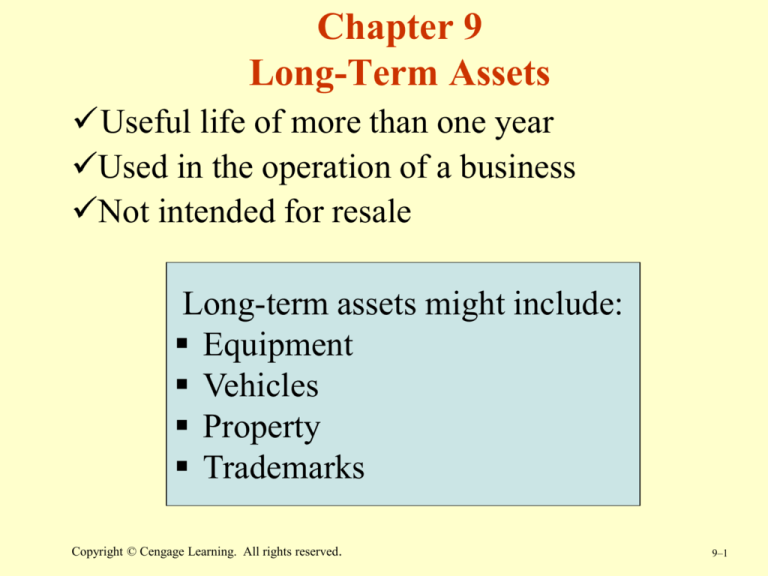

Chapter 9

Long-Term Assets

Useful life of more than one year

Used in the operation of a business

Not intended for resale

Long-term assets might include:

Equipment

Vehicles

Property

Trademarks

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–1

Carrying Value

The unexpired cost of an asset

(also called book value)

Unexpired Cost = Cost – Accumulated Depreciation

On the Balance Sheet:

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–2

Classification of Long-Term Assets and Methods

of Accounting for Them

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–3

Asset Impairment

When is an asset

deemed impaired?

When a long-term

asset loses some or all

of its potential to

generate revenue

before the end of its

useful life

Asset Impairment

The carrying value of a

long-term asset exceeds

its fair value

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–4

Acquiring Long-Term Assets

How do companies make the decision to

acquire long-term assets?

Capital Budgeting

Method of Evaluation

Net Present Value Method

Evaluates the purchase

based on the net present

value of acquisition cost, net

annual savings in cash

flows, and disposal price

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

© Royalty-Free/Corbis

9–5

Net Present Value Method Illustrated

Apple Computer is considering the purchase of a $100,000 customer

relations software package. Management estimates that the company will

save $40,000 in net cash flows per year for four years, the usual life of the

software. The software should be worth $20,000 at the end of that period.

The interest rate is 10 percent compounded annually.

Cash flows related to the purchase of the computer would be as follows:

Acquisition cost

Net annual savings in cash flows

Disposal price

Net cash flows

20x5

($100,000)

$40,000

20x6

20x7

20x8

$40,000

$40,000

($60,000)

$40,000

$40,000

$40,000

20,000

$60,000

Present value Tables 1 and 2 can now be used to place the

cash flows on a comparable basis.

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–6

Example of Net Present Value Method

(hwk E4)

Acquisition cost

Net annual savings in cash flows

Disposal price

Net cash flows

Acquisition Cost

20x5

($100,000)

$40,000

20x6

20x7

20x8

$40,000

$40,000

($60,000)

$40,000

$40,000

$40,000

20,000

$60,000

Present Value Factor = 1.0

($100,000)

Net Annual Savings Present Value Factor = 3.17

Cash Flows

Table 2: 4 Periods, 10%

3.170 X $40,000

$126,800

Disposal Price

$13,660

Present Value Factor = 0.683

Table 1: 4 Periods, 10%

0.683 X $20,000

Net Present Value

As long as the net present value is

positive, Apple will earn a return of at

least 10 percent.

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

$39,600

The return is greater than 10 percent on

the investment. Based on this analysis,

Apple should purchase the software.

9–7

Financing Long-Term Assets

• Financing

alternatives:

Use cash flow from

operations

Issue common stock

Issue long-term notes

Issue bonds

Investors may investigate

whether a company has

free cash flow to finance

long-term assets.

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

© Royalty Free PhotoDisc Collection/ Getty Images

Free cash flow is cash that

remains after deducting funds

committed to operations at

current levels

9–8

The Matching Rule and

Long-Term Assets

When a company purchases an asset, it may choose to

capitalize it, thus deferring an expense to a later period

Favorably impacts profitability for that current period

Management must use ethical judgments when

resolving two issues:

1. How much of the total cost of a long-term asset

should be allocated to expense in the current

period?

2. How much should be retained on the balance sheet

as an asset that will benefit future periods?

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–9

Long-Term Asset

Accounting Policies

Each company must determine how it will

treat long-term assets:

1. How is the cost of the long-term asset

determined?

2. How should the expired portion of the cost of the

long-term asset be allocated against revenues

over time?

3. How should subsequent expenditures, such as

repairs and additions, be treated?

4. How should disposal of the long-term asset be

recorded?

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–10

Acquisition Cost of Property, Plant,

and Equipment

© Royalty Free PhotoDisc Collection/ Getty Images

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–11

What Are Expenditures?

(hwk E6)

Payments or obligations to make a future

payment for an asset or for a service

Capital

Expenditure

Expenditure for the

purchase or

expansion of a longterm asset

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Revenue

Expenditure

Expenditure for the

repair, maintenance,

and operation of a

long-term asset

9–12

Capital Expenditures

Outlays for plant assets, Betterments, which

are improvements to a

natural resources, and

plant asset but that do

intangible assets

not add to the plant’s

Additions, which are

physical layout

enlargements to the

Extraordinary

physical layout of a

repairs, which are

plant asset

repairs that

significantly enhance a

plant asset’s estimated

useful life or residual

value

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–13

Acquisition Costs

Includes all expenditures reasonable and necessary to

get an asset in place and ready for use

Installation costs

Freight

Insurance while in transit

Testing and setup

Are these items considered

acquisition costs?

Repair costs No

Interest charges on purchase No

© Royalty Free/ Corbis

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–14

Acquiring Land

Costs that should be debited to

the Land account include:

Sample

Acquisition of Land

Purchase price

Agent commissions

Legal fees

Accrued taxes paid by

purchaser

Grading

Land preparation fees

Assessments for local

improvements

Landscaping

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Net purchase price

Brokerage fees

Legal fees

Tearing down old building

Less salvage

Grading

Total cost

$340,000

12,000

4,000

$10,000

8,000

12,000

2,000

$370,000

Improvements to real estate like fences,

driveways, or parking lots have a limited

life. They should be recorded in an account

called Land Improvements, not the Land

account.

9–15

Acquiring Buildings

Acquisition costs include:

Purchase price

Repairs and other

expenditures required

to put it in usable

condition

Buildings are subject to

depreciation because they

have a limited useful life

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

© Royalty Free/ Corbis

9–16

Building Construction Costs

© Royalty Free/ Corbis

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Materials and labor

Overhead and other

indirect costs

Architects’ fees

Insurance during

construction

Interest on construction

loans

Lawyers’ fees

Building permits

Outside contractors

9–17

Leasehold Improvements

Improvements to leased property that become the property

of the lessor at the end of the lease

Classified as tangible assets

in the property, plant, and

equipment section of the

balance sheet

Costs of leasehold

improvements are

depreciated or amortized

over the remaining term of

the lease or the useful life of

the improvement, whichever

is shorter.

© Royalty Free/ Getty Images

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–18

Acquiring Equipment

• Acquisition costs include:

Purchase price (less cash discounts)

All expenditures connected with purchasing the

equipment and preparing it for use

•

•

•

•

•

•

Freight

Insurance in transit

Excise taxes and tariffs

Buying expenses

Installation costs

Cost of test runs

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Equipment is subject

to depreciation

because it has a

limited useful life

9–19

Group Purchases

(example SE 4 hwk E 8)

Land and other assets may sometimes be purchased

for a lump sum

Because buildings are

depreciable and land is not,

the purchase price must be

allocated to each asset

Land

Building

Totals

Appraisal

$ 20,000

180,000

$200,000

10 %

90

100 %

ABC Co. buys a building and

the land on which it is situated

for a lump sum of $170,000.

Assume that appraisals yield

estimates of $20,000 for the

land and $180,000 for the

building if purchased separately.

Allocate as follows:

Percentage

($20,000 ÷ $200,000)

($180,000 ÷ $200,000)

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Apportionment

$ 17,000 ($170,000 x 10%)

153,000 ($170,000 x 90%)

$170,000

9–20

What Is Depreciation?

The periodic allocation of the cost of a tangible

asset (other than land and natural resources)

over the asset’s estimated useful life

All tangible assets except land have a limited

useful life (physical deterioration and

obsolescence limit useful life)

Depreciation refers to the allocation of the cost

of a plant asset to the periods that benefit from

the asset, not to the asset’s physical deterioration

or decrease in market value

Depreciation is not a process of valuation; it is a

process of allocation

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–21

Four Factors That Affect the

Computation of Depreciation

1. Cost

Net purchase price of an asset plus all

reasonable and necessary expenditures

to get it in place and ready for use

2. Residual

value

The portion of an asset’s acquisition

cost that a company expects to recover

when it disposes of the asset

3. Depreciable

cost

4. Estimated

useful life

Cost less residual value

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Total number of service units expected

from a long-term asset

9–22

Accounting for Depreciation

Depreciation is recorded at the end of the

accounting period by an adjusting entry

Depreciation Expense, Asset Name

Accumulated Depreciation, Asset Name

To record depreciation for the period

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

xxx

xxx

9–23

Methods of Accounting for

Depreciation

Straight-line

method

Spreads the depreciable cost evenly

over the estimated useful life of the

asset

Production method

Based on the assumption that

depreciation is solely the result of use

and that passage of time plays no role

in the depreciation process

Accelerated method of depreciation

that results in larger amounts of

depreciation in earlier years of the

asset’s life and smaller amounts in

later years

Declining-balance

method

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–24

Straight-Line Method Illustrated

A delivery truck costs $20,000 and has an estimated

residual value of $2,000 at the end of its estimated

useful life of 5 years.

Yearly Depreciati on

Cost – Residual Value

Estimated Useful Life

$20,000 – $2,000

$3,600 per year

5 years

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–25

Depreciation Schedule,

Straight-Line Method

Date of purchase

End of first year

End of second year

End of third year

End of fourth year

End of fifth year

The amount of

depreciation is the

same each year

Cost

$20,000

20,000

20,000

20,000

20,000

20,000

Yearly

Depreciation

—

$3,600

3,600

3,600

3,600

3,600

Accumulated

depreciation

increases uniformly

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Accumulated

Depreciation

—

$3,600

7,200

10,800

14,400

18,000

Carrying

Value

$20,000

16,400

12,800

9,200

5,600

2,000

The carrying value

decreases uniformly until

it reaches the estimated

residual value

9–26

Production Method

A delivery truck costs $20,000 and has an estimated residual value of

$2,000 at the end of its estimated useful life of 90,000 miles. Assume the

truck was driven 20,000 miles during year 1; 30,000 miles during year 2;

10,000 miles during year 3; 20,000 miles during year 4; and 10,000 miles

during year 5.

Depreciati on Cost

Cost – Residual Value

Estimated Units of Useful Life

$20,000 – $2,000

$0.20 per mile

90,000 miles

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

The unit of output

or use should be

appropriate for

that asset

9–27

Depreciation Schedule,

Production Method

Date of purchase

End of first year

End of second year

End of third year

End of fourth year

End of fifth year

Cost

$20,000

20,000

20,000

20,000

20,000

20,000

There is a direct relation

between the amount of

depreciation each year

and the units of output

or use.

Miles

—

20,000

30,000

10,000

20,000

10,000

Yearly

Depreciation

—

$4,000

6,000

2,000

4,000

2,000

Accumulated

depreciation increases

each year in direct

relation to units of

output or use.

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Accumulated

Depreciation

—

$4,000

10,000

12,000

16,000

18,000

Carrying

Value

$20,000

16,000

10,000

8,000

4,000

2,000

The carrying value

decreases each year in

direct relation to units of

output or use until the

estimated residual value is

reached.

9–28

Declining-Balance Method

Based on the passage of time

Assumes that many kinds of

plant assets are most efficient

when new

Is consistent with the

matching rule

Any fixed rate can be used

Most common rate is twice

the straight-line depreciation

percentage (called doubledeclining-balance method)

© Royalty Free PhotoDisc Collection/ Getty Images

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–29

Double-Declining-Balance

Method Illustrated

A delivery truck costs $20,000 and has an estimated residual

value of $2,000. Its estimated useful life is 5 years.

Under the straight-line method, the depreciation rate for each

year is 20 percent:

100 percent 5 years 20 percent

Under the double-declining-balance method, the depreciation

rate for each year is 40 percent:

2 20 percent 40 percent

This fixed rate is applied to the remaining carrying value

at the end of each year.

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–30

Depreciation Schedule,

Double-Declining-Balance Method

Yearly Depreciation

Date of purchase

End of first year

End of second year

End of third year

End of fourth year

End of fifth year

Cost

$20,000

20,000

20,000

20,000

20,000

20,000

Note that the fixed

rate is always applied

to the carrying value

at the end of the

previous year.

(40% x $20,000)

(40% x $12,000)

(40% x $7,200)

(40% x $4,320)

Depreciation is

greatest in the first

year and declines

each year after that.

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

$8,000

4,800

2,880

1,728

592

Accumulated

Depreciation

—

$8,000

12,800

15,680

17,408

18,000

Carrying

Value

$20,000

12,000

7,200

4,320

2,592

2,000

The depreciation in the last

year is limited to the amount

necessary to reduce the

carrying value to the residual

value.

($2,592 - $2,000 = $592

9–31

Graphic Comparison of Three Methods

of Determining Depreciation

(examples SE 5-7 hwk E10 P4)

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–32

Group Depreciation

Companies often group

similar assets to

calculate depreciation

Group depreciation is

used in all fields of

industry and business

Average length of time

assets of the same type

are expected to last

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

© Royalty Free C Squared Studios/ Getty Images

9–33

Methods of Disposal

When plant

assets are no

longer

useful…

Discard

Sell for cash

Exchange for another asset

1. Record depreciation for the

partial year up to the date of

disposal

2. Remove the carrying value of

the asset

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–34

Discarded Plant Assets

Plant assets rarely last

as long as their

estimated lives

Never depreciate past

point at which carrying

value equals residual

value

Total accumulated

depreciation should

never exceed total

depreciable cost

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

© Royalty Free/ Corbis

9–35

Disposal of a Depreciable Asset

KOT Company purchased a machine on January 2, 2009, for $13,000 and

planned to depreciate it on a straight-line basis over its estimated useful life

(8 years). Its residual value at the end of 8 years is estimated to be $600.

On December 31, 2015, the balances of the relevant accounts were:

Machinery

Accumulated Depreciation, Machinery

13,000

9,300

On January 2, 2015, management disposed of the asset.

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–36

Disposal of a Plant Asset

Remove the carrying value of the asset

• Carrying value is computed by subtracting accumulated

depreciation from the acquisition cost of the asset

• If the asset is fully depreciated, the carrying value is zero

• If the asset is not fully depreciated, a loss is recorded

Jan. 2

Accumulated Depreciation, Machinery

Loss on Disposal of Machinery

Machinery

Discarded machine no longer

used in business

Machinery

13,000

Bal.

9,300

3,700

13,000

Accum. Depreciation, Machinery

13,000

-0-

9,300

9,300

Bal.

-0-

Gains and losses on disposal of plant assets

are classified as other revenues and expenses

on the income statement.

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–37

Selling a Plant Asset for Cash

In addition to removing the carrying value of the

asset, you will also record the cash received

© Royalty Free PhotoDisc Collection/ Getty Images

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

If cash received =

carrying value, no gain

or loss is recorded

If cash received <

carrying value, loss

is recorded

If cash received >

carrying value, gain

is recorded

9–38

Selling an Asset for Cash

Cash Received = Carrying Value

Received $3,700 cash for sale of machinery.

Remove the carrying value of the asset and record receipt of cash:

Jan. 2

Cash

Accumulated Depreciation, Machinery

Machinery

Sale of machinery for carrying

value; no gain or loss

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

3,700

9,700

13,00

9–39

Selling an Asset for Cash

Cash Received < Carrying Value

Received $2,000 cash for sale of machinery.

Remove the carrying value of the asset and record receipt of cash:

Jan. 2

Cash

2,000

Accumulated Depreciation, Machinery

9,300

Loss on Sale of Machinery

1,700

Machinery

Sale of machinery at less than carrying

value; loss of $1,700 recorded

($3,700 – $2,000)

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

13,000

9–40

Selling an Asset for Cash

Cash Received > Carrying Value

(example SE 8 hwk E 13)

Received $4,000 cash for sale of machinery.

Remove the carrying value of the asset and record receipt of cash:

Jan. 2

Cash

4,000

Accumulated Depreciation, Machinery

9,300

Gain on Sale of Machinery

Machinery

Sale of machinery at more than carrying

value; gain of $300 recorded

($4,000 – $3,700)

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

300

13,000

9–41

What Are Natural Resources?

Assets that are converted to inventory by

cutting, pumping, mining, or other extraction

methods

Timberlands

Oil and Gas Reserves

Mineral Deposits

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Record at acquisition

cost and show on the

balance sheet as

long-term assets

9–42

Depletion of Natural Resources

(1) The exhaustion of a natural resource and

(2) The proportional allocation of the cost of a

natural resource to the units extracted

Costs are allocated

much like the

production method

of depreciation

© Royalty-Free/Corbis

Cost of Natural Resource - Residual Value

Depletion Cost per Unit

Estimated Number of Units Available

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–43

Recording Depletion Expense

A mine that cost $3,600,000 has an estimated 3,000,000 tons of coal.

The estimated residual value of the mine is $600,000. During the first

year, 230,000 tons of coal are mined and sold.

Cost of Natural Resource - Residual Value

Depletion Cost per Unit

Estimated Number of Units Available

$3,600,000 - $600,000

$1 per ton

3,000,000 tons

Dec. 31

Depletion Expense, Coal Deposits

Accumulated Depletion, Coal Deposits

To record depletion of coal mine: $1

per ton, 230,000 tons mined and sold

230,000

230,000

Natural resources that have been extracted but not sold are considered inventory

and are not recorded as an expense until the year sold.

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–44

Depreciation of Closely Related

Plant Assets

(example SE 9 hwk E 15)

Closely related long-term assets are those assets

necessary to extract the resource

(Conveyors, drilling, and pumping devices)

If the life of the asset is

longer than the life of the

resource, depreciate on the

same basis as the depletion is

computed

If the life of the asset is

shorter than the life of the

resource, depreciate over the

shorter life of the asset

© Royalty Free C Squared Studios/ Getty Images

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–45

What Is an Intangible Asset?

Long-term, nonphysical

asset whose value comes

from the rights or

advantages afforded its

owner

Goodwill

Trademarks

Brand names

Copyrights

Patents

Leaseholds

Software

Customer lists

© Royalty Free C Squared Studios/ Getty Images

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–46

Importance of Intangibles

For some companies, intangible assets make up a

substantial portion of total assets

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–47

Accounting for Intangible Assets

Intangibles developed

by a firm for its own

benefit

Record as expense

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Intangibles acquired

from others

Record as asset; amortize

over the shorter of useful

life or legal life (not to

exceed 40 years)

9–48

Difficult Issues When

Accounting for Intangibles

How to account for the initial carrying value?

How to account for that amount under normal

business conditions (periodic write-off or

amortization)?

How to account for the amount if the value

declines substantially and permanently?

How to estimate an intangible asset’s value

and useful life?

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–49

Intangible Assets Illustrated

Later Bottling Company purchases a patent on a unique bottle cap for

$36,000. The patent will last for 20 years, but the product using the cap

will be sold only for the next six years.

Record the purchase of the patent:

Patents

36,000

Cash

36,000

To record purchase of bottle cap

patent

Record the annual amortization expense:

Amortization Expense

Patents

To record amortization expense for

patent ($36,000 ÷ 6 years)

6,000

6,000

Notice that the Patents account is directly reduced by the amount of amortization

expense, whereas depreciation or depletion is accumulated in separate contra

accounts for other long-term assets.

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–50

Intangible Assets Illustrated

(hwk E 17)

The patent becomes worthless after only 1 year. Record the write-off:

Loss on Patent

Patents

30,000

30,000

To record the write-off of a

worthless patent

($36,000 – $6,000)

If the patent becomes worthless

before it is fully amortized, the

remaining carrying value is

written off as a loss by

removing it from the Patents

account.

© Royalty Free C Squared Studios/ Getty Images

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–51

Research and Development Costs

The FASB requires that all R&D costs be treated as

revenue expenditures and charged to expense in the

period in which they are incurred.

Why?

Too difficult to trace specific costs to specific profitable

developments

Costs of research and development are continuous and

necessary for the success of a business and so should be

treated as current expenses

Studies show that 30 to 90 percent of all new product fail

and 75 percent of new-product expenses go to unsuccessful

products

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–52

Computer Software Costs

Costs incurred in developing

computer software for sale or

lease or for a firm’s internal use

are research and development Once a working program is

costs until the product has

ready, all costs are recorded

proved technologically feasible as assets

Costs incurred before

technologically feasible

should be charged to expense

as incurred

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Amortize over the

estimated economic life

using the straight-line

method

9–53

Goodwill

A company’s good reputation

Customer satisfaction

Good management

Manufacturing efficiency

Good location

© Royalty Free/ Corbis

Goodwill exists when a purchaser pays more for a business

than the fair market value of the business’s net assets

Goodwill should not be recorded unless it is paid for in connection with

the purchase of a whole business

Goodwill = Purchase price – FMV of identifiable net assets

Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

9–54