Psychologists have been trying to determine why individuals do

Psychologists have been trying to determine why individuals do what they do since Wilhelm Wundt, the father of psychology, started this practice in the mid

1850’s. There have been a countless number of schools of psychology that have been created since then, with different approaches and theories for such abstract studies. These studies can be related to a much broader spectrum – a society, perhaps – to understand why groups, villages, or even entire countries collectively do what they do. Abraham Maslow, a profound American psychologist who approached psychology from a Humanistic point of view, and his theories of the

Hierarchy of Needs have been used to approach both the study of individuals and groups of societies alike, giving us insight on why societies – or in the case of our study, dystopian societies – rise, fall into the arms of corruption, and eventually crumble. Dystopian societies have been both fabricated in works of fiction such as the 2010 motion picture Book of Eli and the novel The Hunger Games, but they have also been products of real human configuration in societies such as the late Soviet

Union. The creators of Book of Eli and The Hunger Games model their societies after that of the Soviet Union in an argument that in the pursuit – and failure in this pursuit – of the first level of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (which we will learn to be the physiological needs of humans), societies to evolve into dystopias over time.

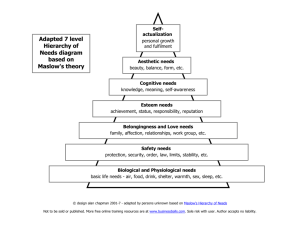

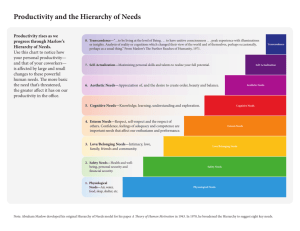

In 1943, Maslow published his Hierarchy of Needs in A Theory of Human

Motivation, a work that revolved around the basic innate goals – or needs – of humans. Maslow separated these needs into five categories: Physiological (general health), safety (shelter), belonging (love), esteem, and self-actualization. In order for an individual to move up the hierarchy, according to Maslow, the individual must

satisfy the needs of the preceding level. Maslow states that mankind is “a perpetually wanting animal” and that we are consistently pursuing these goals, no matter the cost (Maslow). The physiological sector of Maslow’s Hierarchy is concerned with the most basic health needs. Water and food along with sleeping, breathing and homeostasis make up these needs. For our study of dystopian societies, we will focus solely on the lack of food and water within a society and the pursuit of these essentials that leads societies to become dystopian in nature.

There are many individuals that cannot even meet the physiological needs – the first level – on their own. The basic health needs that most likely are unattainable are a sustainable food source and clean water. These individuals must independently resort to some desperate action such as theft or murder to satisfy this motivation. But what happens when entire societies cannot meet the first sector of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs? These entire societies cannot collectively steal and kill other societies to obtain food and water, so, according to Maslow, they must turn to something else, putting their livelihood in the hands of an untested idea or an unfit person in an act of pure desperation, which will undoubtedly fail.

When societies as a whole continually pursuit but fail to satisfy physiological needs, the society will eventually turn dystopian.

In order to classify societies as dystopian, we must define a dystopia. April

Spisak, a critic of dystopian novels, defines a dystopia as

A society that is a counter-utopia, a repressed, controlled, restricted system with multiple social controls put into place via government, military, or a powerful authority figure. Issues of surveillance and invasive technologies are often key, as is a consistent emphasis that this is not a place where you’d want to live. (Spisak)

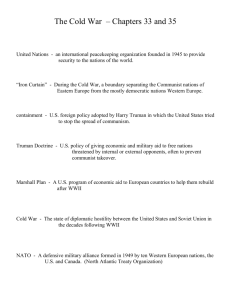

There are countless examples of societies failing to provide the physiological needs for their people followed by the societies evolving into dystopias. One of these instances is the Soviet Union. In the Soviet Union, post-World War I and II depression lead to a scarcity of all resources, especially food. This shortage of food implies that the Russians failed to meet the first level of the Hierarchy. Russia then turned to communism, an ideal founded by Karl Marx along with Friedrich Engels in their 1848 publication of The Communist Manifesto, to try to cope with this shortage.

With communism in place, the people of the USSR hoped and expected the government to issue food – as well as money – equally around the commune.

Together, the fundamentals of communism and the way in which those in power in the Soviet Union practiced the theory exposed true flaws in the system; the implementation of communism in pursuit of the first level of Maslow’s Hierarchy led to a dystopian society.

The lack of communal interest in the Soviet Union created a dystopia. This lack of interest in society as a whole was the true flaw in the theory of communism.

The Soviet Union originally successfully advanced the proletariat by demanding an increase in industrial output, but were also successful in making private entities directionless, where employees and employers had equal say. When this happens, the incentive for quick, efficient, and meaningful production is tossed to the wayside, for one will not be fired or replaced as long as he produces the bare minimum. In producing the bare minimum and not trying to exceed expectations, we see the reality that humans will always work for their self-interest rather than that of their society. Philosopher John Locke describes this self-interest in his 1698

work The Two Treatises of Government when he states that a man will, “do whatsoever he thinks fit for the preservation of himself” (Locke). The lack of selfinterest is the reason an economy collapses under a communist government, simply because a workingman fails to work his hardest when he receives equal pay for producing a poor product and a perfect product. In the USSR, the high presence of poorly produced goods, or the lack of production all together, results in economic turmoil and a scarcity of basic needs. By trying to pursue the physiological needs of society, the Russians turned to communism, an untested idea that failed to satisfy the necessities of its people. By definition, this scarcity of resources is one aspect that allows the Soviet Russian society to be identified as dystopian.

Along with the lack of self-interest in the USSR came equal salary among workers – the so-called “distribution of wealth” (Marx & Engels). This concept is disastrous. Unskilled factory workers and highly trained doctors were issued equal rights and benefits within the Soviet Union. A young, intelligent man in Soviet society had absolutely no incentive to become a doctor instead of a factory worker.

This created both a surplus of factory workers, otherwise known as unemployment, and a shortage of skilled labor. Even though there was a surplus of factory workers, the lack of incentives caused abysmal production, creating “food shortages and worse production shortages” (CIA World Factbook). These shortages within a stagnant economy are a key component as to what made the communist society of the Soviet Union a dystopian society. The poor economy under the communist regime in the Soviet Union only account for half of what made the untested government system turn society into a dystopia. The other half, and quite possibly

the more important half, is the social factors of this government that is put into place in the pursuit of physiological needs.

Constant censorship and surveillance of citizens by the government existed under the communist regime of Soviet Russia. When private property is eliminated, the government disregards personal privacy as well. In an article published in 2001 by Valeria Stelmakh titled “Reading in the Context of Censorship in the Soviet

Union,” Stelmakh states,

The regime’s attempts to forestall the impending collapse and to stabilize the situation included strengthening censorship and other repressive measures. At this time, the society has been living under an almost complete blockage on information combine with a sophisticated system of misinformation and total censorship. (Stelmakh 144)

This insight to why the Soviet Union’s government shows the contribution of censorship, oppression, the providing of false information, and the prevention of outside information entering society shows its development to dystopian society.

The cruel ways of the governments in the Soviet Union and in the village fit Spisak’s dystopian earlier description as they are both experience a, “repressed, controlled, restricted system with multiple social controls put into place via government, military, or a powerful authority figure” (Spisak). Pulitzer Prize recipient Judith

Miller notes an additional oppressive nature of the Soviet regime when she states,

“In the Soviet Union, communists…purged their libraries of objectionable works”

(Miller). Communists burned these books in order to eliminate books that promoted ideas of the West, thus expose citizens to only the communist way of life, and remove the temptation to be in a different society. The elimination of books is yet another example of the oppressive and surveillance-minded nature of the

governmental authority in the Soviet Union, the government that was implemented in the pursuit of the first level of Maslow’s Hierarchy, once again fitting the earlier description of a dystopian society.

Additionally, when the government owns all property, such as in the USSR, the privacy of civilians is obliterated and the ability for the government to do whatever it pleases skyrockets. This is where the extreme surveillance and oppression come into play once more, causing the communist regime the people turned to in pursuit of their physiological needs to become a dystopian society. The surveillance and oppression by the governments were just part of the social turmoil that existed in Soviet Russia. Social disorder came in many forms within the USSR, simply because the first level of the Hierarchy was not being met.

Gary Whitta, the writer of the Book of Eli, argues that the village that Eli

Walker arrives in while searching for water models the USSR. Whitta argues that in pursuit of the physiological needs that were not met earlier, the society becomes a dystopia.

The people of the United States are left without resources after presumable nuclear warfare strips the land of its nourishment – as well as most of its population. The few remaining survivors choose to gather in small towns or live on their own from a day-to-day basis. Both parties have a lack of food and water, both of which are essential in the first stage of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. The individuals have an easy solution: hunt, kill, and steal from anything in the way of food and water. Sometimes, this means cannibalism, which according to Maslow will still satisfy the need for food. The pop-up towns of survivors, however, have much

greater difficulty in finding food in water, given their seclusion from other societies.

The village that Eli finds comes across this problem. Instead of turning to hurting others, though, the society turns to a man named Carnegie. This absolute act desperation is in search of a savior from starvation and thirst. Carnegie in turn takes the already scarce food, water, and other resources for himself, using most of the resources for himself and his men, and then distributing the remainder scarcely.

The majority of the village suffers from consistent famine while he sits atop his throne with an abundance of water and food. Such an action is similar to that the

USSR did in their 20 th century regime. With the lack of private property, the government collected and distributed food as they saw fit, often overcompensating in some areas and undercompensating in others, leaving many to starve however,

“members of the Party ha[d] long been able to buy western goods and food in special party shops” (Angelfire). Because the Party members were able to buy western food and other goods, they put themselves in a better state than they put their people in. The selfishness of the communist party leaders in Soviet Russia reflects that of the Carnegie.

Carnegie’s corruption after taking over the reign of the village leads not only a starving town, but an oppressed town. Carnegie expresses his desire to have the villages completely under his thumb when he states, “It’s not a fucking book! It’s a weapon! A weapon aimed right at the hearts and minds of the weak and the desperate. It will give us control of them” (Whitta). Carngie is pursuing the control over the people similar to the control the communist regime of the Soviet Union had over theirs.

The collapse of Carnegie’s regime begins when his girlfriend, Claudia, leaves him after he is unable to attain the knowledge of the Bible. Immediately following, his become chaotic in his bar and on the streets, further defining the demise of

Carnegie’s rule. The people of the village give up on Carnegie as their new ruler after he fails to provide them with food and water, and although the viewers never see what ensues in the village, according to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the villagers will search for a new leader to hopefully fulfill this need for them, or leave the village to do it themselves. The collapse of Carnegie’s reign mirrors that of the collapse of the government of the Soviet Union. The people of the Soviet Union were extremely unsatisfied, especially with the scarcity of food and other necessary resources. After cycling through numerous communist leaders, the USSR fell in

1991.

Susan Collins, author of The Hunger Games also argues that the pursuit of the first stage of the Hierarchy of Needs led Panem to become a dystopia similar to the

Soviet Union. North America, which is now called Panem, is under distress after some unknown apocalyptic event. The population is much more scarce than usual.

Only 12 Districts remain, which are relatively small in nature, and all survivors are contained in these Districts. With any existing government eliminated by this apocalyptic event, the new government – the Capitol – takes control of existing

Panem to provide order, and more importantly food and water, to the population.

This is again is extremely similar to the Soviet Union’s rise to power. While the rise to power of the communist party did not occur after an apocalyptic event, it did happen after World Wars I and II, leaving the Soviets hurt in both population and

resources. The goal of the communist party was to steer away from existing regimes, thus providing a new, improved order and food distribution strategy.

Much like in the Soviet Union, the Capitol abuses the power, giving an unfair majority of resources and privileges to itself and Districts 1, 2, and 3. This unfair distribution of food is evident when Katniss narrates “District 12 – where you can starve to death in safety” (Collins). The remainder of the Districts are justly frustrated with this recurring theme in resource distribution and rebel in order to get their hands on the supplies they were missing out on – and thus satisfy their physiological needs of the Hierarchy. The rebellion is crushed and even harsher restrictions are placed on the Districts, such as the implementation of the Hunger

Games, as a reminder of the uprising. The Capitol reigns for quite some time, but, just as we saw in the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Capitol is eventually broken down after not being able to provide basic needs for its people.

Both Gary Whitta, writer of Book of Eli, and Susan Collins, author of The

Hunger Games, argue that the pursuit of the first level of Maslow’s Hierarchy of

Needs causes a dystopia within societies, assuming that the first level of the

Hierarchy was not met previously. In both works of fiction, societies elected or conceded to following a new form of government or order, in the pursuit of essentials such as food and water. When resources such as food and water are sparse, those in control of the resources will undoubtedly abuse their control, taking the essentials for their own well being before thinking of the people for whom they must provide. This leads to healthy lives for members of the government and a hunger-stricken remainder of society. After the leadership realizes how desperate

their civilians are for food and water, it will manipulate its people into doing anything for these resources. We saw this take place in Book of Eli when Carnegie sends his men to search the entire country for a Bible in return for water and food, in The Hunger Games when the Capitol makes the Districts send volunteers to the

Games for their own entertainment, and in the Soviet Union when the members of the communist party possessed food and other goods from the West that they banned for the rest of society.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs comes into play in these situations. The people in these societies allow themselves to be manipulated in return for food and water in the pursuit of fulfilling their physiological needs. Both of these writers chose to model their societies after the Soviet Union, a real-life example showing how the pursuit of physiological needs will lead to a dystopia. Extremely similar events happen in the rise and fall of the village in Book of Eli, the Capitol’s regime in The

Hunger Games, and the communist regime of the Soviet Union, from the rise to a new power in desperation to find food and water, to the abuse of the power the leadership is given, to the cyclical unhappiness of civilians, and, ultimately, the demise of the society, making it a dystopia by definition.

The definition of a dystopia contains two parts, a shortage of necessary resources, as well as a harsh governing power. It has been made clear that the people in the USSR, the village civilians of Book of Eli, and the District population of

Capitol in The Hunger Games suffered from a large scarcity of necessities such as food and water – resources that would fulfill physiological needs according to

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. The other half of defining a dystopian society is with

regards to the leadership and its brutality. Surveillance has a strong presence in defining a dystopia, according to Spisak, and this is evident when her definition of a dystopia states “issues of surveillance and invasive technologies [were] often key”

(Spisak). All three societies that we have been studying experience the same progression to omnipresent leadership turning into dystopian leadership. In Book of Eli, Carnegie comes to power, but fails to provide essentials for his people, much like how both the Soviets and the Capitol in Hunger Games fail to provide essentials for their civilians.

None of the three governing powers succeed in keeping their people happy by not meeting Maslow’s first level, and, naturally, their people begin think of rebellion and eventual overthrow. To combat this, the leadership used different techniques of surveillance on their civilians. The Capitol introduced Jabberjays to report and conversations the Districts were having back to them, the Soviets used the KGB to spy on potential traitors and revolution catalysts, and Carnegie uses his men to take the books of all civilians in addition to using Solara as a hybrid prostitute/spy when Eli spends the night in his quarters.

We see how leadership uses the physiological needs of its people to manipulate them. The fact that there is a shortage of necessities such as food and water, coupled with the fact that the governance of society uses this shortage as a means to manipulate, restrict, and oppress its people allows us to identify all three of the societies mentioned above as dystopian.

The writers of Book of Eli and Hunger Games argue that the pursuit of the first stage of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs leads to a dystopia, as we saw in the

collapse of the Soviet Union in the 20 th century. Karl Marx once compared his ideal communist society, such as the Soviet Union, to that of a beehive. The people of a communist society act as worker bees. They were to have no incentive to work as hard as they possibly could other than to improve the beehive – their society – and satisfy the queen bee – the communist government. In a perfect world, a communist government would drive a utopian society, but as the world saw with the collapse of the USSR, the pursuit of the first level of the Hierarchy and the desperate implementation of communism was the force behind something quite the opposite: a dystopia.

The Soviet Union collapsed more than two decades ago, but the knowledge that this government modeled a utopia and turned dystopian so quickly in the pursuit of the physiological needs makes one wonder, what do the bees know that we don’t? How can the smartest animals on the planet destroy a utopia in half a century, or in the village of Book of Eli’s case, 30 years, and in the Capitol’s case, 50 years, while mindless insects have operated cooperatively under this regime for millions of years, and when will mankind figure it out?