GEOG 340: Day 12

advertisement

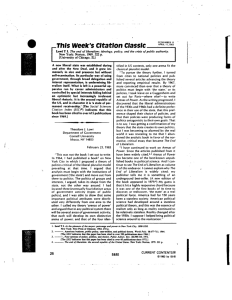

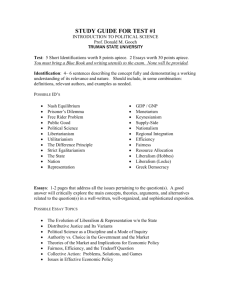

GEOG 340: DAY 12 1 Chapters 10 & 11 HOUSEKEEPING ITEMS Based on feedback from you, here’s what I propose for the mid-term and associated weightings: keep attendance & participation at 10%, make the presentation on the reading worth 15%, make the neighbourhood filtration/ change exercise worth 15%, while the major project and the final would remain 35 and 25% respectively. For those who have already done the presentation, we could take that mark and the neighbourhood exercise and average them. We have Natasha presenting today, as she was unable to present on Tuesday. I got ahead of myself and was presenting on Chapter 11 when we were just starting Chapter 10, so I will touch on any bits that Diego didn’t address from 10 and then finish up Chapter 11. Just a reminder that the neighbourhood filtering/ change assignments are due on Tuesday the 15th. 2 ON THE HOUSING FRONT… 3 CHAPTER 10: THE HIGHLIGHTS The book talks, assuming a U.S. Context, about five distinct periods of urban governance: Laissez-faire and economic liberalism (1790-1840) Municipal socialism and the rise of machine politics (1840-1875) Boosterism and the politics of reform (1875-1920) Egalitatarian liberalism and metropolitan fragmentation (1920-1945) Cities as growth machines and service providers (1945-1973) o In the first period, free enterprise tended to dominate, government was weak (and corrupt), and the lower classes tried to wrest some power from the economic elites. 4 CHAPTER 10: THE HIGHLIGHTS The role of municipalities was limited to a few basic functions and, in Canada – even more than in the U.S. – municipalities were subordinate to higher levels of government, in this case the provinces. Initially, they had very limited access to revenue, but this changed once they started to incorporate (see Figure 10.3). In the second stage, municipalities took a more aggressive and expanded approach to the numerous urban problems as the working classes developed more clout (mostly in regions with a strong industrial base). Dubbed ‘municipal socialism,’ this involved providing essential infrastructural services, including even soft services such as libraries. However, political “machines” also emerged, some of which lasted well into the 1960s. 5 TWO CORRUPT MACHINE POLITICIANS 6 STAGE 3: BOOSTERISM AND REFORMISM Under the cover of reform of corruption and the ‘moral decline’ attributed to increased immigrant populations, the middle and upper-class Ango Saxon elites sought to wrest back control, and to make economic interests predominate. There were also campaigns against gambling, prostitution, and dissolute behaviour (often seen as aided and abetted by alcohol) and for better housing. Women, in particular, led the temperance movement that eventually led to Prohibition from 1920 to 1933. This led to active bootlegging and rum-running industries, including from Canada. 7 Province/Territory Provincial Prohibition Enacted Repealed British Columbia 1917 1921 Alberta 1916 1924 Saskatchewan 1917 1925 Manitoba 1916 1921 Ontario 1916 1924 Quebec 1919 1919 1856 1856 1917 1927 Nova Scotia 1921 1929 PEI 1901 1948 Yukon 1918 1920 Newfoundland (not part of Canada until 1949) 1917 1924 New Brunswick Source: Wikipedia 8 THE EMERGENCE OF URBAN EXPERTS Cities began to require the services of more specialists – accountants, engineers, planners, and architects. There were attempts to de-politicize urban governance and to apply the principles of scientific management. Especially, with the inauguration of streetcar systems, annexations proceeded apace. Original boundaries of Chicago 9 THE FOURTH PERIOD: LIBERALISM AND FRAGMENTATION The fourth period was that of Fordism in housing (or at least the start of it) and in the production of automobiles. Suburbanites began to resist annexation, preferring to remain independent of the big city. The loss of much of the middle class weakened the tax base and economic viability of the core cities, while migration from overseas and down South placed an ever-greater burden on their resources (see Figure 10.7). The Euclid decision of the Supreme Court in 1926 gave municipalities the power to zone land uses. In Canada, provinces delegate that power to municipalities. 10 THE FOURTH AND FIFTH PERIODS: LIBERALISM AND FRAGMENTATION/ GROWTH MACHINES, ETC. The New Deal partly arose from the stronger political urban constituency and heralded a new alliance between blue collar workers and liberal reformers. After the war, the phenomenon known as the “growth machine” emerged that was preoccupied with growth and development at all costs. With apologies to Eisenhower, I have called it the “residential-industrial” or “commercial-industrial complex,” denoting the alliance between developers, local politicians, and the business community in an ‘old boys’ club.’ Nanaimo for decades has been a textbook case. 11 THE FOURTH AND FIFTH PERIODS: LIBERALISM AND FRAGMENTATION/ GROWTH MACHINES, ETC. Figure 10.8 indicates some of the constituencies involved. By the 1960s, more and more groups were dissatisfied with the results of growth machine politics – victims of freeways and of urban renewal, those outraged by the destruction of heritage icons like Penn Station, the civil rights and Black Power movements (and similar movements among Hispanics). o Inspired by the ideas of Jane Jacobs and others, new urban social movements emerged which challenged the status quo. 12 THE FOURTH AND FIFTH PERIODS: LIBERALISM AND FRAGMENTATION/ GROWTH MACHINES, ETC. A downside of this was that it wasn’t only the oppressed who became newly empowered. So too did the relatively privileged and they learned how to influence the political process as well, as manifested in so-called NIMBY and BANANA movements. Discussion question: people who might be characterized as NIMBYs are often reacting against insensitive, lousy development in the past, and a lack of genuine consultation and involvement. But at the same time, from a sustainability point of view, keeping the status quo exactly as it is is not a viable option. So: how to be sensitive to democracy and to take into account the need for new, more dense urban forms and other potentially unpopular measures, such as mixed income housing, mixed use, and restrictions on the automobile? 13 THE SIXTH PHASE: ENTREPRENEURIAL POLITICS AND NEO-LIBERALISM Beginning in the early-to-mid 70s, governments at all levels began experiencing what has been called “the fiscal crisis of the state.” New York City nearly went broke, for instance. Public infrastructure declined and people began to spend more time creating their own private paradises of home entertainment systems, private security systems, and private schools for their children. Moreover, gated communities and suburbs that could opt out of the financial problems of the central city were only too happy to do so. Detroit is a poster child for the fiscal crisis described on p. 247. With a decline in senior government funding, governments, municipalities were forced to rely on public-private partnerships, and on fees and taxes from developers. 14 THE SIXTH PHASE: ENTREPRENEURIAL POLITICS AND NEO-LIBERALISM As middle class incomes stagnated, it became a hard sell to raise property taxes, and the middle class was increasingly open to the siren song of neo-liberalism that blamed social problems on so-called “freeloaders.” So-called “taxpayers’ revolts” forced massive cuts in local services and in the number of municipal employees. In recent years, states have voted in legislation that allows them to break the backs of the public employee unions. Many public services were also privatized, less so in Canada. Especially, in the U.S., one also saw the emergence of “privatopias” – master-planned communities that homogeneous, exclusive, and controlled down to the tiniest detail. 15 THE SIXTH PHASE: ENTREPRENEURIAL POLITICS AND NEO-LIBERALISM The rest of the chapter reviews a host of issues – the fact that homeowners tend to be conservative because their house is their biggest financial asset, that there is often conflict over new housing styles (‘McMansions’) being inserted into more traditional neighbourhoods, that many reasonably well-paid people like nurses and firefighters can’t afford to live in the cities where they work, & the emergence of Smart Growth as an alternative to either no growth or sprawl. 16 THE SIXTH PHASE: ENTREPRENEURIAL POLITICS AND NEO-LIBERALISM We’ve also seen a tendency to remove ‘undesirables,’ such as homeless people from city streets and parks, and the efforts of cities to sell themselves to investors through offers of city-owned land, tax relief, and major amenity provision. Again, Nanaimo provides some interesting examples of this. This is part of a large effort at ‘re-branding.’ As we’ve discussed before, middleclass professionals have rediscovered the advantages of urban living. At the end of the chapter, the authors offer three models of urban power: elitism, pluralism, and hyperpluralism. Which one do you think best fits the reality of Nanaimo? 17 REMAINDER OF CHAPTER 11 Many innovative, if not very successful, urban programs were initiated in the U.S. in the heady ‘60s, such as Economic Opportunity Act, Head Start, and Model Cities, along with funding for transit. Also, in 1970, there was the start of environmental legislation (National Environmental Protection Act). Enormous growth in the planning profession, in planning schools, and in the profession’s esprit de corps. The first planning school in Canada was established at UBC in 1951 by Peter Oberlander, now deceased. His wife, still practicing in her ‘80s, is one of Canada’s leading landscape architects. 18 THE ETHOS OF THE AGE The book expresses it well: “There was an evangelical spirit to the whole profession. Cities should be better places. They could be…. Equipped with the latest developments in social science… – behavioral theory, regional economics, regional science, quantitative geography, systems analysis, and transportation modeling – the stage was set for a golden age of planning on a truly heroic scale. Cities everywhere were recast through strategic plans based on the modernizing principles of strict separation of land uses, slum clearance, large scale civic and commercial renewal projects, urban expressways and, in Europe, new towns and public housing schemes. “Too often, though, the result was a complex of slab-like buildings and parking structures, often in the Brutalist style of reinforced concrete, with pedestrians separated from traffic on elevated walkways and windswept flights of stairways…. [I]n her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities…. [Jane Jacobs] argued that….[l]eft to planners…city landscapes ‘…will be spacious, parklike, and uncrowded…. They will be clean, impressive, and monumental. They will have all the attributes of a well-kept, dignified cemetery.’” 19 NEO-LIBERALISM By the mid-to-late ‘70s, the notion that governments could do anything to assist cities in a positive way that had been abandoned and, under Reagan, federal funding for cities was slashed; everything was to be left to the free market. Another challenge was the property rights movement, whereby property owners took governments to court for exercising their regulatory powers over private lands. This was never a big movement in Canada. This was also the period that saw major redevelopment of industrial and working-class neighbourhoods such as the London Docklands and Battery Park in New York. 20 Docklands and Battery Park 21 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS In recent years planners have begin to abandon the dogma of single use in favour of mixed-use development. This has tied in with the healthy cities movement, which argues that mixed uses and pedestrian-friendly environments make for healthier residents and reduced health care costs. Some jurisdictions, especially in Europe, have created sustainable precincts and neighbourhoods, such as Vauban in Freiberg that minimize car use and are kid-friendly, cooperate, and with abundant public space (see http://www.eltis.org/index.php?ID1=7&id=61&video_id=111). They have also, along with politicians – in some jurisdictions – tried to overcome dysfunctional regionalism by practicing revenue-sharing within regional units, as in Minneapolis-St. Paul. A big issue, more generally, is how to balance local municipal autonomy with rational regional development. In my own view, BC’s system of regional districts is too weak. 22