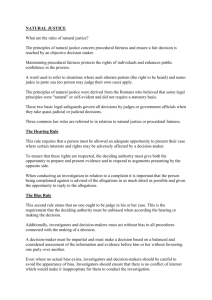

Procedural Fairness

advertisement

Chapter 8 in Mullan Diana Morris April 8, 2009 THE CHAPTER AT A GLANCE Mullan begins explaining procedural fairness rights by justifying oral or in person hearings. II. Then proceeds with outlining relevant constitutions I. I. II. Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (CCRF) Canadian Bill of Rights III. Common law cases where the principle of “procedural fairness” rights were not applied in the original decisions. I. II. III. Cooper v. Board of Works for Wandsworth District Board of Education of the Indian Head School Division No.19 of Saskatchewan v. Knight. Nicholson v. Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Board of Commissioners of Police Justifying administrative process Justification of oral or in-person hearings= procedural fairness. • There is a sense that these types of hearings will produce better and fairer outcomes because plaintiff’s can hear all the evidence and listen to all the various perspectives on a question. •Also, affected parties would be more likely to accept the outcome when they participate in a hearing versus a decision being made in secret by faceless or nameless bureaucrats. Their participation in the decision making process would involve being able to confront the actual decision maker. This also contributes to the belief in the participation in a democratic process. •There is also an accountability aspect. Open courtrooms force the decision maker to be more careful and reflective in the ways they act and in the conclusions they reach because they are subject to public scrutiny and criticism. Sources of Process Claims: Constitutional and QuasiConstitutional Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (CCRF) According to Mullan, the CCRF is the clearest source of constitutional protection for procedural claims in Canada because it enshrines a right to “the fundamental principle of justice”. S. 7 and S.11 of the Charter are subject to legislative override created by s. 33(1) notwithstanding clause. Therefore, there is a justifiable reason in a free and democratic society for not providing the benefit of the “principles of fundamental justice” when “life, liberty and security of the person” is at stake. Relevant legislation 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Section 7 Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice. Section 11 Any person charged with an offence has the right (a) to be informed without unreasonable delay of the specific offence; (b) to be tried within a reasonable time; (c) not to be compelled to be a witness in proceedings against that person in respect of the offence; (d) to be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law in a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal; (e) not to be denied reasonable bail without just cause; (f) except in the case of an offence under military law tried before a military tribunal, to the benefit of trial by jury where the maximum punishment for the offence is imprisonment for five years or a more severe punishment; (g) not to be found guilty on account of any act or omission unless, at the time of the act or omission, it constituted an offence under Canadian or international law or was criminal according to the general principles of law recognized by the community of nations; (h) if finally acquitted of the offence, not to be tried for it again and, if finally found guilty and punished for the offence, not to be tried or punished for it again; and (i) if found guilty of the offence and if the punishment for the offence has been varied between the time of commission and the time of sentencing, to the benefit of the lesser punishment. Section 33 (1) Parliament or the legislature of a province may expressly declare in an Act of Parliament or of the legislature, as the case may be, that the Act or a provision thereof shall operate notwithstanding a provision included in section 2 or sections 7 to 15 of this Charter. Sources of Process Claims: Constitutional and QuasiConstitutional (Cont’d) The Canadian Bill of Rights and Various Provincial Bills of Rights The principal provision of this Bill that pertain to procedural claims within the administrative process are; s. 1(a) provides a “due process” guarantee when life, liberty, security of the person and enjoyment of property are at stake. s. 2(e) ensures, “the right to a fair hearing in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice” whenever a person’s “rights and obligations” are being determined. NOTE: the difference between the Bill of Rights (BR) and the Charter is that the B.R provides a useful source of constitutionally protected procedural rights in the federal domain not covered by the Charter. Examples of Common Law I. Cooper v. Board of Works for Wandsworth District Background of case- The Wandsworth District Board tore the plaintiff’s (Cooper) house down without notice, because he had failed to comply with The Metropolis Local Management Act. The Act required the plaintiff to notify the board seven days before starting to build the house. Cooper argued that even though the board had the legal authority to tear his house down, no person should be deprived of their property without notice. Cooper explains that the strongest claim for a hearing in the face of legislative silence is in cases where the claimant’s property or physical person is being affected by the decision. No man is to be deprived of his property without having the opportunity to be heard. Common law cont’d II. Board of Education of the Indian Head School Division No.19 of Saskatchewan v. Knight ISSUE- Knight’s position as superintendent of a school board was held at pleasure. The rationale for dismissal was that it was a “pleasure” position. He was removed for non personal reasons. Nonetheless, he was entitled to a degree of procedural fairness. Knight should have been awarded the opportunity to try to persuade the board to change their mind. Requiring a hearing would impose better controls and ensure greater public accountability for their exercise. Supreme Court of Canada, justice L’Heureux-Dube J decided that there was a general right of procedural fairness, autonomous of the operation of any statue. In this case, she considered whether the plaintiff’s procedural entitlements had been excluded by the legislation or by contrast. She believed that procedural fairness claims could withstand specific legislative exclusion. Common law cont’d III. Nicholson v. Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Board of Commissioners of Police (landmark reform of administrative law) ISSUE- Nicholson, a probationary police officer who was employed for a period of 18 months and was later dismissed from his job with no reason given and no opportunity for a hearing. According to relevant regulation provided that chiefs of police and other police officers and constables are entitled to “hearing” and an appeal against dismissal. However, this does not apply to individuals who have less than eighteen months of service (probation). Mullan queries, did this case present two levels of requirements (1) natural justice applicable to judicial and quasi-judicial functions and (2) procedural fairness applicable to purely administrative functions? According to the principles of “procedural fairness” Nicholson should have been given the opportunity to respond to criticism of his performance before he was dismissed, either orally or in writing. The Supreme Court decided that Nicholson should have been given the opportunities available under the procedural fairness principle.