The Basics of Effective Evaluations in the Era of NAS

advertisement

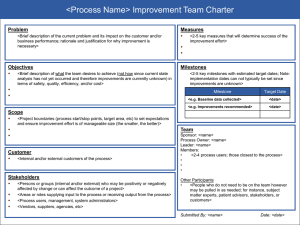

Conflict of Interest Nancy Piro, PhD - No Conflicts of Interest to Declare Ann Dohn, MA - No Conflicts of Interest to Declare PC002 BR04 The Basics of Effective Evaluations in the Era of NAS Nancy Piro, PhD Program Manager & Education Specialist Ann Dohn, MA DIO, Director of GME Graduate Medical Education Workshop Objectives Understand how: – – Evaluation impacts NAS NAS impacts evaluations Design and implement a valid & reliable resident evaluation process. – – – Unintended cognitive bias The impact of self-fulfilling prophesy Evaluation questions What Are Milestones ? Defined areas of competency/expectations – – – We know what we expect of trainee Trainee knows what is expected of them Public knows what a ‘pathologist’, for example, should know and be able to do when certified as … “competent to practice pathology without supervision” Milestones Levels (from Dreyfus) – – – – – Novice PGY-0 Advanced Beginner PGY-1 Competent PGY-2 and 3 Proficient Practitioner PGY-4/5 Expert Practitioner - Ongoing Each trainee assessed with respect to level for each competency Milestones List of competencies to be attained by trainee Some milestones are still in development Milestones are within the ACGME existing 6 core competencies Each milestone is defined as continuum with respect to each level of competency from level 1 to level 5 Rating Scales: Levels 1 to 5 Where do these level 1-5 come from? Dreyfus Model in a Nutshell… “In acquiring a skill by means of instruction and experience, the trainee normally passes through five developmental stages: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Novice Competence Proficiency Expertise Mastery” Dreyfus Model (1980): Characteristics of each stage of developing expertise * Rigid adherence to taught rules or plans * Little situational perception * No discretionary judgment 1 Novice 2 Advanced Beginner * Guidelines for action based on attributes or aspects * Situational perception still limited * All attributes and aspects are treated appropriately and given equal importance 4 Proficient * Coping with 'crowdedness' * Now sees actions at least partly in terms of longer-term goals * Conscious deliberate planning * Standardized and routinized procedures * Sees situations holistically rather than in terms of aspects * See what is most important in a situation * Perceives deviations from the normal patterns * Decision-making less labored * Uses maxims for guidance, whose meaning varies according to the situation 5 Expert * No longer relies on rules, guidelines or maxims * Intuitive grasp of situations based on deep tacit understanding * Analytic approaches used only in novel situations or when problems occur * Vision of what is possible 3 Competent Source: Eraut, M. Developing Professional Knowledge and Competencies. (1994) Milestone Level Definitions Level 1: The resident is a graduating medical student/experiencing the first day of residency. Level 2: The resident is advancing and demonstrating additional milestones. Level 3: The resident continues to advance and demonstrate additional milestones; the resident consistently demonstrates the majority of milestones targeted for residency. Milestone Level Definitions (continued) Level 4: Level 5: The resident has advanced beyond The resident has advanced so that he or she now substantially demonstrates the milestones targeted for residency. This level is designed as the graduation target – not requirement. performance targets set for residency and is demonstrating “aspirational” goals which might describe the performance of someone who has been in practice for several years. It is expected that only a few exceptional residents will reach this level. Milestones Making decisions about readiness for graduation is the purview of the residency program director. What is NAS Driving Us to Do? Change our Evaluations – – – Tagging current evaluation questions to core competencies and milestones Use direct milestone evaluations Or use a combination Ensure our evaluations are valid and reliable measures Overall Milestone Evaluation Approach: Examples EXAMPLE #1: Current Use Current Evaluations EXAMPLE #2: Direct Direct milestone evaluation EXAMPLE #3: Combo Use Current Evaluations Direct milestone evaluation Tag questions to milestones Map questions to milestones Milestones Impact on Evaluations: Linking questions to milestones Step Two: Ensure specific Advises the referring health care provider(s)evaluation about the appropriateness of a procedure in routine clinical situations questions are linked to milestones Example #2 Direct Example # 3- Combined Evaluation Questions Tagged To Milestones Milestones Evaluated Directly Milestone Evaluations demand valid, reliable evaluations as component measurements Unintended bias can impact both direct and indirect milestone evaluations. – – Bias in questions & response scales (existing evaluations) Bias in evaluators (all evaluations) Halo Effect Devil Effect Similarity Effect Central Tendency Self-Fulfilling Prophesy Step 1: Question and Response Scale Construction Two Major Goals: Construct unbiased, focused and nonleading questions that produce valid data Use valid unbiased response scales Step 1: Create the Evaluation-Eliminating Unintended Cognitive Bias What is cognitive bias? Cognitive response bias is a type of bias which can affect the results of an evaluation if evaluators answer questions in the way they think they are designed to be answered, or with a positive or negative bias toward the trainee. Step 1: Create the Evaluation - Where does response bias occur? 1. Response bias can be in the evaluators themselves: Central Tendency, Similarity Effect, First Impressions, Halo Effect, Devil Effect, Self-Fulfilling Prophecy 2. Response bias occurs most often in the wording of the question. Response bias is present when a question contains a leading phrase or words 3. Response bias can also occur in the rating scales. Response Bias in the Raters/Evaluators Beware the Halo Effect The “halo effect” refers to a type of cognitive bias where the perception of a particular behavior or trait is positively influenced by the perception of the former positive traits in a sequence of interpretations. Thorndike (1920) The Halo Effect and Expectations The halo effect is discussed in Kelley's implicit personality theory… – “the first traits we recognize in other people influence our interpretation and perception of later ones because of our expectations…” The Halo Effect Extends to Products and Marketing Efforts Copyright © 2010 Apple Inc. The iPod has had positive effects on perceptions of Apple’s other products…iPhones, etc. Could this impact our evaluations ? GME House Staff Survey 2013-2014 25.67% 19.56% A majority of trainees at Stanford believe that: “The general feeling in my program is that your ability will be labeled based on your initial performance.” 54.77% “Reverse Halo Effect” A corollary to the halo effect is the “reverse halo effect” (devil effect) – Individuals or brands which are seen to have a single undesirable trait are later judged to have many poor traits… - i.e., a single weak point (showing up late, for example) influences others' perception of the person or brand Blind Spots In the 1970s, the social psychologist Richard Nisbett demonstrated that we typically have no awareness of when the halo effect influences us (Nisbett, R.E. and Wilson, T.D., 1977) The problem with Blind Spots is that we are blind to them…now on to self-fulfilling prophesy effect … The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy (SFP) What is the Self-Fulfilling Prophecy? First defined by Robert Merton in 1948 to describe: – ‘A false definition of a situation evoking a new behavior which makes the originally false definition come true.’ The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy (SFP) What is the Self-Fulfilling Prophecy? Has been observed in many processes (Henshel, 1978) Within an individual, as with the placebo response While the placebo effect occurs “within” the individual undergoing treatment, it is important to note that the individual’s belief derives from situational encounters with someone assumed to have expertise. Rosenthal’s Research on SFP For more than 50 years, Robert Rosenthal has conducted research on the role of self-fulfilling prophecies in everyday life and in laboratory situations. – – – Faculty expectations on trainees’ academic and clinical performance The effects of experimenters’ expectations on the results of their research (hence double-blinds) The effects of clinicians’ expectations on their patients’ mental and physical health. The Pygmalion Effect: (Self-Fulfilling Prophesy) Sum it up: the greater the expectation placed upon people, the better they perform Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) reported and discussed the Pygmalion effect in the classroom at length. – In their study, they demonstrated that if teachers were led to expect enhanced performance from some children, then the children did indeed show that enhancement. Pygmalion in Education The purpose of the experiment was to support the hypothesis that reality can be influenced by the expectations of others. This influence can be beneficial as well as detrimental depending on which label an individual is assigned. The observer-expectancy effect, which involves an experimenter's unconsciously biased expectations, is tested in real life situations. – Rosenthal posited that biased expectancies can essentially affect reality and create self-fulfilling prophecies as a result. Pygmalion Effect in Education All students in a single California elementary school were given a disguised IQ test at the beginning of the study. These scores were not disclosed to teachers. Teachers were told that some of their students (about 20% of the school chosen at random) could be expected to be "spurters" that year, doing better than expected in comparison to their classmates. The spurters' names were made known to the teachers. At the end of the study all students were again tested with the same IQ-test used at the beginning of the study. Pygmalion Effect ALL six grades in both experimental and control groups showed a mean gain in IQ from pretest to post-test. – – First and second graders showed statistically significant gains favoring the experimental group of "spurters”. Conclusion: Teacher expectations, particularly for the youngest children, can influence student achievement. Paul Harvey Why ??? Anthropologists have postulated that accurate predictions in our human evolution came to be valued in and of themselves…. Other extensions… “Dani is my shy child…” “Mike never eats his vegetables…” “I can’t see them making much progress…” “Michelle isn’t very coordinated….” “You will feel comfortable and heal very well after this surgery” “I don’t expect Chris to make it through residency, do you?” Quotes… James Rhem, executive editor for the online National Teaching and Learning Forum, commented: "When teachers expect students to do well and show intellectual growth, they do; when teachers do not have such expectations, performance and growth are not so encouraged and may in fact be discouraged in a variety of ways." "How we believe the world is and what we honestly think it can become have powerful effects on how things will turn out." Quotes… Quotes “Do or do not….there is no try” – Yoda Applying these principles to assessments and evaluations… Step 1: Create the Evaluation Question Construction - Exercise One Review each question and share your thinking of what makes it a good or bad question. Question Construction: Exercise 1 Example 1: – Example 2: – “Incomplete, inaccurate medical interviews, physical examinations; incomplete review and summary of other data sources. Fails to analyze data to make decisions; poor clinical judgment.” Example 4: – “Sufficient career planning resources are available to me and my program director supports my professional aspirations .” Example 3: – "I can always talk to my Program Director about residency related problems.” "Communication in my sub-specialty program is good.“ Example 5: – "The pace on our service is chaotic." Question Construction - Test Your Knowledge Example 1: "I can always talk to my Program Director about residency related problems." Problem: Terms such as "always" and "never" will bias the response in the opposite direction. Result: Data will be skewed. Question Construction - Test Your Knowledge Example 2: “Career planning resources are available to me and my program director supports my professional aspirations." Problem: Double-barreled ---resources and aspirations… Respondents may agree with one and not the other. Researcher cannot make assumptions about which part of the question respondents were rating. Result: Data is useless. Question Construction - Test Your Knowledge Example 3: "Communication in my subspecialty program is good." Problem: Question is too broad. If score is less than 100% positive, researcher/evaluator still does not know what aspect of communication needs improvement. Result: Data is of little or no usefulness. Question Construction - Test Your Knowledge Example 4: “Evidences incomplete, inaccurate medical interviews, physical examinations; incomplete review and summary of other data sources. Fails to analyze data to make decisions; poor clinical judgment.” Problem: Multi-barreled ---Respondents may need to agree with some and not the others. Evaluator cannot make assumptions about which part of the question respondents were rating. Result: Data is useless. Question Construction - Test Your Knowledge Example (5): – "The pace on our service is chaotic.“ Problem: The question is negative, and broadcasts a bad message about the rotation/program. Result: Data will be skewed, and the climate may be negatively impacted. Evaluation Question Design Principles Avoid ‘double-barreled’ or multi-barreled questions. Eliminate them from your evaluations. A multi-barreled question combines two or more issues or “attitudinal objects” in a single question. More examples…. Avoiding Double-Barreled Questions Example: COMPETENCY 1 – Patient Care “Resident provides sensitive support to patients with serious illness and to their families, and arranges for on-going support or preventive services if needed.” Evaluation Question Design Principles Combining the two or more questions into one question makes it unclear which object attribute is being measured, as each question may elicit a different perception of the resident’s performance. RESULT Respondents are confused and results are confounded leading to unreliable or misleading results Tip: If the word “and” or the word “or” appears in a question, check to verify whether it is a double-barreled question. Evaluation Question Design Principles Avoid questions with double negatives… When respondents are asked for their agreement with a negatively phrased statement, double negatives can occur. – Example: Do you agree or disagree with the following statement? Attendings should not be required to supervise their residents during night call. Evaluation Question Design Principles If you respond that you disagree, you are saying you do not think attendings should not supervise residents. In other words, you believe that attendings should supervise residents. Phrase the questions positively if possible. If you do use a negative word like “not”, consider highlighting the word by underlining or bolding it to catch the respondent’s attention. Evaluation Question Design Principles Because every question is measuring “something”, it is important for each to be clear and precise. Remember…Your goal is for each respondent to interpret the meaning of each survey question in exactly the same way. Pre-testing questions is definitely recommended! Evaluation Question Design Principles If your respondents are not clear on what is being asked in a question, their responses may result in data that cannot or should not be applied to your evaluation results… Example: "For me, further development of my medical competence, it is important enough to take risks.” Does this mean to take risks with patient safety, risks to one's pride, or something else? Evaluation Question Design Principles Keep questions short. Long questions can be confusing. Bottom line: Focus on short, concise, clearly written statements that get right to the point, producing actionable data. Short concise questions take only seconds to respond to and are easily interpreted. Evaluation Question Design Principles Do not use “loaded” or “leading” questions. A loaded or leading question biases the response the respondent gives. A loaded question is one that contains loaded words. – For example: “I’m concerned about doing a procedure if my performance would reveal that I had low ability” Disagree Agree Evaluation Question Design Principles "I’m concerned about doing a procedure if my performance would reveal that I had low ability" How can this be answered with “agree or disagree” if you think you have good abilities in appropriate tasks for your area? Evaluation Question Design Principles A leading question is phrased in such a way that suggests to the respondent that a certain answer is expected: – Example: Don’t you agree that nurses should show more respect to residents and attendings? Yes, they should show more respect No, they should not show more respect Evaluation Question Design Principles Do use Open-Ended Questions Do use comment boxes after negative ratings – To explain the reasoning and target areas for focus and improvement. General, open-ended questions at the end of the evaluation can prove very beneficial – Often it is found that entire topics have been omitted from the evaluation that should have been included. Quick Exercise #2 1. 2. 3. Please rate the anesthesia resident’s communication and technical skills. Rate the resident’s ability to communicate with patients and their families. Rate the resident’s abilities with respect to case familiarization; effort in reading about patient’s disease process and familiarizing with operative care and post op care Quick Exercise #2 4. 5. 6. Residents deserve higher pay for all the hours they put in, don’t they? Explains and performs steps required in resuscitation and stabilization. Do you agree or disagree that residents shouldn’t have to pay for their meals when oncall? Quick Exercise #2 8. 9. 10. Demonstrates an awareness of and responsiveness to the larger context of health care. Demonstrates ability to communicate with faculty and staff. Demonstrates ability to communicate with faculty and staff. Quick Exercise #2 “Post Test” (1) 1. Please rate the anesthesia resident’s communication and technical skills - Please rate the anesthesia resident’s communication skills. - Please rate the anesthesia resident's technical skills. 2. Rate the resident’s ability to communicate with patients and their families - Rate the resident’s ability to communicate with patients - Rate the resident’s ability to communicate with families Quick Exercise #2 “Post Test” (2) 3. Rate the resident’s abilities with respect to case familiarization; effort in reading about patient’s disease process and familiarizing with operative care and post op care – – – – Rate the resident’s ability with respect to case familiarization Rate the resident’s ability with respect to effort in reading about patient disease process Rate the resident’s ability with respect to familiarizing with operative care Rate the resident’s ability with familiarizing with post op care Quick Exercise #2 “Post Test” (3) 4. Residents deserve higher pay for all the hours they put in, don’t they? – To what extent do you agree that residents are adequately paid? 5. Explains and performs steps required in resuscitation and stabilization – – Explains steps required in resuscitation Explains steps required in stabilization following resuscitation Quick Exercise #2 “Post Test” (4) 6. Do you agree or disagree that residents shouldn’t have to pay for their meals when on-call? – To what extent do you agree that residents need to pay for their own on-call meals? 7. Demonstrates an awareness of and responsiveness to the larger context of health care. – – Demonstrates an awareness of the larger context of health care Demonstrates responsiveness to larger context of health care 8. Demonstrates ability to communicate with faculty and staff. – – Demonstrates ability to communicate with faculty Demonstrates ability to communicate with staff Bias in the Rating Scales for Questions The scale you construct can also skew your data, much like we discussed about question construction but luckily, for us… Milestone Scales use Balanced Scaled Responses… Review your Program’s evaluations with the goal of eliminating any unintentional bias from them. Take a look at the evaluations you use. – – Identify questions which may have unintended bias. Modify questions to eliminate bias Gentle Words of Wisdom - Avoid large numbers of questions…. Respondent fatigue – the respondent tends to give similar ratings to all items without giving much thought to individual items, just wanting to finish In situations where many items are considered important, a large number can receive very similar ratings at the top end of the scale – – Items are not traded-off against each other Many items that not at the extreme ends of the scale or that are considered similarly important are given a similar rating Respondents quit answering questions at all… – – Total Started Survey: 578 Total Completed Survey: 473 (81.8%) Gentle Words of Wisdom Begin with the End Goal in Mind What do you want as your outcomes? Be prepared to put in the time with pretesting. The faculty member, nurse, patient, resident has to be able to understand the intent of the question - and each must find it credible and interpret it in the same way. Gentle Words of Wisdom: Relevancy/Accuracy – Collect data in a valid and reliable way If the questions aren’t framed properly, if they are too vague or too specific, it’s impossible to get any meaningful data. Question miswording can lead to skewed data with little or no usefulness. If you don't plan or know how you are going to use the data, don't ask the question! Summary: Evaluation Do’s and Don’ts DO’s Keep Questions Clear, Precise and Relatively Short. Use a balanced response scale – Milestone scales are balanced Use open-ended questions DON’Ts Do not use Double+ Barreled Questions Do not use Double Negative Questions Do not use Loaded or Leading Questions. Questions Please feel free to contact us with any questions @ 650-723-5948 npiro@ stanford.edu or adohn1@stanford.edu Stanford University Medical Center Graduate Medical Education