Latin American Independence (Lecture Version)

advertisement

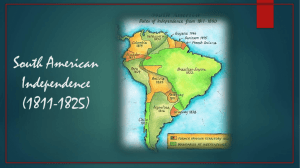

Major Battles and Campaigns during Spanish South American Independence Chapters: I--Colombia/Venezuela II--Argentina/Chile III--Peru All the highlights you need to know Colonial Latin America The Royalists (in Spanish: Realistas) were the American and European supporters of King Ferdinand. Hispanic Americans and Spaniards formed the Royalist Army, with Hispanic Americans composing 90% in all fronts. There were two types of units: the Expeditionary, units created in Spain; and the Militias, created in the Americas. They could be veteran units(Disciplined Militia). Only 11% were white people (Creole). In 1820, no more Spanish soldiers were sent to the war in the Americas. In 1820 there were only 9,954 Spanish soldiers in the Americas, and Spaniards formed only 10% of the whole Royalist Army, and only half of the soldiers of the expeditionary units were European. At the Battle of Ayacucho in 1824, less than 1% of the soldiers were European. El Libertador Simon Bolivar New Granada New Granada Independence was technically claimed in 1810 by Francisco Miranda, who fell from power in 1812 after a horrendous earthquake New Granada fell back into Civil War, with diff areas of the region controlled by diff armies. Young Bolivar, at that time a revolutionary, turned Miranda over to authorities in order to avoid jail time in a Spanish prison. Regrouped with other patriots in Venezuela and begin the famous Admirable Campaign Venezuela--the Admirable Campaign Venezuela--the Admirable Campaign The "Cartagena Manifesto“—unity and the liberation of Venezuela Trujillo and the "Decree of War to the Death." In the Decree Bolivar announced that the patriot army will treat Spaniards and Criollos differently: "Spaniards and Canarians, count on death, even if indifferent, if you do not actively work in favor of the independence of America. Americans, count on life, even if guilty." The Decree would remain in force, technically, until 1820. Bolivar’s forces had a triumphal entrance into the city of Caracas on 6 August, establishing the Venezuelan republic. Venezuela--the Admirable Campaign Venezuela--the reverses Despite the “liberation of Venezuela,” resistance continued against the revolution, this time from the llanero, and led by Tomas Boves -- the “horseman from Hell” Venezuela--the reverses Llaneros are the Venezuelan version of cowboys. They were mestizos who had ben pushed into the grasslands and had evolved their own culture. Boves had moved to the llano as a cattle rancher and became their leader. Why would they fight against Bolivar….? Venezuela--the reverses Boves scared the hell out of the criollos and was known for astonishing atrocities against the revolutionaries. He defeated Bolivar in 1814 at La Puerta, and then retook Caracas a month later-tho’ he died later that year. Bolivar was driven out of Venezuela and back to New Granada, where he spent two years trying to protect New Granada’s independence against Spanish forces until it fell to them in 1816. Venezuela remained loyal to Spain until 1821 Back to New Granada From 1814-1816, Spain sent an army to gain the province back. Internal divisions, prevented an easy unification of efforts. The provinces themselves did not give each other much needed aid. Many leaders decided to exile themselves, although others did remain in the region and tried to reorganize it military and political activities in order to face the new threat. Back to New Granada Due to these internal conflicts, on May 8, 1815, Simon Bolivar left his command under the United Provinces. Bolivar turned to Jamaica and later Haiti. Eventually, the growing exile community would also receive money, volunteers and weapons from the Haitian president and resumed the struggle for independence in the remote border areas of both New Granada and Venezuela, where they established irregular bands with the locals. This formed the early basis of an independent base from which the struggle to establish republics spread towards other colonial areas under Spanish control. By 1816, the combined efforts of Spanish and colonial forces completed the reconquest of New Granada, taking Bogota on May 6, 1816. A permanent war council was set up to judge those found guilty of treason and rebellion, resulting in the execution of more than a hundred notable republican personalities. Cartagena…key to New Granada New Granada In 1817, Bolivar decided to set up headquarters in the Orinoco region, which had not been devastated by war and from which the Spaniards could not easily oust him. He engaged the services of several thousand foreign soldiers and officers, mostly British and Irish, and established liaison with the revolutionary forces of the llanos, including one group of Venezuelan llaneros (cowboys) led by Jose Antonio Paez and another group of New Granadan exiles led by Francisco de Paula Santander. In the spring of 1819, he conceived his master plan of attacking New Granada Angostura congress—dictatorial powers, racial unity, abolition of slavery, elite controlled constitutional republic New Granada Bolivar's attack on New Granada is considered one of the most daring in military history, compared by contemporaries and some historians to Napoleon's crossing of the Alps in 1800 and Jose San Martin's Crossing of the Andes in 1817. The route that the small army of about 2,500 men--including a British legion--took went from the hot and humid, flood-swept plains of Venezuela lead through the icy mountain passes of the Cordillera Oriental. New Granada To help you understand how truly gnarly this is, consider the following: The Orinoco basin is in the center of the map, the river labeled in red. Now go from that to the upper left of the map to get to New Granada. Do that with an army, mostly on foot. Climb over these on your way… These would be the Andes… You know, where those soccer players ate each other in the ‘70s… On the route… New Granada The mostly llanero army was not prepared and poorly clothed for the cold and altitude of the mountains, and many became ill or died. The Spanish considered the route impassable, and therefore, they were taken by surprise when Bolivar's small army appeared in New Granada. At the Battle of Boyaca on August 7, 1819, the bulk of the royalist army surrendered to Bolivar. On receiving the news, the viceroy, Juan Jose de Samano, and the rest of royalist government fled the capital so fast that they left behind the treasury. On August 10 Bolivar's army entered Bogota. Battle of Boyaca Bolivar and his subordinate general, Santander, essentially trapped the royalist army led by a Col. Barreira as it tried to cross a bridge (La Puente de Boyaca,) and crushed it. The bridge is now a national site, and Colombian presidents are trotted out there every four years to celebrate the victory Battle of Boyaca Battle of Boyaca Battle of Boyaca Battle of Boyaca Historical consequences and legacy ・The final defeat of Royal forces in the New Kingdom of Granada and the weakening of the rest of the forces in all America. ・The royalist understand that the patriots were worthy of respect for their courage and heroism. ・The end of Spanish control over the American provinces, with the escape of viceroy Juan de Samano. ・The following freedom of all provinces in the New Kingdom.・The creation of Greater Colombia. ・The start of an autonomous government in the former Spanish provinces. ・The independence of Venezuela, Peru, Ecuador and the creation of Bolivia. In commemoration of this battle, August 7 is a national holiday in Colombia. Back to Venezuela Bolivar's chief preoccupation was to liberate his country (Venezuela). “I have created an army far superior to that of the enemy . . ." "I have instructed General Paez not to engage the enemy in any battle unless they are inferior in numbers and he is certain of destroying them without himself suffering heavy losses…” Battle of Carabobo--24 June 1821 The other major battle you need to know to write about Bolivar. This is the one that is considered the “Yorktown” of Venezuela. Keep in mind, however, the Spanish had withdrawn much of their army due to problems back in Europe. Nonetheless, it is a crucial moment both for Latin America and for Bolivar’s enshrinement as a continental hero. Battle of Carabobo--24 June 1821 Battle of Carabobo--24 June 1821 The Royalists occupied the road leading from Valencia to Puerto Cabello. As Bolivar's force of 6,500 approached the Royalist position, Bolivar divided his force and sent half on a flanking maneuver through rough terrain and dense foliage. Hitting the Patriots with musket fire, the Royalists held back the attack for a while. Bolivar’s infantry failed and retreated, but the Irish, Welsh, and English of the "British Legion" fought hard and took the hills. They sustained about 50% of Bolivar's casualties. The Patriots eventually broke through the Royalist lines on the flank. All the Royalist Venezuelan cavalry gave way and fled. The Spanish infantry formed squares and fought to the end under the attack of the Patriot cavalry. The rout was so bad that only some 400 of one infantry regiment managed to reach safety at Puerto Cabello. With the main Royalist force in Venezuela crushed, independence was ensured. Subsequent battles included a key naval victory for the independence forces on 24 July 1823 at the Battle of Lake Maracaibo and in November 1823 Jose Antonio Paez occupied Puerto Cabello, the last Royalist stronghold in Venezuela. The battle was remarkably one-sided. For every Patriot/Rebel death, 14-15 Spanish/Royalists were killed. This appears even more remarkable when one takes into account that it was fought near the end of the musket era, where frequently the victors on the battlefield would sustain almost as many casualties, if not more, than those they defeated. Bolivar’s Legacy Bolivar’s Legacy Bolivar is also a useful figure for current Latin American leaders to compare themselves to. Hugo Chavez of Venezuela insists he is not a leftist, but a “Bolivarian”-which to him signifies he will unite Latin America under his leadership and against US power. So, why’s he hugging this guy, then? That’s why he’s donating oil to other LA nations. The Viceroyalty of Argentina (Rio de la plata) The Viceroyalty’s office was centered in Buenos Aires Argentina By the nineteenth century Buenos Aires was becoming more self-sufficient, producing about 600,000 cattle a year (of which about one quarter was consumed locally), prompting the development of the area. But wars with Great Britain meant a great setback for the region's economy as maritime communications were practically paralyzed. The Alto Peru region started to show contempt as the expenses of administration and defense of the Rio de la Plata estuary were mainly supported by the declining Potosi production. For instance, in the first years of the viceroyalty, around 75% of the expenses were covered with revenues that came from the north. The Alto Plata (mostly present Paraguay) also had problems with the Buenos Aires administration, particularly because of the monopoly of its port on embarcations.By 1805, Spain had to help France because of their 1795 alliance, and had lost its navy in the Battle of Trafalgar, but the Spanish prime minister had warned the viceroyalty of the likelihood of a British invasion, and that in such an event the city of Buenos Aires would be on its own.In June 27, 1806 a small British force of around 1,500 men successfully invaded Buenos Aires after a failed attempt to stop him by viceroy Rafael de Sobremonte, who fled to Cordoba. The British forces were thrown back by the criollos on December 1806, a militia force under the leadership of Santiago de Liniers. Thus, lack of support from Spain and the confidence-boost by the fresh defeat of a world power prompted a movement towards independence at the expense of the viceroyalty. It was also clear that the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata was just several unrelated regions bound together in an attempt by the Spanish crown to maintain its power over the region. As of 1810, Argentina had been self-governed for about a year and Paraguay had already declared its independence, and the viceroyalty was effectively dissolved. Just to confuse you… the following areas of the viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata all declared independence on or around 1810… Paraguay…under Dr. Gaspar Rodriguez Francia, would remain independent despite Argentine hopes of keeping it Uruguay, under Jose Artigas, would eventually break free of Argentina by 1828 And the other vice-royalty of Chile, under Bernardo O’Higgins gained its independence, before Argentina declared its, but fell back into the grasp of Spain Argentina As you read, the Napoleonic campaign in Spain in 1810 had the effect of stimulating a junta in Buenos Aires to declare independence from the Bonaparte regime. What you really need to know about is the career of Jose de San Martin. Argentina Jose de San Martin (25 February 1778 - 17 August 1850), was an Argentine general and the prime leader of the southern part of South America's successful struggle for independence from Spain. In 1808, after joining the Spanish forces to fight against the French, San Martin started making contact with South American supporters of independence. In 1812, he offered his services to the United Provinces of South America (present-day Argentina).After the Battle of San Lorenzo in 1813, and some time in command of the Army of the North during 1814, he started his plan to attack Lima. This involved first creating an army in Cuyo, liberating Chile, and then attacking Lima by sea. In 1817, he crossed the Andes from Mendoza to Chile, and prevailed over the Spanish forces after the Battle of Chacabuco and liberated Chile in the Battle of Maipu (1818). San Martin seized partial control of the viceroyalty's capital (Lima) on July 12, 1821 and was appointed Protector of Peru. Peruvian independence was officially declared on July 28, 1821. After his closed-door meeting with fellow libertador Simon Bolivar at Guayaquil, Ecuador on 22 July 1822, Bolivar took over the task of fully liberating Peru. San Martin unexpectedly left Peru and resigned the command of his army, excluding himself from politics and the military, and he moved to France in 1824. Together with Simon Bolivar, San Martin is regarded as one of the Liberators of Spanish South America. He is the national hero of Argentina. Argentina--the battle of Chacabuco In 1814, having been instrumental in the establishment of a popularly elected congress in Argentina, Jose de San Martin began to consider the problem of driving the Spanish royalists from South America. He realized that the first step would be to drive them from Chile, and, to this end, he set about recruiting and equipping an army. In just under two years, he had an army of some 6,000 men with 1,200 horses and 22 cannons, and, on January 17, 1817, he set out with this force to cross the Andes and liberate Chile Argentina--the battle of Chacabuco The Army of the Andes (as San Martin's force was called) had suffered heavy losses during the crossing, losing as much as one-third of its men and more than half of its horses. The Royalist forces had rushed north to respond to their approach, and a force of about 1,500 under Brigadier Rafael Maroto blocked San Martin's advance at a valley called Chacabuco, near Santiago. In the face of the disintegration of the royalist forces, Maroto proposed abandoning the capital and retreating southward, where they could hold out and obtain resources for a new campaign. Royal Governor Field Marshal Casimiro Marco del Pont instead ordered Maroto to prepare for battle in Chacabuco. In order to keep discipline in the face of an attack the royalists knew they couldn’t oppose, Maroto “proclaimed a general decree on pain of death, to whomever suggested a retreat.” San Martin received numerous reports of the Spanish attack plans from a spy dressed as a roto, a poverty-stricken peasant of Chile. On February 11th, three days before his planned date of attack, San Martin called a war council to decide a plan of attack. Their main goal was to take the Chacabuco Ranch, the Spanish headquarters, at bottom of the hills. He decided to split his 2,000 troops into two parts, sending them down two roads on either side of the mountain. The right flank was led by Soler, and the left flank under O’Higgins. The plan was for Soler to attack their flanks while at the same time surrounding their rear guard in order to prevent their retreat. San Martin expected that both leaders attack at once so the Spanish had to fight a two-front battle. In the actual battle, the two flanks succeeded in forcing the Spanish into a defensive position in a cattle ranch, where the two Argentine flanks were able to surround them after heroic fighting by Soler and O’Higgins. Hand-to-hand combat ensued at the ranch until every Spanish soldier was dead or taken captive. 500 Spanish soldiers were killed and 600 taken captive. The Patriot forces only lost twelve men in battle, but an additional 120 lost their lives from wounds suffered during the battle. Argentina--the battle of Chacabuco Argentina--the battle of Maipu “The Battle of Maipu in 1818 is an extremely significant in South American history, for it was one of the most important battles of the Latin American struggle for independence. The feats that rebels achieved in the battle signified their dogged determination to remain free. The removal of a powerful, royalist army in Chile secured that country's sovereignty. The opening of a new land route to liberate Lima and destroy the Viceroyalty of Peru was achieved. The battle of Maipu was the culmination of southern South American independence, and also secured the sovereignty of Argentina, as well.” Argentina--the battle of Maipu Argentina--the battle of Maipu “Maipu became a rallying cry for Chilean nationalists up to the present, and it was a fine example of how a determined and uncompromising local force could vanquish a better-equipped, better trained professional army. San Martin had been granted control of the Chilean Pacific after Maipu, and this allowed him to effectively use British vessels, under Admiral Thomas Cochrane, to supply and transport his forces during the conquest of Peru. With Maipu and the subsequent victory at Lima, San Martin had secured his the destruction of the Viceroyalty of Peru, which had existed for over 200 years.” Argentina A word about Thomas Cochrane, the English officer who helped San Martin win the independence of Peru… Cochrane Cochrane became an English hero during the Napoleonic Wars, in which the French took to calling him “The Sea Wolf” for his daring tactics. He left England in disgrace, however, in 1817 due to a stock scandal and took a command in the Chilean navy at the behest of O’Higgins, where he was instrumental in not only besieging Spanish seaside forts despite being outnumbered in very engagement, but also in ferrying San Martin’s north into Peru after Maipu. Cochrane later schemed to free Napoleon from exile, just to do it, but was unsuccessful. For those of you who watched or read Master and Commander, Cochrane is the basis of hero Jack Aubrey, as well as of Horatio Hornblower (an earlier fictional sea-hero.) Bolivar and San Martin Meeting in 1822—San Martin bows out of high command Lima, Peru (capital of vice-royalty of Peru) threatened by remaining royalist forces in 1823, calls for Bolivar Bolivar lets the city be retaken briefly before retaking city in September 1823, to gain absolute authority over creole factions. Battling for one year, ending with Ayacucho in 1824