Affordable Access Coalition TNC 2015

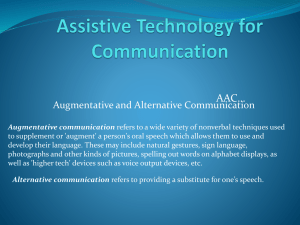

advertisement