HUMR5120

Substantive Rights

Reservations, Limitations

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Reservations, Limitations and

Derogations

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Eide, pp 407-421

Ovey, pp 218-240, 432-438, 439-450, 451-458

Cases for reading:

McCann and Others v. The United Kingdom

Refah Partisi v. Turkey

Consult the Greek case, 1969

Added Belilos v. Switzerland

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Reservations, Limitations and

Derogations

•

•

•

•

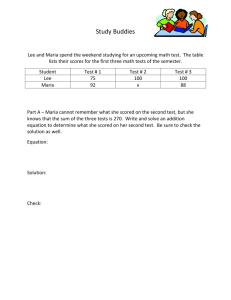

In accordance with international human rights law

there are essentially three ways in which the

State may limit or restrict the scope of its

obligations:

Reservations to treaties

Express limitations to rights

Derogations from rights

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Reservations, Limitations and

Derogations

• A balance of interests

– Society v. individual

• Universality of human rights?

– Which universality?

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Reservations (1)

• International law:

• Article 19 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of

Treaties (VCLT)

• ICCPR – no provision

– Therefore – Art. 19 © VCLT ”object and purpose of the treaty”

• Art. 2 Second Optional Protocol

– Death penalty in time of war

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Article 19 VCLT –

Formulation of reservations

• A State may, when signing, ratifying, accepting,

approving or acceding to a treaty, formulate a

reservation unless:

– (a) the reservation is prohibited by the treaty;

– (b) the treaty provides that only specified reservations, which do

not include the reservation in question, may be made; or

– (c) in cases not failing under subparagraphs (a) and (b), the

reservation is incompatible with the object and purpose of the

treaty.

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Reservations (2)

•

Art. 57 ECHR

1.

2.

and

1.

2.

•

Only if law in force is not in conformity with the ECHR

Only if not of a general character

Only if a short description of the law is provided

Only if it is made at time of signature or depositing the

ratification

Art. 19 © VCLT

–

Only if not contrary to the object and purpose of the treaty

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Supervision of validity/compatibility

• The ECHR has competence:

– That the Court has jurisdiction is apparent from Articles 45 and 49

(art. 45, art. 49) of the Convention, which were cited by the

Government, and from Article 19 (art. 19) and the Court’s case-law

(see, as the most recent authority, the Ettl and Others judgment of

23 April 1987, Series A no. 117, p. 19, § 42). (See Belilos v.

Switzerland (Appl. 10328/83), Judgment of 29 April 1988, para. 50)

• Human Rights Committee – competent (CCPR General

Comment 24, para. 18)

• Cf. Art. 20.4 VCLT

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Criteria under Art. 57 ECHR

• A reservation may not be ”general” (see Belilos v. Switzerland,

p. 26, para.55):

• “By “reservation of a general character” ... is meant in particular

a reservation couched in terms that are too vague or broad for it

to be possible to determine their exact meaning and scope. ...

Article 64§1 requires precision and clarity.”

• A short description of the law is required it contributes to “legal

certainty”

•

T he “brief statement of the law concerned” both constitutes

an evidential factor and contributes to legal certainty. The

purpose of Article 64 § 2 is to provide a guarantee ... that a

reservation does not go beyond the provisions expressly

excluded by the State concerned.( Belilos, para. 59)

– Cf. Chorherr v. Austria (Application no. 13308/87), Judgment 23 August

1993, Ser. A., No. 266-B

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Criteria under ECHR

•

•

•

Excluded:: Article 15-18 ECHR and Supervisory mechanisms

See Loizidou v. Turkey (15318/89), Judgment 23 March 1989, para

75

If, as contended by the respondent Government, substantive or

territorial restrictions were permissible under these provisions,

Contracting Parties would be free to subscribe to separate regimes

of enforcement of Convention obligations depending on the scope

of their acceptances. Such a system, which would enable States to

qualify their consent under the optional clauses, would not only

seriously weaken the role of the Commission and Court in the

discharge of their functions but would also diminish the effectiveness

of the Convention as a constitutional instrument of European

public order (ordre public). Moreover, where the Convention permits

States to limit their acceptance under Article 25 (art. 25), there is an

express stipulation to this effect (see, in this regard, Article 6 para. 2 of

Protocol No. 4 and Article 7 para. 2 of Protocol No. 7) (P4-6-2, P7-72).

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Criteria under ECHR

– Loizidou v. Turkey (15318/89), Judgment 23 March 1989, para 75

cont.

• In the Court’s view, having regard to the object and

purpose of the Convention system as set out above,

the consequences for the enforcement of the

Convention and the achievement of its aims would

be so far-reaching that a power to this effect should

have been expressly provided for. However no such

provision exists in either Article 25 or Article 46 (art.

25, art. 46).

• The present amended ECHR: Art. 32 ECHR –

mandatory jurisdiction

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Criteria for incompatibility with the

ICCPR

• Art. 19.(c) VCLT

• The reservation is incompatible with the object and

purpose of the treaty.

• Offending peremptory norms (customary)

– Ex: torture; thought, conscience and religion; denial of minority

rights to culture, language or religion… self-determination

• However, not necessary non-derogable

• No reservation to Art. 2.3 or 40 ICCPR

• Not widely formulated reservations which essentially render

ineffective all Covenant rights

• (CCPR General Comment 24, paras. 8-12)

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Reservations separated from the rest

of the treaty

• Loizidou v. Turkey (15318/89), Judgment 23 March

1989, para. 97.

• Even considering the texts of the Article 25 and 46

(art. 25, art. 46) declarations taken together, it

considers that the impugned restrictions can be

separated from the remainder of the text leaving

intact the acceptance of the optional clauses.

• CCPR General Comment 24, para. 20

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Limitations

•

•

•

•

Balance of legitimate interests

No time limitations

Strict interpretation

Must be necessary in a democratic society – “margin

of appreciation”

• Proportionality

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Limitations are permissible

ECHR

ICCPR

Art. 8

Art. 17, 23

Art. 9

Art. 18

Art. 4.2 ICCPR Freedom of

religion or

belief

Art. 10

Art. 19, 20

Art. 4, 4.a)

Freedom of

expression

Art. 11

Ar. 21, 22

Art. 8.1a,c; 8.2

ICESCR

Freedom of

assembly and

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Other prov. of

relevance

Rights and

freedoms

Private and

family life

Limitations are permissible

Art. 2 Protocol

4

Art. 12

Freedom of

movement/resi

dence

Art. 1.2

Protocol 7

Art. 13

Expulsion of

aliens

Art. 16

Art. 1 Protocol

1

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Cf. Art. 25

ICCPR

Political activity

of aliens

Right to

property

Limitations are permissible

• Art. 4 ICESCR

• “.., the State may subject such rights only to such

limitations as are determined by law only in so far as

this may be compatible with the nature of these

rights and solely for the purpose of promoting the

general welfare in a democratic society.”

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Strict interpretation

• “It follows from the nature of paragraph 2 of article 10 as an

exception clause that this provision must, according to a

universally accepted rule, be strictly interpreted. This is

especially true in the context of the Convention the object and

purpose of which is to safeguard fundamental human rights.

Strict interpretation means that no other criteria than those

mentioned in the exception clause itself may be at the basis of

any restrictions, and these criteria, in turn, must be understood

in such a way that the language is not extended beyond its

ordinary meaning (cf. paragraph 44 of the Court’s judgment of

21 February 1975 in the Golder case ...)”

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Strict interpretation

•

“In the case of exception clauses such as … the

principle of strict interpretation meets certain

difficulties because of the broad meaning of the

clause itself. It nevertheless imposes a number of

clearly defined obligations on the authorities of the

High Contracting Parties …” (Sunday Times case,

Report of the Commission, B. 28, paras. 194-195)

1. Proportionality of interference in relation to a

legitimate aim

2. Only a minimum interference to secure the aim

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Permissible limitations

•

Criteria:

1. Lawful: “in accordance with the law” or “prescribed

by law”

2. Legitimate: aims listed in the provisions

3. “Necessary in a democratic society”

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Lawful:

• “in accordance with the law” or “prescribed by law”

• What s considered to be “law” ?

• “common law” and administrative regulations and

international treaties. (See The Sunday Times, Judgment of 26

April 1979, A.30, p. 30; Barthold, Judgment of 25 March 1985, A. 90,

p. 21-22, Slivenko v. Latvia, (App. 48321/99), Judgment 9 October

2003 (Grand Chamber))

• “clear, accessible, precise and foreseeable” without

being “excessive rigidity” (The Sunday Times, Judgment of 26

April 1979, A.30, para. 49)

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Legitimate aims as listed in the

provisions

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

“national security”

“public safety”

“public order”

“prevention of crimes”

“morals”

“health”

“the reputation of others”

“the protection of the rights of others”

“the economic welfare of the country”

“the prevention of disclosure of information received in

confidence”

• “the guaranteeing of the impartiality of the judiciary”

• “the prevention of disorder and crime”

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Necessary in a democratic society

• “not synonymous with “indispensable” … neither has it the

flexibility of such expressions as “admissible”, “ordinary”,

“useful”, “reasonable”, or “desirable”.

• a “pressing social need”, acc. to the ECHR

– proportionality is required in relation to the stated aim

• The ECHR refers to the State’s “margin of appreciation”

– to a larger or lesser extent depending on the nature of the rights or on the

balancing of the competing claims. See Ovey and White, pp. 232-239.

• See Handyside v. the UK, Judgment of 7 December 1976, A.

24, paras.48-49; Silver, Judgment of 25 March 1983, A. 61,

paras. 26, 48, 97-98.

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Derogations

• A derogation measures are only allowed in

exceptional circumstances and should be of

temporary nature.

• Only in “difficult situations” when the “life of the

nation” is at stake.

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Derogations

•

•

•

•

•

•

Exceptional circumstances

Non-derogable rights

Strictly required – proportionality

Temporary

Procedure – international and domestic

Applicable law during emergencies: Humanitarian

law and international criminal law and parts of

international human rights law

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Derogations – some treaties

• Art. 4 ICCPR

• Art. 2.1 Second Optional protocol

– reservation for war time

• Art. 15 ECHR

• Art. 3 ECHR Protocol 6

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

Four questions

1.

2.

3.

4.

When?

How?

For how long?

Lawful or not?

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

1. WHEN?

1.

2.

War and state of emergency

Threat to the existence of the State

•

•

Lawless case (ECHR):

“an exceptional situation or crisis of emergency which affects the whole population

and constitutes a threat to organised life in the community of which the State is

composed”

(See Commissionen REPORT, 19 Dec 1959, B.1 (1961), p.. 82, and, Judgment of 1 July

1961, P. 56)

In Greece v. the UK the Commission and the Court developed the criteria for scrutiny:

It must be actual or imminent.

Its effects must involve the whole nation.

The continuance of organised life in the community must be threatened

The crisis or danger must be exceptional, in that the normal measures or

restrictions, permitted by the Convention for the maintenance of pubic safety, health

and order, are plainly inadequate.

(See report of the Commission, 5 November 1969, YB XII (1969), p. 72 and pp.. 76, 100

(also pp. 45-71)

•

•

1.

2.

3.

4.

•

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

2. HOW?

• 2.1 Non-derogable rights:

Derogations may neither be contrary to other

obligations under international law nor to the rights

which are listed as “non-derogable” under Art 15 of

the ECHR or Article 4 of the ICCPR. (for nonderogable under international law, see Human

Rights Commttee Gen. Comment 29, on states of

emergency)

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

2. HOW?

•

2.1 Non-derogable rights CONT.:

•

A number of rights are non-derogable according to Art. 4

ICCPR and Art. 15 ECHR

Art. 15 ECHR:

•

–

–

–

–

•

Art.2 (life), Art. 3 (torture), Art. 4.1 (slavery), art.7 (no punishment without

law)

No exceptions to Art. 3 and Art.4.1.

Qualified in relation to life,”lawful acts of war”, see also Protocol 6, Arts. 2

and 3

NB. The content of Art. 6 ICCPR and Art. 2 ECHR should be compared

Non-derogable rights in Art. 4 ICCPR also include:

–

–

Art 11 (prison upon non-fulfilment of contractual obligation) and

Art 18 (thought, concience and religion)

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

2. HOW?

• 2.b. Non-discrimination:

– Art. 4.1 “on the grounds of race, colour, sex, language, religion and social

origin”.

– However, art 14 ECHR is an integral part of all rights (Ireland v. the UK, s.

86-88, para.228-232 )

• 2.c Derogations may not contradict other human rights

obligations, whether contained in national or international law,

see Art. 53 ECHR

• Take note of the obligations under ICESCR, international

humanitarian law and international criminal law . See Eide, pp.

407-421

• States which are bound by both the ECHR and the ICCPR

Brannigan och McBride, Judgment of 26 May 1993, A. 258-B,

s.56-57; Lawless, P. 60, Ireland v. the UK, P.84

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

2. HOW?

• 2.d. Necessary in a democratic society

• In relation to the “margin of appreciation”

– Ireland v. the UK, Judgment of 18 January 1978, A. 25, p. 78-79, 81-82,

92-93; Lawless, Merits, Judgment of 1 July 1961, A. 3, p. 55-56.)

– See also Brannigan och McBride, Judgment of 26 May 1993, A. 258-B, p.

29, 33, 40-42 for critique of the wide margin of appreciation

• Art. 15 ECHR: Measures should be “strictly required” in relation

to the situation,

– Lawless, Judgment, s. 58, para. 36, Ireland v. the UK, Judgment, s. 8081, para. 212, Brannigan and McBride, s.53-54, para. 56-60..

• 2.e. Proportionality

• “the rule of law”,

– Lawless, s.58, para.36; Ireland v. the UK, p. 81, para. 212; Brannigan v.

McBride, p. 53-54, para. 56-59.

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

3. FOR HOW LONG?

• 3.a Temporary

• Brannigan and McBride, p. 52

• The validity of the derogation cannot be called into

question for the sole reason that the Government

had decided to examine whether in the future a way

could be found of ensuring greater conformity with

the Convention obligations. Indeed, such a process

of continued reflection is not only in keeping with

Article 15 para. 3 which requires permanent review

of the need for emergency measures but is also

implicit in the very notion of proportionality.

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008

4. LAWFUL or NOT?

•

4.a Requirements in Article 4 of ICCPR and Article 15 of the ECHR

And in the domestic legal order

–

•

4.b A balance between State discretion and the supervisory organs’

competence

–

–

•

Brannigan och McBride, Judgment of 26 May 1993, A. 258-B, s.56-57; Lawless, p.

60, Ireland v. the UK, p.84

The requirements for a permissible derogation under ECHR and the ICCPR are tested

by the Court or the Committee despite the recognized margin of appreciation of states

to determine their situation and which necessary measures to adopt.

See Ireland v. the UK, Judgment of 18 January 1978, A. 25, p. 78-79, 81-82, 92-93;

Lawless, Merits, Judgment of 1 July 1961, A. 3, p. 55-56. and cf. Gen. Comment 29,

on states of emergency, para. 5)

“Margin of appreciation”

–

–

Brannigan och McBride, Judgment of 26 May 1993, A. 258-B, p. 29, 33, 40-42)

Human Rights Committee’s General Comment Comment No.29, on states of

emergency.

Maria Lundberg, NCHR, 13 November 2008