apportionment, election methods, and districting

advertisement

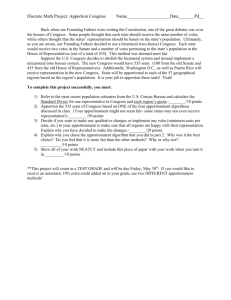

APPORTIONMENT, ELECTION METHODS, AND DISTRICTING Topic #21 The Legislative Compromise • Recall the Legislative [or Connecticut] Compromise pertaining to the representative character of Congress. • Congress is bicameral with: • two coequal houses with substantially equal powers; and • in particular, legislation requires the support of a concurrent majority in both houses. – In the House of Representatives, states have representation (approximately) proportional to population. • Members serve two-year terms. – In the Senate, states are equally represented. • • • • The size of the Senate = 2 x S, where S is the number of states. Senators serve staggered six-year terms. Senate “districts” coincide with states. Since ratification of the 17th Amendment, Senators have been popularly elected, in the same manner as Representatives. The Apportionment of House Seats • The [original] Apportionment Clause: – Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons. – The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. – The Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Representative. – The Constitution does not fix the size of the House. – The Constitution prescribed a provisional apportionment of 65 House seats. Apportionment of House Seats (cont.) • Note that apportionment is based on the total population of each state, not on – the number of legal residents, – the number of citizens, – the size of the voting age population, – the number of eligible, registered, or participating voters. – Some technical questions remain, e.g., • out-of-state college students, • personnel stationed at military bases, • prisoners, etc. Apportionment of House Seats (cont.) • The first Congress had to pass legislation to – create a Census Bureau to conduct an initial census that would establish the “actual enumeration” of state populations; – fix the size of the House [at 105], and – apportion these seats among the states “according to their respective numbers.” • The Constitution does not specify a mathematical formula for this apportionment. – It was quickly discovered that the mathematical problem of apportionment has no straightforward solution. • The basic problem is that [for House seats as opposed to “direct taxes”] the answer must be in relative small whole numbers: – how to “cure the mischief of fractions”? – Two rival apportionment formulas were proposed. • (Secretary of Treasury) Alexander Hamilton’s Method of Largest Remainders. • (Secretary of State) Thomas Jefferson’s Method of Greatest Divisors. • The two methods produced different apportionments of 105 House seats. Apportionment of House Seats (cont.) • The apportionment bill of 1790: – Congress passed a bill that apportioned 105 House seats on the basis of Hamilton’s method. – Following Jefferson’s advice, President Washington vetoed the bill [the first Presidential veto in history]. – Congress then passed another apportionment bill using Jefferson’s method, which the President signed. • Throughout the 19th Century, Congress passed a new apportionment law every decade. – Each bill increased the size of the House, • typically so that no state would lose House seats. – Bills in different decades used different apportionment formulas. – The process was quite political, often partisan, and inconsistent. – By the early 20th Century, the House size exceeded 400. Apportionment of House Seats (cont.) • With the admission of Arizona and New Mexico into the union in 1912, Congress froze the House size at 435. – The size was temporarily expanded to 437 to give temporary representation to Alaska and Hawaii in the late 1950s. • In 1940, Congress permanently adopted the Method of Equal Proportions for apportioning the 435 seats. • Since then, the apportionment process has been on “automatic pilot,” in that Congress does not pass a new apportionment bill every decade. • Last Spring the Census Bureau tried to get an accurate count of the population of each state as of April 1, 2010. • In April 2011, the Census Bureau will announce – the official apportionment population of each state (based on the 2010 census), and – the number of House seats each state will have for the coming decade (based on the Method of Equal Proportions). The 1990 and 2000 Apportionments Also see K&J, p. 192 Regional Shift in House Seats: 1900-2000 (%) The Election of Representatives • Article I, Section 4. The times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by law make or alter such regulations, except as to the places of choosing Senators. • Congress has used its power to establish a nationally uniform day for electing Senators and Representatives [and also Presidential electors]. • Typically states have prescribed election of their House members from single-member districts. – Since 1968 (and in various earlier periods), Congress has required states to use SMDs for electing Representatives. The Election of Representatives • A variety of election methods might be used in SMDs: – Simple Plurality: vote for one candidate; the candidate with the most votes wins. – Plurality Plus Runoff: vote for one candidate; if the candidate with the most votes is supported by a majority of votes, that candidate is elected; otherwise, there is runoff (second election) between the top two candidates. – Instant Runoff Voting: rank the candidates by order of preference; if a candidate is supported by a majority of first preference ballots, that candidate is elected; otherwise, the candidate with the fewest first preference is eliminated and his/her votes are transferred on the basis of second preferences; if a candidate is now supported by a majority of first preference and transferred ballots, that candidate is elected; otherwise, continue in like manner until a candidate is supported by a majority of first preference and transferred ballots. – Approval Voting: vote for any number of candidates; the candidate with the most votes is elected. – Note: with multimember districts [MMDs], a wider variety of election methods is available, including many variants of proportional representation. The Election of Representatives (cont.) • Even when allowed a choice by Congress, states have almost always chosen to use the Simple Plurality method. • Any SMD method requires that each state with more than one House seat be divided into districts equal in number to its apportionment of House seats. – This process is variously called: • (re)districting, • (re)apportionment [which tends to confuse the creation of districts within states with the allocation of seats among states], and • gerrymandering [a somewhat derogatory term]. – We shall use the [neutral] term districting. • These districts are called Congressional Districts (CDs). – Members of state legislatures are similarly election from districts, though not always SMDs. Congressional Districting • State legislatures determine how Congressional District boundaries are drawn following each census. – Usually, districting is done by the legislature itself. • State legislatures typically also draw their own district boundaries. • The districting process is highly contested and political and often partisan. • State legislative elections take on special importance every 10 years. – A few states set up special (more or less politically neutral) commissions to draw district boundaries. – Sometimes legal actions are initiated, with the result that courts in effect draw district boundaries. Congressional Districting (cont.) • Legislative districting raises two questions: – malapportionment, pertaining to the size (population) of the districts, and – gerrymandering, pertaining to the geographical shape of the districts. • District size: – If districts with (perhaps highly) unequal populations each elect one representative (with one vote in the legislature), the voting power of individual voters varies from district to district. – Note that the U.S. Senate is highly malapportioned in this sense. Malapportionment • Prior to the 1960s, many states had malapportioned Congressional districts. – State legislative districts were often malapportioned in even greater degree. – State legislatures were often dominated by rural representatives who resisted redrawing district boundaries to reflect the growth of urban and suburban areas. – State legislatures were inclined to preserve existing CDs if their apportionment of House seats did not change, • even though there may have been large population shifts within the states. Malapportionment (cont.) • Does malapportionment of Congressional Districts violate the Equal Protect Clause of the 14th Amendment? – Colgrove v. Green (1946): exercising judicial self-restraint, the Supreme Court declared districting to be a nonjusticiable “political question.” – Baker v. Carr (1963): a more activist court overruled the Colgrove v. Green precedent and declared districting to be justiciable. – Reynolds v. Simms (1964): the courts ruled that malapportionment does violate the Equal Protection Clause, which demands “one man, one vote” (i.e., districts with equal populations). – Wesberry v. Sanders (1964): the Court applied “one man, one vote” specifically to Congressional Districts. Malapportionment (cont.) • Since the mid-1960, all Congressional (and other) districts within a state have been required to be almost precisely equal in population (not number of voters) at the beginning of each census decade. – Thus all states with more than one CD must redraw CDs boundaries each decade, even if (like Maryland for the past six decades) they have neither gained nor lost seats. – In 2004, Texas and Georgia redrew CDs boundaries (for partisan political reasons) when they were not required to. District Boundaries: Gerrymandering • Gerrymandering: drawing district boundaries (often creating weird shapes) in order to advance one or other political interest. – Political scientists differ on whether gerrymandering can be wholly avoided, i.e., • whether neutral non-political districting criteria can be identified. • Gerrymandering has become more pronounced in recent decades. – The “one man, one vote” rule means that jurisdictional (and other) boundaries cannot be followed. – Technological developments: • especially computerized census, voter registration, and election data and other geographical information systems, • sophisticated computer software for districting. The Original “Gerrymander” Some Recent Gerrymanders Closer to Home Hypothetical Districting Example Gerrymandering (cont.) • Different types of gerrymanders: – Partisan gerrymandering: draw district boundaries to maximize the number of seats likely to be controlled by one’s own party, achieving this by “cracking and packing” the other party’s areas of support, i.e., • crack apart areas of support for the other party, and/or • pack supporters of the other party into as few districts as possible • [see Mixed Districts diagram]. – Bipartisan gerrymandering: draw district boundaries to create many safe districts for both parties [Homogeneous Districts diagram]. – Non-partisan gerrymandering: draw district boundaries to protect incumbents (of both parties), so they can acquire valuable legislative seniority. – Racial/ethnic gerrymandering: draw district boundaries to maximize (or minimize) the number of minority (e.g., African-American, Hispanic, etc.) members likely to be elected. • Voting Rights Act and “majority minority” districts • Shaw v. Reno (1993)