The American Journey: Ch. 10: The Age of Jackson

advertisement

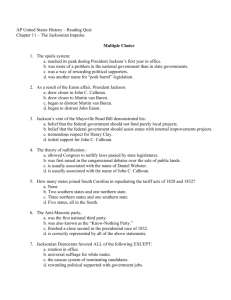

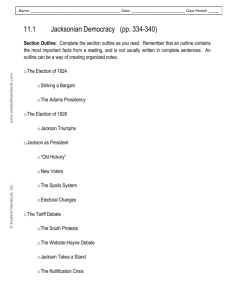

Section 1: Jacksonian Democracy The election of 1824 featured three favorite sons, candidates supported by their home states rather than a national party. Henry Clay of Kentucky Andrew Jackson of Tennessee John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts (son of John Adams) Jackson won the most popular votes, but no one received a majority, over 50%. Jackson did receive the plurality, the largest single share (99 of 162). The Twelfth Amendment says that when no candidate receives a majority, the House of Representatives selects the president. Adams and Clay made a secret deal. Clay used his influence as Speaker of the House to persuade the House not to vote for Jackson. Adams was elected, and he named Clay as secretary of state. But this “corrupt bargain,” along with unpopular policies (stronger navy, larger government) made John Quincy Adams a very unpopular president. By Democratic-Republicans supported Jackson and supported states’ rights and smaller government. 1828, there were two parties. They were generally frontier people, immigrants, and city workers. National Republicans supported Adams and supported stronger government, a national bank, and road-building. They were generally farmers and merchants. This campaign featured an extreme amount of mudslinging, attempts to ruin the other candidate’s reputation. This was also the first use of slogans, buttons, and rallies, all of which became permanent parts of campaigning. Jackson ended up winning in a landslide, an overwhelming victory. 56% of the vote, 178 electoral votes John C. Calhoun switched parties to become Jackson’s vice president (he was Adams’s V.P.). Jackson was immensely popular, especially with small farmers and craftsmen. He seemed like “a man of the people.” He was a patriot. He was a war hero. He worked hard from poverty to wealth. Jackson had gained his popularity during the War of 1812. He defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend and the British at the Battle of New Orleans. His troops called him “Old Hickory” because he was as tough as a hard hickory tree. Jackson promised “equal protection and equal benefits” for all Americans. (This actually meant all white males.) Still, the property requirements to vote began to loosen, and many white males finally got to vote. Democrats favored democracy, and they sought to break up the bureaucracy, a system in which nonelected officials carried out laws. Jackson replaced many nonelected officials with his supporters. Some accused Jackson of acting as a tyrant. Jackson and his supporters responded that “to the victors belong the spoils.” In other words, since Jackson won, he and his supporters earned the right to the benefits. The process of replacing government employees with the winning candidate’s supporters is called the spoils system. Another change was the abandoning of the caucus system. Under the caucus system, political candidates were chosen by special committees of Congress. Under Jackson, nominating conventions of state delegates replaced the Congressional committees. In 1828, Congress placed a tariff, a fee on imported goods, on all goods from Europe. This encouraged Americans to buy American. The North loved the tariff—it caused people to buy their goods. The South hated it—the South had little manufacturing, and it meant higher prices. Vice President John C. Calhoun argued that the South had the right to nullify (cancel) a federal law states disagreed with. Some Southerners called for the South to secede. Do states have the right to secede if they disagree with the federal government? Calhoun said it this way: Either the states decide what’s constitutional, or the Supreme Court and Congress will always tell states what to do. He argued that since the federal government was a creation of the states, states can break away. Senator Daniel Webster loudly declared that nullification and secession were appalling. In 1830 Jackson finally made his view known: he declared the Union must be preserved. In 1832 Calhoun won election to Senate and resigned as Jackson’s vice president. Eventually John C. Calhoun and South Carolina became President Jackson’s biggest enemies. In 1832, Jackson and Congress passed a new, lower tariff to appease the South. But the South Carolina legislature passed the Nullification Act, refusing to pay the “illegal” tariffs of 1828 and 1832 and threatening secession. Eventually Henry Clay and President Jackson struck a deal for a lower tariff with S.C. Calhoun and S.C. claimed victory, saying they’d forced a revision of the tariff, but they also realized a state couldn’t secede without a fight. Section 2: The Removal of Native Americans The Native Americans of Georgia faced a large problem when white settlers began to move onto their land. Many wanted the tribes moved west of the Mississippi River to free up the good Southern soil for white farmers. Jackson supported the calls for relocation. In 1830, Congress OK’d the Indian Removal Act. Congress paid Indians to move west. In 1834 Congress created the Indian Territory in modern-day Oklahoma. The Cherokee Nation refused to move. In the 1790’s the federal government had recognized the Cherokee people as a separate nation with its own laws. But Georgia refused to acknowledge them. The Cherokee sued Georgia (Worcester v. Georgia), a Supreme Court case in which Chief Justice John Marshall sided with the Cherokee. But Jackson overstepped the Supreme Court. “John Marshall has made his decision. Now let him enforce it.” In 1835, the federal government persuaded a few Cherokee to sign over their land. But most Cherokee refused and petitioned the government for understanding. Jackson and the federal government were not persuaded. In 1838, federal troops under Gen. Winfield Scott removed the Cherokee. The Cherokee did not fight back, and thousands died on their forced march west through bad weather. “The Trail of Tears” Some Black Hawk, a Sauk chief, led a force to recapture their homeland in Illinois. Natives did resist, however. Hundreds were killed, others pursued and slaughtered. The Seminole people, led by Chief Osceola, teamed up with former slaves to attack white settlers in Florida. They used guerilla tactics, ambushes and surprise attacks and retreats. In 1835, they killed most of a force of 110 under Major Francis Dade and outlasted the troops. The Seminole were the only Native tribe to successfully resist removal In the end, few Natives remained east of the Mississippi. They had given up over 100 million acres and received 32 million acres and $68 million in return. The “Five Civilized Tribes” were relocated to present-day Oklahoma. Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, Chickasaw & Choctaw Section 3: Jackson and the Bank President Jackson had long hated the Bank of the United States. It was chartered by Congress, but run by wealthy Eastern bankers instead of elected officials. In 1832, Senators Daniel Webster and Henry Clay asked the president of the Bank, Nicholas Biddle, to help them defeat Jackson’s reelection. The Bank’s charter was to be renewed in 1836, but Clay and Webster asked Biddle to apply for a new charter in 1832. They thought the Bank was popular. If Jackson rejected the Bank charter, he’d be defeated, they figured, and Clay would be elected. Jackson was sick in bed when the charter came to him. He told his friend Martin Van Buren, “The bank…is trying to kill me. But I will kill it!” He vetoed (rejected) the charter. McCulloch v. Maryland had declared that the Bank was constitutional. But Jackson once again fought the Supreme Court. Clay and Webster’s plan backfired. Most people supported Jackson’s veto, and he was reelected in another landslide. Martin Van Buren was elected vice president. Reelected, Jackson tried again to kill the bank. He ordered all government deposits withdrawn from the Bank and placed in smaller state banks. Jackson won his battle—the Bank was dead without government deposits. However, the death of the National Bank led to economic problems later. Cartoon, pg. 460 Jackson did not run a third time, but his vice president, Martin Van Buren, easily won in 1836. His opposition was the Whig Party, a new party of anti-Jacksonians and former National Republicans. In 1837, the country fell into a deep depression, a period of low employment and poor business. “The Panic of 1837”: Land values dropped sharply, investments declined, and banks failed. What is a “bubble”? Almost immediately, businesses failed and many Americans lost their jobs. People were terribly poor and angry. Although Van Buren was a laissez-faire president, he did persuade Congress to create a federal treasury in 1840 to combat the depression. What’s laissez-faire? Government should interfere as little as possible. Unlike Jackson, Van Buren believed the government’s money had to be kept somewhere outside private banks to guard against bank crises. But Van Buren’s own party (Democratic) and many Whigs disagreed with him, and a split formed in the Democratic party. This gave the Whigs a chance to come to power. The Whigs’ candidate, William Henry Harrison, was popular from the Battle of Tippecanoe in the War of 1812. His running mate was John Tyler. “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too!” Harrison was also portrayed as “a man of the people,” just like Jackson. He supported small farmers and common people, just like Jackson. Whigs generally supported a stronger federal government. Whaaa?! Harrison won, but he died four weeks after his inauguration. He gave his 1½-hour inauguration speech in a blizzard and later died of pneumonia. D’oh! John Tyler became the nation’s first vice president to gain presidential office after a president’s death. But Tyler backed mostly Democratic ideas, and the Whig party abandoned him. Four years later, the Whig party was in disarray. Democratic candidate James K. Polk won in 1844. The Whig Party was out of power after only four years.