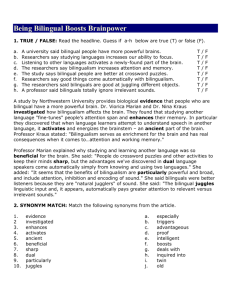

lecture - Linguistics and English Language

advertisement

THE BILINGUAL MIND Antonella Sorace 7 December 2004 Outline • How successful can you be if you start learning a second language as an adult? • What are the differences between “early” bilingualism in childhood and “late” bilingualism in adulthood? • What happens to your first language after you have been speaking a second language for many years? • Is the bilingual brain different from the monolingual brain? • Do data from second language speakers help to understand how language in general works? An interdisciplinary enterprise LINGUISTICS RESEARCH ON THE BILINGUAL MIND COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY How successful can you be if you start learning a second language as an adult? A “critical period” for language? • In many animal species, failure to learn various skills before a certain age makes it difficult or even impossible to learn those skills later. E.g.: • In ducklings: ability to identify and follow the mother • In kittens: ability to perceive visual images. • In sparrows: ability to learn the father’s song. Early exposure to language is necessary • Children raised in conditions of extreme isolation and deprivation do not develop normal grammatical abilities. • Deaf children of hearing parents who are diagnosed as deaf when they are 2 or 3 are impaired in their development of sign language. Why a critical period for language? • A biological mechanism innately geared to the acquisition of language in our species. • Evolutionary advantages of having the mechanism early in life. But what about SECOND language? • Does this mean that second language learning is compromised even if first language development was normal? • Does the fact of already knowing a language help? FIRST LANGUAGE TRANSFERABLE SKILLS? SECOND LANGUAGE Near-native speakers • Speakers who started learning a second language as adults and reached an exceptional level of ability in it. • They would be off the scale in the IELTS band of English proficiency. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Non-user Intermi ttent u ser Extremely limited us er Limited us er Modest user Competent u ser Good user Very good us er Expert user 10 NEAR-NATIVE Subject pronouns in Italian • Subject pronouns can be omitted when they refer to an entity that is clear in context: Maria non c’è, è andata a casa “Maria isn’t here, she went home” • They cannot be omitted in other cases, for example when two entities are contrasted to one another: Maria e Yuri non si capiscono: lei parla l’italiano, lui no. “Maria and Yuri don’t understand each other: she speaks Italian, he doesn’t”. Two kinds of knowledge GRAMMAR OF ITALIAN OMISSION OF SUBJECTS PRONOUNS POSSIBLE INTERFAC E CONDITIONS AM I TALKING ABOUT A KNOWN ENTITY? AM I MAKING A CONTRAST BETWEEN TWO ENTITIES? …….. MEANING IN CONTEXT OMIT SUBJECT DO NOT OMIT SUBJECT Near-native speakers’ errors • Near-native speakers of Italian and Spanish may say: Maria non c’è, LEI è andata a casa. Maria isn’t here, she went home. • Is this due to interference from English? Can’t be (only) interference from English • English and Spanish non-native speakers of Italian make the same mistake. • They know that in Italian subject pronouns can be omitted; they know what the contextual conditions are. • In most cases, they use subject pronouns correctly. It could be a coordination problem C OO RD INA TIO N FAI LU RE GRAMMAR OF ITALIAN INTERFAC E CONDITIONS MEANING IN CONTEXT Another interface problem in near-native speakers • The difference between the sounds /i/ and /I/: SHEEP - SHIP CHEAP - CHIP SEEK - SICK BEAT - BIT DEEP - DIP Etc. The near-native speaker’s dilemma NATIVE -LIKE PHONETIC ABILITY T O DISTINGUISH AND PRONOUNCE PAIRS OF SOUNDS THAT DO NOT CONTRAST IN THE NATIVE L ANGUAGE DIFFICULTY IN CONSTRUCTING PHONOLOGICAL REPRESENTATIONS OF THESE CONTRASTS The ‘snickers vs. sneakers’ problem THIS….. QuickTime™ and a TIFF (LZW) decompressor are needed to see this picture. OR THIS? QuickTime™ and a TIFF (LZW) decompress or are needed to s ee this pic ture. More on interfaces: auxiliary verbs in Italian • ESSERE ‘be’ and AVERE ‘have’. Maria ha lavorato. Maria è partita. ‘Maria has worked’ ‘Maria has left’ • Same distinction as ETRE vs AVOIR in French: Marie a travaillé. Marie est partie. • In early modern English: Christ is risen. The Lord is come. In Italian as a second language… • Auxiliary ESSERE with verbs such as arrivare ‘arrive’, venire ‘come’, partire ‘leave’ ------> ACQUIRED EARLY. • Auxiliary ESSERE with verbs such as rimanere ‘stay’, bastare ‘suffice’, piacere ‘like’-------> ACQUIRED MUCH LATER OR NOT ACQUIRED AT ALL, NOT EVEN AT THE NEAR-NATIVE LEVEL. Native speakers have gradient intuitions • Native speakers of Italian, French, German and Dutch STRONGLY AGREE on the fact that (the equivalents of) verbs such as arrive, leave, come select (the equivalents of) BE. • They DISAGREE, or are UNCERTAIN, on like, stay, exist: sometimes they like them with BE, sometimes with HAVE. The Auxiliary Selection Hierarchy • The choice of auxiliaries is conditioned not only by the grammar, but also by the semantic type of verb. CHANGE OF LOCATION (arrive, come leave, etc.) EXISTENCE OF STATE (like, stay, be sufficient, etc.) HUMAN ACTIVITY (work, talk, play, etc.) ‘BE' 'HAVE' Another problematic interface AUXILIARY SELECTION HIERARC HY AUXILIARIES ESSERE / AVERE INTERFAC E CONDITIONS MEANING OF VERBS A methodological spin-off: how to detect gradience • If developmental data are gradient, we need a method that can detect gradience. • Magnitude estimation, a method borrowed from psychophysics, allows researchers to capture fine ‘shades of gray’ in judgments of linguistic acceptability. • See http://www.webexp.info for a webbased application of Magnitude Estimation developed by Frank Kellet and Martin Corley. The story so far • Many properties of grammar can be successfully acquired in a second language, but properties that involve interfaces between different aspects of language may remain non-native even at the highest level of attainment. What happens to your first language after you have been speaking a second language for a long time? Effects of the second language on the first language FIRST LANGUAGE SECOND LANGUAGE “ATTRITION” STAGE 0 INDIVIDUAL SPEAKER GOES TO LIVE IN A FOREIGN COUNTRY STAGE 1 INDIVIDUAL SPEAKER LIVES ABROAD FOR MANY YEARS AND SPEAKS THE HOST LANGUAGE MORE OFTEN THAN HIS NATIVE LANGUAGE. NEXT GENERATION ARE NATIVE SPEAKERS OF THE HOST LANGUAGE; THEY MAY SPEAK OR UNDERSTAND THEIR PARENTS’ LANGUAGE. NEXT GENERATION ARE NATIVE SPEAKERS OF THE HOST LANGUAGE AND DO NOT SPEAK THEIR GRANDPARENTS’ LANGUAGE. STAGE 2 STAGE 3 Ex-native speakers • Speakers experiencing attrition in their native language at Stage 1 have problems with constructions that require the integration of different types of knowledge, just like near-native speakers. They also say: Maria non c’è, LEI è andata a casa • Ex-native speakers of Spanish often leave out the preposition a with animate direct objects: Maria vio a mi abuela “Maria saw my grandmother” Maria vio la película. “Maria saw the film”. • This property is also applied inconsistently by advanced non-native speakers of Spanish. “Interface” aspects: last in, first out NOT COMPLETE D ACQUIRED IN SECOND LANGUAGE AC QUISITION GRAMMAR INTERFAC E CONDITIONS MEANING IN CONTEXT FIRST TO GO IN NATIVE LAN GUAGE ATTR ITION • This research programme that compares acquisition and attrition requires the contribution of both LINGUISTICS and EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY. • We have both here in Edinburgh. Some of the questions we are working on in PPLS • Does hearing a language automatically activate (“prime”) the other? • Can bilinguals be induced into producing incorrect word orders in both their languages? • What are the effects of feedback, correction, and explicit knowledge on second language development? The broad view • Research on bilingual processing helps us to understand how human language processing works in general. • Research on bilinguals can inform computational models of natural language processing. Bilingual first language acquisition (“early bilingualsim”) • Bilingual children develop two native languages, so in general reach higher levels of attainment than adult learners. • They do not normally mix their languages (unless they want to!). • How early do they differentiate the two languages they are acquiring? Crossover effects in bilingual children • The ‘dominant’ language influences the ‘weaker’ language. • The language with less complex interface conditions influences the language with more complex interface conditions. MORE DEVELOPED “DOMINANT” LANGUAGE “LESS COMPLEX” LANGUAGE LESS DEVELOPED LANGUAGE “MORE COMPLEX” LANGUAGE Effects of input Bilingual children often hear: • Less input (in both languages) than monolingual children. • Non-native input in the minority language. • Input resulting from attrition (usually from the parent who is a native speaker of the minority language). Effects of bilingualism on nonlinguistic tasks • Does the bilingual’s experience of constantly managing two linguistic systems have an effect on coordination in nonlinguistic tasks? “Cognitive control” involves…. • Paying selective attention to the relevant aspects of a problem • Inhibiting attention to irrelevant information • Switching between competing alternatives. • Bialystok, Craik, Klein & Viswanathan (2004): bilinguals are better than monolinguals at tasks involving cognitive control. • The advantages are maintained in older age: bilingualism may help to offset age-related cognitive losses. Future research • Is there a difference between ‘early’ and ‘late’ bilinguals with respect to cognitive control in non-linguistic tasks? • The answer will bring us closer to understanding the relationship between language and other cognitive faculties. The bilingual brain • Structural vs. functional factors: what are the neural substrates of bilinguals’ behaviour? • Does the bilingual brain have a different neural organization from the monolingual brain? • Does the bilingual brain have different neural substrates for the native and second language(s)? QuickTime™ and a TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor are needed to see this picture. Participants • 6 native speakers of Italian who had been screened and categorized as near-native speakers of English. Materials used • NORMAL: The mother was kissing the child. La madre stava baciando il bambino. • SYNTACTICALLY ANOMALOUS: The artist was moulding a clays. L’artista stava modellando il argilla. • SEMANTICALLY ANOMALOUS: The master was teaching the rice. Il maestro stava insegnando al riso. Syntactically incorrect sentences, Italian QuickTime™ and a TIFF (LZW) decompressor are needed to see this picture. Syntactically incorrect sentences, English QuickTime™ and a TIFF (LZW) decompressor are needed to see this picture. Why these differences? • Explanation A: bilinguals need additional resources in the second language to compensate for their inefficient processing abilities. • Explanation B: bilinguals develop additional resources for the second language. Structural scan from Mechelli et al. (2004): higher density of grey matter in left inferior parietal lobe. • Our bilinguals: • Mechelli’s bilinguals: QuickTime™ and a TIFF (LZW) decompressor are needed to see this picture. What do these results tell us? • The structure of the brain can be altered by the experience of acquiring a second language. • The neural substrates of second languages in late bilinguals are different from those of their native language, even if the second language is mastered at near-native levels. What next? • Neural correlates of “interface” conditions on grammatical knowledge. • Work by Hagoort et al. at the Donders Center for Cognitive Neuroscience in Nijmegen is promising. Non-academic implications of research on the cognition of bilingualism • Second language classroom learning and teaching and computer-assisted language learning. • Native language maintenance. • Education of bilingual families. (see http://www.lsadc.org for our leaflet on “Raising bilingual children”). To conclude: The cognitive study of the bilingual mind is an exciting interdisciplinary enterprise. Credits • • • • • • • • • • • • Ellen Bard Adriana Belletti Holly Branigan Michela Cennamo Francesca Filiaci Caroline Heycock Frank Keller Bob Ladd Géraldine Legendre Pim Levelt Martin Meyer Mits Ota • • • • • • • • • • • Martin Pickering Janet Randall Luigi Rizzi Herbert Schriefers Ludovica Serratrice Neil Smith Paul Smolensky Ianthi Tsimpli Nigel Vincent Angeliek van Hout Lydia White Special thanks To my parents To my family: Bob, Marco, and Carlo.