Women and Household Chores: An Argumentative Essay

advertisement

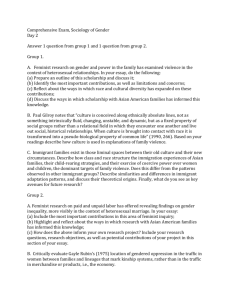

Stearman 1 Nicole Stearman Professor Kathy L. Rowley English 201-23 13 May 2012 Argumentative Essay: Women and All of Their Chores It should not be a surprise to anyone that women do more work around the house than men. Though, compared to the past, men have started to help out more at home, many women complain that they still do not do enough. Many claim that whether a person works or not determines whether he or she will actively participate in housework, but something of greater importance that needs more consideration is the innate male dominance that is prominent in society. Even if both the man and the woman of the house work, more often than not, the woman will be stuck with all of the chores assigned to them by society Despite the probability of both sexes being of the working class, women are likely to do more housework than men. According to Francine M. Deutsch: “Men do less housework because their greater incomes give them the power to opt out of it. However…inequality in the distribution of household labor persists even when women contribute half of the household income” (108). Even when women are working and contribute equally to the household income, they are still more inclined to do the majority of the housework. This is because men assume that cleaning the house is a woman’s job, because of how they were raised: under the traditional gender roles of society. However, not everyone views these gender roles in the same light. Examining the issue of the division of household labor in a seemingly “pessimistic” view,” one would consider the past as it relates to the present. According to Hilary Silver: “the ‘pessimistic’ view of homework draws on the role overload theory and labor history. It portrays Stearman 2 homework as a form of exploitive sweating that ties women to the dual demands of family and employers…subject[ing] them to their husband’s control” (184). By experiencing great amounts of pressure to do all of the homework in addition to having a job, women are vulnerable, making it easier for their husbands to control them. This pressure forces women to feel that they need to be the ones doing all of the homework. This “pessimistic” view is a bit extreme, recognition of the “optimistic” view making it seem even more excessive. When considering an opposing viewpoint, it seems that some people view housework as being a positive thing. People with such opinions would state that: “It allows households to optimize economic and time resources of their members, especially women” (184). By viewing housework as being able to make the best of a person’s time and money, undoubtedly would one advocate for women to take on the role of housework fully. This statement is desperately trying to justify the means of women being completely responsible for all of the homework, but it fails to prove to be a legitimate point of support. This weak argument is considered as such because it is of the minority; not many women brag about having to do most of the work around the house. With respect to the relationship between the economy and the housecleaning industry, people who are not a part of the industry are viewed as being “privileged.” According to Barbara Ehrenreich, “housework…was supposed to be the great equalizer of women” in the Sixties and Seventies. “Whatever else women did…we also did housework…some women who hired others to do it for them…seemed too privileged and rare to include in the theoretical calculus” (481). In the past, women used to be unable to find work, and so would stay at home with the children. This is the “equalizer” that Ehrenreich is referring to; as men were working, the women were doing housework at home. The idea of women not doing all of the housework was unheard of back in the Sixties and Seventies. It was just a fact that women were supposed to stay home and Stearman 3 attend to the house and kids. This is because of the domination of men over women, being present since the beginning of time. As the Feminist movement progressed, women began to question this inherent social structure. Many women viewed housework as one factor that makes women a lesser being than men: “Housework was not degrading because it was manual labor…but because it was embedded in degrading relationships and inevitably served to reinforce them” (483). This forced housework on women strengthened the notion that men were dominant over women. It was not the act of cleaning the house itself that made the situation humiliating, but the underlying consequences of it. Such consequences could include forms of gender oppression. This inherent male domination, to some extent, is a form of gender oppression: “When the person who is cleaned up after is consistently male, while the person who cleans up is consistently female, you have a formula for reproducing male domination from one generation to the next…Hence the feminist perception of housework…as [being] ‘a symbolic enactment of gender relations’” (483). Though the male in this situation is not physically taking control over the female, his dominance is symbolically expressed, having just as much of a negative effect on feminism. However, this male dominance does not affect women alone. Despite women being more commonly at home than men, there are still men who sometimes find themselves at home more often than women. However, these men seem to receive much flak from society, even if it is seemingly unintentional. Al Watts, a stay-at-homedad (SAHD), argues: “don’t call me ‘Mr. Mom.’ Call me ‘At-Home Dad.’ This clearly defines who I am without the negative connotation that I am somehow a replacement for mom or an incompetent homemaker or somehow less of a man” (“Don’t call me ‘Mr. Mom’”). Being called “Mr. Mom” makes men feel inferior to women, and makes them feel as if they are inadequate, Stearman 4 just “replacements” of women. Yet, as some men are quick to defend themselves after being called “Mr. Mom,” this seems to encourage a negativity to surround housework and childcare. It also encourages traditional gender roles, albeit Watts would prefer to be called “At-Home Dad.” This is because he vehemently opposes being called “Mr. Mom” because moms are notorious for being at home more often than men. Though most men do mind being called “Mr. Mom,” not all do. Calling a man who stays at home as his wife is out working, “Mr. Mom,” is supposedly an insult. However, this is not the case for all men. Indeed, some men, such as Adam W. McCoy, encourages the nickname: “I’ve decided being ‘Mr. Mom’ was worth it because of the great time I’ve had playing with my daughter and the laughter, the smiles and the times when she gives me a hug and says, ‘I love you, mommy’” (“Please Call Me ‘Mr. Mom’”). McCoy wanted to be called “Mr. Mom,” because he enjoyed spending so much time with his daughter. Though this article, being on the completely opposite side of the “Mr. Mom” spectrum, as opposed to the previous article, does not shine a negative light on SAHDs, it does encourage traditional gender roles. Moms are commonly associated with staying home and taking care of the kids, not dads. McCoy enjoys staying home with his daughter, but asked that people “please” do call him “Mr. Mom.” He would not simply be referred to as a “dad” because what he does is not typical of dads. McCoy is a SAHD that delights in what he does. Though not always in the same context, some women may share this sentiment. When considering housework, most people do not think about whether the person doing the chores enjoys what he or she is doing. Anyone would assume that no one enjoys doing housework, but Gemma Warren says differently: “I like doing housework because I can become absorbed in a physical activity that has nothing to do with education and everything to do with Stearman 5 concentrating on something else” (5). Warren is a teacher, and is exhausted after a day of instructing students. That is why she thinks of housework as a time of relaxation. Doing housework is simple, and does not require critical thinking. This greatly appeals to Warren, and probably many other women. When examining the division of labor from a marital perspective, the situation appears to be different. Considering the amount of work a housewife does, housewives seem to generally share the same sentiment as Warren, but not for the same reasons. Kluwer and others argue that “women are relatively satisfied with the unequal distribution of housework because the distribution (a) matches their comparison standard, (b) is perceived as justifiable, or (c) matches what they are socialized to want or value from their relationship” (959). Women are seemingly apathetic towards their doing the majority of the housework, because it is justifiable and it reflects their worth. Arguably, it could be said that women doing housework is “justifiable” because that is what they are supposed to be doing, because of the gender roles that society assigns to different genders. It is also justifiable because of how women compare to men. It is consistently found that men typically earn more money than women. This is not because of the type of job, because, in some cases, men and women may have the same job, but men are still earning more. This is because men are still viewed as being superior to women in society today. This reflects the ideologies of the past. With the Feminist movement, some have thought that women have moved on, gained their rights, and are now treated equally, but this is simply not the case. There is still much work to be done to establish true gender equality. Many contend that, in cases where men earn more money than women for the same job, the responsibility factor of the job is an important indicator in how much an employee will be paid. Undoubtedly, responsibility is significant when calculating the earnings of employees. Stearman 6 However, in several cases, the question of gender still seems to trump concerns of responsibility. One study suggests that “controlling for the effects of responsibility level, whether an employee is a man or a woman does have a statistically significant impact on his or her salary” (Sigelman et al. 668). Whether a person is a man or a woman is an important indicator of how much he or she will be paid. If she is a responsible woman, she will be paid less than a responsible man, just because she is a female. This is because of the dominance that men innately hold over women. The study said gender had a “significant” impact on an employee’s salary, meaning the difference is not small. If a woman was to complain about a difference of pay between her and her male coworker, odds are that said “difference” is not petty. In the same study, it was confirmed that “one could predict that if two employees—one male and the other female—hold equally responsible jobs, the man would be earning more than $2000 more than the woman” (668). The difference of pay between a man and a woman is not simply loose change, but in the range of thousands of dollars. This shows that society has a ways to go on the fight for gender equality, even when the working industry is supposed to be paying equally among people who work equally as much. In cases where responsibility is a legitimate factor over gender, there are some possible explanations. When regarding responsibility, some may have underlying problems in their lives, including depression, death of a family member, and chronic illnesses. These unfortunate events are inevitable, and they happen to everyone. However, people may experience such problems in the workplace. According to Amy S. Wharton: “Although the female labor force size and composition have changed during the past 15 years, studies of that period widely agree that women in predominantly-male occupations often experience hostility and harassment from male Stearman 7 coworkers, feelings of isolation, and stress due to high visibility” (365). Women are often oppressed in a male-dominated workplace, which can cause serious problems. Women already feel vulnerable because they are inferior to men, according to societal standards and expressed by scientific studies. Certainly this can be applied to places outside the workplace, and to everyday life. Even if women are not being physically oppressed by men, there is still shadow of male dominance, and it is seen everywhere. Most of the time, in a home setting, women do more housework than men. In a work setting, if women do the same amount of work than men, they will still be paid less. Either way, women are not acknowledged for all of the work that they do. Men dominate society, leaving little room for women to thrive equally. Because of this, and the encouragement of traditional gender roles, there is still much gender inequality that needs to be addressed and corrected, in all aspects of life, including the workplace and at home. Stearman 8 Works Cited Deutsch, Francine M. “Undoing Gender.” Gender and Society (2007): 106-127. JSTOR. Web. 7 May 2012. Ehrenreich, Barbara. “Maid to Order: The Politics of Other Women’s Work.” From Inquiry to Academic Writing. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2008. Print. Kluwer, Esther S., Heesink, Jose A. M., and Evert Van de Vliert. “Marital Conflict about the Division of Household Labor and Paid Work.” Journal of Marriage and Family (1996): 958-969. JSTOR. Web. 8 May 2012. McCoy, Adam W. “Please Call Me ‘Mr. Mom.’” ShorewoodPatch. Patch, 16 Jan. 2011. Web. 13 May 2012. Sigelman, Lee, Milward, H. Brinton, and Jon M. Shepard. “The Salary Differential between Male and Female Administrators: Equal Pay for Equal Work?” The Academy of Management Journal (1982): 664-671. JSTOR. Web. 8 May 2012. Silver, Hilary. “Homework and Domestic Work.” Sociological Forum (1993): 181-204. JSTOR. Web. 7 May 2012. Warren, Gemma. “I have turned into many things since I became a teacher, but I never thought my career would turn me into a domestic goddess.” The Times Educational Supplement (2001): 5. LexisNexis Academic. Web. 23 April 2012. Watts, Al. “Don’t call me ‘Mr. Mom.’” Momaha Blogs. Omaha World-Herald, 10 May 2012. Web. 13 May 2012. Wharton, Amy S., and James N. Baron. “Satisfaction? The Psychological Impact of Gender Segregation on Women at Work.” The Sociological Quarterly (1991): 365-387. JSTOR. Web. 8 May 2012.