The Crisis of Pain in America

advertisement

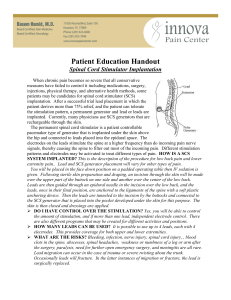

Our Role in the Management of Chronic Pain Speaker/consultant for St. Jude’s; also receiving research grants Speaker/stock holder for Insys Therapeutics Speaker/consultant for Central Avenue Pharmacy Confidenti al. For Internal Use Only. Do Not Distribute Understand the impact that pain, specifically chronic pain, has on our society Discuss pharmacological approach to pain management Review neuromodulation as it pertains to interventional pain management Determine when interventional approaches to pain management are appropriate Discuss surgical implants for pain management BURDEN OF CHRONIC PAIN IN THE UNITED STATES Affects 100 million Americans (more than heart disease, cancer and diabetes combined)1 Costs society up to $635 billion annually1 Associated with 40 million doctor visits annually2 Results in 515 million lost workdays annually2 40% of all work absences are related to low back pain3 1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. 2011. 2. Rich SJ. Adv Stud Pharm. 2009;6(4):115-119. 3. Manchikanti L, et al. Pain Physician. 2009;12:699-802. 4 Cost in billions of dollars (2010) CHRONIC PAIN IS AMONG THE TOP COSTLY CONDITIONS IN THE UNITED STATES $700 $600 $500 $400 $300 $200 $100 $0 Chronic pain Heart disease Cancer 1 Diabetes 1 Obesity 1 2 1 1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. 2011. 2. Wang Y, et al. Obesity 2008;16(10):2323-2330. 5 The National Health Expenditure reached $2.5 trillion in 2009 and is expected to reach $4.5 trillion in 20191 $US billions $5.0 $4.0 $3.0 $2.0 $1.0 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 The Affordable Care Act includes measures to reduce waste in health care spending, including Medicare and Medicaid fraud and abuse, resulting in an anticipated savings of $7 billion over 10 years2 1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditure Projections 2009-2019. Accessed April 23, 2014. 2. Orszag PR, Emanuel EJ. N Engl J Med. 2010;363;7:601-603. 6 In addition to the significant economic burden1 and negative impact on quality of life,2 untreated chronic pain is associated with physical and psychological complications3-6 35% of chronic pain patients vs 4.6% of the general study population Depression3 Suicide ideation lifetime prevalence in chronic pain patients, ~20% vs 13.5% in the general population Suicide4 39% of chronic pain patients vs 21% of the general population Hypertension5 53% of chronic pain patients vs 3% of pain-free controls Insomnia6 62.7% of patients with low back/neck pain vs 56.5% of the general population Overweight/obese9 20-24% of chronic pain patients vs 3.8% of the general population Opioid misuse/abuse7,8 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. 2011. Reid KJ, et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:449-62. Miller LR, Cano A. J Pain. 2009; 10(6):619-627. Tang NKY, et al. Psych Med. 2006;36:575-586. Bruehl S, et al. Clin J Pain. 2005;21(2):147-153. Tang NKY, et al. J Sleep Res. 2007;16:85-1695. Suicide attempts lifetime prevalence in chronic pain patients, 5-14% vs 4.6% of the general population 7. 8. 9. Sullivan MD, et al. Pain. 2010;150(2):332-339. Behavioral Health Coordinating Committee Prescription Drug Abuse Subcommittee. Addressing prescription drug abuse in the United States: current activities and future opportunities. Accessed June 4, 2014.. Strine TW, Hootman JM. Arthritis Rhem. 2007;57(4):656-665. 7 THE BENEFITS OF SENDING PATIENTS TO PAIN SPECIALISTS Goals of Pain Physicians Treating Chronic Pain Types of Pain Treated by Pain Physicians Establish accurate diagnosis Improve patient care1 Chronic back, neck, shoulder, trunk, and limb pain Increase activity levels2 Neuropathic pain Improve functional life activities2 Post-surgical pain syndromes Reduce disability, return patients back to work2 Failed back surgery syndrome Decrease overutilization of opioids2 Degenerative disc disease Reduce emotional distress, such as depression and anxiety2 Cancer pain Arthritis Complex regional pain Decrease the use of medical resources2 1. Davies HTO, et al. J R Soc Med. 1994;87(7):382-385. 2. Clark TS. BUMC Proceedings. 2000;13:240-243. 8 A Changing Paradigm for the Management of Chronic Pain The historical approach to chronic pain treatment involves sequential testing of multiple analgesics, with interventional therapies (eg, spinal cord stimulation) as “last resort”1 In a new, simplified, patient-centric approach, interventional therapies are earlier in the treatment continuum2 New Approach to Chronic Pain Treatment Aggressive Care (Step 3) Less Less Conservative Conservative -Moderate Care (Step 2) Chronic opioid maintenance Intrathecal therapy Surgical intervention Conservative Care (Step 1) Physical therapy OTC pain medications Psychological therapy NSAIDs 9 Injection therapies† Neuroablation Low dose opioids Low-dose Spinal cord stimulation TENS Neurolysis Spinal cord stimulation Thermal procedures Neurolysis Thermal procedures CONFIDENTIAL – For Internal Use Only. Do Not Distribute US-2001416 A EN (06/14) 1. Kaplan R. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:62-63. 2. Poree L, et al. Neuromodulation. 2013;16(2):125-141. MORTALITY AND COSTS RELATED TO OPIOID MISUSE AND OVERDOSE IN THE UNITED STATES The percentage of drug overdose deaths related to opioids doubled from 1999 to 20101 Opioid overdose is responsible for more than 16,000 deaths annually1 Non-medical opioid use is associated with $75.2 billion in insurance costs per year2 Rate of Opioid Overdose Deaths (per 100,000)1 6 5 Rate 4 3 2 1 0 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Year http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/overdose/hhs_rx_abuse.html 1. Behavioral Health Coordinating Committee Prescription Drug Abuse Subcommittee. Addressing prescription drug abuse in the United States: current activities and future opportunities. Accessed June 4, 2014. 2. Coalition Against Insurance Fraud. Prescription for peril: how insurance fraud finances theft and abuse of addictive prescription drugs. Accessed April 22, 2014. 10 RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH OPIOID THERAPY Overdose-related deaths1 16,651 deaths/year Non-medical use rate1 3.8% of the US population Insurance costs of non-medical use2 $72.5 billion/year Constipation/bowel dysfunction3 ~41% of chronic opioid users Endocrine effects (opioid-induced androgen deficiency4) Affects ~5 million men taking opioids for chronic pain in the US Immunologic challenges5 May be associated with immunosuppression Ataxic breathing during sleep6 ~70% of chronic opioid users 1. Behavioral Health Coordinating Committee Prescription Drug Abuse Subcommittee. Addressing prescription drug abuse in the United States: current activities and future opportunities. Accessed June 4, 2014. 2. Coalition Against Insurance Fraud. Prescription for peril: how insurance fraud finances theft and abuse of addictive prescription drugs. Accessed April 22, 2014. 3. Kalso E , et al. Pain. 2004;112:372-80. 4. Colameco S, Coren JS. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109:20-24. 5. Ballantyne JC. South Med J. 2006;99:1245-1255. 6. Walker JM, et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5):455-461. 7. Taylor RS, et al. Spine. 2005;30(1):152-160. 8. Frey ME, et al. Pain Physician. 2009;12:379-397. 11 Long-Term Pain Affects Most of Your Patients (Peter D. Hart Research Associates) 3 out of 4 Americans have experienced chronic or recurring pain or have a family member who has experienced such pain Almost 62% of pain sufferers have had their pain for a year or more A majority of adults (57%) have experienced chronic or recurring pain, including 54% of adults aged 18–34 Types and Definitions of Pain Acute pain Accompanies tissue injury or pathology Comes on quickly and lasts a short time Varies in severity and intensity Chronic pain Continues a month or more beyond usual recovery period Goes on for months or years due to a chronic condition Difficult to define onset Types and Definitions of Pain Nociceptive pain Caused by irritation to special nerve endings (nociceptors) Can be dull or sharp Can be mild or severe Neuropathic pain Caused by a malfunction of the nervous system The result of injury, disease, or trauma Can be sharp, intense, and constant Can be dull, aching, and throbbing Failed Back Surgery Syndrome Back and/or leg pain that recurs or persists following seemingly successful back surgery Surgical goals not met Patient goals not met Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy (Belgrade) Simultaneous decreased sensation in the distal extremities in patients with diabetes Manifested by loss of sharp vs. light touch discrimination, numbness, and tingling in combination with burning pain Intrathecal Pump as a therapy for chronic, intractable pain. Significant decrease in oral opioid need. Trial can be single injection or epidural catheter. Combination of local anesthetics, alpha-blockade, and/or opioids create synergistic effects. New medications (ie. ziconitide – calcium channel blocker) create new opportunities and abilities to control chronic pain. Pump can be accessed easily and effectively programmed to control pain medication in microliters. SCS as an Advanced Treatment for Pain History of Neurostimulation (Glindenberg) One of the earliest uses of electricity in medicine was for pain relief. Around 15 A.D., Scribonius reported that a torpedo fish could be used to apply an electrical charge to patients to relieve pain. Courtesy of Dr. Thomas Simopolous, Boston, MA Neuromodulation Devices (Electrical Stimulators and Drug Pumps) Allow the delivery of very small, precise doses of electricity or drugs directly to targeted nerve sites. What is Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS)? Tenets of SCS Comprehensive trial Customizable system components Optimized efficiency in programs and design Team approach to patient care SCS Phases Trial period Permanent implant Advantage of an SCS Trial One big advantage of SCS over other pain management therapies is that it can be tested on patients before an SCS device is permanently implanted The trial gives the pain management physician important information for determining which of the two SCS systems, conventional or rechargeable, is appropriate for a specific patient About the SCS Trial A short outpatient procedure during which the physician places one or more leads in the space over the spinal cord The patient is generally awake during the procedure so that he or she can provide feedback to the physician regarding exact placement A lead connects to a device that can be worn on a belt. The device will contain a variety of programs About the Trial System Trial Lead Trial Cable Trial Generator/Programmer Lengths of Trials Short-term trials 1 to 3 days 3 to 5 days Long-term trials 7 to 10 days Trial Diary Can be used as a guide to determine the device type and the parameters that were favored during the trial Helps patients get involved in their therapy Patient/Device Criteria Conventional IPG Rechargeable IPG Power requirements Low to moderate Moderate to high Frequency requirements Low Low to moderate Disease state Stable Likely to progress Coverage needs (contacts/leads) 8 contacts on 1 or 2 leads 8 or 16 contacts on 1-4 leads Compliance (motivation and ability) Requires very little interaction High—due to recharging protocol Competence (physical or mental) Appropriate for all levels Higher level required Skin sensitivity Patients with high sensitivity Patients with moderate to low sensitivity Implant size Moderate to large sizes Small to moderate size Implant longevity 2-7 years 5-10 years Patient interface Easier to use Requires management Lead Family The 5-Column Paddle Lead Designed to provide greater lateral electrode coverage and nerve fiber selectivity Provides five columns of the smallest electrodes on the market, for greater specificity and programming flexibility Lateral Electrode Coverage 40% of patients have a spinal cord 1-2 mm off midline (Holsheimer) 2 mm *Approx. 4.5 mm 2 mm 8.5 mm of lateral electrode coverage needed *At T9 Improved Lateral Current Steering Actual Clinical Results Certain programming configurations on the 5-column paddle lead may be able to isolate paresthesia within the dermatome itself. (Feler) The diagrams above depict actual patient-reported stimulation effects with a 5-column paddle lead. SCS Studies Reduction in pain Author No. Patients Follow-Up Results Kumar 410 8 years 74% had ≥50% relief North 19 3 years 47% had ≥50% relief Barolat 41 1 year 50%-65% had good/excel. relief Van Buyten 123 3 years 68% had good/excel. relief Alò 80 30 months (2.5 years) Mean pain scores declined from 8.2 at baseline to 4.8 Cameron 747 up to 59 mos. 62% had ≥50% relief or significant reduction in pain scores SCS Studies Reduction in medication Author No. Patients Follow-Up Results North 19 3 years 50% reduced their med use Van Buyten 123 3 years as a group reduced the medication use by >50% Cameron 766 up to 84 mos. 45% reduced their med use Taylor 681 n/a 53% no longer needed analgesics SCS Studies Improvement in daily activities Author No. Patients Follow-Up Results Barolat 41 1 year As a group, significant improvements in function and mobility North 19 3 years As a group, improvements in a range of activities SCS Studies Return to work Author No. Patients Follow-Up Results Van Buyten 123 3 years 31% returned to work Taylor 1133 n/a 40% returned to work Dario 23 3 years 35% returned to work Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) SCS can be used to manage neuropathic pain that arises from: CRPS (Complex Regional Pain Syndromes I and II) Peripheral neuropathy (Diabetic, Post-Chemo, Idiopathic) SCS can be used in the treatment of pain, numbness, and circulatory deficits with associated small-fiber peripheral neuropathy (SFPN)— with or without a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (DM). Twenty-five percent of Americans are either diabetic or pre-diabetic (20 million and 60 million, respectively). SFPN is a significant comorbid process, with onset of DM occurring at a mean of 5 years after diagnosis of SFPN, with a range of 3 months to 20 years. This suggests patients may have SFPN in the absence of diagnosed DM. SCS treatment have been shown to be successful in providing >70% pain relief in over 80% of patients with pain attributable to SFPN. 52% reported significant reduction in medication usage. 90% of patients had reversal of sensory loss. Whether this is permanent or is due to continuous SCS in unclear. Trophic change improvement with increased circulation associated with SCS has also been well documented. However, to our current knowledge, reversal of sensory loss in SFPN patients from SCS has not been well-studied. Ischemic/Neuropathic Limb Pain Primary erythromelalgia or Mitchell’s disease is a rare neurovascular condition causing severe neuropathic pain. Often times, treatment for this rare condition is difficult, and can involve neuropathic pain medications, sodium channel blockers, lumbar sympathetic blocks, and spinal interventions. Although peripheral neuropathy has been well studied and treated with spinal cord stimulation, using it for treatment of erythromelalgia is novel. Now… For the FUN STUFF!!! OFF-LABEL USE of the Spinal Cord Stimulator Intractable, chronic, tension/cluster/ migraine/sinus headaches / Occipital Neuralgia/ Temporal Arteritis Chronic headache disorders are among the most debilitating medical conditions worldwide with an estimated prevalence of 47% of all adults having suffered at least one episode of headache in the past 12 months. 10% of people are affected by migraine alone. Up to 4% of the entire world’s adult population suffer from headaches for 15 days each month! (Data from the WHO, updated October, 2012: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs277/en/) These headache states are often refractory to conventional drug therapy. An emerging treatment for these patients in whom medical management is insufficient is the implantation of subcutaneous electrodes. Sacral nerve stimulation can be a successful treatment for chronic Pelvic, Perineal, Rectal, Post-Radiation Prostitis pain. In addition, it is a viable therapeutic option for patients with pelvic pain that have failed spinal cord stimulation trials with lead placement in the thoracic epidural space. Angina Pectoris / Thoracic Chest Wall Pain MORE off-label use of the SCS: • Trigeminal Neuralgia/Facial Pain/TMJ Syndrome • Post-Herpetic Neuralgia (PHN) • Neck/thoracic pain with/without cervical/thoracic radiculopathy • Phantom limb pain • Hyperhidrosis • Neurogenic Bladder Chronic Abdominal Pain / Irritable Bowel Syndrome Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a disorder that leads to debilitating symptoms including abdominal pain and cramping and changes in bowel movements affecting approximately 1 in 6 people. As causes for this condition continue to evolve, studies have linked visceral hypersensitivity and spinal nociceptor hyper excitability between the gastrointestinal system and nervous system. The technical goals of electrical stimulation for pain management have been to mask the perception of pain with stimulation-induced paresthesia by disrupting pain signaling to the brain as well as determining what drugs can be co-administered to enhance analgesia. A more recent focus has been the optimization of electrical parameters for treating neuropathic pain. Few studies have examined the modulatory effect of an electrical field applied near the spinal cord on gene expression. More recently, studies are showing that SCS has the ability to modulate both pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression, particularly in interleukin-1ß (IL-1ß), interleukin-10 (IL-10), IL-6, and the glia activation marker GFAP, with increasing current. This fosters a better understanding of the mechanism behind SCS-induced analgesia. Future of Neuromodulation: Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation Vagus Nerve Stimulation (for Epilepsy… or… ??Weightloss??) Burst waveform stimulation High frequency stimulation BONUS STIM???!!! References Aló K, Yland M, Charnov, J, Redko V. Multiple program spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of chronic pain: follow-up of multiple program SCS. Neuromodulation. 1999;2(4):266 272. Arnst, C. Conquering pain: new discoveries and treatments offer hope. Business Week. Available at: http://www.businessweek.com/1999/99_09/b3618001.htm. Accessed January 11, 2009. Barolat G, Oakley JC, Law JD, North RB, Ketick B, Sharan A. Epidural Spinal Cord Stimulation with a Multiple Electrode Paddle Lead is Effective in Treating Intractable Low Back Pain. Neuromodulation. 2001;4:59-66. Belgrade, Miles J; Cole, B. Eliot; McCarberg, Bill H. McLean, Michael J. Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: Case Studies. April 2006;81(4l,suppl):S26-S32. Cameron T. Safety and Efficacy of Spinal Cord Stimulation for the Treatment of Chronic Pain: A 20-Year Literature Review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;100(3):254-267. Dario A, Fortini G, Bertollo D, Bacuzzi A, Grizzetti C, Cuffari S. Treatment of Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. Neuromodulation. 2001;4:105-110. Gildenberg PL. History of electrical neuromodulation for chronic pain. Pain Medicine. 2006;7(S1):S7-S13 Kumar K, Hunter G Demeria D. Spinal Cord Stimulation in Treatment of Chronic Benign Pain: Challenges in Treatment Planning and Present status, a 22-Year Experience. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:481-496. References Feler C, Garber J. Selective dermatome activation using a novel five-column spinal cord stimulation paddle lead: a case series. Poster presented at: Annual meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society; December 3-5, 2009, Las Vegas, NV. Hill, Catherine L., Gill, Tiffany K., Menz Hylton B., Taylor, Anne W. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 2008, 1:2doi:10.1186/1757-1146-1-2. Holsheimer J, den Boer JA, Struijk JJ, Rozeboom AR. MR assessment of the normal position of the spinal cord in the spinal canal. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15(5):951-959 Mironer E, Bernstein C, Ghodsi A, et al. Evidence for long-term efficacy of SCS in patients with FBSS or CRPS I or II. Poster presented at: North American Neuromodulation Society; December 3-6, 2009; Las Vegas, Nevada. Nicosia, Mareesa. Chronic pain sufferers hit hard by the spiraling economy. The Saratogian. May 3, 2009. Available at: http://www.saratogian.com/articles/2009/05/03/news/doc49fd09f938b25829273434.prt. Accessed on January 11, 2010. North RB, Kidd DH, Farrokhi F,Piantadosi SA. Spinal Cord Stimulation versus Repeated Lumbosacral Spine Surgery for Chronic Pain: a Randomized Controlled Trial in Patients with Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. Pain. 2007;132:179-188. Pain Management. Drug War Facts. Available at: http://www.drugwarfacts.org/cms/node/59. Accessed on: January 11, 2009. Pain Surveys. American Pain Foundation. Available at: http://www.painfoundation.org/newsroom/reporterresources/pain-surveys.html. Accessed on: January 11, 2009. Peter D. Hart Research Associates. Americans talk about pain: a survey among adults nationwide. August 2003. Available at: http://www.researchamerica.org/uploads/poll2003pain.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2010. References Taylor RS, Van Buyten JP, Buchser E. Spinal Cord Stimulation for Chronic Back and Leg Pain and Failed Back Surgery Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Analysis of Prognostic Factors. Spine. 2005;30:152-160. Van Buyten JP,Van Zundert J,Vueghs P, Vanduffel L. Efficacy of Spinal Cord Stimulation : 10 Years of Experience in a Pain Centre in Belgium. Eur J Pain. 2001;5:299-307. Zeigler, Dan MD Treatment of Diabetic Neuropathy and Neuropathic Pain. Diabetes Care. Feb 2008;Volume 31, Supplement 2, pg S255. THANK YOU FOR YOUR TIME The End Questions? 54