Rural and Northern Community Response to Intimate Partner Violence

Jasper National Park Lake Moraine in Banff National Park

RURAL AND NORTHERN COMMUNITY

RESPONSE TO INTIMATE PARTNER

VIOLENCE IN CANADA

ACTION RESEARCH PROJECT

The Rural and Northern Community Response to Intimate Partner

Violence (IPV) is an action research project that is enhancing the understanding of effective community response to IPV in rural and northern regions of the Canadian prairie provinces and the

North West Territories (NWT) and will lead to policy change through actions of our community partners.

ACADEMIC & COMMUNITY PARTNERS

This project is led by PI, Dr. Mary Hampton with the Research and

Education for Solutions to Violence and Abuse (RESOLVE) office based in Saskatchewan at the University of Regina, and academic partners from eight universities with expertise conducting community-based anti-violence research.

The teams are working with partners from two community sectors

(shelter and victim services providers, and the justice system) in each province and territory.

TEAM GRANT

Eighteen academic researchers and 15 community partners comprise the CURA research team.

The project brings together researchers from universities in each of the three Prairie provinces and NWT and co-applicants, collaborators and partners including governmental justice, social services, and shelters.

ALBERTA RESEARCH TEAM

- Sylvia Barton (Co-I, Academic Lead, University of Alberta)

- Brenda Brochu (Co-I, Community Lead, Peace River)

- Dawn McBride (Co-I, University of Lethbridge)

- Nicole Letourneau (Co-I, University of Calgary

- Sharon Mailloux (Community Partner, Peace River)

- Krista Hungler (Program Research Coordinator)

COMMUNITY UNIVERSITY RESEARCH ALLIANCE

PROJECT

Project Goals & Objectives

Relevance of the Research

Literature Review

Methodology

GIS Maps

Conclusion

PROJECT GOALS & OBJECTIVES

CURA PROJECT

This Community University Research Alliance (CURA) project is providing information to academics, as well as family violence service providers and justice system policy makers that will facilitate support in targeted areas experiencing IPV.

In light of the over 38,000 incidents of family violence reported by

Statistics Canada in 2006 (Ogrodnik, 2008), we consider this to be a timely and necessary project.

SOCIETAL COSTS

There are many costs to IPV, not only to women, but to their children as well (Taylor-Butts, 2004; Tutty & Rothery, 2002).

There are further substantial costs to society such as charging abusive partners and providing treatment in the hope of stopping violent behaviour (Ursel, 2002; Ursel, Tutty & LeMaistre, 2009).

GOALS

To enhance our understanding of effective community response to IPV in rural and northern regions of the Canadian Prairie

Provinces and North West Territories (NWT).

To provide information to academics as well as family violence service providers and justice system policy makers that will facilitate support in targeted areas experiencing IPV.

OBJECTIVES

To integrate several sources of data to create an action plan that maps the socio-spatial problem of IPV.

To create narratives describing community response in rural and northern areas of the prairie provinces and NWT.

To generate a grounded theory as a practical tool to create and sustain non-violent communities in these regions of Canada.

RELEVANCE OF THE RESEARCH

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as a range of physically, sexually, and psychologically coercive and controlling acts used against an adult woman by a current or former male or female intimate partner (Ellsberg & Heise, 2005).

FEMINIST LENS

We focus on violence against women for practical reasons, as the majority of previous research focuses on women as survivors, allowing for comparison.

Furthermore, as women experience more severe injury due to IPV, using a feminist lens allows for the deconstruction of existing power relations based on gender dynamics (Statistics Canada,

2006; Walker & Shapiro, 2003).

PREVALENCE & GAPS

The prevalence of IPV in Canada ranges from 3% to 56% (Coker, et al., 2000; Seager, 2009).

Despite sustained research into IPV, numerous gaps have been identified, including the need for research conducted within a

Canadian context, the unique experiences of specific populations of women (e.g., Aboriginal Canadians), and the experience of women in rural and northern communities.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Studies indicate that women living in isolated communities are often at greater risk of violence and have fewer resources available to them (McCallum & Lauzon, 2005); Romans, et al.,

2007).

INADEQUATE IPV RESPONSE

Existing research describing criminal justice response and services to victims of violent crimes do not adequately address the specific issue of IPV or the unique needs of rural and northern communities in Canada (Levan, 2003; Hughes, 2010; Wemmers

& Canuto, 2002).

RESEARCH FOCUS

Women Living in Rural Communities of the Prairie Provinces

Northern Canada

Aboriginal Women Living in Rural and Northern Areas of the

Prairie Provinces

PRAIRIE PROVINCES & NWT

IPV is a serious social problem in the Prairie Provinces and NWT; these regions report the highest rates of shelter utilization to escape sexual abuse, highest rates of sexual assault, and highest rates of IPV in the country (Brennan & Taylor-Butts, 2008;

Statistics Canada, 2006, 2009; 2007/2008).

Saskatchewan currently reports the highest rates of spousal homicide and sexual assault in Canada (Brennan & Ta;ylor-Butts,

2008; Millhoran, 2005).

MANITOBA , ALBERTA, NWT

Manitoba also reports high rates of assault, emergency calls, and arrests rates related to IPV (Ursel, 2000).

Recent research confirms Alberta’s high rate of spousal violence wherein 10% of women in Alberta were victims of spousal assault, making it the highest rate in the country (the national average was 7%) (GSS, 2004). Alberta has also experienced one of the highest rates of female/IPV homicide rates over the last three decades (Milhoran, 2005).

Although Family Violence statistics are rarely reported by individual territory, statistics suggest that the NWT experiences much higher than average rates of IPV (Kramer, et al., 2004; Paletta,

2008).

ABORIGINAL WOMEN

Aboriginal women are at greater risk of IPV than non-Aboriginal women (21% VS 7%) (Amnesty International, 2004; Brownridge,

2003; Wahab & Olson, 2004).

Aboriginal women also experience barriers to personal empowerment, including the impact of colonization and racism that are linked to higher rates of alcohol and substance abuse, and disruption of family systems due to residential school abuse

(Campbell, 2007; Proulx & Perrault, 2000; Wesley-Esquimaux, &

Smolewski, 2004; Wood & Magen, 2009).

RURAL & NORTHERN

Populations in the prairies have a higher percentage of “rural” and

“northern” communities than other provinces.

In 2001, Statistics Canada classified 20% of the Canadian population as “rural”; however, percentages are higher in the

Prairie Provinces (36% in Saskatchewan; 28% in Manitoba; and

19% in Alberta).

Farming communities are common in these provinces and previous research suggests that IPV among farm women is higher than average (Fletcher, et al., 1996; Kubik, 2005; Kubik & Moore,

2005).

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

What are the unique needs of victims of IPV living in rural and northern regions of the Prairie Provinces and NWT in Canada?

What are the gaps that exist in meeting these needs?

How do we create non-violent communities in these regions?

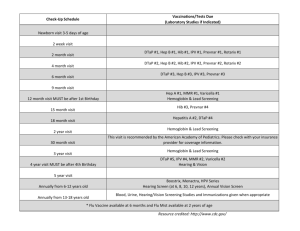

METHODS – YEAR 1

Year 1: Environmental scan, GIS mapping of supports/resources and incidents.

Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping has been used successfully in the past, but is still an innovative method for this topic (Lobao & Murray, 2005; Rambaldi, et al., 2006; Regan, et al., 2007).

METHODS – YEAR 1

a)First source of data: Filled in gaps of an environmental scan completed during a previous research project by adding and updating formal/informal supports.

Data was collected by phoning shelters and services in all rural and northern communities and updating or adding services/ supports.

Mapped by longitude and latitude were all formal IPV supports (i.e., social services in the form of shelters, victim services, treatment programs, and justice system supports/courts that exist in our current environmental scan (Ansara & Hindin, 2010; Lobao &

Murray, 2005; Laws, 1992; Steinberg & Steinberg, 2006).

METHODS – YEAR 1

(b) Second source of data: Information describing IPV incidents

(prevalence) that was accessed as aggregated data in Ottawa and reflective of RCMP detachment activity in targeted areas that reported incidents of IPV from years 1995-2012.

These years were chosen since they include family violence reports provided by Statistics Canada, and we include these urban statistics on our map (Stats Can, 2006).

Travel time and distance from incident to support service are being mapped, as well as changes in resources/supports over time.

METHODOLOGY - YEAR 2

Year 2: Finish GIS mapping, interviewing of front-line service providers in rural and northern provinces and territories.

(a) Mapping of all information variables with location analysis and superimposing of maps are being completed.

(b) Conduction of individual qualitative interviews (30 per region/120 total) with directors of those delivering services in rural and northern regions of the provinces by telephone or in person.

METHODOLOGY – YEAR 3

Year 3: Community selection and completion of in-depth/case study community profiles.

To generate in-depth understanding of community response to IPV, we will generate community profiles of about 14 communities in our provinces/territory, and identify communities for in-depth profiling.

Based on review of the map and analysis of key informant qualitative interviews, two rural/two northern communities in each prairie province, two First Nations in each province, and two communities in the NWT will be identified for in-depth community profiling using case study methodology (Yin, 2008).

Particular attention will be given to communities with relatively high or low incidence of IPV.

METHODOLOGY – YEAR 4

Year 4: Triangulation of all data with modeling creation of nonviolent communities.

Using our GIS maps and qualitative information, we will validate with community experts emerging community narratives and emerging grounded theory describing ways to create non-violent communities, first through our research team meetings and then with target communities.

METHODOLOGY – YEAR 5

Year 5: Knowledge transfer and dissemination.

Creating non-violent communities in rural and northern Canada will involve action steps using results of data collected and analyzed in years 1-4, and conducting a variety of knowledge exchange activities.

An important component of these activities will be organizing community events in each community that was profiled, to share results, raise awareness, and mobilize community action.

Technical support will be hired to create innovative web resources for rural and northern communities to access results and share experiences.

CONTEXT OF MAP 1

Part of the reason to show you solely NWT is because it is all considered

Northern. Also all of the communities are likely to be considered for the project because of their small size (with the exception of Yellowknife).

The mapping data was all obtained from the Government of Canada, through the University of Saskatchewan’s GIS Library. The projection of the map is based on the default setting that came with the Provincial boundaries.

There were several communities that were missing from the data provided by the Government of Canada website (ex. D’Nilo and Dettah) so they were added in manually using Google maps. To determine the missing communities, the listing on Wikipedia of communities in the Northwest

Territories was used.

FOCUS ON SHELTERS

There are 6 shelters in the North West Territories.

The communities in black do not have shelters located in the community.

There are no shelters in NWT that have 2 nd stage housing, so that was not included.

The communities with shelters were determined by the environmental scans and further data on shelters were obtained through personal research and inquiry, but the environmental scans were used to decrease potential errors and also to standardize the information used.

CONTEXT OF MAP 2

This map provides an idea of what areas have services available for incidents of IPV.

As you can see, though there are RCMP detachments in the central part of the Territory, there are no services available for survivors of IPV or emergency shelters for those experiencing IPV to go.

Other things to recognize as we flip from one slide to the other, is the fact that many communities without RCMP detachments likely have IPV incidents that go unreported or under-reported, because of the lack of services available.

FOCUS ON BOTH SERVICES

The communities marked with a black triangle typically stay black, meaning without services. Look at Trout Lake as an example or

Colville Lake.

Also the communities with both services have both for good reason; they are, as evidenced by these maps, the communities with higher incidents of IPV, for example Fort Smith and Inuvik.

CONTEXT OF MAP 4

The rates of IPV in NWT are concerning.

Many of these communities are quite small and the large number of reported incidents are troubling.

It is curious to know how many of these incidents are reported by the same woman.

It is also curious to think about what the rates would be like if more communities had RCMP detachments with full-time employees.

Gameti is the community where a woman was beaten to death, recently.

CONCLUSION

IPV, as with all violence against women, is epidemic, and a global issue that transcends culture, economics, political ideology, and historical time frames.

It can no longer be understood as an issue limited to individual women but must be considered to be a product of social, political, and cultural structures.

By interacting with communities, community researchers and university researchers, this research project will contribute to ending IPV through awareness, and assisting to shape policy and government and community responses to IPV.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Project funding from the Community-University Research

Alliance (CURA), Social Sciences and Humanities

Research Council (SSHRC) is gratefully acknowledged.

Our multidisciplinary team of academics, community partners and Aboriginal advisory group from Alberta,

Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Northwest Territories is deeply appreciated.

Jasper National Park Lake Moraine in Banff National Park