3.3 Contributions from mobile payment literature

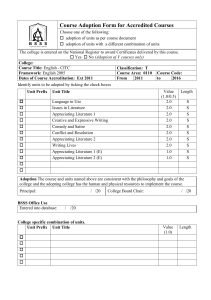

advertisement