Recent Statistical Approaches

advertisement

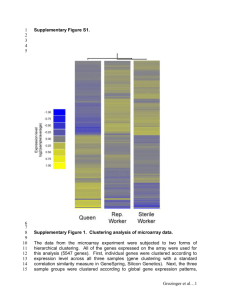

Classification of Microarray Data

- Recent Statistical Approaches

Geoff McLachlan and Liat Ben-Tovim Jones

Department of Mathematics & Institute for Molecular Bioscience

University of Queensland

Tutorial for the APBC January 2005

Institute for Molecular Bioscience,

University of Queensland

Outline of Tutorial

• Introduction to Microarray Technology

• Detecting Differentially Expressed Genes in Known Classes

of Tissue Samples

• Cluster Analysis: Clustering Genes and Clustering Tissues

• Supervised Classification of Tissue Samples

• Linking Microarray Data with Survival Analysis

Outline of Tutorial

• Introduction to Microarray Technology

• Detecting Differentially Expressed Genes in Known Classes

of Tissue Samples

BREAK

• Cluster Analysis: Clustering Genes and Clustering Tissues

• Supervised Classification of Tissue Samples

• Linking Microarray Data with Survival Analysis

Outline of Tutorial

• Introduction to Microarray Technology

• Detecting Differentially Expressed Genes in Known Classes

of Tissue Samples

• Cluster Analysis: Clustering Genes and Clustering Tissues

• Supervised Classification of Tissue Samples

• Linking Microarray Data with Survival Analysis

“Large-scale gene expression studies are not

a passing fashion, but are instead one aspect

of new work of biological experimentation,

one involving large-scale, high throughput

assays.”

Speed et al., 2002, Statistical Analysis of Gene

Expression Microarray Data, Chapman and

Hall/ CRC

Growth of microarray and microarray methodology literature listed in PubMed from 1995 to

2003.

The category ‘all microarray papers’ includes those found by searching PubMed for

microarray* OR ‘gene expression profiling’. The category ‘statistical microarray papers’

includes those found by searching PubMed for ‘statistical method*’ OR ‘statistical

techniq*’ OR ‘statistical approach*’ AND microarray* OR ‘gene expression profiling’.

A microarray is a new technology which allows the

measurement of the expression levels of thousands of genes

simultaneously.

(1) sequencing of the genome (human, mouse, and others)

(2) improvement in technology to generate high-density

arrays on chips (glass slides or nylon membrane).

The entire genome of an organism can be probed

at a single point in time.

(1) mRNA Levels Indirectly Measure Gene Activity

Every cell contains

the same DNA.

Cells differ in the

DNA (gene) which

is active at any one

time.

Genes code for

proteins through the

intermediary of

mRNA.

The activity of a

gene (expression)

can be determined

by the presence of

its complementary

mRNA.

Target and Probe DNA

Probe DNA

- known

Sample (target)

- unknown

(2) Microarrays Indirectly Measure Levels of mRNA

•mRNA is extracted from the cell

•mRNA is reverse transcribed to cDNA (mRNA itself is unstable)

•cDNA is labeled with fluorescent dye TARGET

•The sample is hybridized to known DNA sequences on the array

(tens of thousands of genes) PROBE

•If present, complementary target binds to probe DNA

(complementary base pairing)

•Target bound to probe DNA fluoresces

Spotted cDNA Microarray

Compare the gene expression levels for two cell

populations on a single microarray.

Microarray Image

Red: High expression in target labelled with cyanine 5 dye

Green : High expression in target labelled with cyanine 3 dye

Yellow : Similar expression in both target samples

Assumptions:

Gene Expression

cellular mRNA levels directly

reflect gene expression

(1)

mRNA

(2)

intensity of bound target is a

measure of the abundance of the

mRNA in the sample.

Fluorescence Intensity

Experimental Error

Sample contamination

Poor quality/insufficient mRNA

Reverse transcription bias

Fluorescent labeling bias

Hybridization bias

Cross-linking of DNA (double strands)

Poor probe design (cross-hybridization)

Defective chips (scratches, degradation)

Background from non-specific hybridization

The Microarray Technologies

Spotted Microarray

Affymetrix GeneChip

cDNAs, clones, or short and long

oligonucleotides deposited onto

glass slides

short oligonucleotides synthesized in situ

onto glass wafers

Each gene (or EST) represented

by its purified PCR product

Each gene represented multiply - using

16-20 (preferably non-overlapping)

25-mers.

Simultaneous analysis of two

samples (treated vs untreated cells)

provides internal control.

Each oligonucleotide has single-base

mismatch partner for internal control of

hybridization specifity.

relative gene expressions

absolute gene expressions

Each with its own advantages and disadvantages

Pros and Cons of the Technologies

Spotted Microarray

Affymetrix GeneChip

Flexible and cheaper

More expensive yet less flexible

Allows study of genes not yet sequenced Good for whole genome expression

(spotted ESTs can be used to discover

analysis where genome of that organism

new genes and their functions)

has been sequenced

Variability in spot quality from slide to

slide

High quality with little variability between

slides

Provide information only on relative

gene expressions between cells or tissue

samples

Gives a measure of absolute expression

of genes

Aims of a Microarray Experiment

• observe changes in a gene in response to external stimuli

(cell samples exposed to hormones, drugs, toxins)

• compare gene expressions between different tissue types

(tumour vs normal cell samples)

To gain understanding of

• function of unknown genes

• disease process at the molecular level

Ultimately to use as tools in Clinical Medicine for diagnosis,

prognosis and therapeutic management.

Importance of Experimental Design

• Good DNA microarray experiments should have clear

objectives.

• not performed as “aimless data mining in search of

unanticipated patterns that will provide answers to unasked

questions”

(Richard Simon, BioTechniques 34:S16-S21, 2003)

Replicates

Technical replicates: arrays that have been hybridized to the same

biological source (using the same treatment, protocols, etc.)

Biological replicates: arrays that have been hybridized to different

biological sources, but with the same preparation, treatments, etc.

Extracting Data from the Microarray

•Cleaning

Image processing

Filtering

Missing value estimation

•Normalization

Remove sources of systematic variation.

Sample 1

Sample 2

Sample 3

Sample 4 etc…

Gene Expressions from Measured Intensities

Spotted Microarray:

log 2(Intensity Cy5 / Intensity Cy3)

Affymetrix:

(Perfect Match Intensity – Mismatch Intensity)

Data Transformation

log x c x

2

2

Rocke and Durbin (2001), Munson (2001), Durbin et al. (2002),

and Huber et al. (2002)

Representation of Data from M Microarray Experiments

Sample 1 Sample 2

Expression Signature

Gene 1

Gene 2

Expression Profile

Gene N

Sample M

Assume we have

extracted gene

expressions values

from intensities.

Gene expressions

can be shown as

Heat Maps

Microarrays present new problems for statistics because

the data is very high dimensional with very little

replication.

Gene Expression Data represented as N x M Matrix

Sample 1 Sample 2

Expression Signature

Gene 1

Gene 2

Expression Profile

Gene N

Sample M

N rows correspond to the

N genes.

M columns correspond to the

M samples (microarray

experiments).

Microarray Data Notation

Represent the N x M matrix A:

A = (y1, ... , yM)

Classifying Tissues on Gene Expressions

the feature vector yj contains the expression levels on the N genes

in the jth experiment (j = 1, ... , M). yj is the expression signature.

AT = (y1, ... , yN)

Classifying Genes on the Tissues

the feature vector yj contains the expression levels on the M tissues

on the jth gene (j = 1, ... , N). yj is the expression profile.

In the N x M matrix A:

N = No. of genes (103-104)

M = No. of tissues (10-102)

Classification of Tissues on Gene Expressions:

Standard statistical methodology appropriate

when M >> N,

BUT here

N >> M

Classification of Genes on the Basis of the Tissues:

Falls in standard framework, BUT not all the

genes are independently distributed.

Mehta et al (Nature Genetics, Sept. 2004):

“The field of expression data analysis is particularly

active with novel analysis strategies and tools being

published weekly”, and the value of many of these

methods is questionable. Some results produced by using

these methods are so anomalous that a breed of ‘forensic’

statisticians (Ambroise and McLachlan, 2002; Baggerly et

al., 2003) who doggedly detect and correct other HDB

(high-dimensional biology) investigators’ prominent

mistakes, has been created.

Outline of Tutorial

•Introduction to Microarray Technology

•Detecting Differentially Expressed Genes in Known Classes

of Tissue Samples

•Cluster Analysis: Clustering Genes and Clustering Tissues

•Supervised Classification of Tissue Samples

•Linking Microarray Data with Survival Analysis

Gene 1

Gene 2

.

.

.

.

Gene N

Sample 2

.

.

.

.

Sample 1

Sample M

Sample 2

.

.

.

.

Sample 1

Gene 1

Gene 2

.

.

.

.

Gene N

Class 1

Class 2

Sample M

Fold Change is the Simplest Method

Calculate the log ratio between the two classes

and consider all genes that differ by more than

an arbitrary cutoff value to be differentially

expressed. A two-fold difference is often

chosen.

Fold change is not a statistical test.

Multiplicity Problem

Perform a test for each gene to determine the statistical significance

of differential expression for that gene.

Problem: When many hypotheses are tested, the probability of a

type I error (false positive) increases sharply with the number of

hypotheses.

Further complicated by gene co-regulation and subsequent

correlation between the test statistics.

Example:

Suppose we measure the expression of 10,000 genes

in a microarray experiment.

If all 10,000 genes were not differentially expressed,

then we would expect for:

P= 0.05

for each test, 500 false positives.

P= 0.05/10,000 for each test, .05 false positives.

Methods for dealing with the Multiplicity Problem

•The Bonferroni Method

controls the family wise error rate (FWER).

(FWER is the probability that at least one false positive

error will be made.) - but this method is very

conservative, as it tries to make it unlikely that even

one false rejection is made.

•The False Discovery Rate (FDR)

emphasizes the proportion of false positives among the

identified differentially expressed genes.

Test of a Single Hypothesis

The M tissue samples are classified with respect to g classes on

the basis of the N gene expressions.

Assume that there are ni tissue samples from each class

Ci (i = 1, …, g), where

M = n1 + … + ng.

Take a simple case where g = 2.

The aim is to detect whether some of the thousands of genes

have different expression levels in class C1 than in class C2.

Test of a Single Hypothesis (cont.)

For gene j, let Hj denote the null hypothesis of no association

between its expression level and membership of the class, where

(j = 1, …, N).

Hj = 0

Hj = 1

Null hypothesis for the jth gene holds.

Null hypothesis for the jth gene does not hold.

Retain Null

Hj = 0

Hj = 1

Reject Null

type I error

type II error

Two-Sample t-Statistic

Student’s t-statistic:

Tj

y1 j y 2 j

2

1j

s

n1 s

2

2j

n2

Two-Sample t-Statistic

Pooled form of the Student’s t-statistic, assumed common

variance in the two classes:

Tj

y1 j y 2 j

sj 1 n1 1 n2

Two-Sample t-Statistic

Modified t-statistic of Tusher et al. (2001):

Tj

y1 j y 2 j

sj 1 n1 1 n2 a0

Multiple Hypothesis Testing

Consider measures of error for multiple hypotheses.

Focus on the rate of false positives with respect to the

number of rejected hypotheses, Nr.

Possible Outcomes for N Hypothesis Tests

Accept Null

Reject Null

Total

Null True

N00

N01

N0

Non-True

N10

N11

N1

Total

N - Nr

Nr

N

Possible Outcomes for N Hypothesis Tests

Accept Null

Reject Null

Total

Null True

N00

N01

N0

Non-True

N10

N11

N1

Total

N - Nr

Nr

N

FWER is the probability of getting one or more

false positives out of all the hypotheses tested:

FWER pr{N 01 1}

Bonferroni method for controlling the FWER

Consider N hypothesis tests:

H0j versus H1j,

j = 1, … , N

and let P1, … , PN denote the N P-values for these tests.

The Bonferroni Method:

Given P-values P1, … , PN reject null hypothesis H0j if

Pj < a / N .

False Discovery Rate (FDR)

# (false positives)

FDR

# (rejected hypotheses )

The FDR is essentially the expectation of the

proportion of false positives among the identified

differentially expressed genes.

Possible Outcomes for N Hypothesis Tests

Accept Null

Reject Null

Total

Null True

N00

N01

N0

Non-True

N10

N11

N1

Total

N - Nr

Nr

N

N 01

FDR

Nr

Controlling FDR

Benjamini and Hochberg (1995)

Key papers on controlling the FDR

• Genovese and Wasserman (2002)

• Storey (2002, 2003)

• Storey and Tibshirani (2003a, 2003b)

• Storey, Taylor and Siegmund (2004)

• Black (2004)

• Cox and Wong (2004)

Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) Procedure

Controls the FDR at level a when the P-values following

the null distribution are independent and uniformly distributed.

(1) Let

p(1) p( N )

(2) Calculate

be the observed P-values.

kˆ arg max k : p(k ) ak / N .

1 k N

(3) If

k̂

exists then reject null hypotheses corresponding to

p(1) p( k ) . Otherwise, reject nothing.

Example: Bonferroni and BH Tests

Suppose that 10 independent hypothesis tests are carried out

leading to the following ordered P-values:

0.00017 0.00448 0.00671 0.00907 0.01220

0.33626 0.39341 0.53882 0.58125 0.98617

(a) With a = 0.05, the Bonferroni test rejects any hypothesis

whose P-value is less than a / 10 = 0.005.

Thus only the first two hypotheses are rejected.

(b) For the BH test, we find the largest k such that P(k) < ka / m.

Here k = 5, thus we reject the first five hypotheses.

SHORT BREAK

Null Distribution of the Test Statistic

Permutation Method

The null distribution has a resolution on the order of the

number of permutations.

If we perform B permutations, then the P-value will be estimated

with a resolution of 1/B.

If we assume that each gene has the same null distribution and

combine the permutations, then the resolution will be 1/(NB)

for the pooled null distribution.

Using just the B permutations of the class labels for the

gene-specific statistic Tj , the P-value for Tj = tj is assessed as:

where t(b)0j is the null version of tj after the bth permutation

of the class labels.

If we pool over all N genes, then:

Null Distribution of the Test Statistic: Example

Class 1

Gene 1

Gene 2

A1(1) A2(1) A3(1)

A1(2) A2(2) A3(2)

Class 2

B4(1) B5(1) B6(1)

B4(2) B5(2) B6(2)

Suppose we have two classes of tissue samples, with three samples

from each class. Consider the expressions of two genes, Gene 1 and

Gene 2.

Class 1

Gene 1

Gene 2

A1(1) A2(1) A3(1)

A1(2) A2(2) A3(2)

Class 2

B4(1) B5(1) B6(1)

B4(2) B5(2) B6(2)

To find the null distribution of the test statistic for Gene 1, we

proceed under the assumption that there is no difference between the

classes (for Gene 1) so that:

Gene 1

A1(1) A2(1) A3(1)

A4(1) A5(1) A6(1)

And permute the class labels:

Perm. 1 A1(1) A2(1) A4(1)

...

There are 10 distinct permutations.

A3(1) A5(1) A6(1)

Ten Permutations of Gene 1

A1(1) A2(1) A3(1)

A4(1) A5(1) A6(1)

A1(1) A2(1) A4(1)

A3(1) A5(1) A6(1)

A1(1) A2(1) A5(1)

A3(1) A4(1) A6(1)

A1(1) A2(1) A6(1)

A3(1) A4(1) A5(1)

A1(1) A3(1) A4(1)

A2(1) A5(1) A6(1)

A1(1) A3(1) A5(1)

A2(1) A4(1) A6(1)

A1(1) A3(1) A6(1)

A2(1) A4(1) A5(1)

A1(1) A4(1) A5(1)

A2(1) A3(1) A6(1)

A1(1) A4(1) A6(1)

A2(1) A3(1) A5(1)

A1(1) A5(1) A6(1)

A2(1) A3(1) A4(1)

As there are only 10 distinct permutations here, the

null distribution based on these permutations is too

granular.

Hence consideration is given to permuting the labels

of each of the other genes and estimating the null

distribution of a gene based on the pooled permutations

so obtained.

But there is a problem with this method in that the

null values of the test statistic for each gene does not

necessarily have the theoretical null distribution that

we are trying to estimate.

Suppose we were to use Gene 2 also to estimate

the null distribution of Gene 1.

Suppose that Gene 2 is differentially expressed,

then the null values of the test statistic for Gene 2

will have a mixed distribution.

Class 1

Class 2

Gene 1

Gene 2

A1(1) A2(1) A3(1)

A1(2) A2(2) A3(2)

B4(1) B5(1) B6(1)

B4(2) B5(2) B6(2)

Gene 2

A1(2) A2(2) A3(2)

B4(2) B5(2) B6(2)

Permute the class labels:

Perm. 1 A1(2) A2(2) B4(2)

...

A3(2) B5(2) B6(2)

Example of a null case: with 7 N(0,1) points and

8 N(0,1) points; histogram of the pooled two-sample

t-statistic under 1000 permutations of the class

labels with t13 density superimposed.

ty

Example of a null case: with 7 N(0,1) points and

8 N(10,9) points; histogram of the pooled two-sample

t-statistic under 1000 permutations of the class

labels with t13 density superimposed.

ty

The SAM Method

Use the permutation method to calculate the null

distribution of the modified t-statistic (Tusher et al., 2001).

The order statistics t(1), ... , t(N) are plotted against their null

expectations above.

A good test in situations where there are more genes being

over-expressed than under-expressed, or vice-versa.

Two-component Mixture Model Framework

Two-component model

f (t j ) 0 f 0 (t j ) 1 f1 (t j )

0 is the proportion of genes that are not

differentially expressed, and 1 1 0

is the proportion that are.

Two-component model

f (t j ) 0 f 0 (t j ) 1 f1 (t j )

0 is the proportion of genes that are not

differentially expressed, and 1 1 0

is the proportion that are.

Then

0 f 0 (t j )

0 (t j )

f (t j )

is the posterior probability that gene j is not

differentially expressed.

1) Form a statistic tj for each gene, where a large positive

value of tj corresponds to a gene that is differentially

expressed across the tissues.

2) Compute the Pj-values according to the tj and fit a mixture

of beta distributions (including a uniform component)

to them where the latter corresponds to the class of genes that

are not differentially expressed.

or

3) Fit to t1,...,tp a mixture of two normal densities

with a common variance, where the first component has the

smaller mean (it corresponds to the class of genes that are

not differentially expressed). It is assumed that the tj

have been transformed so that they are normally distributed

(approximately).

tj

4) Let ˆ0(tj) denote the (estimated) posterior probability that

gene j belongs to the first component of the mixture.

If we conclude that gene j is differentially

expressed if:

ˆ0(tj) c0,

then this decision minimizes the (estimated)

Bayes risk

where

Estimated FDR

where

Suppose 0(t) is monotonic decreasing in t. Then

ˆ0(tj ) c0

for

tj t 0.

1 F 0(t 0)

ˆ

FDR ˆ 0

1 Fˆ (t 0)

E 0(t ) | t t 0

Suppose 0(t) is monotonic decreasing in t. Then

ˆ0(tj ) c0

for

tj t 0.

1 F 0(t 0)

ˆ

FDR ˆ 0

1 Fˆ (t 0)

Suppose 0(t) is monotonic decreasing in t. Then

ˆ0(tj ) c0

for

tj t 0.

1 F 0(t 0)

ˆ

FDR ˆ 0

1 Fˆ (t 0)

where

F 0(t 0) (t 0)

ˆ

t

0

i

ˆ

F (t 0) ˆ 0(t 0) ˆi

ˆi

i 1

g

For a desired control level a, say a = 0.05, define

t 0 arg min FDˆ R(t ) a

t

If

1 F 0(t )

0

1 F (t )

(1)

is monotonic in t, then using (1)

to control the FDR [with ˆ 0 1 and Fˆ (t 0) taken

to be the empirical distribution function] is equivalent

to using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure based on

the P-values corresponding to the statistic tj.

Example

The study of Hedenfalk et al. (2001), used cDNA arrays to

measure the gene expressions in breast tumour tissues taken from

patients with mutations in either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes.

We consider their data set of M = 15 patients, comprising

two patient groups: BRCA1 (7) versus BRCA2-mutation

positive (8), with N = 3,226 genes.

The problem is to find genes which are differentially

expressed between the BRCA1 and BRCA2 patients.

Example of a null case: with 7 N(0,1) points and

8 N(0,1) points; histogram of the pooled two-sample

t-statistic under 1000 permutations of the class

labels with t13 density superimposed.

ty

Example of a null case: with 7 N(0,1) points and

8 N(10,9) points; histogram of the pooled two-sample

t-statistic under 1000 permutations of the class

labels with t13 density superimposed.

ty

Fit

0 N (0,1) 1 N ( 1 , )

2

1

to the N values of tj (pooled two-sample t-statistic)

jth gene is taken to be differentially expressed if

ˆ0 (t j ) c0

Estimated FDR for various levels of c0

c0

Nr

FDˆ R

0.5

1702

0.29

0.4

1235

0.23

0.3

850

0.18

0.2

483

0.12

0.1

175

0.06

Use of the P-Value as a Summary Statistic

(Allison et al., 2002)

Instead of using the pooled form of the t-statistic, we can work

with the value pj, which is the P-value associated with tj

in the test of the null hypothesis of no difference in expression

between the two classes.

The distribution of the P-value is modelled by the h-component

mixture model

h

f ( pj ) if ( pj;ai1, ai 2) ,

i 1

where a11 = a12 = 1.

Use of the P-Value as a Summary Statistic

Under the null hypothesis of no difference in expression for the

jth gene, pj will have a uniform distribution on the unit interval;

ie the b1,1 distribution.

The ba1,a2 density is given by

where

Outline of Tutorial

•Introduction to microarray technology

•Detecting Differentially Expressed Genes in Known Classes

of Tissue Samples

•Cluster Analysis: Clustering Genes and Clustering Tissues

•Supervised Classification of Tissue Samples

•Linking Microarray Data with Survival Analysis

Gene Expression Data represented as N x M Matrix

Sample 1 Sample 2

Expression Signature

Gene 1

Gene 2

Expression Profile

Gene N

Sample M

N rows correspond to the

N genes.

M columns correspond to the

M samples (microarray

experiments).

Two Clustering Problems:

Clustering of genes on basis of tissues –

genes not independent

(n = N, p = M)

•Clustering of tissues on basis of genes latter is a nonstandard problem in

cluster analysis

(n = M, p = N, so n << p)

5

4

3

2

1

0

-1

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

CLUSTERING OF GENES WITH

REPEATED MEASUREMENTS:

Medvedovic and Sivaganesan (2002)

Celeux, Martin, and Lavergne (2004)

Chapter 5 of McLachlan et al. (2004)

UNSUPERVISED CLASSIFICATION

(CLUSTER ANALYSIS)

INFER CLASS LABELS z1, …, zn of y1, …, yn

Initially, hierarchical distance-based methods

of cluster analysis were used to cluster the

tissues and the genes

Eisen, Spellman, Brown, & Botstein (1998, PNAS)

Hierarchical (agglomerative) clustering algorithms

are largely heuristically motivated and there exist a

number of unresolved issues associated with their

use, including how to determine the number of

clusters.

“in the absence of a well-grounded statistical

model, it seems difficult to define what is

meant by a ‘good’ clustering algorithm or the

‘right’ number of clusters.”

(Yeung et al., 2001, Model-Based Clustering and Data Transformations

for Gene Expression Data, Bioinformatics 17)

McLachlan and Khan (2004). On a

resampling approach for tests on the

number of clusters with mixture modelbased clustering of the tissue samples.

Special issue of the Journal of Multivariate

Analysis 90 (2004) edited by Mark van der

Laan and Sandrine Dudoit (UC Berkeley).

Attention is now turning towards a model-based

approach to the analysis of microarray data

For example:

• Broet, Richarson, and Radvanyi (2002). Bayesian hierarchical model

for identifying changes in gene expression from microarray

experiments. Journal of Computational Biology 9

•Ghosh and Chinnaiyan (2002). Mixture modelling of gene expression

data from microarray experiments. Bioinformatics 18

•Liu, Zhang, Palumbo, and Lawrence (2003). Bayesian clustering with

variable and transformation selection. In Bayesian Statistics 7

• Pan, Lin, and Le, 2002, Model-based cluster analysis of microarray

gene expression data. Genome Biology 3

• Yeung et al., 2001, Model based clustering and data transformations

for gene expression data, Bioinformatics 17

The notion of a cluster is not easy to define.

There is a very large literature devoted to

clustering when there is a metric known in

advance; e.g. k-means. Usually, there is no a

priori metric (or equivalently a user-defined

distance matrix) for a cluster analysis.

That is, the difficulty is that the shape of the

clusters is not known until the clusters have

been identified, and the clusters cannot be

effectively identified unless the shapes are

known.

In this case, one attractive feature of

adopting mixture models with elliptically

symmetric components such as the normal

or t densities, is that the implied clustering

is invariant under affine transformations of

the data (that is, under operations relating

to changes in location, scale, and rotation

of the data).

Thus the clustering process does not

depend on irrelevant factors such as the

units of measurement or the orientation of

the clusters in space.

Height

y Weight

BP

H W

H-W

BP

MIXTURE OF g NORMAL COMPONENTS

f ( x ) 1 ( x; μ1 , Σ1 ) g ( x; μg , Σ g )

where

2 log ( x; μ, Σ ) ( x μ) Σ ( x μ) constant

TT

11

MAHALANOBIS DISTANCE

( x μ )T ( x μ )

EUCLIDEAN DISTANCE

MIXTURE OF g NORMAL COMPONENTS

f ( x ) 1 ( x; μ1 , Σ1 ) g ( x; μg , Σ g )

k-means

σ II

Σ1 Σ gg σ

22

SPHERICAL CLUSTERS

Equal spherical covariance matrices

With a mixture model-based approach to

clustering, an observation is assigned

outright to the ith cluster if its density in

the ith component of the mixture

distribution (weighted by the prior

probability of that component) is greater

than in the other (g-1) components.

f ( x ) 1 ( x; μ1 , Σ1 ) i ( x; μi , Σi )

g ( x; μg , Σ g )

Figure 7: Contours of the fitted component

densities on the 2nd & 3rd variates for the blue crab

data set.

Estimation of Mixture Distributions

It was the publication of the seminal paper of

Dempster, Laird, and Rubin (1977) on the EM

algorithm that greatly stimulated interest in

the use of finite mixture distributions to

model heterogeneous data.

McLachlan and Krishnan (1997, Wiley)

• If need be, the normal mixture model can

be made less sensitive to outlying

observations by using t component densities.

• With this t mixture model-based approach,

the normal distribution for each component

in the mixture is embedded in a wider class

of elliptically symmetric distributions with an

additional parameter called the degrees of

freedom.

The advantage of the t mixture model is that,

although the number of outliers needed for

breakdown is almost the same as with the

normal mixture model, the outliers have to

be much larger.

Mixtures of Factor Analyzers

A normal mixture model without restrictions

on the component-covariance matrices may

be viewed as too general for many situations

in practice, in particular, with high

dimensional data.

One approach for reducing the number of

parameters is to work in a lower dimensional

space by using principal components; another

is to use mixtures of factor analyzers

(Ghahramani & Hinton, 1997).

Two Groups in Two Dimensions. All cluster information would

be lost by collapsing to the first principal component. The

principal ellipses of the two groups are shown as solid curves.

Mixtures of Factor Analyzers

Principal components or a

single-factor analysis model

provides only a global linear

model.

A global nonlinear approach

by postulating a mixture of

linear submodels

g

f ( x j ) i ( x j ; i , i ),

i 1

where

i Bi B Di (i 1,..., g ),

T

i

Bi is a p x q matrix and Di is a

diagonal matrix.

Single-Factor Analysis Model

Yj B U j e j

( j 1,..., n) ,

where U j is a q - dimensiona l (q p )

vector of latent or unobservab le

variables called factors and Bi is a

p x p matrix of factor loadings.

The Uj are iid N(O, Iq)

independently of the errors ej,

which are iid as N(O, D), where D

is

a

diagonal

matrix

D diag ( ,..., )

2

1

2

p

Conditional on ith component

membership of the mixture,

Y j i BiU ij eij (i 1,..., g ).

where Ui1, ..., Uin are independent,

identically distibuted (iid) N(O, Iq),

independently of the eij, which are iid

N(O, Di), where Di is a diagonal matrix

(i = 1, ..., g).

An infinity of choices for Bi for

model still holds if Bi is replaced by

BiCi where Ci is an orthogonal matrix.

Choose Ci so that

1

i

T

i

B D B

i

is diagonal

Number of free parameters is then

pq p q(q 1).

1

2

Reduction in the number of parameters

is then

1

2

{ ( p q ) 2 (p q)}

We can fit the mixture of factor analyzers model

using an alternating ECM algorithm.

1st cycle: declare the missing data to

be the component-indicator vectors.

Update the estimates of

i and i

2nd cycle: declare the missing

data to be also the factors.

Update the estimates of

Bi and Di

M-step on 1st cycle:

( k 1)

i

( k 1)

i

n

j 1

(k )

ij

n

j 1

for i = 1, ... , g .

/n

n

(k )

ij

y j /

j 1

(k )

ij

M step on 2nd cycle:

( k 1)

i

Β

( k 1)

i

D

where

Vi

( k 1/ 2 )

diag {Vi

(k )

i

(

( k )T

i

( k 1/ 2 )

(B B

(k )

i

Iq

(k )

i

( k )T

i

V

Vi

( k )T

i

(k )

i

( k 1 / 2 ) ( k )

i

i

( k 1/ 2 )

( k ) 1

i

D

Bi

(k )

i

( k 1/ 2 ) 1

i

(k1)T

i

B

(k )

i

) B

,

)

}

j 1

n

j 1

n

i ( y j ;

Vi ( k 1/ 2 )

i ( y j ;

)

( k 1 / 2 )

j i

j i

)(

y

)(

y

)

( k 1 / 2 )

( k 1)

( k 1) T

is given by

Work in q-dim space:

(BiBiT + Di ) -1=

Di –1 - Di -1Bi (Iq + BiTDi -1Bi) -1BiTDi -1,

|BiBiT+D i| =

| Di | / |Iq -BiT(BiBiT+Di) -1Bi| .

PROVIDES A MODEL-BASED

APPROACH TO CLUSTERING

McLachlan, Bean, and Peel, 2002, A Mixture ModelBased Approach to the Clustering of Microarray

Expression Data, Bioinformatics 18, 413-422

http://www.bioinformatics.oupjournals.org/cgi/screenpdf/18/3/413.pdf

Example: Microarray Data

Colon Data of Alon et al. (1999)

M = 62 (40 tumours; 22 normals)

tissue samples of

N = 2,000 genes in a

2,000 62 matrix.

Mixture of 2 normal components

Mixture of 2 t components

Clustering of COLON Data

Genes using EMMIX-GENE

Grouping for Colon Data

1

6

2

7

11

16

3

8

12

17

4

9

13

18

5

10

14

19

15

20

Clustering of COLON Data

Tissues using EMMIX-GENE

Grouping for Colon Data

1

6

2

7

11

16

3

8

12

17

4

9

13

18

5

10

14

19

15

20

Heat Map Displaying the Reduced Set of 4,869 Genes

on the 98 Breast Cancer Tumours

Insert heat map of 1867 genes

Heat Map of Top 1867 Genes

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

16

12

17

13

18

14

19

15

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

36

32

37

33

38

34

39

35

40

i

1

mi

Ui

146 112.98

i

11

mi

66

Ui

25.72

i mi

21 44

Ui

13.77

i mi

31 53

Ui

9.84

2

93 74.95

12

38

25.45

22 30

13.28

32 36

8.95

3

61

46.08

13

28

25.00

23 25

13.10

33 36

8.89

4

55

35.20

14

53

21.33

24 67

13.01

34 38 8.86

5

43

30.40

15

47

18.14

25 12

12.04

35 44 8.02

6

92

29.29

16

23

18.00

26 58

12.03

36 56 7.43

7

71

28.77

17

27

17.62

27 27

11.74

37 46 7.21

8

20

28.76

18

45

17.51

28 64

11.61

38 19 6.14

9

23

28.44

19

80

17.28

29 38

11.38

39 29 4.64

10

23

27.73

20

55

13.79

30 21 10.72

40 35 2.44

where

i = group number

mi = number in group i

Ui = -2 log λi

Heat Map of Genes in Group G1

Heat Map of Genes in Group G2

Heat Map of Genes in Group G3

Number of Components

in a Mixture Model

Testing for the number of components,

g, in a mixture is an important but very

difficult problem which has not been

completely resolved.

Order of a Mixture Model

A mixture density with g components might

be empirically indistinguishable from one

with either fewer than g components or

more than g components. It is therefore

sensible in practice to approach the question

of the number of components in a mixture

model in terms of an assessment of the

smallest number of components in the

mixture compatible with the data.

Likelihood Ratio Test Statistic

An obvious way of approaching the

problem of testing for the smallest value of

the number of components in a mixture

model is to use the LRTS, -2logl. Suppose

we wish to test the null hypothesis,

H 0 : g g 0 versus H1 : g g1

for some g1>g0.

We let Ψ̂ i denote the MLE of Ψ calculated

under Hi , (i=0,1). Then the evidence against

H0 will be strong if l is sufficiently small, or

equivalently, if -2logl is sufficiently large,

where

2 log l 2{log L(Ψˆ 1 ) log L(Ψˆ 0 )}

Bootstrapping the LRTS

McLachlan (1987) proposed a resampling

approach to the assessment of the P-value

of the LRTS in testing

H 0 : g g0

v

H1 : g g1

for a specified value of g0.

Bayesian Information Criterion

The Bayesian information criterion (BIC)

of Schwarz (1978) is given by

ˆ ) d log n

2 log L(

as the penalized log likelihood to be

maximized in model selection, including

the present situation for the number of

components g in a mixture model.

Gap statistic (Tibshirani et al., 2001)

Clest (Dudoit and Fridlyand, 2002)

Outline of Tutorial

•Introduction to Microarray Technology

•Detecting Differentially Expressed Genes in Known Classes

of Tissue Samples

•Cluster Analysis: Clustering Genes and Clustering Tissues

•Supervised Classification of Tissue Samples

•Linking Microarray Data with Survival Analysis

Supervised Classification (Two Classes)

Sample 1

.......

Sample n

.......

Gene 1

Gene p

Class 1

(good prognosis)

Class 2

(poor prognosis)

Microarray to be used as routine

clinical screen

by C. M. Schubert

Nature Medicine

9, 9, 2003.

The Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam is to become the first institution

in the world to use microarray techniques for the routine prognostic screening of

cancer patients. Aiming for a June 2003 start date, the center will use a panoply

of 70 genes to assess the tumor profile of breast cancer patients and to

determine which women will receive adjuvant treatment after surgery.

Selection bias in gene extraction on the

basis of microarray gene-expression data

Ambroise and McLachlan

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Vol. 99, Issue 10, 6562-6566, May 14, 2002

http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/99/10/6562

Supervised Classification of Tissue Samples

We OBSERVE the CLASS LABELS z1, …, zn where

zj = i if jth tissue sample comes from the ith class

(i=1,…,g).

AIM: TO CONSTRUCT A CLASSIFIER c(y) FOR

PREDICTING THE UNKNOWN CLASS LABEL z

OF A TISSUE SAMPLE y.

e.g.

g = 2 classes

C1 - DISEASE-FREE

C2 - METASTASES

Sample 1 Sample 2

Expression Signature

Gene 1

Gene 2

Expression Profile

Gene N

Sample M

LINEAR CLASSIFIER

FORM

c( y ) b 0 β y

β0 β1 y1 β p y p

T

for the production of the group label z of

a future entity with feature vector y.

FISHER’S LINEAR DISCRIMINANT FUNCTION

z sign c( y )

where

1

β S ( y1 y2 )

1

T 1

b 0 ( y1 y2 ) S ( y1 y2 )

2

and

y1 , y2 , and S are the sample means and pooled sample

covariance matrix found from the training data

SUPPORT VECTOR CLASSIFIER

Vapnik (1995)

c( y ) β0 β1 y1 β p y p

where β0 and β are obtained as follows:

min

β , b0

subject to j

0,

1

2

n

β j

2

z j c(y j ) 1 j

j 1

( j 1,, n)

1 ,, n relate to the slack variables

separable case

n

βˆ aˆ j z j y j

j 1

with non-zero â j only for those observations j for which the

constraints are exactly met (the support vectors).

n

c( y ) aˆ j z j y Tj y bˆ0

j 1

n

aˆ j z j y j , y bˆ0

j 1

Support Vector Machine (SVM)

REPLACE

y

by h( y )

n

c( y ) aˆ j h( y j ), h( y ) bˆ0

j 1

n

aˆ j K ( y j , y ) bˆ0

j 1

where the kernel function K ( y j , y ) h( y j ), h( y )

is the inner product in the transformed feature space.

HASTIE et al. (2001, Chapter 12)

The Lagrange (primal function) is

LP

1

2

n

n

n

β j a j z j C ( y j ) (1 j ) l j j

2

j 1

j 1

j 1

which we maximize w.r.t. β, β0, and ξj.

Setting the respective derivatives to zero, we get

n

β a j z j y j

(2)

j 1

n

a j z j

(3)

j 1

a j lj

( j 1, , n).

(4)

with a j 0, l j 0, and j 0 ( j 1, , n).

(1)

By substituting (2) to (4) into (1), we obtain the Lagrangian dual function

n

LD a j

j 1

n

n

aa

2

1

j 1 k 1

We maximize (5) subject to 0 a j

j

k

T

j

z j z k y yk

n

and

a

j 1

j

(5)

z j 0.

In addition to (2) to (4), the constraints include

a j z j c( y j ) (1 j ) 0

l j j 0

z j c( y j ) (1 j ) 0

(6)

(7)

(8)

for j 1, , n.

Together these equations (2) to (8) uniquely characterize the solution

to the primal and dual problem.

Leo Breiman (2001)

Statistical modeling:

the two cultures (with discussion).

Statistical Science 16, 199-231.

Discussants include Brad Efron and David Cox

GUYON, WESTON, BARNHILL &

VAPNIK (2002, Machine Learning)

LEUKAEMIA DATA:

Only 2 genes are needed to obtain a zero

CVE (cross-validated error rate)

COLON DATA:

Using only 4 genes, CVE is 2%

Since p>>n, consideration given to

selection of suitable genes

SVM: FORWARD or BACKWARD (in terms of

magnitude of weight βi)

RECURSIVE FEATURE ELIMINATION (RFE)

FISHER: FORWARD ONLY (in terms of CVE)

GUYON et al. (2002)

LEUKAEMIA DATA:

Only 2 genes are needed to obtain a zero

CVE (cross-validated error rate)

COLON DATA:

Using only 4 genes, CVE is 2%

GUYON et al. (2002)

“The success of the RFE indicates that RFE has a

built in regularization mechanism that we do not

understand yet that prevents overfitting the

training data in its selection of gene subsets.”

Error Rate Estimation

Suppose there are two groups G1 and G2

c(y) is a classifier formed from the

data set

(y1, y2, y3,……………, yn)

The apparent error is the proportion of

the data set misallocated by c(y).

Cross-Validation

From the original data set, remove y1 to

give the reduced set

(y2, y3,……………, yn)

Then form the classifier c(1)(y ) from this

reduced set.

Use c(1)(y1) to allocate y1 to either G1 or

G2.

Repeat this process for the second data

point, y2.

So that this point is assigned to either G1 or

G2 on the basis of the classifier c(2)(y2).

And so on up to yn.

Ten-Fold Cross Validation

1

Test

2

3

4

5

6

7

Training

8

9

10

Figure 1: Error rates of the SVM rule with RFE procedure

averaged over 50 random splits of colon tissue samples

Figure 3: Error rates of Fisher’s rule with stepwise forward

selection procedure using all the colon data

Figure 5: Error rates of the SVM rule averaged over 20 noninformative

samples generated by random permutations of the class labels of the

colon tumor tissues

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

Selection bias ignored:

XIONG et al. (2001, Molecular Genetics and Metabolism)

XIONG et al. (2001, Genome Research)

ZHANG et al. (2001, PNAS)

Aware of selection bias:

SPANG et al. (2001, Silico Biology)

WEST et al. (2001, PNAS)

NGUYEN and ROCKE (2002)

BOOTSTRAP APPROACH

Efron’s (1983, JASA) .632 estimator

B.632 .368 AE .632 B1

where B1 is the bootstrap when rule

the training sample.

* is applied to a point not in

Rk

A Monte Carlo estimate of B1 is

n

B1 Ej n

j 1

K

where

Ej IjkQjk

k 1

K

I

jk

k 1

with Ijk

1 if xj kth bootstrap sample

0 otherwise

and Qjk

*

1 if R k misallocates xj

0 otherwise

Toussaint & Sharpe (1975) proposed the

ERROR RATE ESTIMATOR

A(w) (1 - w)AE wCV2E

where

w 0.5

McLachlan (1977) proposed w=wo where wo is

chosen to minimize asymptotic bias of A(w) in the

case of two homoscedastic normal groups.

Value of w0 was found to range between 0.6

and 0.7, depending on the values of p, , and n1 .

n2

.632+ estimate of Efron & Tibshirani (1997, JASA)

B.632 (1 - w)AE wB1

where

.632

w

1 .368r

B1 AE

r

AE

(relative overfitting rate)

g

pi (1 qi )

(estimate of no information error rate)

i 1

If r = 0, w = .632, and so B.632+ = B.632

r = 1, w = 1, and so B.632+ = B1

MARKER GENES FOR HARVARD DATA

For a SVM based on 64 genes, and using 10-fold CV,

we noted the number of times a gene was selected.

No. of genes

55

18

11

7

8

6

10

8

12

17

Times selected

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

MARKER GENES FOR HARVARD DATA

No. of Times

genes selected

55

1

18

2

11

3

7

4

8

5

6

6

10

7

8

8

12

9

17

10

tubulin, alpha, ubiquitous

Cluster Incl N90862

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2C

(p18, inhibits CDK4)

DEK oncogene (DNA binding)

Cluster Incl AF035316

transducin-like enhancer of split 2,

homolog of Drosophila E(sp1)

ADP-ribosyltransferase (NAD+; poly

(ADP-ribose) polymerase)

benzodiazapine receptor (peripheral)

Cluster Incl D21063

galactosidase, beta 1

high-mobility group (nonhistone

chromosomal) protein 2

cold inducible RNA-binding protein

Cluster Incl U79287

BAF53

tubulin, beta polypeptide

thromboxane A2 receptor

H1 histone family, member X

Fc fragment of IgG, receptor,

transporter, alpha

sine oculis homeobox

(Drosophila) homolog 3

transcriptional intermediary

factor 1 gamma

transcription elongation factor

A (SII)-like 1

like mouse brain protein E46

minichromosome maintenance

deficient (mis5, S. pombe) 6

transcription factor 12 (HTF4,

helix-loop-helix transcription

factors 4)

guanine nucleotide binding

protein (G protein), gamma 3,

linked

dihydropyrimidinase-like 2

Cluster Incl AI951946

transforming growth factor,

beta receptor II (70-80kD)

protein kinase C-like 1

Breast cancer data set in van’t Veer et al.

(van’t Veer et al., 2002, Gene Expression Profiling Predicts

Clinical Outcome Of Breast Cancer, Nature 415)

These data were the result of microarray experiments

on three patient groups with different classes of

breast cancer tumours.

The overall goal was to identify a set of genes that

could distinguish between the different tumour

groups based upon the gene expression information

for these groups.

van de Vijver et al. (2002) considered a further 234 breast

cancer tumours but have only made available the data for

the top 70 genes based on the previous study of van ‘t Veer

et al. (2002)

Number of Genes

Error Rate for Top

70 Genes (without

correction for

Selection Bias as

Top 70)

Error Rate for Top

70 Genes (with

correction for

Selection Bias as

Top 70)

Error Rate for

5422 Genes (with

correction for

Selection Bias)

1

0.50

0.53

0.56

2

0.32

0.41

0.44

4

0.26

0.40

0.41

8

0.27

0.32

0.43

16

0.28

0.31

0.35

32

0.22

0.35

0.34

64

0.20

0.34

0.35

70

0.19

0.33

-

128

-

-

0.39

256

-

-

0.33

512

-

-

0.34

1024

-

-

0.33

2048

-

-

0.37

4096

-

-

0.40

5422

-

-

0.44

Nearest-Shrunken Centroids

(Tibshirani et al., 2002)

The usual estimates of the class means

overall mean y of the data, where

n

yi zijyj / ni

j 1

and

n

y yj / n.

j 1

yi are shrunk toward the

The nearest-centroid rule is given by

where yv is the vth element of the feature vector y and yiv ( y )v .

In the previous definition, we replace the sample mean yiv of

the vth gene by its shrunken estimate

v

where

1

1

1 2

mi (ni n )

Comparison of Nearest-Shrunken Centroids with SVM

Apply (i) nearest-shrunken centroids and

(ii) the SVM with RFE

to colon data set of Alon et al. (1999), with

N = 2000 genes and M = 62 tissues

(40 tumours, 22 normals)

Nearest-Shrunken Centroids applied to Alon data

(a) Overall Error Rates

(b) Class-specific Error Rates

SVM with RFE applied to Alon data

(a) Overall Error Rates

(b) Class-specific Error Rates

Outline of Tutorial

•Introduction to Microarray Technology

•Detecting Differentially Expressed Genes in Known Classes

of Tissue Samples

•Cluster Analysis: Clustering Genes and Clustering Tissues

•Supervised Classification of Tissue Samples

•Linking Microarray Data with Survival Analysis

Breast tumours have a genetic signature. The expression

pattern of a set of 70 genes can predict whether a tumour

is going to prove lethal, despite treatment, or not.

“This gene expression profile will outperform all currently

used clinical parameters in predicting disease outcome.”

van ’t Veer et al. (2002), van de Vijver et al. (2002)

Problems

•Censored Observations – the time of occurrence of the event

(death) has not yet been observed.

•Small Sample Sizes – study limited by patient numbers

•Specific Patient Group – is the study applicable to other

populations?

•Difficulty in integrating different studies (different

microarray platforms)

A Case Study: The Lung Cancer data sets from

CAMDA’03

Four independently acquired lung cancer data sets

(Harvard, Michigan, Stanford and Ontario).

The challenge: To integrate information from different

data sets (2 Affy chips of different versions, 2 cDNA arrays).

The final goal: To make an impact on cancer biology and

eventually patient care.

“Especially, we welcome the methodology of survival analysis

using microarrays for cancer prognosis (Park et al.

Bioinformatics: S120, 2002).”

Methodology of Survival Analysis using Microarrays

Cluster the tissue samples (eg using hierarchical clustering), then

compare the survival curves for each cluster using a non-parametric

Kaplan-Meier analysis (Alizadeh et al. 2000).

Park et al. (2002), Nguyen and Rocke (2002) used partial least

squares with the proportional hazards model of Cox.

Unsupervised vs. Supervised Methods

Semi-supervised approach of Bair and Tibshirani (2004), to combine

gene expression data with the clinical data.

AIM: To link gene-expression data with survival from lung cancer

in the CAMDA’03 challenge

A CLUSTER ANALYSIS

We apply a model-based clustering approach to classify tumour

tissues on the basis of microarray gene expression.

B SURVIVAL ANALYSIS

The association between the clusters so formed and patient

survival (recurrence) times is established.

C DISCRIMINANT ANALYSIS

We demonstrate the potential of the clustering-based prognosis

as a predictor of the outcome of disease.

Lung Cancer

Approx. 80% of lung cancer patients have NSCLC (of which

adenocarcinoma is the most common form).

All Patients diagnosed with NSCLC are treated on the basis of

stage at presentation (tumour size, lymph node involvement and

presence of metastases).

Yet 30% of patients with resected stage I lung cancer will die of

metastatic cancer within 5 years of surgery.

Want a prognostic test for early-stage lung adenocarcinoma to

identify patients more likely to recur, and therefore who would

benefit from adjuvant therapy.

Lung Cancer Data Sets

(see http://www.camda.duke.edu/camda03)

Wigle et al. (2002), Garber et al. (2001), Bhattacharjee et al. (2001),

Beer et al. (2002).

Genes

Heat Map for 2880 Ontario Genes (39 Tissues)

Tissues

Genes

Heat Maps for the 20 Ontario Gene-Groups (39 Tissues)

Tissues

Tissues are ordered as:

Recurrence (1-24) and Censored (25-39)

Expression Profiles for Useful Metagenes (Ontario 39 Tissues)

Gene Group 1

Gene Group 2

Log Expression Value

Our Tissue Cluster 1

Our Tissue Cluster 2

Recurrence (1-24)

Censored (25-39)

Gene Group 19

Gene Group 20

Tissues

Tissue Clusters

CLUSTER ANALYSIS via EMMIX-GENE of 20

METAGENES yields TWO CLUSTERS:

CLUSTER 1 (38): 23 (recurrence) plus Poor-prognosis

8 (censored)

CLUSTER 2 (8): 1 (recurrence) plus

7 (censored)

Good-prognosis

SURVIVAL ANALYSIS:

LONG-TERM SURVIVOR (LTS) MODEL

S (t ) prob.{T t}

1S1 (t ) 2

where T is time to recurrence and 1 = 1- 2 is the

prior prob. of recurrence.

Adopt Weibull model for the survival function for

recurrence S1(t).

Fitted LTS Model vs. Kaplan-Meier

Second PC

PCA of Tissues Based on Metagenes

First PC

Second PC

PCA of Tissues Based on Metagenes

First PC

Second PC

PCA of Tissues Based on All Genes (via SVD)

First PC

Second PC

PCA of Tissues Based on All Genes (via SVD)

First PC

Cluster-Specific Kaplan-Meier Plots

Survival Analysis for Ontario Dataset

• Nonparametric analysis:

Cluster

1

2

No. of Tissues No. of Censored

29

8

Mean time to Failure (SE)

665 85.9

1388 155.7

8

7

A significant difference between Kaplan-Meier estimates for

the two clusters (P=0.027).

• Cox’s proportional hazards analysis:

Variable

Cluster 1 vs. Cluster 2

Tumor stage (I vs. II&III)

Hazard ratio (95% CI)

P-value

6.78 (0.9 – 51.5)

1.07 (0.57 – 2.0)

0.06

0.83

Discriminant Analysis (Supervised Classification)

A prognosis classifier was developed to predict the class

of origin of a tumor tissue with a small error rate after

correction for the selection bias.

A support vector machine (SVM) was adopted to identify

important genes that play a key role on predicting the

clinical outcome, using all the genes, and the metagenes.

A cross-validation (CV) procedure was used to calculate

the prediction error, after correction for the selection bias.

ONTARIO DATA (39 tissues): Support Vector Machine

(SVM) with Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

0.12

Error Rate (CV10E)

0.1

0.08

0.06

0.04

0.02

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

log2 (number of genes)

Ten-fold Cross-Validation Error Rate (CV10E) of Support Vector

Machine (SVM). applied to g=2 clusters (G1: 1-14, 16- 29,33,36,38;

G2: 15,30-32,34,35,37,39)

STANFORD DATA

918 genes based on 73 tissue samples from 67 patients.

Row and column normalized, retained 451 genes after

select-genes step. Used 20 metagenes to cluster tissues.

Retrieved histological groups.

Genes

Heat Maps for the 20 Stanford Gene-Groups (73 Tissues)

Tissues

Tissues are ordered by their histological classification:

Adenocarcinoma (1-41), Fetal Lung (42), Large cell (43-47), Normal

(48-52), Squamous cell (53-68), Small cell (69-73)

STANFORD CLASSIFICATION:

Cluster 1: 1-19

(good prognosis)

Cluster 2: 20-26

(long-term survivors)

Cluster 3: 27-35

(poor prognosis)

Genes

Heat Maps for the 15 Stanford Gene-Groups (35 Tissues)

Tissues

Tissues are ordered by the Stanford classification into AC groups: AC

group 1 (1-19), AC group 2 (20-26), AC group 3 (27-35)

Expression Profiles for Top Metagenes (Stanford 35 AC Tissues)

Log Expression Value

Gene Group 1

Gene Group 2

Stanford AC group 1

Stanford AC group 2

Stanford AC group 3

Misallocated

Gene Group 3

Gene Group 4

Tissues

Cluster-Specific Kaplan-Meier Plots

Cluster-Specific Kaplan-Meier Plots

Survival Analysis for Stanford Dataset

• Kaplan-Meier estimation:

Cluster

1

2

No. of Tissues No. of Censored

17

5

Mean time to Failure (SE)

37.5 5.0

5.2 2.3

10

0

A significant difference in survival between clusters (P<0.001)

• Cox’s proportional hazards analysis:

Variable

Cluster 3 vs. Clusters 1&2

Grade 3 vs. grades 1 or 2

Tumor size

No. of tumors in lymph nodes

Presence of metastases

Hazard ratio (95% CI)

P-value

13.2 (2.1 – 81.1)

1.94 (0.5 – 8.5)

0.96 (0.3 – 2.8)

1.65 (0.7 – 3.9)

4.41 (1.0 – 19.8)

0.005

0.38

0.93

0.25

0.05

Survival Analysis for Stanford Dataset

• Univariate Cox’s proportional hazards analysis (metagenes):

Metagene

Coefficient (SE)

P-value

1

2

3

4

5

1.37 (0.44)

-0.24 (0.31)

0.14 (0.34)

-1.01 (0.56)

0.66 (0.65)

0.002

0.44

0.68

0.07

0.31

6

7

8

9

10

-0.63 (0.50)

-0.68 (0.57)

0.75 (0.46)

-1.13 (0.50)

0.73 (0.39)

0.20

0.24

0.10

0.02

0.06

11

12

13

14

15

0.35 (0.50)

-0.55 (0.41)

-0.61 (0.48)

0.22 (0.36)

1.70 (0.92)

0.48

0.18

0.20

0.53

0.06

Survival Analysis for Stanford Dataset

• Multivariate Cox’s proportional hazards analysis (metagenes):

Metagene

Coefficient (SE)

P-value

1

3.44 (0.95)

0.0003

2

-1.60 (0.62)

0.010

8

-1.55 (0.73)

0.033

11

1.16 (0.54)

0.031

The final model consists of four metagenes.

STANFORD DATA: Support Vector Machine

(SVM) with Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

0.07

Error Rate (CV10E)

0.06

0.05

0.04

0.03

0.02

0.01

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

log2 (number of genes)

Ten-fold Cross-Validation Error Rate (CV10E) of Support Vector

Machine (SVM). Applied to g=2 clusters.

CONCLUSIONS

We applied a model-based clustering approach to

classify tumors using their gene signatures into:

(a) clusters corresponding to tumor type

(b) clusters corresponding to clinical outcomes

for tumors of a given subtype

In (a), almost perfect correspondence between

cluster and tumor type, at least for non-AC

tumors (but not in the Ontario dataset).

CONCLUSIONS (cont.)

The clusters in (b) were identified with clinical

outcomes (e.g. recurrence/recurrence-free and

death/long-term survival).

We were able to show that gene-expression

data provide prognostic information, beyond

that of clinical indicators such as stage.

CONCLUSIONS (cont.)

Based on the tissue clusters, a discriminant analysis

using support vector machines (SVM) demonstrated

further the potential of gene expression as a tool for

guiding treatment therapy and patient care to lung

cancer patients.

This supervised classification procedure was used to

provide marker genes for prediction of clinical

outcomes.

(In addition to those provided by the cluster-genes

step in the initial unsupervised classification.)

LIMITATIONS

Small number of tumors available (e.g Ontario and

Stanford datasets).

Clinical data available for only subsets of the tumors;

often for only one tumor type (AC).

High proportion of censored observations limits

comparison of survival rates.