dowdy… …than gaudy

Sparrow

‘Sparrow’

Norman MacCaig

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Negative comment. First thing we learn about the sparrow is something he is not.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

This sets the tone for the rest of the poem… dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

‘artist’ has connotations of colour, creativity, dexterity, finesse, flamboyance, etc… dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Right from the opening line, the sparrow’s ‘skills’ are deemed unworthy.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Another negative comment. Now his appearance is being criticised… dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

His ‘clothes’ are his feathers.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

They are referred to as ‘more dowdy than gaudy’.

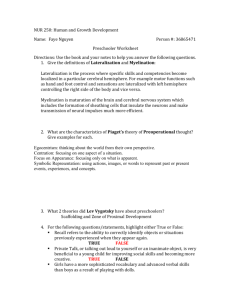

Dowdy: not stylish; drab; old-fashioned; unfashionably dressed.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

They are referred to as ‘more dowdy than gaudy’.

Gaudy: extravagantly bright or showy; ostentatiously dressed.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

He is ‘dressed’ in dull colours of brown and grey.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

He is hardly the most fashionable of creatures.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

more dowdy…

…than gaudy

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Keep in mind the negative connotations of the word ‘gaudy’ for later in the poem… dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Now the sparrow’s home is criticised too… dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Now the sparrow’s home is criticised too… dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

The bird’s home, according to the blackbird at least, is referred to as “a slum”.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Slum: a squalid section of a city, characterised by inferior living conditions.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

The image of the sparrow’s home is therefore one of poverty, squalor and decrepitude.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Only the poorest, most common bird would live there.

dowdy than gaudy.

A blackbird wouldn’t want to be associated with such a habitat.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Remember, the nest is the handiwork of the sparrow himself.

Therefore, his ability to build a home is being derided too.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Of course, this isn’t the only way in which the sparrow and blackbird differ… dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

The male blackbird is, unsurprisingly, fully

‘clothed’ in black. Its beak is a bright orangeyellow colour.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

This, according to the

RSPB, “make adult male blackbirds one of the most striking garden birds.” dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

As a result, the metaphor of the blackbird’s beak being the gold nib of a pen is understandable.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

A nib is the end of a fountain pen.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

The movement of the bird, as it flies through the air, is comparable to a pen writing decoratively in the air.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

The image tells us a lot about the blackbird itself… dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

The comparison to a fountain pen, for example, which is seen more as a luxury item and used by many as a status symbol.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

A biro, for example, is much cheaper and efficient but doesn’t project a superior image.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

It’s a case of style over substance. The value is judged on appearance and status, not ability or capability… dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

…which is key to the central concern of the entire poem.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

The fact that the nib is gold accentuates the idea of affluence of the blackbird.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

A bird with gold certainly wouldn’t be seen dead in a slum… dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Fountain pens are used for calligraphy

(decorative handwriting).

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

Calligraphy itself is considered an art.

This is another direct contrast to the sparrow

(“he’s no artist”).

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

The writing the blackbird produces is ornate and attractive.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Calligraphy is used on wedding invitations, award, certificates, etc. because of its beauty, but also to emphasise the importance of the contents.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

“Pretty scrolls” continues the idea of ornate, decorative writing.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Scrolls are not written on for everyday purposes.

dowdy than gaudy.

Again, form over function.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

Also, the first thing I think of when I see the word “scroll” is the certificate you are awarded at your graduation ceremony. dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

Awards and qualifications for academic success are something that we will return to later in the poem…

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

This stanza begins by making the sparrow seem insignificant.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

He isn’t deft or elegant in his movements.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

His feathers are from bright or decorative.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

His nesting habits are decidedly basic.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

The message given is that there is nothing noteworthy or glamorous about the sparrow at all.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

The colloquial, informal

“he’s no artist” introduction seems appropriate for the sparrow.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

The sparrow is common.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more

He certainly doesn’t command, or perhaps demand, attention like the blackbird does.

dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

He’s no artist.

His taste in clothes is more dowdy than gaudy.

And his nest – that blackbird, writing pretty scrolls on the air with the gold nib of his beak, would call it a slum.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

A large number of techniques are used throughout this second stanza…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Unlike the opening to the first stanza, when we were introduced to the sparrow, there is a formality to the language used here.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Repetition is prevalent through these three lines…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Each line begins in the same way…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Each line begins in the same way…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Each line begins in the same way…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Each line begins in the same way…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Each line begins with infinitives (basic form of a verb – to run, to fly, etc).

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The verbs used are grand and graceful.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

“To stalk” is to walk in a stiff, arrogant way. Therefore, there are connotations of superiority and grandeur.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

“To sing” is obviously a graceful, artistic activity.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

“To glide” is to move in a smooth, effortless way. Again, a very graceful, artistic movement. There’s no frantic flapping of wings from these birds.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The repetition of these infinitives serve as a contrast to the sparrow being “no artist”.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Continuing the parallel structure of these three lines, the word “solitary” follows each of the infinitives.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Continuing the parallel structure of these three lines, the word “solitary” follows each of the infinitives.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Continuing the parallel structure of these three lines, the word “solitary” follows each of the infinitives.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Continuing the parallel structure of these three lines, the word “solitary” follows each of the infinitives.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Solitary: alone; without companions.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The repetition of the word “solitary” emphasises the isolation and aloofness of certain birds.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

They do not wish to be seen with other birds. They want to command attention in their own right.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

They may be graceful and elegant, but these birds are left isolated as a result of their attitude.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

They may be graceful and elegant, but these birds are left isolated as a result of their attitude.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The parallel structure continues with the repetition of prepositional phrases…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The parallel structure continues with the repetition of prepositional phrases…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The parallel structure continues with the repetition of prepositional phrases…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The parallel structure continues with the repetition of prepositional phrases…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Obviously, these are three of the locations where the ‘stalking’, ‘singing’,

‘gliding’ birds can be found.

However, it is notable that these areas grow in size…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The ever-increasing areas emphasise the isolation of these birds…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Being in solitude on a lawn is one thing, being in solitude while gliding over something as vast as the Atlantic is quite another.

The greater the area, the greater the isolation is…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

As mentioned earlier, the language used to refer to these other birds is very formal.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

These lines appear to be building to a climax. Each line increases in length and the descriptions build from stalking over a lawn to gliding over the Atlantic ocean.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

At this point, a dash is used…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

At this point, a dash is used…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The dash introduces a dramatic pause, as though the finale is going to be even grander than the bird that glides over the Atlantic…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Instead, what follows the dramatic pause is a huge anti-climax, as the focus returns to the humble sparrow…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Instead, what follows the dramatic pause is a huge anti-climax, as the focus returns to the humble sparrow…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

After the grand descriptions of actions of other birds, what follows is a blunt, simple statement of “not for him”.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

This is extremely effective, as it reflects the simple nature of the sparrow itself.

There is nothing formal or grand about the sparrow, so why should the language be any different?

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To further emphasise the contrast between the grander birds and the sparrow, MacCaig offers a description of what the sparrow can be found doing…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

We are told that the sparrow would

“rather” be involved in a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The sparrow would happily be involved in a fight. It isn’t something he would flee from in fear. He would happily scrap for what he believes is necessary.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

There could not be a greater contrast used here.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The other birds’ actions (stalking singing and gliding) are grand and graceful…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

…while the sparrow’s actions are violent and coarse.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The other birds’ actions are described using formal language…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

…while the sparrow’s actions are described using a colloquial term:

“punch-up”.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Even the location is in sharp contrast to the earlier references…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Even the location is in sharp contrast to the earlier references…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

While a gutter is simply a channel at the edge of a street or road, or a trough under a roof for draining rainwater (places where it would be quite conceivable to find a sparrow fighting other birds for scraps of food)…

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

…it also has very negative connotations of a dirty, degrading place where the lowest classes of humanity end up.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

It’s also a very informal, colloquial term.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

Indeed, the whole sentence is structured to directly contrast with what came before.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

As well as the blunt “not for him” and the colloquial “punch-up” and “gutter”, there is the shortened, conversational “he’d”.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

As well as the blunt “not for him” and the colloquial “punch-up” and “gutter”, there is the shortened, conversational “he’d”.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

The informal word choice and sentence structure reflect the ordinary nature of the sparrow.

To stalk solitary on lawns, to sing solitary in midnight trees, to glide solitary over grey Atlantics – not for him: he’d rather a punch-up in the gutter.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

The third stanza focuses on the sparrow’s apparent lack of education…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

MacCaig suggests that the sparrow economises in what he knows. In terms of learning, it has retained very little.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

Again, MacCaig effectively uses poetic techniques to emphasise the point being made…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

Again, MacCaig effectively uses poetic techniques to emphasise the point being made…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

The word “lightly” stands out for a number of reasons…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

Firstly, placing the adverb “lightly” at the end of the clause makes it more notable.

(compare: ‘he carefully opened the box’ / ‘he opened the box carefully’)

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

MacCaig effectively uses enjambment to further emphasise his point…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

Enjambment: the running over of a sentence from one line of verse into the next.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

As a result, the word “lightly” now appears at the start of the next line. Followed by a dash, the word stands out for all to see.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

MacCaig is emphasising that the sparrow is not weighed down with learning. It retains very little of what it has been educated in.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

After stating that the sparrow economises in what he knows, MacCaig identifies the learning that the sparrow retains.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

The sparrow retains only what is useful for day-to-day survival.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

The sparrow does not have the academic ability of the other birds. Therefore, he has to be selective with the information that he retains.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

He judges the worth of what he learns by how useful it is.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

He judges the worth of what he learns by how useful it is.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

Skills such as the ability to glide, to sing, to write pretty scrolls in the air may be impressive, but they are not practical skills that are necessary for survival.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

In other words, they are not useful.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

“result”, found at the end of the line, is very notable…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

“result” continues the idea of academic performance: results from the examinations we sit when being assessed on our academic ability.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

However, the only “result” the sparrow is interested in is survival. He is not concerned with his ‘results’ in singing or gliding…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

However, the only “result” the sparrow is interested in is survival. He is not concerned with his ‘results’ in singing or gliding…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

The stanza concludes with a couple of short, negative sentences, reflecting the simple, ordinary nature of the sparrow…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

Both sentences are minor sentences as they are lacking a verb or verb phrase (so technically not proper sentences). Therefore, they continue the informal language used when referring to the sparrow.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

The sparrow is described as being a

“proletarian” bird…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

Proletarian: belonging to the lower or working class; the class of wage-earners whose only possession of significant material is their labour.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

Again, this is an effective description. The sparrow is common. If a human, he most certainly would be considered working-class.

He does not have the education, skill or grace required to be part of the upper classes.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

The stanza ends as the poem began – a simple, negative statement of what the sparrow is not.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

Sandwiched between being identified as “no artist” and “No scholar”, the sparrow’s appearance, skills and learning have all been looked down upon.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

At this point, the poem appears to have been rounded off quite nicely…

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

He carries what learning he has lightly – it is, in fact, based only on the usefulness whose result is survival. A proletarian bird.

No scholar.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

However, the opening word of the fourth stanza introduces a change in direction.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The first three stanzas may not have compared the sparrow favourably to the other birds, but the “But” suggests that this may be about to change…

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

MacCaig effectively uses personification when referring to the arrival of winter…

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

MacCaig describes winter as soft-shoeing in. This makes it sound secretive, as though winter has crept up behind the birds without them noticing.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The use of sibilance adds to the image of winter softly creeping in…

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The use of sibilance adds to the image of winter softly creeping in…

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

Sibilance: repetition of the

‘s’ or ‘sh’ sound.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

This is quite an apt image, as winter quite often creeps up on us without any warning…

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

There is also irony in the fact that soft-shoe is a type of dance.

Soft-shoe is a silent version of tap-dancing.

Soft shoes are worn by highland dancers.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

There is also irony in the fact that soft-shoe is a type of dance.

Soft-shoe is a silent version of tap-dancing.

Soft shoes are worn by highland dancers.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

Parenthesis is effectively utilised by

MacCaig here…

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The other birds are identified as

“ballet dancers, musicians, architects”.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The “ballet dancers” are the graceful birds who glide in flight. Both have great poise and beauty in their movements.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The “musicians” are the birds who make beautiful ‘music’ with their songs.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The “architects” are the birds who build impressive nests.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

These are very effective images of the different birds.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

MacCaig expertly guides the reader into seeing the comparison between birds and mankind.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

“ballet dancers, musicians, architects” are seen as highfliers (sorry, couldn’t resist!).

They are certainly not jobs held by the working-class.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The change in direction is revealed.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The other birds, despite all their grace and beauty, are the ones who fail to survive the harsh conditions of winter.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The image of birds dying in the snow and being frozen to braches is harsh is itself.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

These birds may have beautiful songs and glide majestically across the sky, but they do not have the practical skills necessary to survive.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

This reflects society itself.

Some people have beauty and graceful movements, but they don’t have the practical skills necessary to deal with the harsh realities of life.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

Once again,

MacCaig utilises the contrast between the sparrow and the other birds…

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The sparrow, unlike the other birds, manages to survive the winter.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

He has the practical skills necessary to survive the harsh conditions.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

The learning he carries lightly has proved to be more important than skills that the other birds enjoy showing off.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

MacCaig once again makes reference to education and academic performance.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

MacCaig once again makes reference to education and academic performance.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

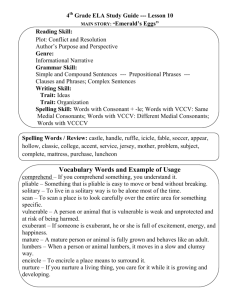

O-levels and Alevels are qualifications earned by pupils at school. Our current equivalent would be Standard

Grades and

Highers.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

There is a humorous irony used here. The sparrow is far from the brightest bird in terms of the

‘academic’ skills that it has.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

It wouldn’t achieve A-level music or A-level writing, that’s for sure.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

However, if practical skills were assessed, the sparrow would pass quite comfortably.

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

Indeed, he would pass with

‘flying’ colours!

(sorry…)

But when winter soft-shoes in and these other birds – ballet dancers, musicians, architects – die in the snow and freeze to branches, watch him happily flying on the O-levels and A-levels of the air.

Commentary…

Sparrow begins by making the bird seem insignificant.

Words like “dowdy” and “slum” suggest that there is nothing noteworthy or creative about the sparrow’s plumage or nesting habits. The poet continues to emphasise the ordinary nature of the sparrow in the colloquial language that one of this type might use: “a punch-up in the gutter”. By contrast, the blackbird demands attention in his writing in the air; the words “pretty scrolls” and the image of the

“gold nib” of a pen (beak) suggest ornate writing which is attractive.

This slang contrasts to the formality of the first three lines of stanza two in the repeated structure of “to stalk”, “to sing” and “to glide”. Each of these infinitives emphasises the isolation of grander birds who cover spaces which grow increasingly larger – from lawns to trees to “grey

Atlantics”. The poet suggests that the sparrow economises in what he knows – keeping with him only what is useful for day-to-day survival.

The position of the word “lightly” at the beginning of line thirteen emphasises this quality and “proletarian” reinforces the idea that the sparrow is common, one of the masses. Finally, the short negative phrase

“No scholar” at the end of stanza three leaves the reader in no doubt about the absence of academic achievement in the bird. The brevity of this phrase and its position at this point in the poem summarises what has been expressed in the first three stanzas and harkens back to the first line: the sparrow is “no artist” but it is ordinary in its appearance, its way of life and its accomplishments.

However, the word “but” signals a change in the direction and ideas of the poem. Once again, the poet invites us to compare the sparrow to other more accomplished birds – artists of air and space, “ballet dancers, musicians, architects”. These birds can charm by their flight, by their songs and even by the way they construct their nests. The personification of winter as a secret enemy, emphasised in the sibilant sounds of words “softshoes”, introduces the element of danger. The sinister and sudden appearance of winter is followed by words with bleak connotations. The pictures of birds dying in the snow or, even more dramatically, freezing to death on branches reminds us that the practical skills of survival have their own value.

The poet ends on a lighter note with the sparrow, again in contrast to other birds, surviving happily in the testing times of winter. The “O-levels and A-levels of the air”, as well as other expressions like “punch-up in the gutter” and

“proletarian bird”, and even some of the exaggerated contrasts, remind us that the tone here is a bit tongue-incheek. The poet is not offering us a serious lesson to take to heart; just a suggestion that maybe some practical skills are as important at the end of the day as aesthetic, creative, scholastic accomplishments. After all, daily survival is the essential ingredient for life before we begin decorating our existence with scrolls and songs.

MacCaig effectively uses word choice, images and structure to establish a contrast between the sparrow and other birds. The sparrow, lacking in grace or beauty, has the practical skills to survive when conditions become tough. He is happy to scrap for food, even if that means “a punch-up in the gutter”, in order to survive the winter.

The comparison between birds and mankind is clear in this poem. Many people are blessed with beauty, aesthetic skills and academic ability. They are decorated with awards as a result. Some may become arrogant and aloof as a result. However, the awards are meaningless if they do not have the practical skills to survive life.