Unintended Consequences

advertisement

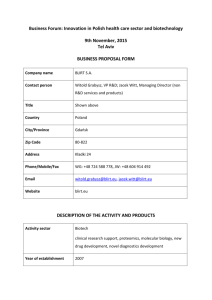

Unintended Consequences How science professors unintentionally discourage women of color 23 February 2007 • To download this presentation and some of the papers it is based on: • www.smcm.edu/users/acjohnson/Duke 2001 college grads All women College grads Science grads 57% 54% Data from www.nsf.gov/statistics, retrieved 28 Sept 2005 2001 college grads College grads Science grads All women 57% 54% Asian 3.3% 5.2% Data from www.nsf.gov/statistics, retrieved 28 Sept 2005 2001 college grads College grads Science grads All women 57% 54% Asian 3.3% 5.2% Black 5.6% 4.3% Hispanic 4.3% 3.6% American Indian .41% .37% Data from www.nsf.gov/statistics, retrieved 28 Sept 2005 2001 PhDs, working scientists All women Awarded science PhDs 39% Employed PhD scientists 23% Asian 4.9% 4.5% Black 1.5% .6% Hispanic 1.6% .7% American Indian .1% N/a Data from www.nsf.gov/statistics, retrieved 30 Sept 2005 The good news All women 1997 S&E grad 2004 S&E grad students students 40% 42% Asian 2.5% 2.9% Black 2.7% 3.1% Hispanic 1.8% 2.5% American Indian .2% .2% Data from www.nsf.gov/statistics/wmpd/sex.htm, Tables D-2 & D-3, retrieved 20 Feb 2007 The bad news • African American, Latino and American Indian students are less likely to graduate in science than similarly prepared White and Asian students (Huang, Taddese & Walter, 2000) • At CU Boulder: This pattern persists among declared science majors after controlling for financial need and preparation (Johnson, under review) Why this matters • Equity • Quality of science (Harding, 1991, 1993) • Employment patterns: altruistic science (Johnson, 2005) The question • Why are women--especially women of color--under-represented in the sciences? Explanations National Academies report Women are not as good in math Girls and boys perform the same in high school now Only a matter of time-- “Women’s not enough qualified representation women decreases with each step up the … hierarchies,” even in fields with lots of women for the past 30 years National Academies report Women faculty are less Women’s productivity is productive now comparable to men’s Women take more time Women take more time off due to children off early in their careers; over a lifetime, men take more sick leave than women Subconscious bias • Implicit Association test: 71% associate science with men, 9% associate it with women. • To take the test: implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/demo/ • For more info: www.projectimplicit.net/research.php Nosek, B. A., Smyth, F. L., Hansen, J. J., Devos, T., Lindner, N. M., Ranganath, K. A., Smith, C. T., Olson, K. R., Chugh, D., Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (2006). Pervasiveness and Correlates of Implicit Attitudes and Stereotypes.. Unpublished manuscript: University of Virginia. Seemingly neutral conditions • Seymour & Hewitt (1997), Talking About Leaving • ~350 well-prepared students, 7 institutions across the country • Some stayed in science, some left • All reported similar conditions Seemingly neutral conditions • • • • • • Hard classes Bad teaching Competition Fast pace Heavy work loads Unsupportive culture Seemingly neutral conditions • Masculine skill: rising to a challenge, without nurture • “Most women we encountered had entered college at a peak of self-confidence, based on good high school performances, good or adequate SAT scores and a great deal of encouragement and praise from high school teachers, family and friends” (255-256). Seemingly neutral conditions • “in treating male and female student alike, faculty are, in effect, treating women in ways that are understood by the men, but not by the women” (260). • White middle class skill: focus on individual goals Seemingly neutral conditions • Eisenhart & Finkel (1998), Women’s Science • Study of science workplaces which women believed were good for women • “For the most part, the women actually found easy access and success only insofar as they worked as if they were prototypical white males” (12). At last: Women of color • First: Some seemingly neutral conditions which disadvantage women of color • Next: Your responses • Then: Some possible solutions • And finally: More good news My study • Setting: Large Research I university, 85% white • Participants: 6 Black women, 7 Latinas, 3 American Indians, 4 Asian/Pacific Islanders • Academic preparation comparable to other science majors Data • 12 formal interviews • Participant observation in classes and labs (gen chem, honors chem, physics, environmental bio, molecular bio, o chem, plant anatomy, human anatomy) Data analysis • Searched for patterns of behavior and experiences • Generated assertions • Checked assertions against new data • Presented findings to participants • Focus groups with other women of color Findings • 3 discouraging practices in science classes • Large lecture classes • Asking and answering questions in class • Engaging in research Findings • Two discouraging cultural values • Focus on decontextualized science • Presentation of science as meritocratic, raceless and genderless Large lecture classes • The women… • Wanted to get to know professors • (Many) came from urban or rural schools where they were cherished • Found lectures alienating; felt conspicuous but also invisible It was a shock, literally a shock walking into my first class and seeing the teacher down there with the microphone, and seeing him like put up the screen on this huge—I mean, it’s bigger than our little theater in our town, I’m just like “oh my god,” you know, I mean it was huge, and I just couldn’t adjust to that. And I couldn’t adjust to the fact that I couldn’t talk to this teacher, you know, face-to-face. One, I didn’t have the time, and then they didn’t have the time. Because they were always doing other things, and they had like five hundred students in the first class, so it’s just like, they can’t take that much time just for you, you know. --American Indian woman, molecular biology major, now a pharmacist Alexis was in cell biology with us that year. And towards the last exam, Alexis and I went to go talk to the professor who was teaching— he’s a really good teacher. He [said] “strange, I don’t recognize you guys from my class. Do you sit in the back?” And in retrospect, I was like “Dang!” How could he miss us?? Me, Alexis and Derartu were the only Black people in the whole class! I was like “do you not look up?” I don’t know. “Next time we’ll sit on your little podium.” Even though, you know, maybe he didn’t recognize us legitimately, OK? There’s like three hundred people to stare at every day for six months or whatever. But still, I still just felt like not involved in the class, you know? Just kind of like a spectator of the class, like I’m not really a part of the learning process, I’m just kind of watching and hopefully getting a good grade. --Black woman, molecular biology major, now with a master’s in public health Asking and answering questions • Common tactic of professors • Seems laudable • Good way to be recognized by professors • Some students take advantage of it more than others • White men answered, white women asked, women of color were silent Asking and answering questions • Socialized as women not to draw attention • Felt conspicuous • Feared they alone, out of 250 students, were confused • All students seemed to have this opportunity but only some took it Like the classes were, you know, there’s a select few over-achievers who laugh at all the jokes, who ask questions, who ask the “challenge the professor” questions, who probably clone genes at home, I don’t know—it’s like those select few and the professor, and everybody else is just either asleep or just scribing every word they can get. And that’s just what I felt like—the class is just following along, and I’m just sort of like along for the ride. --Black molecular biology major Doing research • Some women in this study had outstanding experiences • Some had spectacularly bad experiences I like working in the lab because I get to go in there and I get to do all this stuff that you have no idea what you’re doing— because you work with things that you can’t see, right? And so you do a lot of stuff, and you don’t know what you’re doing, you don’t know if it’s going to work or whatever, and then you find out that it works, and you’re just kind of like “Wow, I did that, and it worked! And now I know that this species is not related to this species...” It was just all this work on trying to find out [using DNA sequencing] if some species were related, and how closely they were related. It was just learning—learning about things that you can’t see by using things that you can see. … After I graduate, I want to come back and do a doctorate, probably in genetics, some kind of genetics. And then I want to do research. I just find it fascinating! You’re always learning! That’s what I like—I like learning. Finding things out. --Latina molecular biology major, now a PhD-holding research scientist I did research my freshmen year in an environmental biology lab and it was sooooo boring to me. I was looking into a microscope 3-4 hours a day looking at fungi. How fun is that? I would go to the professor in charge of the lab with intent of getting course advice or help as far as what else my biology degree would get me. I was expecting a mentor, but that didn't happen. He was too busy for little ol’ me. Also one of his grad students accused me of stealing his favorite pen, which ended up being in his lab pocket the whole time and he eventually apologized. That is why I switched my major. Then I did paid research in a kinesiology lab my second year. That was cool, it was in a human cardiovascular lab. Then another student and I wrote a grant to go to Mexico—that was the best experience ever. And now I am doing my own independent stuff on diabetes in the Latino/Hispanic community. Anyway, my mentor is acting like it is such a hassle to work with me, so I don't know or care what is up with him. He just seems so distant. The whole purpose of having a mentor is to have that person MENTOR you. My lab now is highly male dominated. Sometimes I just feel so inferior, not only because I am a female, but because I am an undergraduate. I feel at times I have a double stereotype, a woman of color. -Latina kinesiology major, master’s in public health, now applying to doctoral programs Research: Mixed results • Intimate spaces, close contacts with professors • Some labs let women express their interest in science • Other labs amplified women’s feelings of alienation and difference Decontextualized science • Lectures and labs focused on minutiae of science • Seldom gave a big picture • Seldom talked about why information was interesting • “just pouring information at you in a sort of condescending way” Decontextualized science • Reasons women in the study liked science: • It’s interesting • Means to a health career • Interested in the human body • Felt slighted or alienated when these motivations were not acknowledged Decontextualized science • Professors centered interactions around science, not around students Some science professors only look to the science aspects, they’re only into the intellectual thing. I guess they have to be if they’re teaching that, but—I cannot expect them to be open-minded about different things, like your life, when you do get advice from them. Many people are just like “OK, this is the career, this very intellectual, Ph.D., Master’s, that kind of thing.” I think they should ask the question like “what do you want to do? What makes you happy?” --Asian American molecular biology major, completed PhD in biomedical sciences, now in medical school Merima: Whenever I go talk to molecular biology professors, they make me feel, I don’t know—he’s a nice teacher, but they make me feel stupid. [Chris & Monica: Uh-huh.] I couldn’t even divide ten thousand by ten—I was so nervous. One time he said “did you understand what I just said?” I said “uh-huh,” so he said “repeat in your own words,” and I couldn’t. The hard thing is that for med school, they want you to have two science recommendations. This summer I’m going to work with somebody, but I don’t know who else I could get a recommendation from. I’m not just going to go up to somebody, just because I went to their office hours. Angela: What are they doing that makes you feel stupid? Monica: They put you on the spot. Merima: And they’re not too friendly. If you don’t know the answer, they just wait. Chris: It’s like they expect you to know the answer. And then, if you don’t, they just wait. They don’t tell you the answer. Merima: And I can tell you a lot of molecular biology students feel like this. It’s not just me or Chris. Meritocracy • Belief that success in science comes only from talent • Well-intentioned belief, but: • Made some of the women feel like special cases, even more different I was doing my report on Graves’ Disease a couple weeks ago. There’s different genes related to Graves’ Disease, for different ethnicities, and for a long time, they were like “OK, it’s just this one gene,” but it was only found with white people. And I thought that was really interesting. But then in my presentation, I was like “should I mention the part about African Americans having a different gene?” And women get affected a lot more. And I thought “damn, that’s kind of messed up, that I should rethink presenting—it’s as normal to the disease as its symptoms, know what I’m saying?” But still, I sort of felt “damn, should I not mention that?” In class, if there’s one black person and you’re the only other colored person, you know that you’re going to get to know that person, just by that person being brown, because it’s just like—you always get called out in class, and you have nobody else to talk to, because they don’t know how it is to be brown, and in school, and it is totally different. --American Indian pharmacist In a class where there’s me and then like one or two other people of color, we all seem to stick together, and somehow we all end up being lab partners, or something like that. Some people may feel like they’re being left out, or they can’t interact with the white people in the class, or something like that, because it seems like whenever I’m sitting there and it’s time to pick your lab partner, whoever else is the minority in the classroom will come and find me. Most of my lab partners have been minorities. --Latina molecular biology major, now pursuing PhD in the biomedical sciences Meritocracy… • Made race and gender patterns seem like personal choices • Obscured common reasons women of color studied science Conclusions • Women in this study faced the same difficulties all science students faced • Weed-out courses • Multiple choice exams • Inaccessible professors Conclusions • They also faced unique difficulties • Felt conspicuous • Didn’t like to draw attention • Felt conflicted between their altruism & their professors’ decontextualized science • Interpreted decontextualization as hostility or lack of caring • Were skeptical of claims about meritocracy Difficulties came from • Pragmatism (big classes) • Good intentions (asking and answering questions in class, taking on research assistants) Success in these settings required… • Comfort with attention • Knowledge of how to succeed in an unsupportive environment • Comfort with personal interactions centered on information, not relationship • Race- and gender-blindness But the setting “seemed fair”… • Because rhetoric of meritocracy obscured racial and gendered patterns • Both the women in the study & professors explained women’s nonparticipation in individual terms--lack of interest, lack of preparation, lack of ability Feedback • Does this data--and my arguments about it--seem convincing? • Other seemingly neutral practices? Some solutions • Recognize that science has a culture which certain types of students may not be familiar with • Occasionally put science in context • Establish rapport with students during office hours or research • Mention race & gender where they make sense Other solutions?? Altruism • Subset of previous sample • 3 Black women, 4 Latinas, 3 American Indian women, 4 Asian/Pacific Islanders • Still in contact with them 5-6 years after original study • 13 of the 14 expressed specific altruistic values, often tied to science No matter what I choose to do, I’m sure it will be something like a doctor, a teacher, a counselor, something where I’m involved with other people and working, trying to help other people. --African American biology/psychology major, now an M.D. Altruism and science careers • Career goals as undergraduates: • Teaching science (4) • Using science to preserve the environment (3) • Health professions (10) Medicine as altruistic science And so, with medicine, I could have patients, and I could do clinical research, and stuff like that. Anything that I can do to help people would really make me feel good --Latina molecular biology major, now working on a PhD in biomedical sciences Medicine as altruistic science 1. medicine is fun, fascinating, 2. it is a career that will keep me interested and challenged, 3. the opportunity to serve many different people --2005 email, American Indian biology major, now an M.D. Medicine as altruistic science • Seven students specified desire to work with under-served populations Medicine as altruistic science From what I see, they’re the ones who don’t have all the means necessary to keep them really healthy. […] So I want to work with people of color. And I’m a person of color, and I want to see them be healthy, and do well, and help them succeed, just like I did. --American Indian M.D. Race and altruism • 5 students connected their altruism with their experiences as women of color and residents of medically under-served areas Race and altruism If you’re often put in a lesser position, or something like that, and you manage to get above that, but you see other people being subjected to it, then you want to do what you can to help them out of it, and make them see that there’s another way. --African American M.D. Altruism as a buffer In science settings: I get the feeling I do when I walk through somebody’s house with shoes on. Like I’m in somebody else’s home and I’m improperly walking, when I’m in science --African American molecular biology major, now in public health Sophomore year was like the year I was going to switch and become a teacher, and get my master’s—I don’t know what I was going to do, but it was going to be something else, and [the director of an enrichment program for students of color in science] was like “no, there is a way to find the union between social issues and science. Just stick with it.” And on that faith, on faith that he was right, I decided, “well, I’ll try it.” --African American public health worker I don’t really have a feel for the science department. But working with other people, and being active with other communities of color, you learn about their struggles and this or that, and so when you apply both of them together— biology and working with people—I can see that medicine is one way to connect them all. So that’s helping me achieve my goal. --American Indian M.D. Altruism as a bridge to science: I wasn’t as excited to work on plants as I was to work on animals, just because it didn’t really affect me whether or not this family belonged to this family or not, but now that I’ve been doing it, it’s really interesting, just like seeing the way that they go about doing it. --Latina molecular biology major, now working on PhD I remember studying about genetics and the base primers and blah blah, and here I am, doing it in real life…life a mad scientist. I used to think, this is just a job to provide the means for the ends (graduation). But now I am doing so well in this job and have learned how the worlds of hard science meet public health…. --2005 email, Latina kinesiology major, on working in a kinesiology lab to put herself through her master’s in public health. 7 years later…. • Engaged in research (natural or social sciences) with altruistic applications: 7 • • • • • AIDS prevention Maternal and child health Organ transplants Infection in American Indian populations Pharmaceuticals 7 years later…. • Health professionals (5) • Applying to medical school (1) • Organizing and recruiting women or women of color in the sciences (3) ??? • Your ideas of how any or all of this could be used to retain more able women of color in the sciences???