sources of law mindmaps – REVISION

advertisement

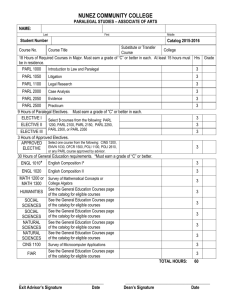

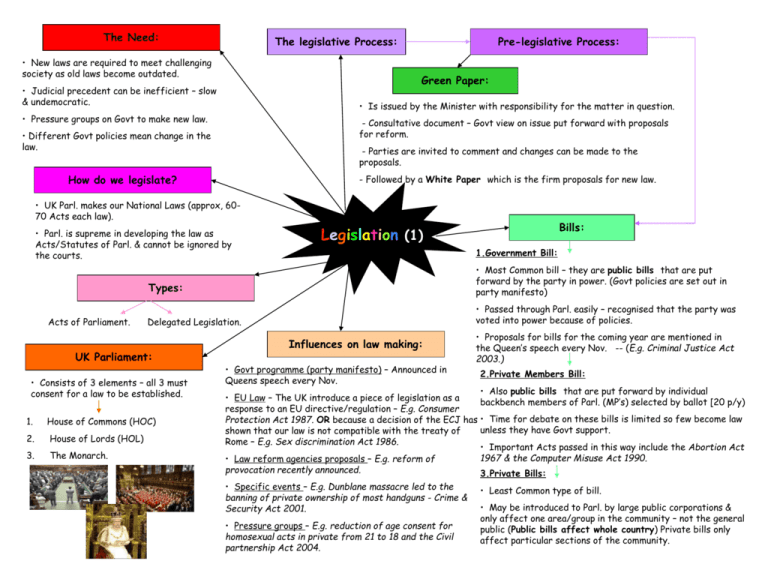

The Need: The legislative Process: • New laws are required to meet challenging society as old laws become outdated. Pre-legislative Process: Green Paper: • Judicial precedent can be inefficient – slow & undemocratic. • Is issued by the Minister with responsibility for the matter in question. • Pressure groups on Govt to make new law. - Consultative document – Govt view on issue put forward with proposals for reform. • Different Govt policies mean change in the law. - Parties are invited to comment and changes can be made to the proposals. How do we legislate? - Followed by a White Paper which is the firm proposals for new law. • UK Parl. makes our National Laws (approx, 6070 Acts each law). • Parl. is supreme in developing the law as Acts/Statutes of Parl. & cannot be ignored by the courts. Acts of Parliament. Bills: Legislation (1) 1.Government Bill: Types: • Most Common bill – they are public bills that are put forward by the party in power. (Govt policies are set out in party manifesto) Delegated Legislation. • Passed through Parl. easily – recognised that the party was voted into power because of policies. UK Parliament: • Consists of 3 elements – all 3 must consent for a law to be established. 1. House of Commons (HOC) 2. House of Lords (HOL) 3. The Monarch. Influences on law making: • Govt programme (party manifesto) – Announced in Queens speech every Nov. • Proposals for bills for the coming year are mentioned in the Queen’s speech every Nov. -- (E.g. Criminal Justice Act 2003.) 2.Private Members Bill: • Also public bills that are put forward by individual • EU Law – The UK introduce a piece of legislation as a backbench members of Parl. (MP’s) selected by ballot [20 p/y) response to an EU directive/regulation – E.g. Consumer Protection Act 1987. OR because a decision of the ECJ has • Time for debate on these bills is limited so few become law unless they have Govt support. shown that our law is not compatible with the treaty of Rome – E.g. Sex discrimination Act 1986. • Important Acts passed in this way include the Abortion Act 1967 & the Computer Misuse Act 1990. • Law reform agencies proposals – E.g. reform of provocation recently announced. 3.Private Bills: • Specific events – E.g. Dunblane massacre led to the banning of private ownership of most handguns - Crime & Security Act 2001. • Pressure groups – E.g. reduction of age consent for homosexual acts in private from 21 to 18 and the Civil partnership Act 2004. • Least Common type of bill. • May be introduced to Parl. by large public corporations & only affect one area/group in the community – not the general public (Public bills affect whole country) Private bills only affect particular sections of the community. *Continuation of Pre-legislative Process* • Bill: once drafted to the approval of Minister(s), is then sent to one of the Houses – usually HOC. First Reading: Green, Winged, Dragons, Fly, Slowly, Clockwise, Round, The, Old, Ruin. The bill is introduced to the HOC – merely notifies the House of the Bill and it’s the subject matter. No debate. • Legislation is sovereign over other forms of law in the ELS. • Can overrule any custom, judicial precedent, delegated legislation or former legislation. • Based on the idea of democratic law making – made by elected Parl. • Are no limits on what Parl. can legislate on and it can also change its own powers. Second Reading: The bill is explained by the Minister and followed by a ‘political’ debate about the principles of the bill, which is then followed by a vote. Parliamentary Supremacy: • Each new Parl. should be free to make or change the law as it wishes – not bound be law made by a previous Parl. Legislation (2) • An Act of Parl. cannot be overruled or challenged by the courts. Committee Stage: This follows the second reading, where the bill is examined inclusive of the subject area – bill is scrutinised and amendments can be made. Third Reading: This coincides with the report stage and makes a final debate about the bill in its amended form. Other House: Any amendments will only be effective if agreed by HOC – major function of HOL is to invite HOC to reconsider. If agreement is not reached bill can be sent for royal assent after a year. Royal Assent: The Monarch gives approval of the bill. Limitations: • Membership of the EU: EU laws take priority over English law even where the English law was passed after the relevant EU law. • Human Rights Act: All Acts of Parl. must be compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. Under S.4 of the HRA the courts have the power to declare an Act incompatible with the HRA. What: • Delegated legislation is a law made by someone other than Parl. but with the authority of Parl. • Authority is usually laid down in a ‘Parent Act’ known as the enabling Act – creates the framework of the law, allowing delegated legislation to make more detailed law in the area. (Control) Enabling Act: (Control) Negative Resolution Procedure: • States the powers of the Minister. – Power to make D.L • Become law unless within 40 days there is an objection & rejected. • Effectiveness: Gives quite broad powers – difficult to deem ultra vires. • Effectiveness: No debate in the 40 days that is laid before Parl. (Control) Affirmative Resolution Procedure: • Must be approved by both houses – specifically approved. • Effectiveness: More control because Parl. have to approve to D.L for it to become law. Then the negative procedure but Parl. can only annul, approve but cannot amend. Why: • Parl. does not have the time to debate every detail of every Act. • Parl. will not always have the necessary expertise to deal with a particular issue. (Control) Super-Affirmative Resolution Procedure: Delegated Legislation • Effectiveness: Even more control as the minister must consult with various people and have regard to what the HOP say/recommend. • Delegated legislation can be changed easily – allows quicker response to changing circumstances. • Parl. can not always respond quick enough in emergencies. (Control) LRRA 2006: • The procedure for makings SI’s – aimed to replace existing law. Types: 1. Statutory Instruments – rules, regulations and orders, issued by ministers, national in effect. 2. By Laws – issued in local authorities, local in effect. 3. Orders in Council – issued by the Privy Council, generally only used in emergencies. 1.Statutory Instruments: • Most Common procedure – introduced by Govt ministers. • Will become law unless rejected by Parl. within 40 days. • Example: Codes of practice under PACE. • Made under Reform Act 2006 – more power. • Effectiveness: Provides additional control where the minister is repealing/amending a law that imposes a burden – Minister must consult interested parties. 2.By Laws: (Control) Negative Resolution Procedure: • Made by local authorities to cover local issues or by public corporations. • Reviews can draw Parl’s attention to problems. • Effectiveness: Can only refer back to Parl. cannot amend. • Involves matters of local concern – passed under the Local Govt Act 1972. • Example: Local parking regulations. 3.Orders in Council: • Introduced by the Queen & the Privy Council – in times of emergency under the emergency powers Act 1920. • Only used in emergency when Parl. is not sitting • Main function: give effect to EU directives. • Example: The misuse of drugs act 1971 (revised 2003) *CONTINUATION* JUDICIAL REVIEW: Advantages: • Solves time – Parl. is only able to pass approx 50 acts. • Flexible – D.L can be passed much quicker if they are not required to go through the official legislation process – changed in time of emergency. • Experts – Local councils are much better equipped to make bylaws concerning their area. Void to Substantive Ultra Vires: • Fire Brigade Union Case 1935 – Only has the power to regulate about the subject been allowed to do so. Disadvantages: Delegated Legislation (2) • Undemocratic – Civil servants make SI’s – undemocratic for such people to have the power to pass D.L Void to Procedural Ultra Vires: • Quantity – D.L is being made by people and organisations outside of Parl. • LRRA 2006 – Cannot repeal without succeeding to consult all relevant bodies before introducing new regulations – Any procedure not followed. • Scrutiny – The quantity makes it difficult for public to be informed about the changes in the law. • Overused – Volume makes it difficult to discover what the present law is. • Mushroom Case. Void due to Unreasonableness: • Example is the case of Strinctland v Hayes. – Prohibiting or regulating a law which is unreasonable. – Things are too widely drawn. • Lack of Control – Parliamentary scrutiny is limited – limitations of judicial review. Effectiveness: 1. • Problems of interpretation – Can be bulky and complex. 2. • For judicial review to happen relies on a individual bringing a claim. • The Enabling Act can be wide and counter wide powers to make D.L. • There a certain barriers to this including money and knowledge that the piece of D.L has gone beyond the power Parl. gave. • Therefore it would be difficult to say that the individual/body has gone beyond the power given to them in the enabling Act. The Need for SI: Mischief Rule: • A broad term – where words are used to cover several possibilities – E.g. Brock v DPP (1993), Dangerous dogs case. • The mischief rule gives judges the most flexibility when deciding what Parl. intended to stop. • Ambiguity – where a word has two or more meanings. • Looks at the gap in the previous law and interprets the words ‘to advance the remedy’. • A drafting error – unnoticed in scrutiny. • Established in Heydon’s case (1564). • As the ditty goes: ‘I’m the parliament draftsman, I compose the country’s laws, and of half the litigation I’m undoubtedly the cause!’ • When using this rule, a judge should consider: • what common law was before the Act was passed. • what the problem was with that law. • New developments – new technology may mean that an old Act of Parl. does not cover present day situations – E.g. Royal college of Nursing v DHSS (1981) • what the remedy was that Parl. was trying to provide. Statutory Interpretation (1) • Changes in language – meanings of words can change over the years – E.g. Cheesman v DDP (1990) • What was the true reason for the remedy. CASES: • Smith v Hughes (1960) Literal v Purposive Approach: • Royal College of Nursing (1981) • The conflict: should judges examine each word and take them literally or should it be accepted that an Act cannot cover every situation and that meanings of the words cannot always be exact. Golden Rule: • Literal – produces absurd results. • The golden rule is an extension of the literal rule – if the literal rule gives an absurd result, which is obviously not what Parl. intended, the judge should alter the words in the statute in order to produce a satisfactory result. • Purposive – goes beyond the powers of the judiciary but is advocated and used in EU law. • Judges may use the narrow approach (choose between different meanings of a word) – Jones v DPP (1962): ‘if they are capable of more than one meaning then you can choose between those meanings, but beyond this you cannot go.’ LORD REID Literal Rule: • The judges take the ordinary and natural meaning of the word and apply it, even if doing so creates an absurd result. • Respects Parliamentary Sovereignty. CASES: • Whitley v Chappell (1868) • OR Judges may use the broad approach (modifying words in the statute to avoid absurdity). • Lord Esher (1892): ‘the court has nothing to do with the question of whether the legislature has committed absurdity.’ • London & NE Railway Co v Berriman (1946) CASES: • Fisher v Bell (1961) • R v Allen (1872) • Michael Zander: ‘mechanical and divorced from the realities of the use of language. • R v Harris (1836) • Re Sigsworth (1935 Purposive Approach: • Looks at the intentions/purposes behind the passing of an Act – seeks to interpret the words of the statute to give effect to Parl’s intention. Intrinsic & Extrinsic Aids: • Examples include: • In order to determine the meaning of a section of an Act of Parl. the judge may wish to look at other sections in the Act: • definition section • long/short title • Preamble (purpose of the act) • R v Registrar General ex Parte Smith (1990) – when considering s.51 of the Adoption Act 1976 the court applied the purposive approach to prevent a convicted murderer from being able to discover his natural mothers identity because Parl. could not have intended to promote serious crime. This was despite the fact that he had made the application in the correct manner and was prepared to see a counsellor – Literal view: entitled to the information. • OTHER CASES INCLUDE: • Jones v Tower Boot CO (1977) Statutory Interpretation (2) ADVANTAGES Prevents cases ending in absurdity/injustice (LORD DENNING) DISADVANTAGES Relies on the use of extrinsic aids, especially Hansard which causes delays and adds costs to the case. Allows the court to take account of changes in language (Cheesman) Difficult to find Parl’s intent especially where there have been social and technological changes since Parl. make the law. Allows the court to take account of social and technological advances (Quintavalle) Trying to find intent gives a judge too much power – may be construed as making rather than interpreting law (LORD SCARMAN & LORD SIMMONDS) • Coltman v Bibby Tankers (1987) • Fitzpatrick v Sterling Housing Association. • dictionary • hansard • human rights Act 1998 • legal textbooks • interpretation Act 1978 • explanatory notes. Rules of language: CASES: • R (Quintavalle) v Sec. of State for Health (2003) – HOL used the purposive approach in deciding that organisms created by cell nuclear replacement came with the definition of ‘embryo’ in the Human Embryology and Fertilisation Act 1990 even though CNR was not possible at the time. • previous Acts of Parl. on the same topic • Intrinsic Aids: Sources within the Act. • Lord Denning championed this approach in Magnor & St Mellons v Newport Corporation (1950) he said: ‘we sit here to find out the intention of Parl. & carry it out, and we so this better by filling in the gaps and making sense of the enactment than by opening it up to destructive analysis.’ • Opponents of the same case: Lord Simmonds regarded the approach as a ‘naked usurpation of the legislative function under the thin disguise of interpretation.’ • Extrinsic Aids: Sources outside the Act. Avoids problems with broad terms • Ejustdem Rule: where there is a list of words followed by general words, then the general words are limited to the same kind of items as the specific words. – CASE: Powell v Kempton Park Racecourse (1899) • Expresso Unius Exclusio Alterius: (the mention of one thing excludes others) where there is a list of words which is not followed by general words, then the Act applies only to the items in the list. – CASE: Tempest v Kilner (1846) • Noscuiter a Sociis: (a word is known by the company it keeps) words must be looked at in context and interpreted accordingly, it involves looking at other words in the same sections or others of the Act. – CASE: Inland Revenue v Frere (1965) Presumptions: • Presumption against a change in common law: Common law will apply unless Parl. has expressly altered it and made this clear in the Act (Leach v R) • Presumption that mens rea is required: The basic common law rule is that no-one can be convicted of a crime unless it is shown that they have the intention to commit it. (Sweet v Parsley) • Presumption that the crown is not bound: By any statute unless the statute expressly says no. • Presumption that legislation does not apply retrospectively: This means that no Act of Parl. will apply to past happenings. Each Act normally only applies from the date it comes into effect. Key Functions of the ECJ: LAW MAKING INSITUTIONS: • To ensure that the law is applied uniformly in all MS’s by carrying out 2 functions: 1. Hears cases – to decide whether MS have failed to fulfil obligations under the treaties – E.g. Re Tachographs where the UK failed to implement a regulation on the use of Tachographs in road vehicles for the carriage of goods. EU Parl: Art.234: • Based in Brussels & Strasbourg. • There are 785 members of EU Parl. who are elected by the citizens of the member state (MS) every 5 years. • Main function: to discuss and comment on the proposals put forward by the Commission, but has no direct lawmaking authority. • Assent of Parl. is required to any international agreements the Union wishes to enter in – E.g. admitting new MS. • Has some power over the Union budget. • The court of justice shall have jurisdiction to give preliminary rulings concerning: a) the interpretation of treaties b) the validity and interpretation of acts of the institutions of the Union c) the interpretation of the statutes of bodies established by council, where those statutes so provide. an act of the European Law (1) • 27 commissioners who act independently of national origin. ECJ: • Proposes and presents drafts of legislation to the Council – ‘the commission proposes and the council disposes.’ • Function set out in Art.220 of the Treaty of Rome ‘to ensure that in the • ‘Guardian of the treaties’ – checks that the MS are following interpretation and application of the the laws – has a duty to intervene and refer to ECJ. treaty the law is observed.’ • Responsible for the administration of the Union and has executive powers to implement the Union’s budget. Council of Ministers: • Made up of representatives from each national Govt. who will attend meetings related to their national responsibility. • Principal decision making body. When must a referral be made? • Where there is no appeal from the national court within the national system – E.g. case must be referred from the HOL’s EU Commission: • Initiates all new EU Laws. 2. Preliminary rulings – hears references from national courts for preliminary rulings on points of EU law under Art.234. • Decides cases involving citizens of the MS. • Other courts are allowed to make a reference but do not have to – E.g. the COA does not have to refer questions. • CASE: Torfaren Borough Council v B&Q (1990) • The ECJ make a preliminary ruling and send the case back to the original court for it to apply the ruling to the facts in the case. Discretionary Referrals: • Sits in Luxembourg and has 27 judges 1 from each MS – appointed every 6 Bulmer v Bollinger (1974) COA set out the approach for deciding years. if a discretionary referral should be made: • Full court = 11 judges (also chambers • Guidance on the point of law must be necessary to come to of 5/6) decision in case. • Assisted by 9 Advocates – A-G under • No need to refer a question which has already been decided by • The Council of Ministers is the ‘effective centre of power’. Art.223 will research all legal points the ECJ in previous case. involved and present the case publicly. – the heads of State of the EU countries vote on the • No need to refer question which is clear & free from doubt – proposed laws. The head states have differing amounts of CASE: Van Duyn v Home acte clair. voting power depending on the size of their country (qualified Office (1974) majority voting). • Court must consider all circumstances of case. – refrains whether to refer or not. Sources of EU Law: • EU law is supreme - Van Gend en Loos. • If UK legislation conflicts with EU – UK becomes void. Primary: • Legal action will be taken against a MS who fails to implement EU law – Francovich principle. • Treaties, the most important of which is the Treaty of Rome, and other agreements having similar status. • Primary legislation is agreed by direct negotiation between the government of MS. *READ ADDITIONAL NOTES* Secondary: European Law (2) Treaties: • Agreements laid down in treaties are subject to ratification by the national Parl’s – same for the amendments made to the treaties. • New legal order was set out in Costa v ENEL & Van Gend en Loos. EU Constitution: • The EC Treaty (the Treaty of Rome as amended) can be seen as the basic constitution of the EU Union. • There has been an attempt to have ratified a EU Constitution as we have seen but Holland and France Refused. • Treaty of Lisbon may be the new constitution. • Can refer points of law under Art.234 to the ECJ – when point is unclear *READ ADDITIONAL NOTES* Indirect Effect: • Where a directive has not been implemented by MS or has been inadequately implemented an individual can take action against another state by using ‘indirect effect.’ • Von Colson v Land Nordrhein-Westfahlen Directives & Direct effect: • Where a MS has not implemented a directive within the time laid down the ECJ has developed the concept of ‘direct effect’ • If the MS has not implemented the directive or implemented it in a defective way – it will still be directly enforceable by an individual against the MS. • Founding treaties were the Treaty of Paris 1951 and the Treaty of Rome 1957. • The Treaty of Rome created a ‘new legal order’ – meaning that the body of law was no binding on the institutions of MS and its citizens. • Purposive approach gives the judiciary more power & freedom to interpret legislation. CASES: • Legislation passed by the institutions of the union under Art.234 of the Treaty of Rome. • The Treaty of Rome (originally the EEC treaty) was amended in 1992 by the Treaty of Maastricht and its name was changed to the EC treaty. Benefit of EU Membership: Effect of EU Membership: Vertical & Horizontal direct effect: • ‘Vertical Direct Effect’: The Provision has effect between citizen and state. • ‘Horizontal Direct Effect’: The provision has effect between citizen and citizen. Treaty provisions can produce vertical direct effect if, they are “clear, precise and unconditional” leaving no discretion to MS as to implementation. CASES: • Macarthys Ltd v Smith 1979 • Diocese of Hallam Trustee v Connaughton 1996 • Defrenne v SABENA (no.2) 1976 CASES: • Marshall v Southampton 1986 • Foster v British Gas 1990 Secondary sources: • Regulations – binding in all the MS • Directives – binding but MS may choose method of implementation • Decisions – binding on those MS to whom they are addressed. • Recommendations – not binding • Opinions – not binding • Case Law – binding in all MS What is JP & the concept of Stare Decisis: Stare Decisis – ‘stand by what has been decided and do not unsettle the established’. Supports idea of fairness & provides certainty. Where past decisions of judges creates law for future judges to follow. Higher courts bind lower courts and in some cases themselves. Created by the ratio decidendi & referred to as ‘case law’. Cases which illustrate stare decisis – Knuller v DPP and Jones v Secretary of State for Social Services (where despite regarding an earlier decision as wrong, refused to overrule using the practice statement, preferring certainty) Accurate law reporting is essential for stare decisis to operate. Stare decisis can be avoided by distinguishing, overruling and reversing Types: Persuasive ADVANTAGES DISADVANTAGES Certainty Rigidity Consistency & fairness in the law Complexity Precision Illogical Distinctions Flexibility Slowness of Growth Time saving Ratio Decidendi & Obiter Dicta Ratio Decidendi Principles of law used to decide a case – ‘reason for deciding’. Sir Rupert Cross: ‘any rule expressly or impliedly treated by the judge as a necessary step in reaching his conclusion’. The part of the decision that forms the precedent for future cases to follow. Obiter Dicta The remainder of the judgement. ‘Other things said’. Judge in future cases does not have to follow but may be persuasive (Howe & Gotts) Problems Separating the ratio and obiter More than one speech at the end of the case with different reasons for decisions (ration decidendi) Judicial Precedent Hierarchy of the Courts COURT Types: Binding Types: Original Original If point of law which has never been decided forms new precedent Judge may look at cases which are closest in principle and use similar rules (reasoning by analogy) Here, the judge has a law making role (creating new law). Cases: Hunter and Others v Canary Wharf Ltd and London Docklands Development Corporation (1995) Persuasive Precedent that isn’t binding on the court but the judge may consider it and decide it is the correct principle and is persuaded to follow it. Courts Lower in the Hierarchy: R v R (1991) – the H of L agreed with and followed the same reasoning of the C of A when deciding that a man could be guilty of raping his wife. Decisions of the Privy Council since many of its judges are also members of the H of L’s, their judgements are treated with respect any may often be followed. A-G for Jersey v Holley (2005) (PC) followed in R v James; R v Karimi (2006) by the C of A instead of following a H of L precedent. Statements made Obiter R v Gotts (1992) – CA followed obiter of HL in R v Howe(1987) A dissenting judgement Hedley Byrne v Heller & Partners followed dissenting judgements in Candler v Crane Christmas & Co (1951). Decisions made by courts in other countries: Re A (2000) Conjoined Twins; Re S Refusal of Medical treatment - American precedent Binding Precedent from an earlier case which must be followed even id the judge in the later case doesn’t agree with the legal principle. Only created where facts are sufficiently similar and when decision was made by a court which is senior to (or in some cases the same level). COURTS BOUND BY IT COURTS IT MUST FOLLOW ECJ All courts None HL All courts in the ELS ECJ CA Itself (with some exceptions) DC & all other lower courts ECJ & HL DC Itself (with some exceptions); HC & all other lower courts ECJ, HL, CA HC County Court; Mags ECJ; HL; CA; DC CC Possibly Mags All Higher Courts MC None All Higher Courts Avoiding Precedent: Overruling & Reversing Overruling: The court in a later case states that the legal rule in an earlier case is wrong. It may happen when: - A higher court overrules a decision made in an earlier case by a lower court - The ECJ overrules a past decision it has made - The HL’s use the practice statement to overrule a past decision of its own. Pepper v Hart (1993) overruling Davis v Johnson (1979) Reversing: A court higher up the hierarchy overturns the decision of a lower court on appeal in the same case. E.g. the CA disagrees with a ruling of the high court/crown court and reverses their decision by coming to a different view of the law. The Privy Council & Precedent The Privy Council & Precedent Decisions not usually binding but form persuasive precedent. Usually follow decisions of the HL except where the point of law has developed differently in the country from which the appeal has come. Unusual case = A-G for Jersey v Holley – PC refused to follow HL’s decision in Smith (Morgan James). CA in ELS then followed Holley rather than Smith because the decision was made by 6 law lords. CA is bound by the HL and ECJ. Can depart from HL decision in human rights cases where it is different from the decisions of the ECHR Lord Denning: an avid champion of the view that the CA should not be bound by the decisions of the HL. ( Broome v Cassell & Co Ltd (1971) LD refused to follow the HL in Rookes v Barnard (1964) Schorsch Meier GmbH v Henning (1975) and Miliangos v George Frank (Textiles) Ltd (1976) the CA refused to follow HL in Havana Railways (1961) which said that damages could only be awarded in sterling. On appeal to the Lords they pointed out that the CA had no right to ignore overrule decisions of the HL. However the HL then went on to use the Practice Statement to overrule its own decision agreeing with the reasoning of Lord Denning. Avoiding Precedent: Distinguishing Distinguishing: The judge finds that the material facts of the case are sufficiently different for him to make a distinction between the case he/she is hearing and the past one. – He is then not bound to follow it. Balfour v Balfour (1919) & Merritt v Merrit (1971) Judicial Precedent (2) CA bound by HLs Court of Appeal & It’s OWN precedent: CA & Its own decisions One division of the CA will not bind the other Within each division, decisions are normally binding. Young v Bristol Aeroplane Co Ltd (1944) – although there are limited exceptions. conflicting decisions in past CA cases - can choose a decision of the HL which effectively overrules a CA decision - CA must follow the decision of the HL decision was made per incuriam Denning tried to challenge the rule in Young’s case but in Davis v Johnson the court “expressly, unequivocally and unanimously reaffirmed the rule in Young”. Justifications: there would be a risk of confusion and doubt if the CA was not obliged to follow its own past decisions. Although the HL’s needs power to review as it is the last court of appeal, the CA does not as their errors can be corrected by the HL’s. Per incurium case examples: Williams v awcett (1986); Rickard v Rickard (1989) ‘rare and exceptional cases’ that the CA would be justified in refusing to follow a previous decision. Criminal Division Can also refuse to follow a past decision if the law has been ‘misapplied or misunderstood’. because people’s liberty is at stake, R v Spencer (1985) Reasons for CA being able to depart from HL Reasons Against CA being able to depart from HL •Cases could be decided on their own merits making judgments more equitable; •The law would potentially move more with changing social conditions; •It would be quicker to change incorrect decisions; •It would make the law less rigid; •Avoids costly and lengthy appeals to update the law to the HL’s •Very few cases reach the HL’s •It would make the law less certain as CA could overrule HLs; •It would make advice given by lawyers less precise; •It may cause an increase in litigation; •Courts would be confused over which precedent to follow.