PPT

advertisement

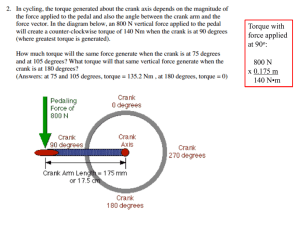

From Kinematics to Arm Control a) Calibrating the Kinematics Model b) Arm Motion Selection c) Motor Torque Calculations for a Planetary Robot Arm CS36510 1 a) Calibrating the Kinematics Model • Resolution, Repeatability and Accuracy • Causes of Mechanical Error • Calibrating the kinematics model CS36510 2 Resolution, Repeatability and Accuracy 1. Resolution: smallest incremental move that a robot can physically produce. 2. Repeatability: a measure of the robot’s ability to move back to the same position and orientation over and over again. Also referred to as ‘precision’. 3. Accuracy: the ability of the robot to move precisely to a desired position in 3D space CS36510 3 Repeatability (Precision) and Accuracy Poor Accuracy Poor Repeatability (Assuming Gaussian Distribution) CS36510 Poor Accuracy Good Repeatability Good Accuracy Poor Repeatability Good Accuracy Good Repeatability 4 Causes of Mechanical Error Denavit-Hartenberg (D-H) Parameters: Link Length (d); Link Offset (a); Link Twist (α); Link Rotation (θ) CS36510 5 Calibrating the Beagle 2 Arm Typical Vicon measurement setup CS36510 Beagle 2 FM Arm with Vicon Markers 6 Oxford Metrics Vicon System ‘Object’definition in Vicon system CS36510 7 Calibrating the ARM Kinematics Model The simulated (perfect) arm is moved to a number of positions using the arm IK model. The end position for each simulated Vicon marker is measured. The real arm is then commanded to the same number of predefined positions in Cartesian space using the joint values calculated from the arm IK model. The actual end position for each real Vicon marker is measured. The real and simulated Vicon marker positions are compared and joint offsets (corrections) are calculated for the simulated arm’s IK model using a least-squares fitting method. The result is that the simulated arm with the corrected IK model produces identical With positioning results as the real arm. i.e. The IK Model simulated arm behaves as per the real arm. CS36510 IK model corrections 8 b) Arm Motion Selection • Joint-by-Joint Motion (JJM) • Slew Motion (SM) • Joint Interpolated Motion (JIM) CS36510 9 Joint-by-Joint Motion (JJM or JBJ) • Strengths: Simplest of the possible motion types; good for un-stowing and stowing an arm as the major joints can be moved one after another. Typically no straight-line trajectory inverse kinematics solution will exist for this type activity anyway. Good at minimising power usage per unit time. • Weaknesses: Joints cannot move simultaneously, hence cannot be used for straight line (continuous) trajectories. Rather payload motion will be in an series of arcs. Large total time to complete all joint motions. CS36510 10 Slew Motion (SM) • Strengths: Also known as “Simultaneous Full Speed” (SFS) motion. All joints that require motion start simultaneously at default joint speeds (usually maximum speed). Quicker joint motion completion when compared to JJM. SM can be used for payload straight-line trajectories. • Weaknesses: Greater power usage per unit time compared to JJM. Joints with smaller angular movement complete their motions before those joints with larger angular movements. Smooth straight-line trajectories not possible. Payload motion tends to zig-zag about the desired straight-line trajectory. CS36510 11 Joint Interpolated Motion (JIM) • Strengths: All joints that require movement start simultaneously and stop simultaneously. Robot attempts to achieve simultaneous start and stop by setting the speed of each joint angular motion to be proportional to the angular distance to be travelled for each joint. Produces smooth straight-line trajectory motion. • Weaknesses: Greater power usage per unit time compared to JJM. Greater computational overheads when compared to SM. CS36510 12 Knot Points • • Straight-line trajectory requires knot points (from spline mathematics) to be generated between the start and finish positions. The desired straight-line between the payload start and finish positions can be uniformly divided into intermediate points in Cartesian space (called knot points)1. Each of these points can be put through the IK model to generate the joint angles required to move the arm to each of these intermediate points in turn; whilst setting each joint speed (e.g. proportional for JIM) to the required angular motion. 1 Taylor, R. H., Planning and Execution of Straight Line Manipulator Trajectories, IBM J. RES. DEVELOP, VOL. 23, NO. 4, pp. 424-436, JULY 1979. CS36510 Start position Knot point Finish position 13 c) Motor Torque Calculations for a Planetary Robot Arm • What is torque, and why do we need it? – Torque (τ) is defined as a turning (or twisting) force – A robot arm joint motor, with an attached linkage and payload, has to generate a torque to be able to move the linkage and payload – The magnitude of τ depends upon the payload force, and the length of the joint motor linkage CS36510 14 Torque Equation - 1 τ=F×l where τ is the magnitude of the torque (N·m), l (in meters) is the linkage length, and F (in Newtons) is the magnitude of the force. In the vertical plane, the force acting upon an object (causing it to fall) is the acceleration due to gravity (for Earth, g ≈ 9.81 m/sec2). Therefore F = m × g, where m is the magnitude of the mass of the object (in kg), and F is normally referred to as the object’s weight. CS36510 15 Torque Equation - 2 sin 90° = 1 sin 45° = 0.7 sin 0° = 0 τ = F × l × sinθ F F L Linkage (length l) Joint Motor F θ = 45⁰ θ = 90⁰ L τ is maximum CS36510 θ = 0⁰ Pivot Point L maximum > τ > zero L τ is zero 16 Real Arm Linkage Torque Joint Motor F L Pivot Point Weight Motor Weight Linkage WM WL L CS36510 (Use maximum (holding) torque case) Real motors and linkages have mass and therefore weight under gravity Assume linkage mass is evenly distributed and the weight is located at the centre of the linkage length 17 Arm Joint Motor Torque Calculations WP WM1 WL1 WM2 WL2 WL3 Payload M1 L1 M3 M2 L2 L3 τM1= (WP × L1) + (WL1 × (0.5 × L1)) τM2= (WP × (L1 + L2)) + (WL1 × ((0.5 × L1) + L2)) + (WM1 × L2) + (WL2 × (0.5 × L2)) τM3= (WP × (L1 + L2 + L3)) + (WL1 × ((0.5 × L1) + L2 +L3)) + (WM1 × (L2 + L3)) + (WL2 × ((0.5 × L2) + L3)) + (WM2 × L3) + (WL3 × (0.5 × L3)) CS36510 18 Motor Torque Calculation Example Based upon arm configuration shown in the previous slide, calculate the three motor torques, i.e. τM1, τM2, and τM3, using the parameters in the table below: CS36510 Titan gravity 1.373 m/sec2 Payload mass 2.0 kg Linkage L1 length 0.3 m Linkage L2 length 0.5 m Linkage L3 length 0.6 m Mass of Linkage L1 0.5 kg Mass of Linkage L2 0.8 kg Mass of Linkage L3 0.9 kg Mass of Joint Motor 1 0.45 kg Mass of Joint Motor 2 0.75 kg τM1 = 0.927 Nm τM2 = 3.226 Nm τM3 = 7.340 Nm 19 Gear Box Selection: a) A gear box will be needed to achieved desired output motor torque b) Gear Box Torque Ratio is ratio of output torque to input torque, e.g. 100:1, 1000:1 etc. c) E.g. for τM3 select 73.1 × 10-3 Nm × 100:1 = 7.31 Nm CS36510 20 Final Points • Maximum holding torques calculated for each motor. Would need to add contingency (e.g. 20%) for each motor. • Calibration, motion selection, and motor torques also apply to a rover locomotion chassis, i.e. steering and drive mechanism • Same techniques can be applied, but chassis details not covered here CS36510 21