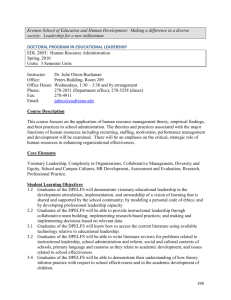

Decision Making

advertisement

Decision Making Module 3 LIS 580: Spring, 2006 Instructor- Michael Crandall Roadmap • • • • • Types of decisions Models of decision making The decision making process Creativity Shortcuts and traps April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 2 Connecting the Dots • “Making warning systems more sensitive reduces the risk of surprise, but increases the number of false alarms, which in turn reduces sensitivity” • “The Chief of Staff has to make decisions, and his decisions must be clear… To be sure, the clearer and sharper the estimate, the clearer and sharper the mistake..” April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 3 Understanding Decision Making • Puzzles, Problems, and Wicked Problems – A discrepancy between a desirable and an actual situation. – Well structured, ill-structured, and complex problems. • Decision – A choice made between available alternatives. • Decision Making – The process of developing and analyzing alternatives and choosing from among them. • Judgment – The cognitive, or “thinking,” aspects of the decision-making process. G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 4 Wicked Problems • • • • • • • • • • • • Proposed by H.J. Rittel and M. Webber of UC Berkeley in 1973. Wicked problems do not have an exhaustive set of potential solutions. Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem. Discrepancies in representing a wicked problem can be explained in numerous ways--the choice of explanation in turn determines the nature of the problem's resolution. Every wicked problem is essentially unique--lessons-learned are hard to transfer across to other problems. Wicked problems are often "solved" through group efforts. Wicked problems require inventive/creative solutions. Every implemented solution to a wicked problem has consequences, and may cause additional problems. Wicked problems have no stopping rule(s). Solutions to wicked problems are not true-or-false, but instead better, worse, or good enough. There is no immediate and no ultimate test of a solution to a wicked problem. The planner or designer (solving the problem) has no inherent right to solve the problem, and no permission to make mistakes. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wicked_problems April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 5 Types of Decisions Ill-structured Type of Problem Well-structured Nonprogrammed Decisions Programmed Decisions Top Level in Organization Bottom • Programmed Decision – A decision that is repetitive and routine and can be made by using a definite, systematic procedure. • Nonprogrammed Decision – A decision that is unique and novel. • The Principle of Exception – “Only bring exceptions to the way things should be to the manager’s attention. Handle routine matters yourself.” G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 6 Procedure and Form to Use for Developing a Workplace Rule FIGURE 3–1 Source: Copyright Gary Dessler, Ph.D. April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 7 Decision-Making Models • The Classical Approach – Have complete or “perfect” information about the situation. – Distinguish perfectly between the problem and its symptoms. – Identify all criteria and accurately weigh all the criteria according to preferences. – Know all alternatives and can assess each one against each criterion. – Accurately calculate and choose the alternative with the highest perceived value. – Make an “optimal” choice without being confused by “irrational” thought processes. The problem is clear and unambiguous A single, welldefined goal is to be achieved All alternatives and consequences are known Preferences are clear Preferences are constant and stable No time or cost constraints exist Final choice will maximize economic payoff G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 8 Decision-Making Models (cont’d) • The Administrative Approach – Bounded Rationality (Herbert Simon) • The boundaries on rational decision making imposed by one’s values, abilities, and limited capacity for processing information. – Satisfice • To stop the decision-making process when satisfactory alternatives are found, rather than to review solutions until an optimal alternative is discovered. G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 9 Checklist 3.1 The Decision-Making Process Define the problem. Clarify your objectives. Identify alternatives. Analyze the consequences. Make a choice. G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 10 Step 1. Define the Problem 1. Start by writing down your initial assessment of the problem. 2. Dissect the problem. – What triggered this problem (as I’ve assessed it)? – Why am I even thinking about solving this problem? – What is the connection between the trigger and the problem? G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 11 Step 2. Clarify Your Objectives 1. Write down all the concerns you hope to address through your decision. 2. Convert your concerns into specific, concrete objectives. 3. Separate ends from means to establish your fundamental objectives. 4. Clarify what you mean by each objective. 5. Test your objectives to see if they capture your interests. G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 12 Step 3. Identify Alternatives 1. Generate as many alternatives as you can yourself. 2. Expand your search, by checking with other people, including experts. 3. Look at each of your objectives and ask, “how?” 4. Know when to stop. G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 13 Step 4. Analyze the Consequences 1. Mentally put yourself into the future. – Process Analysis • Solving problems by thinking through the process involved from beginning to end, imagining, at each step, what actually would happen. 2. Eliminate any clearly inferior alternatives. 3. Organize your remaining alternatives into a table (matrix) that provides a concise, bird's-eye view of the consequences of pursuing each alternative. G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 14 Consequence Matrix G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 15 Step 5. Make a Choice • Analyses are useless unless the right choice is made. – Under perfect conditions, simply review the consequences of each alternative, and choose the alternative that maximizes benefits. – In practice, making a decision—even a relatively simple one like choosing a computer—usually can’t be done so accurately or rationally. G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 16 How To Make Better Decisions 1. Increase Your Knowledge – – – – – Ask questions. Get experience. Use consultants. Do your research. Force yourself to recognize the facts when you see them (maintain your objectivity). 2. Use Your Intuition – A cognitive process whereby a person instinctively makes a decision based on his or her accumulated knowledge and experience. G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 17 Are You More Rational or More Intuitive? Source: Adapted and reproduced by permission of the Publisher, Psychological Assessment Resources. Inc., Odessa FL 33556, from the Personal Style Inventory by William Taggart, Ph.D., and Barbara Hausladen. Copyright 1991, 1993 by PAR, Inc. April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 FIGURE 3–2 G.Dessler, 2003 18 How To Make Better Decisions (cont’d) 3. Weigh the Pros and Cons – Quantify realities by sizing up your options, and taking into consideration the relative importance of each of your objectives. 4. Don’t Overstress the Finality of Your Decision – Remember that few decisions are forever. – Knowing when to quit is sometimes the smartest thing a manager can do. 5. Make Sure the Timing Is Right G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 19 Decision Matrix • Use weights to provide adjustments for importance of criteria • Often subjective, but helps to prioritize FIGURE 3–3 G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 20 Creativity and Decision Making • Creativity – The process of developing original, novel responses to a problem. Creativity skills Expertise • Brainstorming Creativity – A creativity-stimulating technique in which prior judgments and criticisms are specifically forbidden from being expressed in order to encourage the free flow of ideas which are encouraged. Task motivation • Nominal group technique – A decision-making technique in which group members are physically present but operate independently G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 21 Nominal Group Technique • Each participant contributes individual ideas • Ideas are then ranked individually • Totals are summed for final rank http://www.ryerson.ca/~mjoppe/ResearchProcess/841TheNominalGroupTechnique.htm April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 22 Checklist 3.4 How to be More Creative Create a culture of creativity. Encourage brainstorming. Suspend judgment. Get more points of view. Provide physical support for creativity. Encourage anonymous input. G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 23 Decision-making Shortcuts and Traps • Using a Heuristic – Applying a rule of thumb or an approximation as a shortcut to decision making. • Anchoring – Unconsciously giving disproportionate weight to the first information available. • Adopting a Psychological Set – The tendency to rely on a rigid strategy or approach when solving a problem. • Perception (Personal Bias) – The unique way each person defines stimuli, depending on the influence of past experiences and the person’s present needs and personality. G.Dessler, 2003 April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 24 Using Creativity to Find a Solution Source: Applied Human Relations, 4th ed., by Benton/Halloran cW 1991. Reprinted by permission of Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 FIGURE 3–6 G.Dessler, 2003 25 Next Time • We’ll talk about planning basics • Read Chapter 4 and assigned articles • For discussion article, think about these questions: – Do you think EMP used a well-defined planning process prior to opening? – Since the opening? – If any planning has been done, who do you think has been involved in it? – Does planning matter in this situation? – What steps might EMP take to provide more success in the future? April 4, 2006 LIS580- Spring 2006 26