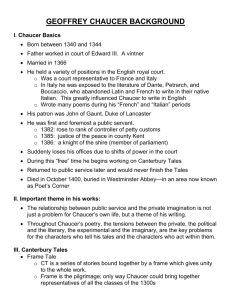

The father of English poetry

advertisement

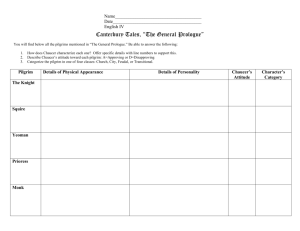

The father of English poetry, Geoffrey Chaucer was a late-14th century poet, born in London in the early 1340s. He lived through a time when there was immense fraudulence and overfancifulness in the medieval England. In his later years, he wrote the Canterbury Tales, in which he demarcated that era with his humor and realism. It is a social commentary of the values and customs prevailing in the medieval England. Initially, Chaucer intended to write 120 stories, each character was to tell four stories. However, later Chaucer wrote only 24 stories. The party went on its way to Canterbury and accomplished the religious journey. Chaucer either planned to revise the structure to cap the work at 24 tales, or else left it incomplete when he died on October 25, 1400. The finest part of the Canterbury Tales is the Prologue, and the noblest story is probably the Knight’s Tale. Pilgrimage was a very prominent feature of medieval society. In the Canterbury Tales, 29 pilgrims meet Chaucer at the Tabard in Southwark. The Prologue begins with giving the background of the journey – the poet describes the season and the desire for pilgrimages that is aroused in people’s hearts in spring. The tales are presented as a part of a story-telling contest by a group of pilgrims as they travel together on a journey from Southwark to the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. The prize for this contest is a free meal at the Tabard Inn at Southwark on their return. The Wife of Bath, Squire, Monk, Physician, and Franklin are most richly attired. The Prioress, the Monk, the Friar, the Summoner, and the Pardoner are connected to the church. Chaucer presents distinctive personal details of all the character by direct and indirect characterizations. The portrait of the unworthy churchmen exposes the hypocrisies and the flaws of the medieval society. Chaucer accomplished his goal of writing with deeper meaning and symbolism by using a gentle tone to reveal the prevailing social and political tensions rather than making overt political statements. The first portrait is of the Knight. The Knight is gentle in speech and he heads the table of honor of the Teutonic knights. Chaucer uses a gentle tone to reveal the irony directed against women and religion that was marred with the unworthy churchmen. His humor is free from satirical fittings. His realism is strikingly modern. He throws a lot of light on both the secular and the churchly life of the period. He is engaged in somewhat amused and detached observation of the gap between the ideal and the actual in human affairs. Two characters, the Pardoner and the Summoner, whose roles apply the church’s secular power, are both portrayed as deeply corrupt, greedy, and abusive. They represent the darker side of the church of the Middle Ages. A pardoner in Chaucer’s day was a person from whom one bought Church “indulgences” for forgiveness of sins, but pardoners were often thought guilty of abusing their office for their own gain. Chaucer’s Pardoner openly admits the corruption of his practice while hawking his wares. His physical characteristics are repellent; however, he thought that he rode in the latest style with hair loose and without wearing a hood. He had a goat’s voice. He was beardless and his yellow hair fell in thin strips over his shoulders. The Pardoner’s glaring eyes and limp hair illustrate his fraudulence. The very face of the Summoner is revolting and frightening to the children. His love of garlic, onions and strong drink are indicative of his coarse tastes. He could even “pull a finch” (that is, seduce a girl if he got the opportunity). Historians also think that summoners of that time were not paid enough money by the church to really make a living; thus, they may have had to depend upon bribery to get by. He brought persons accused of violating Church law to ecclesiastical court. He is a lecherous man whose face is scarred by leprosy. He gets drunk frequently and is not particularly qualified for his position. He spouts the few words of Latin he knows in an attempt to sound educated. The reputation of the greedy Summoner is enough to reveal how abuses pervaded the actions of the courts. Though, the Monk and the Prioress are not as corrupt as the Summoner and the Pardoner, they fall far short of the ideal for their orders. Both are expensively dressed, show signs of lives of luxury and flirtatiousness and show lack of spiritual depth. The Prioress has a few little delicate affectations (deliberate pretense and exaggerated display). She has pretensions to aristocratic affectations. She has learnt French; she copies the manners of the upper class and is very particular about her appearance. She has excellent table manners as she never allows morsel to fall on her breast. Her girlish accomplishments are viewed with tolerance and her cleanliness at meals is positively welcomed; however, the account makes one wonder what the table manners of others were like! She is somewhat out of touch with reality and her portrait exposes her misplaced ideals. Chaucer says that the Monk's lust is for riding and hunting. He tended to ignore the rules of St. Benet or St. Maur because of their strictness. The Monk led a life of luxury and was pragmatic man of the world, rather than being a simple-minded priest. Chaucer aptly exposes the worldliness of the Monk by ironic means. Chaucer employs irony to the portrait of the Friar as well. The Friar too had completely ignored the ideals of simplicity, purity and austerity (soberness). Roaming priests with no ties to a monastery, friars were a great object of criticism in Chaucer’s time. Always ready to befriend young women or rich men who might need his services, the friar actively administers the sacraments in his town, especially those of marriage and confession. However, Chaucer’s worldly Friar has taken to accepting bribes. Instead of helping the poor and the needy, he lead a life of loose morals. In every town, he knew the inn-keepers and bar-maids better than the poor and the lepers because he felt that there is no good in dealing with such lowly people. The only devout churchman in the company is the Parson who lives in poverty, but is rich in holy thoughts and deeds. The pastor of a sizable town, he preaches the Gospel and makes sure to practice what he preaches. He is everything that the Monk, the Friar, and the Pardoner are not. Each of Chaucer’s characters express different—sometimes vastly different—views of reality, creating an atmosphere of relativism (the philosophical doctrine that all criteria of judgment are relative to the individuals and situations involved, and there are no absolute truths). Each pilgrim portrait within the prologue might be considered as an archetypal description. Many of the ‘types’ of characters featured would have been familiar stock characters to a medieval audience—the hypocritical friar, the rotund, food-loving monk, the rapacious miller, the corrupt Summoner, and the depraved Pardoner. The Prioress, though a respectable young woman, was too worldly to be nunly. She does not suggest of the modesty of a nun. If the Prioress is too much a woman, the Monk is too much a man. His portrait is the same length as hers. He hunts hares and rides horses instead of studying, praying, and working. Chaucer’s idea of the pilgrimage as a narrative framework enabled him to bring together the widest possible cross-section of the medieval society. He shows the high and the low, the good and the bad, the ideal and the pragmatic. Each of the pilgrims can be easily defined by what is said in the Prologue and each portrait creates an impression that a real human being sits or stands before us. Therefore, going through the Prologue to The Canterbury Tales is like visiting a portrait –gallery. And Chaucer’s Tales offer a comic pageant of the 14th century life with the pilgrims revealing their habits, moods and private life indirectly through the stories they tell.