Gramsci at the Margins Radical Thought on the Margins Princeton

advertisement

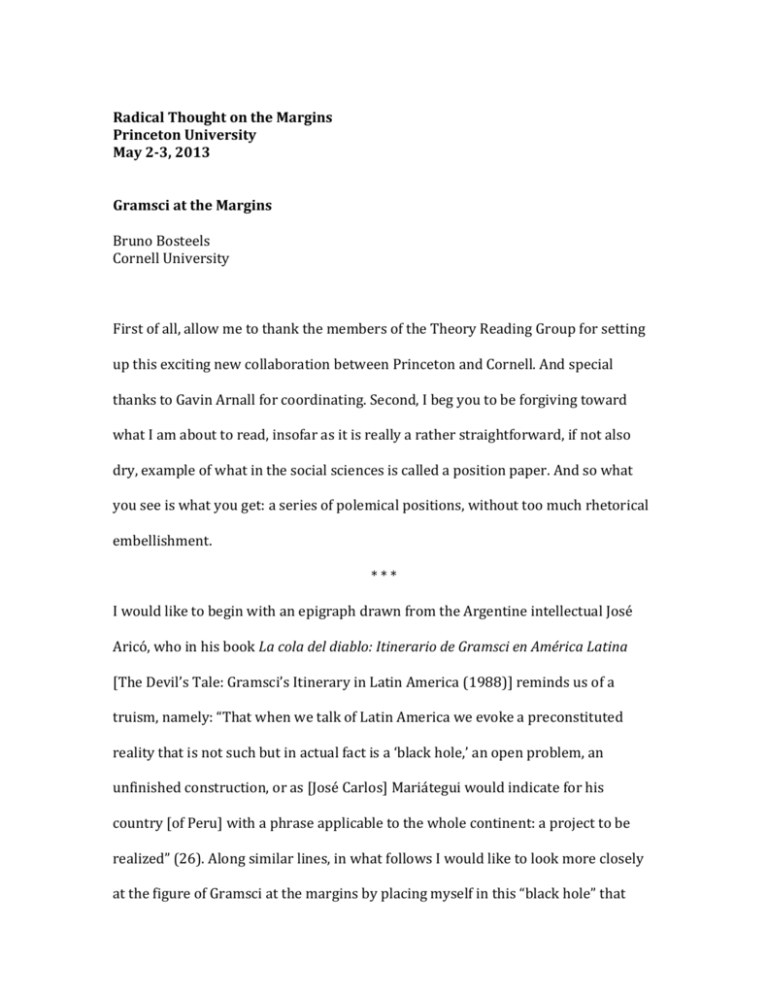

Radical Thought on the Margins Princeton University May 2-3, 2013 Gramsci at the Margins Bruno Bosteels Cornell University First of all, allow me to thank the members of the Theory Reading Group for setting up this exciting new collaboration between Princeton and Cornell. And special thanks to Gavin Arnall for coordinating. Second, I beg you to be forgiving toward what I am about to read, insofar as it is really a rather straightforward, if not also dry, example of what in the social sciences is called a position paper. And so what you see is what you get: a series of polemical positions, without too much rhetorical embellishment. *** I would like to begin with an epigraph drawn from the Argentine intellectual José Aricó, who in his book La cola del diablo: Itinerario de Gramsci en América Latina [The Devil’s Tale: Gramsci’s Itinerary in Latin America (1988)] reminds us of a truism, namely: “That when we talk of Latin America we evoke a preconstituted reality that is not such but in actual fact is a ‘black hole,’ an open problem, an unfinished construction, or as [José Carlos] Mariátegui would indicate for his country [of Peru] with a phrase applicable to the whole continent: a project to be realized” (26). Along similar lines, in what follows I would like to look more closely at the figure of Gramsci at the margins by placing myself in this “black hole” that Gramsci at the Margins 2 continues to be the unfinished construction of Latin America. In this process the black hole will morph into something like a Bermuda triangle that still threatens to cause the vanishing of Latin America as both object and subject of theory, both reality and terrain of radical thought today. *** The triangulation that I propose is between three recent books: Peter Thomas’s The Gramscian Moment: Philosophy, Hegemony and Marxism (first published in 2009; and then in 2010 in a more affordable paperback edition), Jon Beasley-Murray’s trendsetting Posthegemony: Political Theory and Latin America (also 2010), and Vivek Chibber’s fresh-off-the-press Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (2013). Simply put, my argument is that “Gramsci at the margins” is the name for the black hole at the center of this triangle. The three books are indeed connected primarily by way of complementary gaps, half-silences, and missed or truncated encounters. Let me summarize this in quick telegraph-style, before returning to some of the details later on: 1) Peter Thomas proposes a new Gramscian moment, based on the abandonment of all the dualisms such as state/civil society, coercion/hegemony, or West/East that unfortunately and much to his chagrin have become the consensus among latter-day Gramscians, but he fails to talks about non-European experiments such as the South Asian Subaltern Studies Group or the Latin American Gramscians. The absence of Latin America is even more ironic insofar as the alternative that Thomas proposes to the banalization of Gramscian dualisms is the concept of the Gramsci at the Margins 3 “integral State,” in its connection to “passive revolution” and “transformism,” which happen to offer the aegis under which Gramsci became a central theoretical figure in the Latin American landscape in the late 1970s and early 1980s. 2) Vivek Chibber, from a revitalized Marxist perspective, offers a frontal attack upon the postcolonial theory of the South Asian Subaltern Studies Group that rose up in the 1980s and 1990s, attacking the false dualisms that the Indian historians and intellectuals also borrowed in part from Gramsci, but he openly admits to having no interest in assessing how the ideas from Gramsci (or Althusser, for that matter) were disfigured or reconfigured at the hands of the Subalternist theorists (p. 27). He also does no more than occasionally reference the Latin American case—and even then only partially, namely, insofar as it is indebted to Guha & Co but without referencing, for example, the case of the historian Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui in Bolivia. Even among the US-based postcolonialists and subalternists, Chibber talks (without writing) about Aníbal Quijano and Walter Mignolo but remains silent about the work of John Beverley, Ileana Rodríguez, Alberto Moreiras or Gareth Williams. 3) Jon Beasley-Murray, a Latin Americanist who was a student of Moreiras’s, proposes a radical critique of hegemony as the basis for a new political theory which he calls posthegemony, opening up an agenda that already has been taken up actively in certain circles as the centralizing force for a revitalization of Latin American theory or “thought,” but he takes as his main interlocutor the strawman’s argument derived from all the imagined Gramsci at the Margins 4 dualisms (civil society/state, etc.) that Thomas has shown to be inaccurate based on a painstaking philological reconstruction of Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks and that Chibber will debunk for South Asian Subaltern Studies as being not only wrong but also ineffective in their alleged critique of peripheral capitalism and modernity. Missing from all three—to some extent justifiably so from the second book but much more problematically from the first and the third—is the genealogy of Gramsci at the margins and, more specifically, Gramsci’s itinerary in and for Latin America. Leaving aside for the moment Vivek Chibber’s understandable reluctance to tackle the exegetical question of judging the accuracy or inaccuracy of Gramsci’s reception in India, allow me to dwell a bit longer on the interlocking gaps with regard to Latin America and Gramsci that we find respectively in Peter Thomas and Jon Beasley-Murray. *** With regard to The Gramscian Moment: there are at least two ways to understand this title—with each of these readings, in turn, implying a radically different concept of the book’s project as a whole. On one hand, the title explicitly refers to the precise historical context of the composition of the Prison Notebooks and, more specifically, to the proposal, around 1932, of Gramsci’s distinct version of the philosophy of praxis. Thanks to his probing use of the critical edition of the Quaderni del carcere established by Valentino Gerratana in 1975, Peter Thomas is able to reconstruct this context with a unique combination of scholarly erudition and didactic clarity. On the other hand, it would seem that the “Gramscian moment” Gramsci at the Margins 5 might actually be still to come. Urged on by the forward-looking occasion provided by the critical edition, rarely taken up in English-language interpretations, Peter Thomas also wants to contribute to the definition of the future agenda for a fundamental research program of Gramscian-inspired Marxist investigations. “In this sense, he writes, we encounter the Prison Notebooks today as a potential ‘future in the past’, a neglected moment of the twentieth century that may offer us a possible point of orientation for the twenty-first” (442). Now how does relying on a patient historical reconstruction of the original Gramscian moment surrounding the Prison Notebooks strengthen the chances for another Gramscian moment of fundamental Marxist research that might as yet lie ahead of us? In a prolonged polemic with Perry Anderson’s study The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci, Peter Thomas tries answering this question by focusing on the various binaries that are typically said to define the Gramscian theory of hegemony, also popularized by theorists of “radical democracy” who follow in the footsteps of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. These are the binaries of hegemony and coercion, civil society and the state, war of positions and war of maneuvers, and, finally, West and East. Peter Thomas intervenes in this debate by radically shifting both the meaning of the terms and their orientation: away from the theory of hegemony as such and toward a refocusing of the interpretation of Gramsci’s key concepts in light of the category of the integral, or integrated, state. Indeed, if there is one idea that can be said to summarize all of The Gramscian Moment, it is that the author of the Prison Notebooks is first and foremost a philosopher of the integral state, and not of hegemony. From the theory of hegemony to the integral state: such Gramsci at the Margins 6 would be the shift proposed as the guiding thread behind The Gramscian Moment. In the words of Peter Thomas: “This guiding thread that organises all of Gramsci’s carceral research can be succinctly characterized as the search for an adequate theory of proletarian hegemony in the epoch of the ‘organic crisis’ or the ‘passive revolution’ of the bourgeois ‘integral State’” (136). Now, impressive as this articulation is, can we be sure that it will suffice to safeguard a vital future for Marxist philosophical research? Can it even account for the actual success and political relevance of alternative readings of Gramsci— otherwise than by labeling them philologically inaccurate, or by dismissing them as too banal even to be taken seriously? Finally, independently of the richness of Gramsci’s philosophy of praxis, why should the future of Marxism be limited to a program for fundamental philosophical research? Would Gramsci have agreed with this reduction of his lifelong project to matters of philosophy or—as in the title of our conference—to matters of radical thought? Insofar as the standard for judging a specific reading of Gramsci is here first and foremost defined in terms of philological accuracy, we are left wondering what to do with all those famous interpretations that, even while perhaps involving patent misreadings, have nonetheless marked the actuality of Gramsci over the past several decades. This question is perhaps nowhere more urgent than in the case of the Gramscian theory of hegemony popularized by the work of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. Would this work not have been more deserving of a polemical rebuttal than the much older readings by Louis Althusser and Perry Anderson? Peter Thomas brushes aside the entire “radical-democratic” tradition as “little more Gramsci at the Margins 7 than a second incarceration,” which is “just as guilty of a posthumous miscarriage of justice” as the Eurocommunist interpretation (45); and, about the interpretation of Gramsci as a harbinger of post-Marxism, he writes in another footnote: “The conversion of an unrepentant Communist militant who died in a Fascist prison cell into a harmless gadfly is surely among the most bizarre and distasteful episodes of recent intellectual fashion” (57 n. 46). Surely, given the actual success of Laclau and Mouffe’s version of Gramsci and their contributions to the renewed momentum of Gramscianism, we might have been better served had Peter Thomas taken on the challenge of a more painstaking engagement with post-Marxism, even as a fashionable miscarriage of justice. More significant than these quick dismissals are the obvious lacunae in The Gramscian Moment. If we had to name two places where Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks gained enormous momentum over the past few decades, who would fail to mention South Asia and Latin America? But Peter Thomas does not say a word about the work of either one of the “subaltern studies groups” associated with these two regions, nor does he speak of the intellectuals committed to theorizing the place of “passive revolution” and the so-called “transition to democracy” after the military dictatorships in Argentina or Brazil. This last omission is all the more serious insofar as these intellectuals—few of whom, incidentally, would self-describe as philosophers—were deeply committed as well to the idea that Gramsci is above all a thinker, not of hegemony so much as of the integral State. José Aricó, in the essays collected in La cola del diablo, offers us an initial set of clues that might help us fill this gap in The Gramscian Moment. Going back to Gramsci at the Margins 8 several international seminars on Gramsci’s presence in Latin America, one held in 1980 in Morelia, Mexico, and another in September 1985 at the Gramsci Institute in Ferrara, Italy, he interrogates precisely the reasons behind the “actuality” of Gramsci for that historical period in Latin America, when in Italy and France, contrary to what was the case in the 1970s, the influence of the Italian thinker already seemed to be waning. For Aricó, the incorporation of Gramscianism in Argentina was neither merely academic nor limited to a topic for philological reconstruction. Héctor Agosti in the 1950s, for instance, made Gramsci into a key referent for the Argentine Communist Party, soon to be followed in the 1960s and 1970s by the most variegated invocations of Gramsci as a Sorelian voluntarist, a Togliattian Guevarist, a proto-Maoist and, finally, a national-popular left-Peronist inspired by the shortlived promise of the Montoneros. In all of these cases, Aricó insists, the measuring stick for evaluating the actuality or inactuality of Gramsci for a Marxist program of militant investigations was not purely conceptual but politicoideological—with the central problem always being the distance and/or fusion between the workers’ movement and intellectuals. Why then, to return to The Gramscian Moment, would the value of Gramsci’s thought primarily be phrased in terms of a revitalisation of (Marxist) philosophy— especially in the Hegelian definition of philosophy as “its time expressed in thought” (289)? Even if, to correct Hegel, we add uneven and combined development, or the non-contemporaneity of the contemporary, to our understanding of the historicity of dialectical progression, what do we gain when Thomas concludes his masterful revision of Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks with a fundamental program for Gramsci at the Margins 9 philosophical research? But also, and above all, what do we lose in doing so? In this move from historical materialism to the philosophy of praxis, do we not lose sight of the actual praxis, precisely by remaining within the disciplinary bounds of philosophy? And is this praxis not meant to be political before being philosophical? With regard to Posthegemony the problem is exactly the reverse. Jon Beasley-Murray certainly raises all the right questions by putting the theory of hegemony to the test not of its philological accuracy but of its ability to grasp the political experiences of its time. However, this still may not help us to obtain a better grip on the figure of Gramsci at the margins. In all of Posthegemony, Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks are quoted exactly once, on the first page of the book’s Prologue, in a hackneyed rehearsal of the binary of hegemony and direct domination, of consent and coercion. This means that we never move beyond an extremely limited and fairly un-Gramscian concept of hegemony as consent, which is then criticized not just for being ineffective but for never having existed in the first place. “There is no hegemony and never has been,” Jon Beasley-Murray writes in the opening line of his Introduction subtitled “A User’s Guide.” He explains: “The fact that people no longer give up their consent in the ways in which they may once have done, and yet everything carries on much the same, shows that consent was never really at issue. Social order is secured through habit and affect: through folding the constituent power of the multitude back on itself to produce the illusion of transcendence and sovereignty” (ix). Posthegemony, therefore, seeks to redress this failure of theory by becoming part critique and part constitution: critique of hegemony and civil society theory, on one hand, and, on the other, constitution of an alternative theory based Gramsci at the Margins 10 on the power of the multitude through affect and habit rather than through reason and discourse. Posthegemony, in some respects, may seem to offer a research program similar to The Gramscian Moment. Both books seek to replace inaccurate or ineffective theories with more adequate ones. Both are in effect attempts at rearticulating something like a critical social theory. In the actual realization of this program, however, each of these two books almost seems to drive straight into the other’s blind spot. First, whereas Peter Thomas cannot stomach spending more than two lines of his philological reconstruction on the dismissal of Laclau’s theory of hegemony, for Jon Beasley-Murray he is the must-read stand-in for Gramsci himself: “Laclau’s version of hegemony is the single most influential formulation for the development of cultural studies. Laclau’s hegemony theory is also, by some distance, the most fully developed and the least reliant on some vague ‘common sense’” (40). Second, whereas it is the non-European Gramscians who are absent from Peter Thomas’s book, Jon Beasley-Murray’s Latin Americanist rebuttal of Laclau as the quintessential theorist of hegemony not only falls back upon the old binaries that Thomas had shown to be farcical caricatures, he also introduces a whole slew of new ones: to coercion and consent, direct domination and hegemony, posthegemonic theory—as if artificially to prolong the lifespan of an imaginary Gramscianism—adds the binaries of emotion and affect, transcendence and immanence, discourse and habit, people and multitude, constituted and constituent power (63). Most importantly, beyond a watered-down version of hegemony theory, in light of which Laclau is taken to task as a substitute for Gramsci, Jon Beasley- Gramsci at the Margins 11 Murray has nothing more to say to us than Peter Thomas—and admittedly perhaps this is not his goal either—about the trajectory of other Gramscians at the margins in Latin America: José Carlos Mariátegui, Héctor Agosti, Rene Zavaleta Mercado, José Aricó, Juan Carlos Portantiero… the list is long, if also overwhelmingly male, of all those writers and intellectuals whose work sought in Gramsci the wherewithal to think the contradictory and constantly shifting realities of their time. They did so, however, less through the category of hegemony than through notions such as passive revolution, transformism, or the integrated State. Aricó, for example, writes in La cola del diablo: “I believe there exists an abuse of Gramscian terminology that conspires against its true understanding and produces a syncretistic effect that renders the political discourse banal. A symptomatic case is the category of ‘hegemony,’ which has been extended to such a point that it ends up being finally unrecognizable in its specific connotations” (136). If the concept of hegemony is thus diluted and deformed beyond recognition into the fiction of an imagined Gramscianism, what can we really hope to accomplish by replacing or displacing it with the added ambivalence of a prefix onto posthegemony? *** For the discussion, a programmatic statement for radical thought on the margins: Gramsci and beyond. To supplement and extend Aricó’s La cola del diablo, we could map out two or maybe three moments in the Gramsci reception at the margins in Latin America. These are not exactly sequential in a strict chronological sense but stacked into uneven and partially overlapping layers: Gramsci at the Margins 12 1) There is the moment when Aricó et al. rely on Gramsci for the study of passive revolution, the revolution interrupted, revolution from above, or transformism, often also garnered in the name of the integral state as the dominant concept to understand the development of the bourgeois state in Latin America. 2) There is the moment when one-time collaborators of Aricó, like Emilio de Ípola (more Althusserian than Gramscian) and Juan Carlos Portantiero, upon their return to Argentina become consultants for the transition to democracy under Raúl Alfonsín. They propose a democratic “pact” that in theoretical terms relies very heavily on the dualism civil society/state, hegemony/coercion, so as to escape the nightmare of armed militancy and the dictatorship that weighs down on the shoulders of this generation, and find a way to move beyond classical Marxist analysis. 3) Later, especially under the influence of the South Asian Subaltern Studies group and its followers in Latin America led by John Beverley and Ileana Rodríguez et al. in the wake of the Sandinista electoral defeat of 1990, the cultural turn diagnosed and dismantled by Chibber keeps spreading and makes its influence felt also on the study of new social movements in Latin America, generally presented as influenced by Gramsci, in the sense of a refocusing of attention on civil society, culture, agency, etc. over and above the State, class analysis, party organization etc. This is particularly strong among Latin Americanists in the social sciences who embrace the cultural turn in books and anthologies published in the USA such as Cultures of Gramsci at the Margins 13 Politics, Politics of Cultures: Re-Visioning Latin American Social Movements. But the Indian Subalternists also impacted the work of historians such as Gilly, who (in North Carolina) comes to write an account of the 1994 Chiapas uprising, for example, in terms of the “moral economy” of peasant uprisings, communal regimes of power and obedience, and from this point of view (indebted to E.P. Thompson as much as to James Scott and Ranajit Guha) implicitly dismisses his own earlier Marxist (Trotskyist) historiography of the Mexican revolution as Eurocentric, tied to a bourgeois-individualist rights-oriented form of rationalist Enlightenment modernity. Gilly’s 1971 La revolución interrumpida was a title-concept borrowed from Gramsci via the Argentine Gramscian Héctor Agosti: “The definition of the emancipatory process as an ‘interrupted revolution’ is the transcription of the Gramscian notion of ‘rivoluzione fallita,’ as Agosti himself somewhat equivocally clarifies fifteen years later [talking in 1966 about his 1951 book Echeverría].” Aricó adds: “I do not want to be overzealous but even a superficial glance at Agosti’s book suffices to confirm the strict Gramscian filiation of the formula (the revolution interrupted due to the incapacity for widening the national process into a democratic revolution that mobilizes the peasant masses against the feudal remnants)” (139). To this panorama, it would be interesting to contrast the case of Bolivia. The work of Álvaro García Linera (Qhananchiri), for example, starts off from a book on the national question in Marx (up to the Grundrisse, the rest did not make it into the book De demonios escondidos y momentos de revolución: Marx y la Revolución Social Gramsci at the Margins 14 and las extremidades del cuerpo capitalista, part I, 1991), before moving on to the question of capitalism at the periphery, focusing on the anthropological accounts of the community or ayllu in the Andean region (relying on Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui as much as on French ethnographers such as Claude Meillassoux—the father of Quentin Meillassoux), but in explicit dialogue with the late Marx’s writings on ethnology and his drafts and letter to Vera Zasulitch. This is particularly strong in Forma valor y forma comunidad, written from prison in the 1990s (1995). Like Chibber and unlike his counterparts in South Asian Subaltern Studies, whose work was only gradually being read in Bolivia thanks to the work of historians such as Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, García Linera not only does not argue that capitalism’s “universalizing drive” is interrupted or thwarted in the colonies. He actually argues against the overemphasis placed on the communal and the site-specific, in favor of the need for an alternative universality—not in the sense of a romanticized “alternative modernity” but in the sense that the only existing universalism today, which is capital, cannot be undermined, let alone overcome, in the name of communal or communitarian autonomy alone. Furthermore, like Chibber (or Bolívar Echeverría in Mexico, with his various texts on Marx’s materialism, from the “Theses on Feuerbach” to the “Fragment on the machine”), García Linera sees no need (at least not in his texts from before The Plebeian Potential) to abandon Marx either in favor of an imagined Gramscianism or in favor of a resolute post-Marxism.