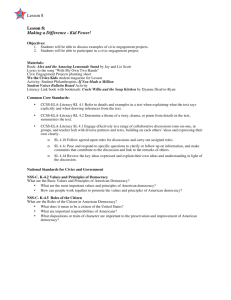

Dechen Rabgyal

advertisement