hewlett-and-roulette-final-3-27-2013

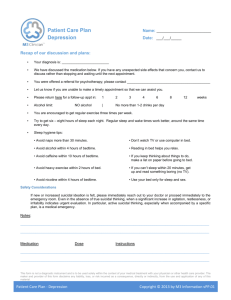

advertisement