Introduction to Ethics in Economics

advertisement

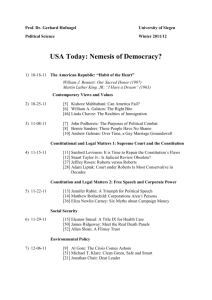

Ethics and Economics Jonathan B. Wight Contact Information: Professor of Economics University of Richmond Richmond, VA 23173 (804) 289-8570 jwight@richmond.edu © Jonathan B. Wight 1 Economics Economics is a “way of thinking” to help students understand the ramifications of actions. It is a tool to help students make more informed judgments. One of the most powerful concepts in economics is thinking at the margin when evaluating costs and benefits. © Jonathan B. Wight 2 Chevrolet Malibu But a jury fined General Motors $4.9 billion in punitive damages (July 1999) – for thinking at the margin! © Jonathan B. Wight 3 GM’s private calculation: * MC to fix the faulty fuel tank: $8.59 per car. * MB to fix the faulty fuel tank: $2.40 per car (savings from wrongful death and disfigurement lawsuits @ $200,000 on average) The “efficient” solution was chosen not to fix the faulty fuel tank. (Does this pass the ethical smell test?) Source: http://www.safetyforum.com/gmft/. The punitive damages against GM were later lowered by a judge to $1 billion. © Jonathan B. Wight 4 Economists have extolled short-run profit maximizing—in a moral vacuum. http://www.sciencecartoonsplus.com/gallery/ethics/eth06.gif © Jonathan B. Wight 5 Ethics is the consideration of “right” and “wrong.” It is penny-wise and pound foolish to ignore ethical considerations. Yet the American Economic Association complains that graduate schools keep turning out “idiot savants, skilled in technique but innocent of real economic issues” (Barber 1997, p. 98) © Jonathan B. Wight 6 Is our commercial system based on ... © Jonathan B. Wight 7 Economics or ... © Jonathan B. Wight 8 ...Greedonomics? © Jonathan B. Wight 9 Wall Street © Jonathan B. Wight 10 Wall Street © Jonathan B. Wight 11 Wall Street © Jonathan B. Wight 12 © Jonathan B. Wight 13 © Jonathan B. Wight 14 © Jonathan B. Wight 15 Arthur Andersen Enron East Asia WorldCom © Jonathan B. Wight 16 Walter Williams (Former chair, Dept. of Economics, George Mason University) “Free markets, private property rights, voluntary exchange, and greed produce preferable outcomes most times and under most conditions.” --“The Virtue of Greed in Promoting Public Good,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 6, 1999, p. A15) © Jonathan B. Wight 17 “[G]reed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself.” --Commencement address, May 18, 1986, School of Business Administration, University of. California, Berkeley. Ivan Boesky, leaving a federal halfway house in 1989. Six months later Boesky was convicted of insider trading … …and received a sentence of three years in prison and $100 million fine. © Jonathan B. Wight 18 Gordon Gekko in Wall Street (1987) “[G]reed is good.... Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit....” © Jonathan B. Wight Video 19 Is Adam Smith to Blame? Adam Smith, “gave a new dignity to greed,” and sanctified “predatory impulses” (Lerner, 1937, x). More than 250 years ago, Smith wrote: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.” Visual 2.1 (Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Indianapolis: Liberty Press, 1981 [1776], 26-27) © Jonathan B. Wight 20 Do we really understand Adam Smith? What would he say – if he came back to life? A novel Jonathan B. Wight, Saving Adam Smith: A Tale of Wealth, Transformation, and Virtue (Prentice Hall, 2002). © Jonathan B. Wight 21 Smith’s bottom line: It is appropriate to be self-interested. But moral considerations generate self-restraint, and beyond that, a concern for justice. Greed is self-interest… without the moral restraint. © Jonathan B. Wight 22 Ethical people generate the social capital that lubricates the wheels of commerce and society. “When the happiness or misery of others depends in any respect upon our conduct, we dare not, as self-love might suggest to us, prefer the interest of one to that of many.” (TMS, pp. 137-8) “[B]y acting according to the dictates of our moral faculties, we necessarily pursue the most effectual means for promoting the happiness of mankind….” (TMS, p. 166) © Jonathan B. Wight 23 The Invisible Hand Self-interest is a tremendous force for individual self-betterment. In “many” cases, self-interest also advances the interests of society The example Smith gives is of a businessman who prefers to keep his investments domestically because, “He can know better the character and situation of the persons whom he trusts...” (Wealth of Nations, 1981, 454). Social capital thus creates a bias in favor of domestic investments. This strengthens the domestic economy and creates spill-over benefits for society at large. See: Jonathan B. Wight, “The Treatment of Smith’s Invisible Hand,” Journal of Economic Education (forthcoming). © Jonathan B. Wight 24 Thus: “By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, [the entrepreneur] intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.” Sociability and trust—along with competitive markets and a system of justice—create conditions in which self interest promotes the broader interests of society. © Jonathan B. Wight 25 Lesson 2 Play the Ultimatum Game (p. 24) © Jonathan B. Wight 26 VISUAL 2.2 THE ULTIMATUM GAME: DIRECTIONS You are about to play a famous game called the Ultimatum Game. In this game players negotiate the division of 10 rewards items. The teacher will define the specific rewards to be allocated. Read these rules, but don’t begin to play until your teacher says “Go.” 1. You play this game in pairs; one player is the Proposer and the other is the Responder. 2. If you are the Proposer, your job is to propose an allocation, or division, of 10 rewards items between yourself and a Responder. You may not use fractional amounts, so you must propose a whole number between 0 and 10 rewards for yourself, with the remainder of the 10 rewards going to the Responder. © Jonathan B. Wight 27 VISUAL 2.2 THE ULTIMATUM GAME: DIRECTIONS (con’t) 3. If you are the Responder, your job is to accept or reject the Proposer’s proposal. If you accept the proposal, both of you will get the proposed number of rewards at the end of the lesson. If you reject the offer, neither of you will get anything for this round. 4. Proposers will randomly pick Responders for each round (try not to pick your close friends). Players must switch partners after each round. Do not repeat partners. 5. Half the class will start the game as Proposers and half as Responders. You will play two rounds, with a new partner for each round. After the second round, you will switch roles: Each Responder becomes a Proposer, and each Proposer becomes a Responder. You will play two more rounds — again, with a new partner for each round. © Jonathan B. Wight 28 VISUAL 2.2 THE ULTIMATUM GAME: DIRECTIONS (con’t) 6. Record your results after each round on the score sheet below. At the end of the game, calculate the total rewards you earned. 7. All rewards will be distributed at the end of the lesson. © Jonathan B. Wight 29 Visual 2.2 THE ULTIMATUM GAME This is the record sheet each student keeps. 1. In the column marked (P), circle the number of rewards you earned as a Proposer. 2. In the column marked (R), circle the number of rewards you earned as a Responder. 3. Add up the total rewards you earned as both a Proposer and Responder. © Jonathan B. Wight 30 The Bottom Line Self-interest may lead people to make aggressive offers, but greed can often lead to earning nothing. In the Ultimatum Game and in life, people dislike unfairness and will incur costs to punish it. Human nature includes the instincts for social cooperation and justice. Questions or comments? © Jonathan B. Wight 31 Positive economics – the study of what “is” Positive economic models become more powerful when we consider that human beings are partially motivated by sociability and morals. Examples * Highway tips * Doctor and patients * Auto mechanics and customers * Employees and fiduciary duties Ethical norms and judgments are pervasive—including in economics! © Jonathan B. Wight 32 Example from Lesson 1 – Does Science Need Ethics? Maria’s research project • • • • • Picking a professional field Picking a subject for study Perception and model-building Methodology and data collection Analysis, Dissemination and Impact Text, p. 11 © Jonathan B. Wight 33 Ideology = the characteristic thinking or beliefs of a particular group, culture or class at a point in time. Worldview = Ideology plus random knowledge (pre-analytical) World view and ethical judgments permeate research at every step. © Jonathan B. Wight 34 PROVIDE FACTUAL ANSWERS TO THESE QUESTIONS: 1. What is the current time? 2. What is this? 3. Does this animal pictured here eat: a) carrots from the garden b) fish from the lake? © Jonathan B. Wight 35 1. What is the current time? A. Did you answer “9:50”? Why didn’t you say, “It is exactly 9:50:43:50 a.m.”? You likely put the question of fact determination into a context. How important is the exact detail? You automatically filtered the question and added a value judgment about how much detail to add. B. Did you answer based on time in Las Vegas, NV? Why didn’t you say, “It is 6:20 pm in London, England? [Again, you put the question of fact determination into a context.] © Jonathan B. Wight 36 What is the current time? C. More importantly, where does the concept of time and its measurement come from? Why is each day broken up into 24 segments called “hours” and not into 12 or 15 or 30 segments? Where does each day “officially” start on the globe, and why there? What is Greenwich Mean Time, and how did this arise? © Jonathan B. Wight 37 2. What is this? A. Did you answer “an apple”? Why not manzana (Spanish) or apfel (German) or 苹果 (Chinese) ? Language is a human construct. Words that exist for concepts in one language may not exist in others, or may have multiple interpretations (e.g., “love”). What are the “facts” about what this thing is? © Jonathan B. Wight 38 2. What is this? B. Moreover, this is NOT factually an apple in any language. It is a two-dimensional representation of something you interpret to be an apple. Technically it is a spectrum of light particles bouncing off a reflective surface. © Jonathan B. Wight 39 KUHNIAN WORLDVIEW: Is this a duck or a rabbit? Around Easter, more children see the animal as a rabbit. Context determines the “facts” collected. © Jonathan B. Wight 40 Conclusion: It is hard to construct a “fact” in isolation from context, theory, worldview, and human judgment. © Jonathan B. Wight 41 Example from Economics The study of unemployment © Jonathan B. Wight 42 1. Where do research questions come from? (worldview, vision) Key issue: Who is paying for the research? Do research payers always ask the most important questions? What biases enter in? © Jonathan B. Wight 43 2. Model-Building * Market wage clearing model * Keynesian wage rigidity model * Marxian class conflict model (worldview, ideology, institutions) © Jonathan B. Wight 44 3. Data Collection a) How do we define the data to be collected? That is, what is “unemployment”? Any answer we give requires a judgment about why we are collecting the data and what goal its collection will serve. © Jonathan B. Wight 45 3. Data Collection b) How much data do we collect? Data is not free. There are opportunity costs of acquiring data. How much is the “right” amount? © Jonathan B. Wight 46 3. Data Collection c) Collecting the data is constrained by ethical considerations in addition to economic limitations. For example, is it possible to collect data by kidnapping people and torturing them? [Think of Hitler’s concentration camp experiments in the further of science.] © Jonathan B. Wight 47 3. Data Collection d) Collecting the data might CHANGE the data! For example, surveying households about who’s actively looking for work might stimulate someone to start searching! Asking consumers about their confidence in the economy could introduce uncertainty into their minds that didn’t previously exist! This is called the “Observer” problem, also in physics known as “Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle.” © Jonathan B. Wight 48 4. Data Analysis a) Statistical significance * Type I error * Type II error b) Economic significance © Jonathan B. Wight 49 Statistical Significance Spending on Childhood Intervention vs. H.S. Graduation Rates (after 12 yrs.) Graduation Rate 100 90 RAW DATA 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 $0 $500 $1,000 $1,500 $2,000 Per Capita Annual Spending Does spending on childhood intervention programs increase high school graduation rates? © Jonathan B. Wight 50 Statistical Significance Spending on Childhood Intervention vs. H.S. Graduation Rates (after 12 yrs.) 71 RAW DATA Graduation Rate 69 67 65 63 61 59 57 $400 $600 $800 $1,000 $1,200 $1,400 Per Capita Annual Spending Eyeballing the curves is not helpful—because changing the scale will alter the perception of slope. © Jonathan B. Wight 51 Spending on Childhood Intervention vs. H.S. Graduation Rates (after 12 yrs.) 80 REGRESSION LINE ESTIMATION Graduation Rate 75 70 65 60 Is the slope of this line bigger than zero? 55 50 $400 $600 $800 $1,000 $1,200 $1,400 Per Capita Annual Spending So we have to test statistically to see whether there is a high probability that these data reflect a rising slope. But what probability is “high enough” for certainty? © Jonathan B. Wight 52 Type I Error (false positive) – we accept the independent variable as significant when it is not. Hence we fund childhood intervention programs when really they are not effective. Type II Error (false negative) – we reject the independent variable as significant when it really is. Hence we cut off funding for childhood programs, even though they are effective. Most econometric studies select a 95% confidence level for estimating regression coefficients (5% chance of making a Type I error). This determination of what is acceptable or “scientific” level of certainty is purely judgmental, which is to say normative. Economic Significance: Moreover, even if the correlation is statistically significant, is it “economically” significant? Does it have “oomph”? © Jonathan B. Wight 53 5. Research Dissemination a) Truthtelling Why don’t scientists simply lie about their results? Example: Suppose your results don’t support your research funding agency’s agenda. Should you fabricate results so as to get more future grants? Science entails the absolute ethical judgment that “truth” matters – more than careers and money. © Jonathan B. Wight 54 5. Research Publication b) External financing c) External evaluation “Funeral by funeral, science progresses.” © Jonathan B. Wight 55 6. Economic Knowledge Research changes public policy (reform of welfare laws, changes in unemployment compensation) John Maynard Keynes: “Practical men, “who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.” © Jonathan B. Wight 56 SUMMARY Whether a researcher desires it or not -- or is even conscious of it or not -the act of carrying out positive economics entails numerous value judgments. Researchers cannot escape from making ethical choices in doing positive economics. © Jonathan B. Wight 57 “Positive” economics is a mix of: “science” and “normative values” (analytical effort and judgments) Absolute ethical standards are required of researchers (honesty, fiduciary behavior to subjects). Questions or comments? © Jonathan B. Wight 58 Lesson 6: What Should We Do About Sweatshops? Normative economics – the study of what “ought to be.” When economists analyze public policies they are engaged in ethical deliberation. Critical thinking about public policy includes an understanding of alternative moral frameworks. © Jonathan B. Wight 59 WHAT ETHICAL APPROACH IS THE SPEAKER ENDORSING? WHAT LOGICAL FALLACY DOES THE SPEAKER PROMOTE? http://www.sciencecartoonsplus.com/gallery/ethics/eth06.gif © Jonathan B. Wight 60 Answers: When the speaker says the “real world kicks in”, doesn’t he imply that the CONSEQUENCES have to be considered? Considering consequences is what consequentialists do, but they are ALSO doing ethics when they do this. So, the speaker is speaking nonsense, by implying that ethics lies OUTSIDE of consequentialism. Many economists and business people think that ethics should be kept out of the discussion—without realizing that they are already doing ethics whether they realize it or not! Remember: normative economics (e.g., analysis of welfare and consumer and producer surpluses) is a type of ethical analysis. It is ethical if you accept this method as the correct ethical approach. © Jonathan B. Wight 61 Alternative Ethical Approaches Outcomes-based ethic: focus on results Utilitarian ethics – pleasure and pain to all feeling creatures: Jeremy Bentham and J.S.Mill Economic ethics – dollar costs and benefits to consumers and producers Duty-based ethic: focus on process and rights Religious ethics – duty to divine commandments. Kantian ethics – duty to rational rules or principles (Some things are just wrong no matter how many people benefit.) Virtue-based ethic: focus on character Aristotle, Adam Smith – pursuit of excellence McCloskey – The Bourgeois Virtues: Ethics for an Age of Commerce © Jonathan B. Wight 62 Visual 6.3 Approaches to Sweatshops © Jonathan B. Wight 63 What Should We Do About Sweatshops? Options: 1. International Treaty 2. Markets and Monitoring 3. Take No Action Activity 6.3 © Jonathan B. Wight 64 Conclusion 1. Economic theory does NOT provide the final answer to complex public policy questions. 2. Critical thinking implies students must make decisions for themselves. 3. Critical thinking can be cultivated: * by focusing on the normative elements of good science; and * by expanding the moral framework of analysis. © Jonathan B. Wight 65