних навчальних закладів ІІІ – ІV рівнів акредитації. – Вінниця, 2001. 5. Вітенко І.С., Чабан О.С., Бусло О.О. Сімейна медицина: психологічні аспекти діагностики, профілактики і лікування хворих. – Тернопіль, ”Укрмедкнига”, 2002. 6. Гавенко В.Л., Вітенко І.С., Самардакова Г.О. Практикум з медичної психології. – Харків: Регіон-інформ, 2002. 7. Загальна та медична психологія (практикум) /Під заг. ред. професора І.Д.Спіріної, професора І.С.Вітенка. – Дніпропетровськ, АРТ ПРЕС, 2002. 8. Квасенко А.В., Зубарев Ю.Т. Психология больного. М., 1980. 9. Лакосина Н.Д., Ушаков Г.К. Медицинская психология. М., 1984. 10.Менделевич В.Д. Клиническая и медицинская психология. – М.: Мед.прес., 1998. 11.Мягков И.Ф., Боков С.Н. Медицинская психология: основы патопсихологии и психопатологии: Учебник для вузов.- М.: Издательская корпорация „Логос”, 1999. Prepared by assistant V.A. Herasymuk